For many patients seeking access to treatments unavailable in their home country, the Cross-border Healthcare Directive turned out to be a bit of a disappointment. But a closer look shows it may help raise standards of care in ways that were not widely anticipated.

When Miljana Marković was diagnosed with breast cancer, the news wasn’t all bad. The disease had been detected in time to be safely treated with breast conserving therapy, and this was an option she was keen to go for.

When Miljana Marković was diagnosed with breast cancer, the news wasn’t all bad. The disease had been detected in time to be safely treated with breast conserving therapy, and this was an option she was keen to go for.

But she was worried. Not about the surgery, but about the adjuvant radiotherapy that would be needed afterwards to kill any stray cancer cells that may have been lurking in her breast tissue after the lump had been removed.

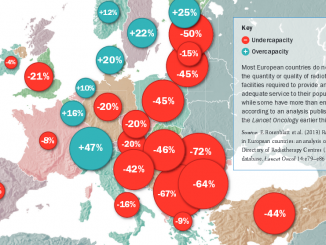

Serbia, her home country, has a quarter of the radiotherapy capacity that it needs. Waiting times are long, machines are old, and frequent breakdowns can bring interruptions to a planned sequence of treatment.

Miljana (not her real name) was married to an oncologist, and knew that delays and interruptions could reduce the effectiveness of treatment. After weighing up her options, she decided to travel to Paris for her course of radio-therapy, paying her own costs for the treatment, travel and accommodation.

Miljana was looking for the treatment that would give her the best chance of the outcome she wanted. But by stepping out of her own health system, and finding her own way to healthcare providers in another country, she became a consumer in the “health/medical tourism” market – where a lack of agreed standards and regulation leaves consumers wide open to exploitation.

The health tourism market

In the public perception, particularly in the West, the sector is dominated by services aimed at healthy, relatively wealthy populations – cosmetic surgery, dentistry, IVF and laser eye treatment – often carried out in exotic locations and increasingly in slightly less exotic locations across eastern and central Europe.

The services are frequently marketed by agencies as a package that bundles together travel and accommodation, an introduction to the medical facilities, translation services, help with the paperwork, and even sometimes sightseeing or shopping trips.

The image is not entirely positive. Though many centres have worked hard to establish a good reputation, trust in the sector is undermined by a steady stream of horror stories appearing in the mass media about false promises, hidden charges, and botched jobs that have to be corrected, often at great expense to the client or their own health services.

Far less visible are the ‘medical tourists’ who travel in the opposite direction, looking for high-quality treatment rather than a low price. People like Miljana generally head for medical teams with good reputations, but often have to rely on facilitators or agencies if they don’t have family connections in the destination country, or language skills, or familiarity with the bureaucratic procedures.

Far less visible are the ‘medical tourists’ who travel in the opposite direction, looking for high-quality treatment

The ‘patient touts’

Two years ago, the darker side of some of these services were exposed by two German journalists, in an article in Die Zeit titled ‘Patient touts’ (middle-men that go looking for customers), which won them the 2013 European Health Journalism prize. The article, which was republished in Cancer World (May–June 2014), exposed the extortionate payments being demanded by some agents, often well beyond the sum initially agreed, and with no attempt to provide receipts or a breakdown of where the money had gone.

More worryingly, it revealed systematic collusion between some private hospitals and the touts, with fees of up to 22% offered as a bounty for every patient brought in. Rather than providing a service to people who wished to get treatment abroad, these agents effectively act on behalf of the hospital, with a mission to convince patients of the benefits of getting treated at a particular facility.

The result, as was movingly told by one nurse, is that patients can use up their family savings on treatments that are never likely to benefit them, only to end up dying in a hospital bed far from home and all alone.

The increasing complexity of cancer diagnostics and treatment in the era of personalised medicine, and the rapid pace of new knowledge, puts pressure on patients even in more reliable health systems to search out the top international specialist for their particular cancer.

This is creating a market for supposedly “privileged information”, often of dubious value at exorbitant fees. One online service, run by a man whose CV shows he has never worked as an oncologist, offers to “act as the patient’s advocate” (original italics).

