Every summer a group of top oncologists gather in the ancient city of Ioannina to give a select group of motivated medical students a taste of what its like to work in cancer.

The number of people who develop cancers in greater Europe is expected to grow to 3.4 million a year by 2020, a 20% increase over 2002. Many experts are concerned that the number of cancer specialists will not keep pace.

In 2013, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) pointed out that less than half of European Union countries have good data about the projected numbers of medical oncologists, while the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) highlighted a shortage of skilled radiotherapy staff.

Career choices by medical students is a factor, and lack of specialised undergraduate training has been long recognised. As long ago as 1998 the Deans of medical schools and oncologists from 17 European countries agreed to improve the undergraduate curricula – but the results were patchy.

Andreas Nearchou, aged 31, and now in the final stages of his first residency at Mälar Hospital, in Eskilstuna, Sweden, puts it like this: “People who have not tried chocolate don’t know how it tastes, and if you ask them they may say they are not interested! If medical students are not interested in oncology, I think it is because they don’t get enough information.”

Andreas developed his taste for oncology at one of the very few courses in Europe that allowed students a glimpse of what could be a rewarding career – an intensive week-long Oncology for Medical Students course at the University of Ioannina in northern Greece. Despite the economic crisis, the course has flourished and this July 2014 starts its second decade, attracting students from Europe, the Middle East and further afield.

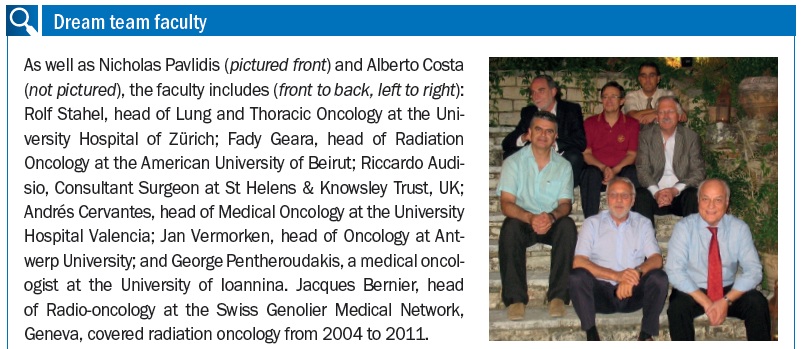

Nicholas Pavlidis, Professor of Medical Oncology at the University of Ioannina, and Alberto Costa, Scientific Director of the European School of Oncology (ESO), developed the course after identifying a profound gap in undergraduate training. Pavlidis says: “We found that in most European universities oncology is not at the top of the training. So we said let’s put together a programme covering almost all of oncology – surgery, radiotherapy and medical oncology – and attract these guys to oncology.”

In 2013 Pavlidis celebrated 10 years at the head of this high-quality faculty with a mission to attract medical students towards the specialism. The €40,000 cost is jointly met by ESO and the ESMO, covering accommodation, registration, meals and books. The student pays only for the travel.

The programme focuses on the common cancers (breast, lung, colorectal, gastric, prostate, head and neck, uterine and ovarian cancer), but also covers “curable tumours” (lymphomas, testicular cancer, paediatric/adolescence oncology and oncogeriatrics).

Each day a faculty member presents a mainstream topic leading to a two-hour discussion on a case study. Each afternoon there is a written one-hour multiple choice exam. At the end of the week, the student who scores highest is offered a month’s fellowship at one of the faculty member institutes.

Each year Pavlidis receives 100 applications from fifth- and sixth-year medical students, for just 40 places. Students do not have to pretend to already be converts. “About 60–70% declare they want to become an oncologist when they apply,” says Pavlidis. “If they are a good student and dedicated, we are open. As long as they have a good cv, good motivation and a good recommendation from their professor, they are going to get in.

“The ones who come are very ambitious. They try to make some contacts among the faculty members that will guarantee their futures.”

