The ABC conference on advanced breast cancer gives centre stage to a group of patients who feel theyve been marginalised and their needs ignored for too long.

People who have been treated for early-stage breast cancer have many issues to handle, not least the fear of a recurrence. However, the advocacy and support movement for this large group is strong. That has not been the case for those with metastatic disease, who not only have to cope with an incurable condition, but have faced isolation from the mainstream breast advocacy movement, and also from health professionals and society in general.

A recent survey of women with advanced breast cancer in Europe, presented in a report called ‘The Invisible Woman’, found that more than half feel they are perceived negatively by society, and only 36% said they had received help from patient groups. Many also said they suffer from psychological, physical or financial problems. A majority want improved access to treatment and better access to, and interactions with, healthcare professionals.

The organisers of the Advanced Breast Cancer (ABC) conference, which held its second meeting in Lisbon in November 2013, are determined to change this picture by including advocates – many of them patients – and also health professionals such as nurses and psycho-oncologists as an integral part of the event. Presentations from them are a part of the main conference, and the opening keynote is from a patient or patient advocate.

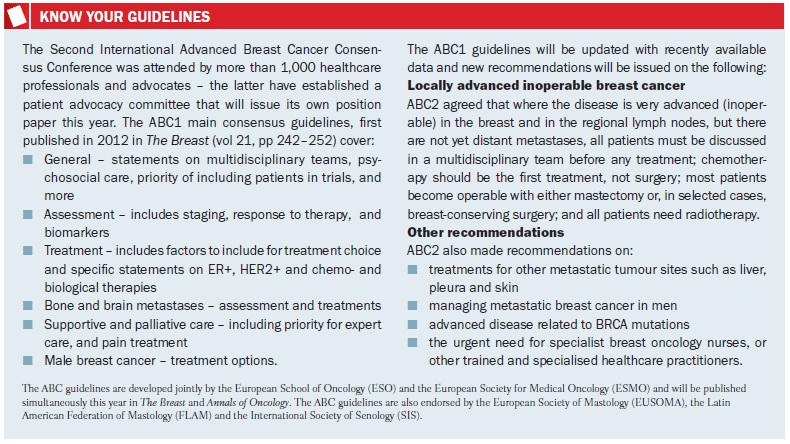

ABC is mainly a consensus-setting conference – its primary aim is to produce and update a set of international guidelines for the care and treatment of people with metastatic and locally advanced disease. Advocates also have the opportunity to make the case for changes to the wording and scope of recommendations, and get to vote alongside clinicians.

ABC2 had probably the largest and widest international gathering of metastatic breast cancer advocates so far – some 50 organisations from 25 countries. A special set of meetings, organised by an advocacy committee, was dedicated to their particular concerns. While most advocates were from organisations that represent people with all types of breast cancer, there are now some who have formed groups specifically for those with metastatic disease, and also for people such as young women and those with inflammatory breast cancer. Everyone there recognised that people with advanced cancer are a special group who need and deserve much more support from the medical community and also society at large.

This is how it is

No one understands this better than Doris Fenech, a breast care nurse and advocate from Malta, who has advanced breast cancer. In a powerful and moving keynote address she talked about what women typically go through when living with advanced disease. “I look well and no one imagines I have metastatic cancer and am receiving chemotherapy, and that the cancer cells will overpower my body,” she said, detailing also the series of symptoms and diagnostics she went through after a primary breast cancer recurred more than 10 years later.

In a candid account, she told the audience of the ‘advantages’ of having the disease – how she has become more assertive and does what she wants, today; how, despite the lack of support for people with advanced disease, she found much help from Europa Donna, the European breast cancer coalition; how crucial this support is, given how hard it can be to talk to family and friends; and how she can prepare for her departure.

“I look well and no one imagines I have metastatic cancer and that the cancer cells will overpower my body”

Disadvantages she gave as physical pain – a good treatment plan is crucial. She said she thought she could cope with chemotherapy again, as she had with primary cancer. “I was not sick but the fatigue is unbearable. With chemotherapy for early cancer there is fear of the unknown, but hope; with metastatic cancer it is more likely ongoing treatment and something you have to live with.”

There is a tendency to withdraw from a supportive family to spare them pain, she added. “This can be counterproductive, as they feel they have done something wrong. My life revolves around what I face – I don’t plan for old age, and I regret that I may not see my daughters getting married or see my grandchildren.”

For most health professionals the diagnosis is the beginning of the end, she said. “They are often at a loss for what to say. We have different social and emotional needs… and have been isolated and marginalised by the media and the public.”

Doris Fenech made a strong appeal for equity in treatment – to be included in clinical trials, and to receive treat¬ments that could give a few months of life and enable her and others to see milestones in family life. “Treatment is our lifeline,” she said.

Her talk also covered many other points about day to day living and the emotional rollercoaster people go through. All of these were explored in detail in the advocacy stream, which was packed with not only patients and advocates but also others from the conference.

Towards a chronic disease?

