Do you ever let the death of a patient get to you? In this Focus piece, one cancer surgeon talks about his own experience and argues that shutting down your emotional responses is neither feasible nor desirable.

This article was first published in The Oncologist vol. 18 no.2, and is republished with permission.

© 2013 AlphaMed Press. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0289

As physicians, we are trained to expect loss. Every disease has the ability to develop, to progress, and ultimately to cause a patient to succumb. We protect ourselves from the pain of such an experience by steeling ourselves from the self-condemnation that accompanies wondering, “What more could I have done?” We are rarely able, however, to ever completely absolve ourselves.

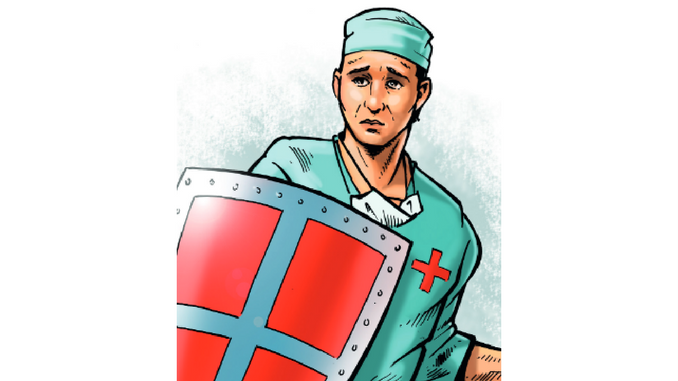

We protect ourselves behind the armour of our white coats

As surgeons, we are fortified to deal with such events. We are invincible. We invade a body and put it back together. We are supermen. We make hundreds of critical, life-altering decisions before most people have had their morning coffee. Each of our decisions affects a patient’s life, both the quality and quantity. But how many are correct? Just one error, one poorly placed suture, one inaccurate assumption can result in disaster.

Just as disastrous is not feeling responsible or guilty after a complication or death. Our guilt, although perhaps self-indulgent, is redolent of our humanity. We employ every means to protect ourselves: defiance, arrogance, logic, and rationalisation – an alphabet of protective shields. Humour is a common mechanism for coping. However, the jokes are never particularly funny and are far from comforting.

We take classes to educate us in the stages of grief. We recognise the importance of the process for our patients and their families: the anger, the denial, and finally the acceptance. Although these stages are acceptable for others, we as physicians strive to remain stoic. By taking our feelings out of the equation, we somehow feel we are better able to help patients and their families through the ultimate emotional event. We effectively step back and isolate ourselves through the use of science and technology, protecting ourselves behind the armour of our white coats. To absorb every bit of grief that we observe during daily rounds would surely make our shoulders sag.

I was asked to see a patient by a colleague leaving for sabbatical. The patient was a vibrant, active, yet self-reflective man deteriorating daily from the effects of a massive pelvic tumour. Despite his wasting body, his eyes shone with his desire to do whatever possible to extend and improve his life. We entertained the idea of chemotherapy or perhaps palliative radiation treatments to buy him some time. In the end, he was simply too ill for either, but something had to be done. He was not ready to palliate.

We spent four weeks organising the surgical team for a heroic operation. It was an all-star team and six of us would operate: urologists, general surgeons, orthopaedists, and vascular surgeons. We spent hours reviewing anatomy, histology, and three-dimensional reconstructions. We developed a game plan, complete with contingencies against unanticipated finding. We sought perspectives from respected consultants and national thought leaders. We had every base covered.

Meanwhile, he spent the four weeks building his strength, maximising his nutritional status, and embracing his family. He spent time in meditation and prayer. His pain largely prevented mobility but could not dampen his spirit. Despite the weight loss, forfeiture of strength, and continually altered body image, he maintained a steely-eyed determination to beat the monster that grew within. He said that he would survive the cancer. He said he was an optimist and that, live or die, he was a winner.

We exhibited the typical surgical audacity that adrenaline fuels following his operation. With acknowledged conceit, we gave each other high-fives following his 10-hour surgery: “Couldn’t have gone better.” “That was a real surgery.” “One in a million.” We had completely removed the 5 lb sarcoma that was causing such pain. He had been bedridden and nauseated. Now, he’d be walking and eating within days. Perhaps our false bravado was emboldened by the knowledge that, although we may have been the victors in the battle, the war was not nearly over.

He spent the holidays at home, but the cancer came back. It was unremitting, vulgar, and obtrusive. We were going backwards. Despite the cancer’s recurrence, his family said that his illness had been an incredible spiritual journey. They were amazed by the outpouring from their community and had never loved or appreciated each other as they did during those intense three months.

He told me that he was not afraid of dying. He believed in an afterlife and that it was a beautiful place. He said that he was “just a bit concerned about the journey to get there.” If we are so hardened that such a loss is not profoundly felt, then we have indeed lost all compassion and with it every connection to humankind.

Despite our training, our medical armour, and our scientific approach to patient care, it is inevitable that some patients will permeate our shield and affect us in profound ways because we, too, are human. When they do, we must also grieve. Although our shoulders may sag if we allow ourselves to experience these emotions, we will rebound stronger and inspired to better care for our next patient.

Today, this wonderful man died. I hate cancer.

Leave a Reply