“We offer medical advice to the patients that come to us and we offer them to find the best possible medical solution …. We take them by their hands and walk with them. From being in the ‘cold’ you will now feel ‘protected’. Our patients feel empowered with their feet on the ground. With our assessment you will become a wise patient.”

What this meant for one breast cancer patient was a proposal that she should spend € 7,500 on a test for a set of genetic mutations that is available online at one-tenth the price, plus a further € 6,500 for having the results interpreted – which should be the job of her medical team.

She was warned against using any of the three oncologists she was considering – all leaders in the field of personalised treatment of advanced breast cancer – and was advised instead to use the agency’s own “find the top doctors in the world” service, which, for a fee of € 2,500, applies a custom-made algorithm with 33 parameters to a literature search for the specific pathology in question.

The advice amounted in total to spending € 16,500 before even consulting a single oncologist – let alone a world specialist!

The advice amounted to spending €16,500 before consulting a single oncologist – let alone a world specialist!

Stories like this are fuelling calls for greater regulatory oversight of the health tourism sector, including accreditation for the agencies and rules about what they can and cannot do. The call is backed by many players in the industry, some of whom have long been expecting a boom in business, and blame lack of consumer confidence in part for its failure to materialise.

The industry nonetheless feels in buoyant mood, not least in Europe, where private healthcare providers have gained new access to Europe’s massive public healthcare budgets through the EU Cross-border Healthcare Directive, which came into force in October 2013.

Why travel?

A number of factors are set to fuel a rapid increase in the numbers of people seeking to travel abroad for cancer treatment. The spread of “patient power” across Europe means more people are taking the initiative to find out what they need and where they can get it, rather than just settling for what they are offered.

The survival gap between east and west Europe, though not as dramatic as when it was first documented in the early EUROCARE studies, still persists, providing a continued incentive to travel to places that achieve better results.

This gap may well be widening again due to cuts in public spending, which are likely to spell the end of the relatively rapid improvement in survival rates that some of the worst performing countries showed in the 1990s and early 2000s.

This same austerity – public spending cuts and a fall in the number of people who can afford private health insurance – is also creating a “pull factor”, as hospitals in many west European countries look to attract patients from other countries to boost their budgets or fill empty beds, the self-same pressures that gave rise to the ‘patient touting’ reported in the Die Zeit article.

This was reflected at a high-profile International Medical Travel Summit in London in April 2015, where delegates from major hospitals in Italy, Spain, Portugal and the UK – including a major NHS hospital – mingled with delegates from facilities in more traditional health tourism destinations such as Dubai, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, the Philippines, Malaysia, Hungary and Poland.

Waiting times have also been increasing in public sector facilities, fuelled in some countries by public hospitals boosting their income with private patients, and in others by a rise in the number of patients relying on public healthcare, in the wake of widespread job losses and wage cuts.

However the real game changer may turn out to be the Cross-border Healthcare Directive – though exactly how, and how far, it will change the game remains unclear.

Cross-border Healthcare Directive

Contrary to the general public perception, this Directive does not in fact break new ground in giving EU citizens rights to treatment in other member states paid for from the public/social healthcare funds in their own country.

This has been possible for many years, not just for unforeseen necessary care – covered via the EHIC card – but also for planned care, via the so-called ‘S2 route’, which is still available, and is in some ways more generous than the Directive (see box).

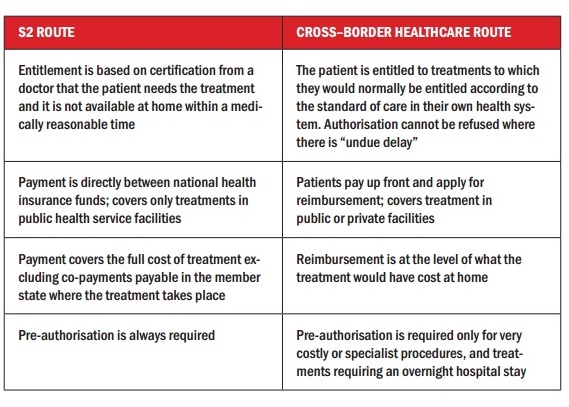

RIGHTS TO CARE IN OTHER EU MEMBER STATES

Citizens of EU countries have had the right to access treatment in other member states for many years under the Social Security regulations, which were first introduced in the 1970s and amended through a series of court cases (the S2 route) together with a number of European court rulings. The Cross-border Healthcare Directive was introduced to try to streamline and clarify this legal area, and introduces an additional route for accessing healthcare in other member states.