Fatima Cardoso, head of the breast unit at Champalimaud Cancer Centre in Lisbon, and one of ABC’s four chairs, gave an update to the advocacy group on progress in the aim of transforming metastatic breast cancer into a chronic disease. There are more women and men now living beyond the usual two- to three-year median survival, she said, but mixed pro¬gress in the three main cancer subtypes. True advances have been made in HER2-positive disease, which used to have a poor outlook, but little progress in hormonal (ER-positive) breast cancer since the 1990s, when aromatase inhibitors were introduced. Triple negative disease has also seen little progress in treatments, but is becoming better understood – it is now known to be a group of some seven to ten further subtypes, she said.

Cardoso gave a reminder of the importance of guidelines – how they have improved survival and quality of life in early-stage disease, and could do the same in the advanced setting. Already, the first ABC guidelines, issued in 2012, have been widely presented and implemented in some countries. But research has been painfully slow. “It took us ten years to understand that it’s important to give trastuzumab [Herceptin] after progression, and ten years to understand the best dose and regimen for paclitaxel [Taxol] in the metastatic setting. This isn’t good enough,” Cardoso said. There are many unanswered questions about evaluating new treatments, she added, and it’s as much, or even more, important to individualise treatments than for early breast cancer.

“It took us ten years to understand the best dose and regimen for paclitaxel in the advanced setting”

Cardoso also summarised other recommendations she feels advocates can lobby for around the world. “Treatment in multidisciplinary teams is obvious, but not always done even in the West,” she said, adding that medicine should be evidence based and not ‘eminence’ based – not in the hands of single oncologists who think they know best. Psychosocial support is needed from the start, clear explanations of the cancer and treatment must be given, including that there is no cure, and patients with advanced disease should always be accompanied to appointments.

Advocates had ample time to develop these themes as a large group and also in regional workshops. Access to treatment and to multidisciplinary teams are at the forefront of concerns – many countries currently do not have such teams, let alone specialist breast units, while the cost and availability of the latest drugs is also a serious barrier to optimal treatment. Lack of resources is not confined to poorer nations, but the problem is on a different scale: it was mentioned that in some countries such as Thailand it can be a struggle even to see an oncologist.

The wide spectrum of resources – from the comprehensive cancer centres of the West to countries where it may be difficult even to administer intrave¬nous drugs – is a big challenge for those drawing up international guidelines. While there are no compromises about recommending optimal treatment, based on evidence, and also passing expert opinion about issues such as the need for multidisciplinary teams and psychosocial support, it is recognised that costs and available resources need to be taken into account.

For example, among the guidelines updated at ABC2 is a recommendation on the importance of patients having access to specialist cancer nurses (preferably breast care nurses) – it is vital to have a ‘navigator’ for treatment and support. The recommendation has been amended to recognise that the role could be provided by training other health professionals or doctors’ assistants.

Markers of best practice

Having representatives from many parts of the world helps to put down markers of best practice – although again it was striking that even the most developed nations reported patchy provision for people with advanced disease, and also much to do on the advocacy front to fully include them in breast cancer work. Yes, there are specialist breast units, and the start of an accreditation system for them in Europe – but are they seeing enough people with advanced cancers, and are they employing an appropriate mix of professionals such as psycho-oncologists and gerontologists? Are breast care nurses tied more to early-stage surgical teams and not being given time to develop supportive skills for people in the advanced stage of cancer? Are patients being given the right information and an honest account throughout? Are advocacy organisations using the right messages and information to connect with people living with advanced cancer?

Even in the largest and most prestigious cancer centres and breast units, some patients with advanced cancer are not discussed at tumour boards.

In Europe, Susan Knox, executive director of Europa Donna, says a key milestone was the publication in 2006 of guidelines for quality assurance in screening and diagnosis. This 400- page document sets out the requirements for specialist breast units, and has been the keystone for lobbying by member organisations that now number 46 countries in and around Europe. Accreditation work for units is ongoing, and Knox says that a priority for Europa Donna is for people with advanced disease to be treated in breast units, which is not yet widely happening for reasons such as lack of trained staff.

Europa Donna, she adds, has done its own informal survey of member countries, finding that only a third say women with metastatic disease are given enough support at the time of diagnosis, and a large majority agreed that there is a need to advocate for special rights for these women with regard to information, treament and counselling. This could lead to national interest groups being established for people with advanced breast cancer, in a similar way to groups for young women with breast cancer that have appeared recently, says Knox.

As one advocate also commented, messaging is so important for involvement and for destigmatising the illness. “They don’t want to hear about diet and exercise – we need to tune our messages to the new ‘normal’ in their lives, and help with the isolation they feel.” It was also noted that the word ‘survivor’ is not appropriate for those with advanced disease, as it is not how women see their lives of daily coping and ongoing treatment.

