The side effects of targeted drugs are poorly documented, and their impact on patients frequently seriously underestimated and undertreated. Efforts to address these issues could improve survival as well as quality of life.

The image of an exhausted patient with bald head and pale drawn face has almost come to ‘represent’ treatment with chemotherapy, the visible sign of interior pain and discomfort.

The image of an exhausted patient with bald head and pale drawn face has almost come to ‘represent’ treatment with chemotherapy, the visible sign of interior pain and discomfort.

The language of targeted treatments has a different imagery. The rational approach, precision medicine and designer drugs constitute magic bullets attacking the cancer without harming ‘innocent civilians’. Patients treated with these therapies will not just do better – they will look and feel better.

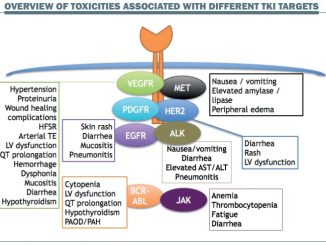

Therapies designed to block pathways that allow cancer to invade cells or that boost immune defences do indeed cause less harm than cytotoxic drugs, but that does not mean there is no collateral damage. A range of side effects are reported by patients – neuropathy, tiredness, bone pain, nausea, persistent diarrhoea (or constipation), persistent headache, skin rashes, mouth ulcers and others. In some cases a reaction may even indicate that the drug is having a positive impact.

However, adverse effects do not always emerge during research trials where patient numbers are small, or in trials on patients with advanced disease, where the focus is on survival.

Most targeted therapies are self-administered, and in the case of successful treatments may require a patient’s commitment for months or years. But if patients are given no information about what to expect, or support to alleviate symptoms, they may interrupt treatment without their doctor being aware of it.

The information gap

Ethan Basch, Director of the Cancer Outcomes Research Program at the University of North Carolina, has long campaigned for the patient perspective to be included in research. “Early in my career, it was very obvious that we were under-appreciating the impact drugs were having on people’s day-to-day experiences,” he says. “I recall an early phase II clinical trial where the physicians and nurses recognised that almost every patient had very severe fatigue and that was the reason why almost everybody went off the trial. Yet if you looked at the data you would not think anybody had fatigue.”

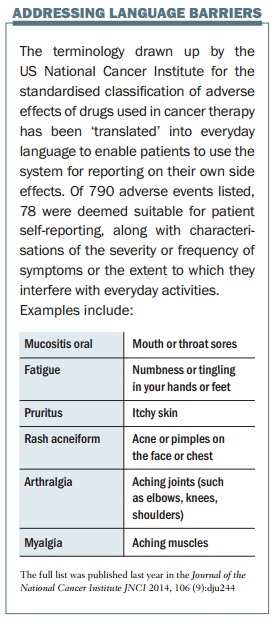

Since 2008 he has been leading a US National Cancer Institute process to adapt a clinical tool to give patients an input, through a patient-reported outcomes version of the current Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). This is a web-based platform to collect patient reports of treatment symptoms, asking about frequency, severity, and interference with daily activities. So far, 80 symptoms have been converted using patient-friendly terms such as “aching muscles”.

Since 2008 he has been leading a US National Cancer Institute process to adapt a clinical tool to give patients an input, through a patient-reported outcomes version of the current Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). This is a web-based platform to collect patient reports of treatment symptoms, asking about frequency, severity, and interference with daily activities. So far, 80 symptoms have been converted using patient-friendly terms such as “aching muscles”.

Basch hopes it will be widely used: “Targeted therapies make the need for this kind of tool much more pressing. A lot of these products come to clinical trials in first-in-man phase I studies, and we really have no idea of what the side effects are going to be. Many side effects are patient experienced and that makes these kinds of peer tools very important for product development.

“Oral outpatient medications depend on people being compliant or adherent with taking the product, and we know from multiple studies that people who experience a lot of symptomatic side effects stop taking drugs.

“For me the advent of oral biologics as targeted therapy has strengthened the argument for patient-recorded tools to measure toxicity. There is an opportunity in the post-marketing stage to collect this information in the real world and use it to guide symptom management and clinical practice. We need to educate patients so they know what to expect.”