Citizens of EU countries have had the right to access treatment in other member states for many years under the Social Security regulations, which were first introduced in the 1970s and amended through a series of court cases (the S2 route) together with a number of European court rulings. The Cross-border Healthcare Directive was introduced to try to streamline and clarify this legal area, and introduces an additional route for accessing healthcare in other member states.

One important difference is that the Directive allows people to claim from their public/social health insurance at home to pay for private treatment abroad, so we may expect more US-style advertising (see below).

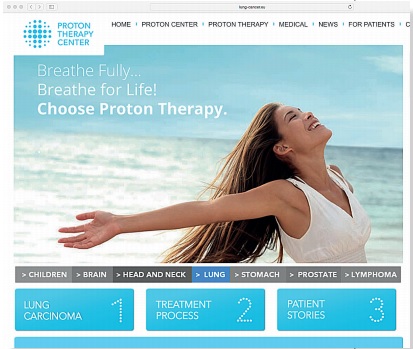

THE EUROPEAN CANCER TOURISM MARKET

Could the website for this proton centre facility in Prague (www.proton-cancer-treatment.com – accessed 11 June 2015) be a taste of what’s to come from Europe’s medical tourism market? This bizarrely inappropriate image is aimed at patients with lung cancer – a disease that is still fatal for more than four out of five patients even in countries with the best survival rates. The prostate cancer page (11 June 2015) claims a “97% curability” rate, and says the treatment has “no unwanted side effects”

Could the website for this proton centre facility in Prague (www.proton-cancer-treatment.com – accessed 11 June 2015) be a taste of what’s to come from Europe’s medical tourism market? This bizarrely inappropriate image is aimed at patients with lung cancer – a disease that is still fatal for more than four out of five patients even in countries with the best survival rates. The prostate cancer page (11 June 2015) claims a “97% curability” rate, and says the treatment has “no unwanted side effects”

Portugal, Spain and Greece are among many European countries that have seen strong investment in high-quality healthcare facilities over the past decade, but in the current economic climate, independent facilities are looking to fill spare capacity as more people drop out of private insurance.

With healthcare budgets increasingly stretched across Europe, public hospitals are also under pressure to find additional financing to make up for cuts in public spending. In recent years, NHS hospitals in England have been given the right to devote up to half (49%) of their total capacity to treating private patients – an opportunity some are using more enthusiastically than others. While profits from this private patients unit at the Royal Free London NHS Trust may be reinvested back into the NHS, diverting capacity to private patients adds to the pressure on waiting lists, which is forcing more people to “go private” – or to seek treatment in another European member state, via the Cross-border Healthcare Directive or the S2 route.

But, as Enrico Brivio, the European Commission Spokesperson for Health and Food Safety, explains, the Directive also contains some important elements that could have a broader impact on health systems across Europe. “Firstly, it establishes, for the first time in EU law, a set of rights that apply to all healthcare delivered anywhere in the EU: a right to a copy of a medical record; a right to make complaints or seek redress; a right to privacy and so on.”

But, as Enrico Brivio, the European Commission Spokesperson for Health and Food Safety, explains, the Directive also contains some important elements that could have a broader impact on health systems across Europe. “Firstly, it establishes, for the first time in EU law, a set of rights that apply to all healthcare delivered anywhere in the EU: a right to a copy of a medical record; a right to make complaints or seek redress; a right to privacy and so on.”

Secondly, he adds, there are articles that require a certain level of transparency from health systems, “for instance, on the way they seek to ensure quality and safety,” and also from individual providers, “for example, on treatment options and prices”.

For some patient groups, it is the potential to use these elements of the Directive to improve access to quality care in their own countries that is of particular interest, says Brivio. “There have been a large number of meetings with patient advocacy groups on the Directive in recent years… Some groups were interested in finding out how they could use the Directive to get better access to care abroad for their members – perhaps because they were facing problems of access in their own country. But there were certainly a large number of patient groups who thought that patient mobility in their particular patient group would probably remain low, but who were very interested in how the provisions in the Directive on transparency could relate to their own agenda for domestic healthcare reform.”

