Most doctors believe in holistic care, yet the clinical guidelines they use, and the way they discuss and deliver care, rarely take into account the demands that a given treatment option will make on the patient and their daily life. Anna Wagstaff reports on calls for this to change. Additional reporting by Peter McIntyre.

A patient with advanced melanoma on clinical trials and a standard plan occupies roughly 50 hours a year of health professional time spread across all the multidisciplinary teams responsible for their care. That same patient, if they are fully adherent and engaged, will spend around 900 hours of their own time doing the best they can to support their own health and give their treatment the best chance of success.

These calculations were drawn up by Gilly Spurrier, who has become a bit of an expert in what it takes to be a ‘successful patient’ since her husband was diagnosed with advanced melanoma in 2010. For the past eight years, she has taken on organising every possible aspect of her husband’s life as patient, to free him up to focus on his ‘real’ life.

The 900 hours, she explains, gets eaten up by time spent ensuring the right medicines are in the right place and taken at the right time; travelling to and from consultations; undergoing treatments, blood tests, imaging; filling out forms; reporting side effects; setting up, changing and waiting for appointments; chasing results, liaising between different parts of their healthcare team; keeping up with the scientific and clinical trial developments; changing lifestyles; exploring how to control or adapt to side-effects, and sharing with other patients. And all this while sustaining a life beyond being a cancer patient.

“Being a cancer patient is a full time job,” says Spurrier. “If you want some normality, like non-patients have, then you have to be extremely organised and knowledgeable… Patients invest everything in their treatment and survival, much of which is unrecorded and unevaluated, but we are not nearly as good at managing and optimising the impact of it on our lives as engaged, chronic patients sometimes are.”

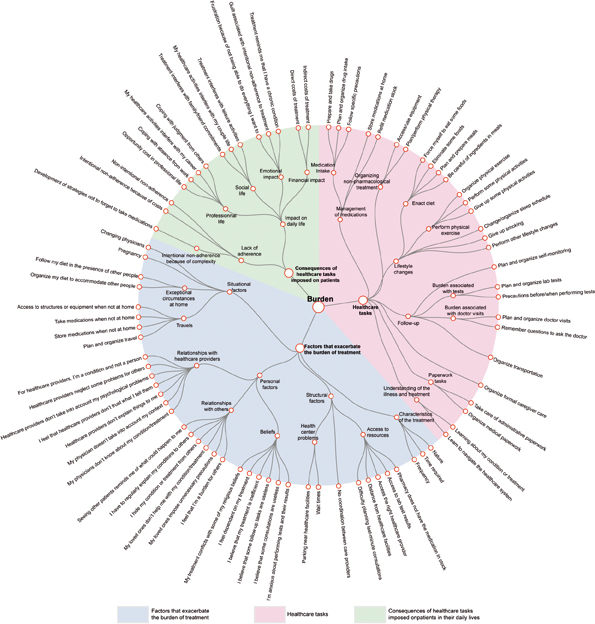

Source: V-T Tran et al. (2015) Taxonomy of the burden of treatment: a multi-country web-based qualitative study of patients with chronic conditions BMC Medicine 13:115, reprinted under a Creative Commons licence

She is not complaining. Spurrier knows full well that had her husband been diagnosed only a couple of years earlier, his prognosis would have been counted in months. Her aim is rather to flag up an under-documented consequence of cancer moving from an acute to a chronic disease, because she believes that acknowledging the increasing role patients have to play in their own care is the first step in enabling patients to work with the healthcare providers to plan and organise well enough to “live lives they would be happy with”.

Hans Scheurer, president of Myeloma Patients Europe, who was diagnosed with the disease aged 40, understands exactly where Spurrier is coming from. Changes in life expectancy may not have been quite as dramatic as in melanoma, but novel treatments and improved quality of care introduced in recent decades have seen 10-year survival rates in myeloma triple for women (from 9.8% to 28.1%) and quadruple for men (from 8.9% to 36.6%) between 1991–95 and 2010–11 (figures for England and Wales).

“There are so many new options, and we are very happy with those new treatments, but they give us a unique set of new challenges to living with cancer,” he says. “You have to go to the hospital more often, and it is more disruptive in your daily life. It is certainly a big topic among cancer patients.”

As Scheurer points out, and contrary to popular perceptions, many of the new drugs are not oral treatments, and need to be given in hospitals, and because oncologists are still learning about their impact, patients need more frequent check-ups to monitor the effects. They also come with new side effects, which then require further monitoring and treatment.