“The advent of oral targeted therapies has strengthened arguments for patient-recorded tools to measure toxicity”

Dying from cancer or living with it?

A critical factor in willingness to tolerate side effects is the patient perception of what the drug offers in terms of survival and remission.

People with chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML) today have such good survival prospects on imatinib and other TKIs that quality of life issues become very important.

The CML Advocates Network (cmladvocates.net) conducted a study of more than 2,500 CML patients in 79 countries, which highlighted how some patients have put the stability of their response at risk. Jan Geissler, co-founder of the patient network, says: “Many patients decide not to take their drugs as prescribed, to reduce fatigue, gastro-intestinal issues and skin issues. The side effects don’t kill people, but over a long period can make them feel unhappy, especially since most CML patients do not experience symptoms before diagnosis.”

“Many patients don’t take their drugs as prescribed, to reduce fatigue, gastro-intestinal issues and skin issues”

Geissler notes that the average age of CML patients on phase III trials was 47 while the average age of real world patients in Europe is nearer 65. “Phase II and III studies usually do not uncover low-grade side effects, because they may occur in an older population with comorbidities or are not recorded well. It is over the long period you see them.”

There can also be unexpected reactions. About 7% of patients on dasatinib need water to be drained from tissue around the lungs, while on another drug there is increased risk of heart damage to older patients who have existing cardiac conditions.

There can also be unexpected reactions. About 7% of patients on dasatinib need water to be drained from tissue around the lungs, while on another drug there is increased risk of heart damage to older patients who have existing cardiac conditions.

At the other extreme, patients with advanced melanoma, which has a very poor prognosis, may see a dramatic improvement from BRAF and MEK inhibitors, although these drugs can also cause fatigue, thinning hair, skin rash or sunburn (one group of patients on vemurafenib refer to themselves as “vempires” because they have to shun daylight!)

Molecular biologist Bettina Ryll lost her husband Peter to melanoma and now runs the Melanoma Patient Network Europe. “By the time my husband had his diagnosis in March 2011 the tumour was already very large. It grew at an amazing speed down his arm and basically encased his elbow joint – you would wake up in the morning and could see that the tumour had grown. He had a lot of pain.”

Peter Schoonjans joined a trial of the MEK inhibitor trametinib in London in 2011 and almost immediately the tumour started shrinking at the same speed as it had grown. Bettina Ryll said that side effects – rash, dry skin, joint pain and hair loss – seemed trivial compared to the miraculous benefits.

“He needed less pain killers; he could move his arm and his hand again. His quality of life was so much better. I thought people were exaggerating when they talked about side effects.”

Peter Schoonjans developed resistance to the drug and died less than a year after diagnosis. Nevertheless trametinib gave the family precious time and golden memories. “We were in a situation where it was very clear he would not live and you make allowances for that,” Bettina Ryll said. You are glad of every week you get out of it.”

She now understands better how patient experiences can differ. She recalls how the co-founder of the Melanoma Patient Network Europe (who has since died) suffered with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib. “I remember thinking how different our perceptions were of the same class of drugs. Patients like my husband were above all grateful; seeing the tumours regressing was magical and we just treated the side effects. Patricia was on the drug for longer and had severe joint pains which seriously affected her life. She was much less enthusiastic. I see patients starting these drugs earlier and earlier, some before they have symptoms. They feel healthy and when they take the drug all of a sudden they have problems.

“My take home message is: don’t trust anyone but the patients. Every-one else is making assumptions. I even include myself in this.

“My take home message is: don’t trust anyone but the patients. Everyone else is making assumptions”

“Fear of side effects or long-term side effects or lasting disability is a luxury for people who have many years left or who have not understood yet that they probably will not be fortunate enough to live to develop these.” Such patients often focus on immediate problems: pain, exhaustion, trouble with walking or with their hands.

The Melanoma Patient Network Europe conference in Brussels in April will focus on risk – including the risk of being over cautious and hindering the introduction of new treatments. “We need drugs for patients not drugs for healthy people,” says Ryll.

But she also sees the risks of adverse events, pointing out that drugs with fewer side effects are more cost-effective as they lead to less waste: “If the side effects become intolerable, people stop taking the drug to give them the space to function, and this becomes more important the longer the treatment. Who wants to be the one who always falls asleep during dinner with friends or at your kid’s school performance?