Eighteen months after the deadline for implementing the Directive, most governments have now incorporated it into their own national law, says Brivio, but questions remain in some cases over the quality of implementation. “Whilst we think that some member states have implemented the Directive rather well, we believe that we have identified a number of problems with the way that some member states have put the Directive into their national law,” he says, adding that the Commission will take legal action against non-compliant member states if needs be.

A cornerstone of the requirements on transparency and patients’ rights is the obligation on governments to provide a single National Contact Point where the public can access all the relevant information. A list of where to find contact points for each country can be found at http://ec.europa.eu/health/cross_border_care/docs/cbhc_ncp_en.pdf.

Who is travelling for cancer treatments?

Information about how far cancer patients use their rights to access treatment in other countries is hard to come by and largely anecdotal.

The European Cancer Patient Coalition is tracking use of the Directive, but its president, Francesco De Lorenzo, says it is still too early to tell. His personal perception, however, is that the Cross-border Healthcare Directive “works only in one direction”.

“If a particular healthcare service does not exist in my country, I cannot use the Directive to get it in another member state, so it doesn’t solve the economic problem behind patient mobility. The result is that it is easier, for instance, for an Italian to seek cheaper, but excellent care in bordering countries, like Slovenia, but it has been very difficult the other way around.”

One possible exception may be for patients with rare cancers, says De Lorenzo. The European Commission is committed to establishing European Reference Networks, which will link centres with expertise in specific rare diseases, with a view to catering for the needs of all EU patients, including those in countries too small to develop expertise in diseases that occur infrequently. “Rare cancer patients, therefore, will have the chance to travel abroad to seek care that otherwise would not be available in their own country,” says De Lorenzo. He adds, however, that while the Commission is supposed to cover part of the operating costs of the Networks, it does not have a commitment to cover all the costs related to the treatment of patients. It is also unclear how many Networks the Commission will decide to launch.

ECPC is calling for one network for each of the 12 rare cancer families. It is also calling for patients to be relieved of the requirement to pay up front for treatments they access under the Cross-border Healthcare Directive. “We have been advocating very loudly for the creation of a European fund, a pot of money at EU level, where all member states can get their payments back for patients’ mobility,” says De Lorenzo.

Zorana Maravic, from EuropaColon, says that in her experience, one of the main reason patients travel abroad is for a second opinion. A number of biological therapies have been approved in recent years for treating colon cancer, she says, but many countries do not reimburse them. Getting a second opinion from doctors in a country where these drugs are in routine use can help people decide whether or not it would be worth paying for the treatment from their own pockets. The cost of the second opinion itself, will almost always be paid for privately.

For Maravic, the big issue is educating patients about where they can get good quality treatment. “Sometimes the treatment is available even in their own country, but if patients aren’t aware of certain options, they don’t ask.”

EuropaColon’s priority is trying to ensure that people with colon cancer know, for instance, that they should ask to be tested for particular biomarkers early on in the course of their treatment to see whether they may be eligible for certain drugs.

Getting access to diagnostic tests – not just for relevant gene mutations, but also high-tech diagnostic imaging – could, in fact, turn out to be one of the most important uses cancer patients find for exercising their rights under the Directive.

Getting access to diagnostic tests could be one of the best uses cancer patients find for the Directive

This would seem to be supported by figures from the Royal Marsden cancer centre in London, which show that of 293 patients from other European countries seen over the past year, 376 diagnostic tests were carried out, but only half received any treatment.

There are signs that some patients with early breast cancer may be using the Directive to access breast conserving surgery that achieves better cosmetic results – or perhaps more reliable adjuvant radiotherapy. A well-known breast unit in northern Italy, for instance, reports a small but steady flow of Bulgarian patients who opt to pay the difference between the reimbursement they get from their government and the cost of the treatment.

But as the head of the Breast Unit at Lisbon’s prestigious Champalimaud Hospital, Fatima Cardoso, points out, it is patients with advanced disease, trying to access clinical trials that could help them, who have the most desperate need to travel. Yet this group is explicitly excluded from cross-border healthcare provisions.