Advanced advocates

The US already has advocacy groups for metastatic patients, including MBCN – the volunteer-run Metastatic Breast Cancer Network – whose president Shirley Mertz played an active role at the conference, and METAvivor, also run by volunteers. METAvivor’s director of advocacy Dian Corneliussen- James – known to all as ‘CJ’ – is living with advanced breast cancer herself, and also played a leading role at ABC2 in discussions and presenting a summary of the advocacy sessions to the conference. METAvivor was set up to fund research into metastatic cancer – rather than as a support group – and is fiercely independent in pursuit of its mission, says CJ, who notes that there is only a low percentage of cancer research funds being spent on metastatic disease, in particular in the US.

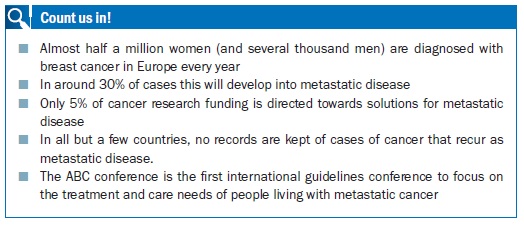

“The minute you say to someone you have breast cancer, they think you are living longer and longer and the disease is virtually chronic now,” says CJ. “There’s nothing chronic about two to three years survival after diagnosis, although there are outliers such as myself.” The proportion of women who go on to have metastatic breast cancer is 30%, and METAvivor wants to see 30% of cancer research funding dedicated to advanced disease – six times the current estimated average in the western world of around 5%.

“There’s nothing chronic about two to three years survival after diagnosis”

Duplication of effort in the advocacy movement is a big concern for CJ, and she agrees that there are too few patients at conferences: “We can speak for ourselves – I was delighted to see Doris Fenech speaking at ABC and it is a dream come true to come to a conference that focuses on our disease” – although as she says, all women would rather be spending time with family or doing their usual work rather than “working round the clock on these issues”. At the other end of the spectrum are well-staffed broad advocacy groupslike Breast Cancer Network Australia (BCNA), whose CEO, Maxine Morand, is a former minister for children in the Australian state of Victoria. “We are a member-based organisation and connect to patients through breast care nurses, who register them for our resources, such as the My Journey kit, which present information about clinical and supportive care,” she explains. The network has recently updated a resource for women with advanced cancer with information tailored to the site of the spread. “Information is incredibly important,” says Morand, noting that there is also a very active online presence where women can network with others in similar situations. BCNA has also been successful in lobbying for access to drugs such as trastuzumab and is now working on gaining reimbursement for regular bone scans for women taking aromatase inhibitors, she says. Fighting for funds and reimbursement is a common theme.

Advocating on many fronts

Advocating on many fronts

An impressively wide range of issues were discussed at ABC – a reflection of the growing awareness that people who are living with advanced breast cancer need a broad set of care and support options – if any one is missing or poorly available, it can have a major impact on their quality of life. It underlined CJ’s point about the need to avoid duplication and use advocacy resources wisely.

There were sessions on optimal pain control, psychological support, patient perspectives on symptoms, and global disparities in access to supportive and palliative care. Changing the parameters for drug research to give quality of life far more attention was a frequently raised issue, not least by psycho-oncologist Lesley Fallowfield, and Musa Mayer, an advocate who runs AdvancedBC.org, both of whom sit on the ABC guidelines consensus panel. Improving the overall research climate for breast cancer was another major topic, but participants stressed that this must not come at the expense of other practical concerns that also need to be addressed. Prominent among them are funds and consistent support from local services for home care and home adaptations, social security payments for those not able to work, a requirement for employers to grant flexible working hours to fit in treatment, and a range of rehabilitation services, which need to cover areas such as sexuality and complementary medicine. Pain and symptom management, and the early introduction of palliative and supportive care, are also crucial and often poorly given.

Underpinning it all is a big frustration for advocates – the lack of information about how many people are living with advanced cancer. Most cancer registries record primary diagnoses and mortality, but not recurrences, so there are only estimates. There have been campaigns to change this. In England, a pilot has been run on collecting data on recurrent and metastatic breast cancer from current mandated sources, and to see how this could be integrated with data flows to cancer registries.

As a report on the pilot puts it bluntly: “The lack of information on recurrence and metastasis of breast cancer means that the effectiveness of treatments for primary cancers cannot be adequately assessed and the care of patients with recurrent and metastatic cancer cannot be fully evaluated.” It was advocates who pressed to change this.

In a ‘meet the experts’ session at ABC2, where advocates were able to put questions to some of the world’s top oncologists and other professionals, there were equally blunt comments – not least that advocates should get more angry about the lack of progress. Larry Norton, ABC co-chair based at Sloan-Kettering in New York, said: “We probably know how to cure metastatic breast cancer” – it’s a matter of looking better at the data, while Martine Piccart, from Jules Bordet Institute in Brussels, added that research teams are sitting on data for far too long, and women who take part in studies should say it is unacceptable not to share data.

As one advocate said: “Informed patients make better doctors” – and the ABC conference is helping to put more patients in the driving seat.

Leave a Reply