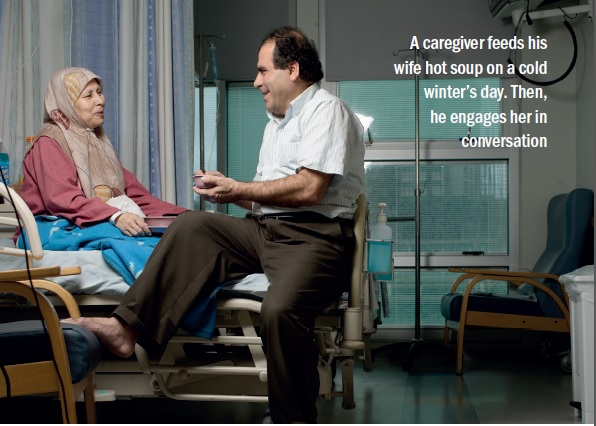

Doctors in Tel Aviv teamed up with a photojournalist to learn more about the role of the unsung heroes who place their patientcompanion at the heart of their world.

This article was first published in The Oncologist vol.18 no.10, and is republished in abridged form with permission. ©2014 Alpha Med Press doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0163

Our Tel Aviv Medical Center, a municipal hospital, is the primary provider of oncologic services to Jewish and Arab residents of both Tel Aviv and Jaffa. Today’s oncology departments host not only patients but also the caregivers who help their patients navigate diagnostic, therapeutic, and ancillary services within the modern cancer care centre. Because caregivers frequently serve as liaisons between patients and healthcare teams,[1] everyone involved benefits when team members understand the caregiving role and value the caregiver’s presence.[2]

What is caregiving?

In the setting of cancer medicine, the “care-giver” is typically an unpaid individual, outside the frame of professional health care workers,[3] who is dedicated to maintaining the well-being of another person, the patient. In the caregiver–patient relationship, the role of caregiver requires attending selflessly to diverse issues associated with malignant disease. Caregivers may provide support on many levels, from emotional and spiritual to cognitive, medical, economic, and legal.

The caregiver’s involvement is dynamic and redefines itself throughout the different phases of the patient’s illness. For example, in early phases, the need to assist in the processing of information is paramount; whereas, in latter phases, concerns typically turn to assessing uncertainty about the future, altered social relationships, and financial issues.[1]

In a supportive role, the caregiver is typically less visible than the patient-protagonist around whom most cancer centres revolve. Caregivers usually develop unique bonds as “companions” to the patients whom they accompany. Prager stated that caregivers rarely receive recognition, and have therefore become the “unsung heroes” of the medical system.[4]

Prager also lists several determinants that might motivate caregivers, such as love, sense of duty, and even feelings of guilt.4 Even when individuals become caregivers reluctantly,[5] the process of caregiving ultimately results in sacrifice, devotion, and commitment. Regardless of the factors that prompt action, caregivers are most often deeply devoted to assisting their patient–companions.

Challenges of caregiving

As more studies focus on the stresses associated with caregiving,[6,7] it is becoming apparent that caregivers not only sacrifice their time and independence but also sometimes their health. A recent report by Rohleder et al. draws attention to the physiologic costs of caring for patients with cancer.6 The report characterises the changes in caregiver neurohormonal profiles (e.g. diurnal output of salivary amylase) and anti-inflammatory signaling (e.g. linear decline in mRNA). Compared with age-appropriate non-caregivers, caregivers are prone to psychological distress, economic hardship as a function of time lost from work, and diminution of health-related quality of life.[8]

In a comprehensive review, Northouse et al. proposed an array of caregiving research questions involving assessment of caregiver preparation, further documentation of care-giver physical and psychological health, and examination of interfaces between caregivers and technologies such as smartphones.[9] The review suggests the construction of a base of evidence to further the understanding of care-giving and its ramifications.

Photodocumentary study

Photodocumentary study

With a goal of contributing to that evidentiary base, we obtained approval from our institutional review board to carry out a photodocumentary study of caregivers within our oncology department setting. Our staff nurses identified patients, with their caregivers, who might be willing to participate in the study. We secured permission not only to take photographs but also to display the photos for public viewing in gallery exhibitions.

An experienced photojournalist captured spontaneous, unposed pictures. To create captions, staff physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and receptionists participated in group discussion. Recognising that the pictures were likely to evoke intense emotional responses, we reassured all captioning-process participants that there were no “correct” responses. The final captions reflect not only reactions to the photo images but also recollections of the original interactions between caregivers and patients. Shown here are samples of the resulting photographs, illustrating several themes characteristic of caregiving.

Each of the exhibit’s caregiver pictures may convey, as the familiar saying goes, “a thousand words” about the special people who, by placing their patient–companions in the centre of their world, commit to doing battle against cancer. We hope that our photos will help to inspire each member of the healthcare team to recognise the importance of the “unsung hero” caregivers who accompany their patients, will encourage caregivers’ support of patients, and will encourage the healthcare team to invite caregivers to participate, as appropriate, in the healthcare decision-making process.

Affiliations:

Benjamin Corn, Ira Dinkevich, Moshe Inbar, Department of Oncology, Tel Aviv Medical Center and the Tel Aviv University School of Medicine, Tel Aviv, Israel; Reli Avraham, Maariv newspaper, Tel Aviv, Israel

Acknowledgement:

Benjamin Corn was supported, in part, by a grant from the Research Fund of the Life’s Door Foundation

References

1. Kim Y, Carver CS. Recognizing the value and needs of the caregiver in oncology. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2012;6:280-288

2. Laizner AM, Yost LM, Barg FK et al. Needs of family caregivers of persons with cancer. A review. Sem Oncol Nurs 1993;9:114-129

3. National Association for Caregiving website. Available at: <zurl>http://www.caregiving.org<zurlx>. Accessed August 27,2013.

4. Prager KM. Alice’s husband. JAMA 2003;289:2333

5. Span P. The reluctant caregiver. New York Times February 20,2013:x

6. Rohleder N, Marin TJ, Ma R et al. Biologic cost of caring for a cancer patient. Dysregulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:2909-2915

7. Schulz R, Beach S. Caregiving as risk factor for mortality. The caregiver health effects study. JAMA 1999;282:2215-2219

8. Van Ryan M, Sanders S, Kahn K et al. Objective burden, resource, and other stressor among informal cancer caregivers. A hidden quality issue? Psycho-Oncol 2011;20:44-52

9. Northouse L, Williams A, Given B et al. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1227-1234

Leave a Reply