“Initially, I naively thought all cancer patients took their drugs, but most of our patients have pills left over before they die and these must come from somewhere. Drugs don’t work in patients who don’t take them.”

Patient-collected data

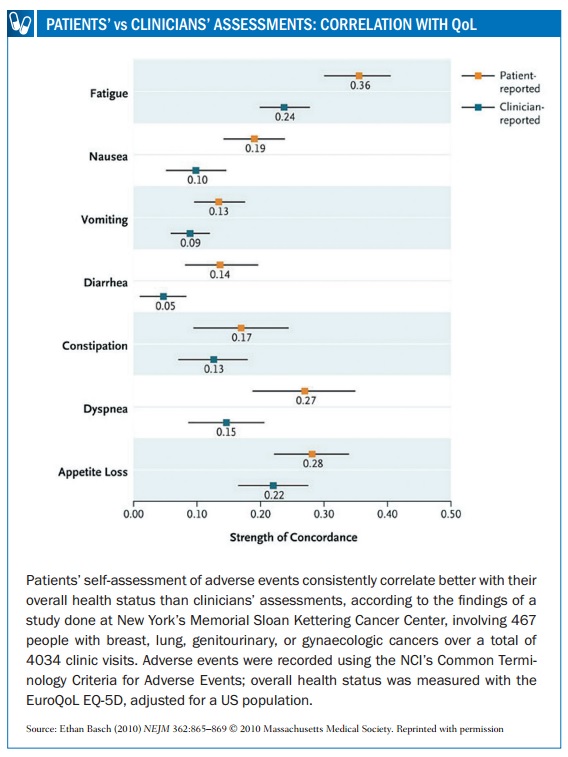

In 2009, a survey conducted by Myeloma Patients Europe (mpeurope.org, then Myeloma Euronet) showed fundamental differences in perception between myeloma patients, nurses and doctors in assessing the impact on quality of life of various side effects, including hair loss, fatigue, reduced body function, neuropathy and thrombotic events (http://tinyurl.com/side-effects-perception-survey). In 2014 an Italian study (Haematologica 2014, 99:788–793) showed that physicians tend to underestimate the impact of fatigue, muscle cramps and musculoskeletal pain, compared to the perception of CML patients.

Ryll’s advice, “don’t trust anyone but the patient” is at the core of advocacy by Susan Love, a former breast cancer surgeon who heads her own research foundation based in Santa Monica. Partly informed by her own treatment for cancer, she is increasingly focused on quality of life issues and “the new normal” after treatment.

“As a physician you compare the patient who is alive to the people who have died and you pat yourself on the back. But as a patient, although you are happy to be alive, you compare yourself to the person you were and are acutely aware of the price you have paid.

“I don’t want to downplay the success of treatment. But we should not act like everything is back to normal and great. We should recognise that in some ways it is like the military coming back from conflict with post-traumatic stress disorder.”

In October 2012 the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation launched the Health of Women Study (healthofwomenstudy.org), as an online cohort study open to healthy women as well as women who have had cancer.

The study has been informed by a collateral damage project which attracted more than 9,000 responses from 3,200 women. By the end of 2014, almost 52,000 women had registered for HOW, of whom approximately 10,000 have had breast cancer.

The quality of life questionnaire (live on the website) asks about exercise, lifestyle, medical history, and environment. The results from women who have had breast cancer treatment and from women who have never had cancer may shed some light on symptoms driven by normal aging and symptoms connected with the cancer or the treatment.

Love says: “The medical profession say all the time that new drugs don’t have side effects like chemotherapy, and that is right – they have different side effects. Herceptin is the poster child of targeted therapies for breast cancer and that certainly has side effects.

“My goal is not to trash the treatments or the drug companies. The purpose is to learn a little bit more about who is getting what so maybe we can avoid it or anticipate it.”

“The purpose is to learn a little bit more about who is getting what so maybe we can avoid it or anticipate it”

This is a study of self-selected women, but Susan Love says that its size irons out any biases. “Most patient-reported outcomes include 100 or 200 people – we have got 10,000. I think we are more representative than the usual patient-reported outcome study in one hospital or medical centre.”

