Working lives can be an important part of who we are, and many of us also need to work for financial reasons. Yet cancer survivors often have to struggle to get their working lives back on track. Rights, attitudes and policies could all make a big difference, but so can expectations, preparation and advice. Marc Beishon explores what can be done better to help patients achieve their desired ‘back to work’ endpoint.

There has been an important trend in the cancer advocacy movement in the past few years: a number of cancer survivors who have encountered problems in returning to work have set up or contributed to organisations to help others with work issues. It’s a sign of growing concern about the problem, as many more people of working age are living with cancer and/or the effects of having undergone treatment, due to the combination of cancer becoming a more survivable disease and the age of retirement rising.

Most governments have responded slowly – if at all – with policies that can reduce the difficulties, and many still fail to see the societal picture in terms of the impact of chronic diseases and disability on the economy and society.

Take Isabelle Lebrocquy, a cancer survivor in the Netherlands who has set up Opuce, a social enterprise for cancer survivors that helps find suitable work for job seekers who have recovered from their illness. She lost her own job, working as a manager in the services sector, in 2011, after treatment for colon cancer. “I couldn’t hide that I had cancer – it was an emergency and I had to have surgery – but I was only away for about four months. But I got a text message from the human resources director when I was about to return that said I couldn’t.”

“Healthcare professionals must bear some responsibility for not preparing patients better for survivorship, including work”

This led Lebrocquy to investigate whether she was alone, and she discovered that while Dutch employment law is very generous for full time employees with job security – employers have to pay two years of salary if someone is ill – a lot of people on contracts can fall through gaps. “I did a survey that was completed by about a thousand people that indicated that one in four cancer patients in the Netherlands lose their jobs when they get cancer, and other patient organisations have reported a similar figure. It’s spurred us to talk to employers and the Dutch government to improve matters.”

The number of people who end up leaving their employment after cancer is much higher than 25% – probably 50% or more, as a paper on barriers and facilitators for return to work from the Netherlands notes (Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017, 26:e12420). That’s because there are many who find they cannot perform well enough in their roles, and although an employer may be supportive, they can feel inadequate and leave anyway.

Attitudes in the workplace

That’s what happened to Magali Mertens, who was diagnosed with a salivary gland tumour while working as a communications officer for a non-profit organisation in Belgium. “I loved my job,” she says. “I went back to work about 10 months after my first surgery, but I just didn’t expect effects such as memory loss and fatigue such a long time after. No one told me a lot of patients experience such effects. At first, I had a lot of empathy and attention at work, but after a year my manager said I should ‘get a hold of myself’ – but she didn’t know what I was experiencing. I felt guilty and left. I’m still in contact with her and she does know now that fatigue, especially, is still normal after a year.”

Mertens met a coach – someone who showed her how to become more empowered after cancer. She then trained to become a coach herself, and started her own organisation in Belgium, Travail & Cancer, to work, as Lebrocquy does, with employees and employers on integration plans in the workplace.