Unsurprisingly, the largest number of students – 37 in the first six years – came from Greece, but students have also attended from another 33 European countries, as well as Brazil, Egypt, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Sudan.

Pavlidis said: “Most medical students around the world are aware of this course; it has become very famous. It is amazing to see medical students from Brazil or from India.” More recently there has been an increase in students from the Middle East.

Andreas Nearchou came from Cyprus, and attended in 2007, his penultimate year at the University of Ioannina. He had become interested in oncology through helping a colleague with a meta-analysis of osteosarcoma. “I thought it was quite fascinating, but I was not sure 100%. After I attended the course I was more than sure.”

He did shifts with Pavlidis and the oncology team in his final year, and also helped out with the subsequent student course. “It is a well-organised course with long days. The lectures are very up to date and the staff are a dream team of oncology in Europe. They really know their areas. It showed me that oncology is not a one man show but you work as part of a multidisciplinary team.”

When Nearchou completed his medical degree in 2008, Greece was entering its economic crisis and there were few opportunities in his home country of Cyprus. After an intensive three months studying the language, he applied for a job in Sweden. Much to his surprise – his Swedish was still wobbly – he was awarded a three-month contract, which has since become permanent.

Now 31 years old, he treats a range of cancers at the Mälar Hospital, 110 kilometres west of Stockholm, while working on a PhD in kidney cancers at Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute. He is married to a Greek biologist who also works at the Karolinska, and they intend to stay in Sweden.

Nearchou has recommended the Ioannina course to several Swedish students. “There are only two to three weeks on oncology in the whole degree course, and I think this has to change. In hospitals, 30% of medical treatment cases in are cancer patients.”

The University at Ioannina is only 50 years old, but the welcoming address – on the history of cancer medicine – is delivered in the beautiful 18th century Monastery of Agios Georgios of Dourouti. These have covered oncology in Ancient Greece, Egypt, India and the Renaissance, and Darwinian theory and cancer, among other topics.

Last year was the 10th anniversary course, and amongst all the study, the faculty and students found time for a big celebration, with cake, beach volley ball, eating and dancing.

Over 10 years the course has seen a gradual shift from male to female students. Arpine Gevorgyan, an Armenian student at the University of Milan, was on the first course in 2004, and has noted this trend throughout her specialty. “I have seen it happening but I don’t know why. About 85% of the young oncologists are women and the older generation are men.”

In Ioannina she was especially impressed by the positive attitude towards young doctors. “I knew Pavlidis from his publications and it was really nice to see him organising something for young people who did not even know if they would be oncologists. During the course I became quite sure about my level of preparation and the future.”

Gevorgyan said: “It was a great location and the hospitality was really nice. We had a chance to spend time with the local students and to have fun. For young people it cannot only be about being serious. This is a great course and I would recommend it.”

Pavlidis is starting to research what career paths the students take afterwards – initial findings suggest something like 60% are engaged in oncology. “I do not know if this was a prior decision or was due to the course. We do not have solid evidence yet but will be sending out questionnaires to find out.”

Oncology has not only to attract the brightest, it has to keep them. Gevorgyan, now doing medical research into gastrointestinal cancers at the Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori in Milan and working in public hospitals on solid tumours, feels there is a danger of burn-out. “We are working 18 hours a day and covering Saturday and Sunday. You cannot have your own practice because you are working in a hospital. I will be honest – we are underpaid.

“Oncology is tough because you are constantly working with sick people and you feel you are failing. The research is growing but people still die from cancer, and you cannot do anything about that. You have more failures than successes and it is really depressing, so I am not sure if I will stay in clinical work or go to a pharmaceutical company.”

The challenge of retention underlines the need to recruit. And here too, time takes its toll. Pavlidis is due to retire in 2016. “A few years ago I asked some of the faculty members if someone wanted to take over and they all said that this setting was not achievable in any other European city. When I have to retire I am not sure what is next. Probably one of my colleagues will take over. In 2014 it will definitely remain. It would be a pity to stop it now.”

Leave a Reply