Jan Geissler makes a similar point for the CML Advocates Network. “We recruited 2,500 patients into our adherence study within three months, which is tenfold the number in any adherence study that professionals have done.”

The nurse role in supporting patients

Nurses play a critical role in identifying and treating side effects. Christine Boers-Doets is completing a PhD at Leiden University Medical Centre in the Netherlands, looking especially at skin and oral cavity problems associated with targeted therapies.

“A huge number of cancers are treated with targeted agents, and therapy is discontinued or doses adjusted on a regular basis, even with non-life-threatening side effects. I don’t understand why, as the side effects disappear even if you continue with the therapy. I have learned that it is possible to get rid of them and avoid a grade 3 reaction when patients know how to take care of their skin and mucosa. With appropriate management most adverse events can be managed without dose modification or discontinuation.

“For example, patients need to use an unscented cream from the start of treatment at least twice a day to prevent skin reactions. But they often start treatment too late and are given ointments which do not hydrate sufficiently or lotions which dry out.”

These images show how many different ways targeted drugs can affect the skin, yet medical teams often lack training in awareness and assessment of these toxicities, and the evidence on the specific ways each needs to be treated. More detail about how to assess and manage these sorts of skin toxicities is available in the e-grandround published in Cancer World (March–April 2013) and as a recorded webcast on e-eso.net (Past Programme). Skin toxicities are only one of many troublesome side effects associated with different targeted medicines, which include tiredness, aching bones and muscles, diarrhoea, constipation and other gastrointestinal symptoms, persistent headache, mouth ulcers and more.

These images show how many different ways targeted drugs can affect the skin, yet medical teams often lack training in awareness and assessment of these toxicities, and the evidence on the specific ways each needs to be treated. More detail about how to assess and manage these sorts of skin toxicities is available in the e-grandround published in Cancer World (March–April 2013) and as a recorded webcast on e-eso.net (Past Programme). Skin toxicities are only one of many troublesome side effects associated with different targeted medicines, which include tiredness, aching bones and muscles, diarrhoea, constipation and other gastrointestinal symptoms, persistent headache, mouth ulcers and more.

Boers-Doets developed the TARGET system (Terminology, Assessment, Reporting, Grading, Education, Treatment), to delineate the assessment, grading, and management of dermatologic and mucosal adverse events in a busy clinical setting or research protocols.

“Skin and oral effects can be severe if not treated at an early stage. Chemotherapy can cause a hand-foot syndrome (palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia) while targeted therapy can cause a hand-foot skin reaction. They look the same but require different treatment approaches.

Boers-Doets regrets the lack of clinical trials focused on side effects of targeted cancer treatments, and she has established the IMPAQTT Academy for healthcare professionals and the IMPAQTT Foundation, directly focused on patients and their social support system.

She is developing case studies from her research and by sharing experiences with other specialist nurses. She gives the example of a patient taking Tarceva (erlotinib) for lung cancer, who developed severe and distressing crusts on her scalp, a condition not mentioned in the literature. She discussed treatment with a specialist and the patient’s doctors, and when some nurses attending her lectures said they had also seen scalp crusts, she began developing a case report on the condition and how to treat it.

Boers-Doets says that patients on new therapies need to be seen very regularly at first – perhaps twice a week – until they can manage their own conditions. “Patients go to the pharmacy to pick up their targeted therapies and often stop after a couple of days because of side effects they did not expect. The remaining drugs are discarded. We throw millions of euros away because there is not enough counselling during the first two cycles of therapy.”

“We throw millions of euros away because there is not enough counselling during the first two cycles of therapy”

The nurse role is valued at the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in North Carolina, where Ethan Basch and colleagues work with nurse navigators who advise patients in the clinic and call them at home.

Geissler finds nurses to be a great source of information for CML patients too. “They understand skin rash and gastro-intestinal issues and that has been extremely helpful in how we provide information, so patients and carers can manage it themselves.”

The patient voice is also becoming better heard in clinical research across Europe. The European Medicines Agency finished consulting in November 2014 on a paper calling for quality of life data as perceived by the patient to be included in research protocols, agreeing that “objective clinical measures may not necessarily correlate to a patient’s own feeling of wellbeing.”

Leave a Reply