“That gives new options, new treatments, new visits, and new things to make decisions about. Before you know it, you are living with cancer full time. For a lot of cancer patients that is the reality. You live longer with your disease, which we are very grateful for, but the challenge is: How do you do that? How do you live with your cancer when you want to work and you have a family and you want to go on holiday?”

Burden of treatment

The problems that Scheurer and Spurrier are alluding to have been given a name: the burden of treatment. The concept was first mentioned in the context of chronic conditions such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and diabetes. The challenge of meeting the needs of the growing number of patients, particularly elderly patients, with multiple chronic conditions, prompted a group of medical researchers in Paris to team up with a group at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, USA, to develop the concept and a tool to measure it.

Every month when I have an injection I am meant to have a blood test a few days before. Every second time I forget about the blood test, because you try to get on with your life but you forget about the things you are meant to do.

“There are a lot of patients I know whose disease is very stable, but they might be on a watch and wait, they may have a scan every 6 or 12 months if they are lucky, whereas with me it is every three months.

“That takes a whole day, but I get anxious for days before, and then waiting for results. Often medical staff don’t realise that once you’ve had a scan, you actually want to know what is happening. I’m very lucky that I have a great team of doctors looking after me. But I also learnt to ask the questions – if I don’t hear anything, I’ll chase it up.

“I’m lucky I don’t have to work full time, because this cancer is like a part-time job anyway, with how much time it consumes, even in your thoughts.

I try not to let it stop me doing things, because it ends up consuming you.

“Every second time I forget about the blood test,

because you try to get on with your life”Katie Golden, Australia, on being treated for neuro-endocrine tumour

A 2012 paper by Viet-Thi Tran (Paris Diderot University) and colleagues, presenting an ‘instrument to assess treatment burden’, defined it as “the impact of health care on patients’ functioning and well-being, apart from specific treatment side effects” – a metric that “takes into account everything patients do to take care of their health”.

The authors used the tool to describe and classify the components of the burden of treatment from the patient’s perspective, based on survey responses from more than 1000 patients from 34 countries with different chronic conditions. The ‘taxonomy’ of burden of disease they came up with, shown opposite, is an impressive attempt to bring together the many different ways that ‘the work of a being a patient’ can impact on their daily lives.

It may be just a description/classification, but for patient advocate Gilly Spurrier, that study represents the first step in getting to grips with a burden that can make patients’ lives a misery. “This is the starting point of learning to manage time and the disease more effectively, in times of rationed healthcare,” she says. And so it is.

Minimally disruptive treatment: the concept

Developing in parallel with the ‘burden of treatment’ concept and taxonomy, and also led from the Mayo Clinic, is the concept of ‘minimally disruptive medicine’.

A 2015 paper published in a Scottish medical journal, with input from both the Mayo Clinic and the University of Glasgow, describes it in transformative terms as a concept that supports ‘a new era of healthcare’ (J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2015, 45:114–7).

“Minimally disruptive medicine,” they say, “is a patient-centred approach that asks the question: what is the situation that demands medicine, and what is the medicine that the situation demands?”

Getting the right answer, they stress, requires understanding the burden and the patient’s capacity, and crucially also, “reshaping the working relationship of patient and clinicians, adjusting goals, shared decision making, streamlining medications and strengthening relationship with the community.”

Central to this is a recognition that clinical guidelines are developed with a focus purely on clinical outcomes, and fail to take into account either “the capacity, abilities and limitations of patients to manage their daily care,” or the impact on their lives of the workload, demands and responsibilities that accompany these treatment regimens.

“Concepts such as workload, burden and capacity direct attention to the situation in which the patient and their carers exist while living with illness. Importantly, these concepts also direct our attention to issues which healthcare and clinicians are often blind – the extent to which healthcare-created burden inadvertently drags people down,” say the authors.

Minimising disruption for cancer patients

The heavy demands that adhering to cancer care plans places on patients is a big concern for Helena Ullgren, a nurse specialised in head and neck cancers, based at Stockholm’s Karolinska hospital. Ullgren is responsible for coordinating all the ‘contact nurses’ in her region, who are assigned to individual cancer patients to help them navigate through the complexities of their healthcare.

“The consequence of treatment is not just coming to hospital on the day,” she says. “Aside from the side effects, it is all the practical stuff. We demand patients take blood tests; usually they have to go to hospital or their GP, or perhaps if they are lucky they have a homecare team that will cover blood tests. It’s not that you can take them on a random day, you have to take it on an exact day.”

There can also be a lot of anxiety and disruption attached, she adds, because if their blood tests show they have not recovered sufficiently from the previous round of treatment, they may have to postpone the next one, “and then their whole schedule will be upset.”