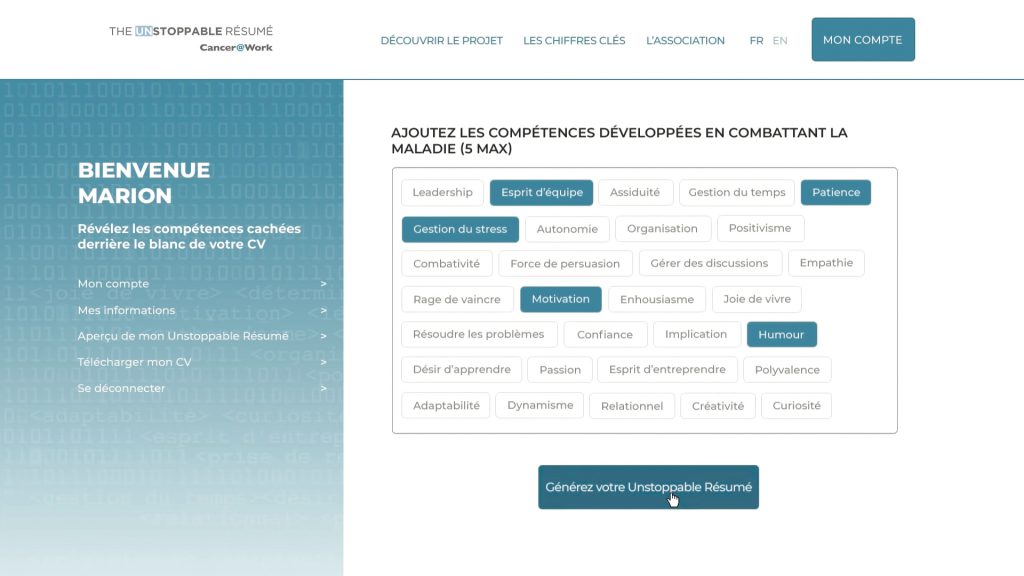

A CV service that works for cancer survivors

The “unstoppable résumé” is a CV generating service developed by the French organisation Cancer@Work, together with LinkedIn, to help survivors trying to re-enter the jobs market. It helps people create a work résumé that ‘tricks’ the digital CV scanning software used by a large proportion of companies, which automatically sifts out people with gaps in their employment history. By using invisible (white) text it fills the gap while also offering users the opportunity to add in up to five positive work and life skills that they feel they have developed while undergoing treatment for cancer. Cancer@Work also offers interview coaching and it works with a growing number of employers to provide advice and education to human resources departments and offer a job ‘dating agency’ aimed specifically at cancer survivors. At a wider societal level, the organisation works to challenge attitudes and assumptions about what cancer survivors can offer at work.

Cancer@Work was set up and developed in the context of a strong national policy supporting the rights of cancer patients to stay in work or return to work after treatment ‒ an issue that was highlighted in the 2009‒2013 French national cancer plan.

Healthcare professionals must bear some responsibility for not preparing patients better for survivorship issues, including work, says Liz O’Riordan, who has sat on both sides of the table – as a breast cancer surgeon in the UK National Health Service (NHS) and then a breast cancer patient herself. “As doctors, we are so busy explaining diagnoses and treatments that a lot of life problems for patients are just not on our radar,” she says. Talking of her own experience as a patient, she says that she was initially off work for 18 months, and then tried to negotiate a phased return to work, not working full time at first, as she just did not have her previous energy. “But I was only offered one month for a phased return – and I just didn’t know my rights, that I was entitled to more time.”

Her hospital did though keep her stand-in surgeon on, but as she says: “I was very aware that if I couldn’t make it work I would have to retire. As a super-specialised surgeon I couldn’t think realistically about retraining, say as a GP, as that would take years.” A recurrence of the cancer then forced retirement. In the meantime, however, O’Riordan had met Barbara Wilson, who runs the UK group Working With Cancer, who helped her cope with both the physical and psychological aspects of survivorship. She has since joined Wilson’s team as an advocate, with workplace issues as part of her interests.

O’Riordan appreciates how important work can be as an escape route for people to feel normal and maintain a sense of purpose both after cancer and during treatment. A case in point: when working as a surgeon, she was treating a young woman with learning disabilities. “I told her that she needed chemotherapy and that people don’t usually work during the treatment she was to receive, but she burst into tears and I couldn’t work out why. Then one of the nurses told me that work got her out of the house and gave her purpose – and I had told her she can’t work.”

The opportunity to continue life as normal is emphasised by all three advocates, with work often a central part of activity, although it can also be a financial necessity. While fatigue is a common long-lasting effect of cancer treatment, even among those who are considered cured, there are many other effects, which may depend on the type of cancer and its treatment, and which can also influence how colleagues in the workplace view someone who has returned.

As O’Riordan notes, many women who have had breast cancer will have had surgery and radiotherapy but no chemotherapy, so will not lose their hair, which is a stereotypical view that people often have about cancer treatment. “So they mostly look normal to others, but can be experiencing low energy, stress and also psychological problems. People with other cancers may need more obvious accommodations, such those who have had a colostomy after colorectal cancer.” She mentions too a nurse who had breast cancer but had to wear an arm sleeve to counter the effects of lymphoedema – but NHS policy is ‘bare arms’.

It may never be possible to get back to what was ‘normal’ before, and there is often no linear path of improvement, but good and bad periods

It may never be possible to get back to what was ‘normal’ before, and there is often no linear path of improvement, but good and bad periods (and people with metastatic disease may be moving in and out of treatment cycles over some time). What people who have had, or still have, cancer want is choice about how and whether to work given uncertainties, and they need employers who have information about the nature of cancer and its long-lasting effects.

As O’Riordan stresses, they also need healthcare and social care professionals who can provide information about long-term effects and rights, in addition to the more immediate treatment-related issues. “I would like to see people told about the rights available to them in any country when they start a job,” she says. “When you’re diagnosed you’re caught up with your treatment, as I was, and I knew next to nothing about my rights or those of others when I was working as a surgeon.”