On top of the costs of travel and accommodation, patients travelling abroad to trials have to pay the cost of all the treatment and supportive care other than the experimental therapy itself, which puts this option out of reach for most people, she says. Worse still, it seems that paying your own way for trials abroad may no longer always be an option. Cardoso recently got a young patient of hers accepted onto a trial at Gustave Roussy, only to be told that a condition of participation was that patients should have French insurance that would cover the costs of the “standard of care” treatments.

Cardoso’s frustration at the hurdles caused by this confusion and the expense involved in accessing trials in another country is widely shared. Ana-Maria Forsea, a Romanian dermatologist who has tried to help many melanoma patients access trials, comments that: “The procedures to obtain a reimbursement from the authority in one country to be on a trial in another are opaque, long, tortuous, and often the result comes fatally too late if ever.”

While the Cross-border Healthcare Directive was never intended to apply to patients being treated within clinical trials, it has been seen as offering particular value to small patient groups, such as those diagnosed with one of the rare cancers collectively known as sarcomas. Even here, however, the Directive does not seem to have made much of an impact so far.

Sarcoma expert Jean-Yves Blay, of the Centre Léon Bérard in Lyon, France, has devoted a lot of time in recent years to helping develop a network within Europe, and people approach him from other countries for second opinions, usually because his team has connections with their medical team, or because they have relatives in France.

He receives email requests for advice at least once a day, but it is still relatively rare for people to travel for consultations. “I see someone from overseas at my outpatient clinic maybe once or twice a month,” he says, “These are mainly people who have private insurance, or who are willing to pay for the travel themselves.”

Patients will also travel to his centre to participate in trials, but “only if they are able to get insurance to pay the costs that are not related to the trial.”

Markus Wartenberg, chair of Sarcoma Patients EuroNet (SPAEN), says the problem is not about access to second opinions, “It’s what you do with the second opinion in your home country, if top sarcoma surgeons or specific treatments are not available or are not reimbursed. Very often patients may be able to afford the second opinion, but unfortunately not the qualified treatment solutions in the west European countries – on top of all the costs of travelling between the two countries.”

SPAEN, he says, does not see travelling for treatment as a good solution. “Our vision would be to establish a Sarcoma European Reference Network that also supports upcoming sarcoma centres in east European countries. If at least one sarcoma expert centre per east European country would be available, this would help. We definitely need to raise the quality of diagnosis, treatment (including access to affordable drugs), and follow up in these countries to improve the situation.”

Wartenberg’s comment touches on one of the more contentious issues of the whole cross-border healthcare debate. If money is flowing out of weaker health systems to pay for patients to be treated in stronger ones, could that lead to the weak becoming weaker and the strong becoming stronger? If that happens, the Directive could promote a system across Europe that helps those who can afford to travel for treatment abroad at the expense of the majority of patients who need that money to be invested in their own health care systems.

The health tourism market

The world health tourism market is worth around € 34–48 billion, according to Patients Without Borders, but estimates vary widely. Cosmetic surgery, dentistry and fertility (IVF) treatments tend to be the services most sought after by people in western Europe. Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Turkey and Dubai are among the most high-profile health tourism destinations.

Increasingly patients are also travelling to central and east European countries. Poland is becoming known for cosmetic surgery, and Hungary for dentistry.

People travelling to western European destinations tend to be looking for more high-tech or specialist care for serious health conditions, including cancer. Germany and Austria are key destinations for eastern Europeans. France, UK and Italy also attract patients from abroad. More recently, Spain and Portugal have started marketing themselves as health tourism destinations.

The European Travel Commission has been asked to do a scoping exercise with the UN World Travel Organization, to define what the “health tourism” sector comprises, and get a realistic idea of the size of the market. They will put forward their findings and proposals this September at a meeting that will include the OECD and World Health Organization.

Early indications are that this definition could be fairly broad – covering everything from proton therapy, through to spa resorts and even guided spiritual walks through a forest. This is something the cancer community might do well to keep an eye on: branding guided spiritual walks as healthcare may not be a problem in itself, but it becomes one if it is promoted as an effective alternative to evidence-based treatments.

Leave a Reply