Many patients undergo regular X-rays to evaluate the impact of their treatment. “That can be a big thing, particularly if you are old, or you live maybe an hour away. To do the X-ray you have to first take a blood test, then you go and do the X-ray, which is another day of travel, and then you go back again to the physician to hear the results.

“I’d say some patients are overwhelmed by the practical stuff that treatment leads to.”

The most disruptive thing of all, reckons Ullgren, is the poor coordination between the different elements involved in one patient’s treatment, which are many, as she explains. “For instance, patients with head and neck cancers can go to both the outpatient and inpatient clinic, radiotherapy clinic, the dentist within the cancer care setting, the dietician, speech therapist and chemo clinic.”

As she points out, that doesn’t take account of any additional conditions the patient may be receiving treatment for. And the problem isn’t only a failure to streamline different aspects of treatment, to minimise the number of locations and visits a patient has to make, says Ullgren. It is that the job of coordinating, to ensure that the right things happen in the right order, and that referrals actually turn into appointments, often falls to the patient themselves, adding substantially to their workload.

“Patients spend a lot of time calling first one care giver, and then the other. They are often the messenger between the two, and that is something we can improve in general,” she says.

She feels that, within the cancer setting, cancer clinical nurse specialists have an important coordinating role, but that everyone involved in providing cancer treatment and care also has a responsibility to work in a coordinated way, rather than in silos. When it comes to patients also being treated for other chronic conditions, she feels a single primary care contact with responsibility to keep track of all the elements of their care could be helpful, and mentions the UK general practitioner system as particularly suitable for this role.

Easing disruption, negotiating goals

Paul Cornes, an oncologist based in Bristol, England, has been a supporter of minimally disruptive medicine since before the concept was named. His interest in value-based medicine has led him to focus on key aspects of minimally disruptive medicine to improve adherence to care plans and improve quality of life.

He argues that, while evidence-based guidelines describe the most effective treatment for the disease, choosing the best option for an individual patient means offering them the chance to trade-off a small percentage of efficacy for reduced side effects or reduced burden of treatment.

He mentions adjuvant radiotherapy in early breast cancer as an example. “You can have your conventional five or six weeks postoperative radiotherapy. You can have the short course as exemplified by the Royal Marsden and Canadian research – just two or three weeks’ treatment. Or you can now have these intraoperative machines where you have the radiotherapy at the time of your operation, and if you have a low- or moderate-risk tumour, you can just stop there and say the extra advantage of another five weeks of treatment is so minimal that you probably won’t want it.” For a woman with lots of nodes that extra treatment might be very worthwhile. “You can have that discussion, but how many patients are offered that?”

Evidence from many countries shows that patients who live further from treatment centres are less likely to attend adjuvant radiotherapy, so offering a more practical alternative makes sense, says Cornes. “Would you rather that 100% of your patients get 90% of benefit, or will you try to strike 100% all the time, and leave lots of patients untreated?”

Treatment for women with endometrial cancer is another example, he says, where intravaginal brachytherapy can be an alternative to five weeks of pelvic external beam radiotherapy as adjuvant treatment, particularly for patients with comorbidities. “There’s a simpler treatment that can give 95% of the benefit – would that do?”

He wonders too whether Herceptin-eligible patients are ever told that nine weeks’ treatment (standard in Finland) is an option that has been shown to offer near enough the same benefit as the 52 weeks that is standard everywhere else.

Cornes would like to see changes in the way guidelines are developed and implemented, to include a range of options with information about pros and cons, to allow patients a real choice, and says this approach is backed by advocacy groups: “They don’t say: ‘our patients must have the very best,’ they say ‘the very best for them’.”

Of course, chemo took a full day every time. There were additional appointments for bone scans as there was concern of the cancer having spread to the bones. There were plenty of CT scans to see whether the treatment was working. I also needed radiotherapy and visits to see my surgeon. These were in two different hospitals, quite a distance from my home. The addition of a biological drug also meant travelling to a private hospital as the NHS refused me this medication. Nothing was made easy and you can imagine that when you put these appointments together, it easily involved four days out of seven”.

“Nothing was made easy…

when you put these appointments together,

it easily involved four days out of seven”“I never attempted to work during my two years’ of treatment. But my husband had to continue with his work while taking me to all these appointments. I think we should appreciate and care for the carer. They have to continue with their routine and often find themselves in an impossible position along with the worry and feeling of helplessness.