A point made by both Lebrocquy and Mertens is about the type of work involved. It can be much easier to make accommodation for someone returning to an office role than those with jobs that involve manual tasks such as truck driving and delivering mail. They may not have the physical capabilities to continue in these jobs and are more likely to be made redundant. This challenges society and employers to help people retrain and find new types of job, says Lebrocquy, whose organisation acts as a ‘matchmaker’ for finding suitable roles – which can take months.

Another point made by both advocates is that people returning to work after cancer can have a different outlook on life, having had a serious illness. They can be determined to live life to the full (but possibly try too hard) and can give much back to an organisation in terms of ‘soft skills’ of a positive outlook, and time and stress management, which is where coaching is valuable.

While legal recourse to return to work varies around Europe, there is nothing to stop organisations implementing good practice, and Lebrocquy highlights electronics giant Philips in the Netherlands as an exemplar. The company runs an employment scheme that includes placing people with occupational disabilities, and which since 2013 has accommodated cancer survivors.

Towards a European strategy

The European Cancer Patient Coalition (ECPC) has a new director, Antonella Cardone, with a particular interest in work issues, as she moved there from running the Fit for Work Global Alliance, led by the UK’s Work Foundation. She says one of the biggest problems is still the stigma of cancer, and the view that patients are often just not expected to return to work. But in recent years some countries have established best practice backed by legislation that allows people to work part time for extended periods, for example. There is no pan-European strategy, however, which is why ECPC included a call for one in a manifesto issued ahead of the 2019 elections to the European Parliament. Workers with cancer should be protected from dismissal and there is a need to better understand the living conditions of cancer survivors who return to work.

“There is no pan-European strategy on survivorship, not just about work, and there is huge disparity among countries,” says Cardone. In some eastern European countries, survivors get very little protection, if any, while countries such as France, Italy and the UK have extensive rights. “But if countries invest in protection there can be great economic gain in both the employment and welfare sectors, as people stay on at work rather than retiring early, taking pensions and putting extra burdens on welfare systems.” People forced into inactivity often develop comorbidities, she points out, and with the rising retirement age, taking increasing numbers of people out of the workforce can have a double impact of lower productivity and higher health and social care costs.

“We know that healthcare spending is becoming increasingly unsustainable in Europe, so we need to find ways of balancing this with return on investment in other sectors. But a big obstacle is the ‘silos’ that ministries often work in,” she says, and she argues for much greater cooperation between departments responsible for health, labour, economy and welfare, in particular. The economic impact of other conditions, such as musculoskeletal disorders, have been studied more than cancer, she adds. The ECPC manifesto calls for urgent action to address this knowledge gap – along with other survivorship issues such research on late effects, social rights (eg access to financial services), and implementation of the EU’s Work–Life Balance Directive, which includes more rights for carers, who are a critical and largely unpaid workforce.

A number of members of the European Parliament have taken an interest in survivorship issues. Among them is Lieve Wierinck, a Belgian MEP who hosted a meeting on the topic with the Advanced Breast Cancer (ABC) Global Alliance, in 2018, entitled ‘I have cancer but I want to work – working rights of cancer patients’. Wierinck has herself been treated for colorectal cancer, including six months of chemotherapy. She said that quality of life is strongly impacted by cancer, and that she was happy to go to work for the distraction of focusing on something else. It is crucial to address disparities and harmonise standards for all Europeans she said, and she has since promoted the idea of a European cancer plan.

Wierinck emphasised that financial support is crucial to enabling flexibility for employers that find it hard to support unpredictable patterns of absence for cancer patients. What would help – and break down ‘silos’ – is replacement income from the welfare budget that switches in on days when an employee cannot work.

A report from the European Parliament, on pathways for the reintegration of workers recovering from injury and illness, now includes amendments on cancer, and in 2018, a group of MEPs led by Rory Palmer (UK), launched the European Dying to Work campaign, which aims to protect terminally ill workers from dismissal. As it stands, there are no specific protections for terminally ill employees. The campaign, which originated in the UK, “notes with concern the cases of the unfair dismissal or treatment of terminally ill employees. We are calling for the introduction of EU legislation to safeguard the rights of employees by identifying terminal illness as a protected characteristic.”

Karen Benn, Deputy CEO and head of policy and public affairs at Europa Donna, the European Breast Cancer Coalition, says the EU’s Employment Equality Framework Directive 2000 is the legislative framework that should protect people with both early and advanced cancer from discrimination. This directive prohibits discrimination on the grounds of disability, sexual orientation, religion or age, and cancer can be considered to be a disability. But it is a directive and not a regulation, and while it must go onto the statutes of the EU member states, each country has the flexibility to define what constitutes disability, and whether cancer fits their definition. The directive requires employers to make “reasonable accommodation” for the working environment for all employees, but must not cause the employer “disproportionate burden”.

“What would help is replacement income from the welfare budget that switches in on days when an employee cannot work”

Some states, such as the Nordic countries, Netherlands, Ireland, France, Belgium and the UK, do give cancer patients the option to register as disabled and benefit from this legislation for their working rights, among other things. In Italy and France people can also register as disabled for a certain period of time and then ‘unregister’ themselves – as not everyone wants to be defined as disabled for the rest of their lives. However, in many European countries, formal protection is either non-existent or legally ambiguous, and there is no data on how many cancer patients return to work or how easy they find it to do so.

There are also big disparities in how countries help people return to work after long-term illness. The Scandinavian countries are good, says Benn, offering every cancer survivor a return to work plan. There is an opportunity for national cancer plans to address employment as part of survivorship; this is already happening in the UK and France, and has been proposed in the European multistakeholder reports which resulted from the EU joint action projects such as the CanCon Joint Action (see opposite). But even in the more advanced countries, there is little provision for the growing numbers of people who are self-employed or who work on short-term or ‘zero hours’ contracts (where employees are essentially ‘on call’).

It’s about policies and plans

The European Guide on Quality Improvement in Comprehensive Cancer Control, developed by the CanCon European Joint Action, calls for national cancer plans to include policies to support cancer patients from diagnosis to return to work.

It also advocates for a pan-European strategy to tackle the differences between workers with cancer in different countries and to prevent discrimination, and argues for generation of more evidence to better understand the living conditions of cancer survivors who return to work. It offers detailed policy recommendations for quality improvement in cancer after-care at the community level and in cancer survivorship and rehabilitation.

In its manifesto issued before the European Parliament elections in 2019, the European Cancer Patient Coalition called for member states to implement the CanCon recommendations. They also called for adequate funds for research on survivorship to generate data on late effects, as well as on the impact and cost-effectiveness of supportive care, rehabilitation, and palliative and psychosocial interventions.

The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (OSHA) has produced a report and advice for employers on reintegrating workers with cancer in the workplace. The report, ‘Rehabilitation and return to work after cancer: instruments and practices’, identifies good practice in countries such as the Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands and the UK, and includes case studies and focus group reports, and also a literature review of the health and economic impacts, and interventions.

France has taken a lead in developing and implementing policies supporting patients who want to work during and/or after cancer. This issue was highlighted in the 2009‒2013 French national cancer plan, which made resources available for initiatives and projects, and created conditions for the development of organisations such as Cancer@Work (see “A CV service that works for cancer survivors”).

In eastern Europe, as an article in Cancer World recently detailed (Spring 2019), the focus is still on hospital-based services, and much less on outpatient and survivorship programmes. For example, a recent paper on return to work policies for cancer survivors in Romania reports that while there is a strong focus on compensation, with paid sick leave and access to pension and disability benefits, “for several components of return to work, only the general principles are stated, e.g., the need for work adjustments or the importance of stakeholders’ communication, yet the procedures to put these general principles into practice are not specified… the law reflects the low awareness of cancer survivorship as related to work issues,” (Disabil Rehabil 2019, 24:1–8).

In another paper, the authors say that employers need information and guidelines for assisting employees with cancer, and “better channels of communication and collaboration with health professionals are essential for more adequate support for the long-term consequences of cancer. A detailed return to work policy is required to tackle the inconsistencies in the support offered, and this policy must also rethink how diagnosis disclosure takes place in Romanian organisations” (J Occup Rehabil 2019, July 11 doi: 10.1007/s10926-019-09846-1).

At European level, a number of other organisations are looking at cancer and work. Foremost is EU-OSHA, the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, which has produced a report and advice for employers on reintegrating workers with cancer in the workplace (see above).

Eurofound, the EU agency for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, has looked at cancer in the workplace. EPF, the European Patients’ Forum, has also focused on patients’ rights in the workplace and protecting those living with chronic illness from workplace discrimination. There are also reports by the Economist Intelligence Unit, ‘Cancer in the workplace’ and ‘The road to a better normal: Breast cancer patients and survivors in the EU workforce’, both of which contain detail on obstacles and strategies to overcome them.

So there is much information about what ‘good’ looks like in employment practice for cancer survivors and a growing clinical literature base on the physical and psychological effects that survivors experience. What’s missing is data on how many people are affected around Europe – and the joined-up strategies that can help them.

Leave a Reply