Barbara Moss, UK, on being treated for advanced colorectal cancer

One-stop clinics

Changing the way services are organised and delivered could also do a lot to lighten the burden of treatment, says Cornes. He points to the ‘one-stop’ bone pain clinics that have been running in Canada and Norway for many years, as good examples.

“There are few more successful things than a single dose of radiotherapy for bone pain,” says Cornes. “You go into a clinic in the morning, you have all the scans, the treatment planning is done on the spot, you get your treatment, and go home at the end of the day with your post-treatment instructions.”

There’s no reason why something similar couldn’t be done in other countries, he says, but it would require changing the way treatments are incentivised and rewarded.

If a patient of his mentions bone pain at a consultation, says Cornes, it would be logistically possible for that patient to be taken downstairs to get a scan on the spot, and have their one-off shot of radiotherapy planned and delivered there and then. But without the right procedures, staff and budgetary mechanisms in place to make that happen, patients end up instead being referred to a separate imaging appointment, which would inevitably be followed by a further appointment for the treatment, possibly weeks later.

The future, he believes, is for more cancer services to be delivered at a community level, as is happening with cardiology services in his part of the UK.

With the right level of training, and access to local facilities, they could take care of routine tests, discuss the results, prescribe or adjust certain medications, and administer infusions or injections or supply oral treatments along with advice about how to take it and why – all within the same day.

The ageing population and the higher prevalence of multiple comorbid conditions, particularly among older patients, means that services are simply going to have to work out how to reduce the burden of treatment, says Cornes, because following evidence-based management guidelines for managing diabetes, high blood pressure and cancer is neither feasible nor desirable.

Signs of change

Patient advocates are already arguing for some of the changes Cornes is calling for, says myeloma advocate Hans Scheurer. He has been discussing with other European cancer groups and health professionals about how to press for more home-care options.

“There is a desire to look at alternatives. There are a lot of hospitals busy talking about how you can go with this, and we also stimulate patient organisations to do so, because it is absolutely of benefit to patients to have treatment at home. Blood tests could be at home.

“Maybe we can look at some kind of ambulance that can drive around with options to do chemotherapy at home, especially for frail patients. This is an idea we have discussed with health professionals.”

One such service has been operating in the Netherlands since 2015, he says. Working in close cooperation with particular hospitals, it administers infusion therapy at home, including anti-cancer immunotherapy. “Of course you need specially trained nurses to provide this service, and they work closely with the doctor, as they would in the hospital. But this is absolutely a welcome tailor-made solution for a group of cancer patients – it is the future we are looking at.”

Not all cancers are the same, however, and nor are all cancer patients. How much does the burden of treatment matter to people with advanced melanoma, whose priority will be staying alive long enough for the next experimental treatment to come along?

It matters, says Gilly Spurrier. “Clinicians and health systems expect patients to just accept that their lives must contain long periods of waiting and that they are resigned to the inefficiencies of healthcare which impact on their lives. There is an almost unspoken rule that a patient ‘becomes their disease’, and that patients should not be surprised that life is so heavily impacted. The assumption is that: ‘Well, you are alive, be grateful for that.’ For me, this is not acceptable.”

As important as lightening that burden, she argues, is simply recognising and acknowledging the amount of time that patients spend on self-care, the contribution they make to their own health and disease outcomes, and above all the expertise that they build up on the way.

“I think it is important for patients to recognise this,” says Spurrier, “as it shows them how much they have invested, how much they know, and hence why they should be drivers of their care… Now we ration healthcare and have more individualised treatment regimes, it is essential both for the patient and the healthcare systems that patients take charge.”

It is also important for healthcare providers, researchers and administrators to recognise, she adds, because patients who invest the time and effort into adhering to their care plan, and doing everything they can to promote their health and well-being, not only save money, time and resources in relation to their own care, but they also represent “a hugely under-used expertise in research into improvements in healthcare,” says Spurrier.

If health services are researching ways to improve the personalised treatment they deliver to growing numbers of patients needing complex care, why wouldn’t they want to involve the people who devote half their lives to learning to live with and overcome their disease?

Some patients are being asked to travel up to 100 kilometres for radiotherapy, and elderly patients who have no support often abandon treatment rather than make the journey. I completely understand that, in the middle of winter, if you are 75, immunosuppressed and receiving chemotherapy, and you need to go to take two buses and then walk 20 minutes, they say I won’t do it, even if it is only 25 kilometres. In Spain the carer is usually a member of the family, and it is difficult for them to go because they need to keep working and pay the bills.

“Patients who have no support

often abandon treatment

rather than make the journey”Natacha Bolaños, advocate with GEPAC, an umbrella group for Cancer Patients, Spain

Leave a Reply