Results from studies on PARP inhibitors show that BRCA status and responsiveness to platinum analogues are much less binding that it was thought to achieve some improvements. But more clinical trials are needed to decide if PARP inhibitors should be used as part of first-line therapy or reserved for a later line

Things are finally moving in the field of ovarian cancer treatment. After bevacizumab, other targeted therapies start to achieve results in this challenging field, too. Not a revolution, yet, but a significant progress, and less grim perspectives than they used to be in a recent past. Because of lack of early symptoms and effective tools of screening, in fact, serious epithelial ovarian cancer – the most common type of this uncommon disease – is often diagnosed when it is already advanced. Despite great efforts in research, improvements have been slower than towards other tumours so far, and the disease is still hard to cure: even if most patients do respond to surgery and initial chemotherapy, 7 out of ten of them eventually relapse and die.

Therefore, the question is: what to do after this first phase? When the response to platinum-based chemotherapy is good, sensitivity can last, and, in case of recurrences, up to 3, or sometimes even 4 series of treatments can be repeated. However, after that, although the tumour does not become resistant, toxic effects on the patients cannot usually be managed anymore.

The Achilles’ heel of ovarian cancer

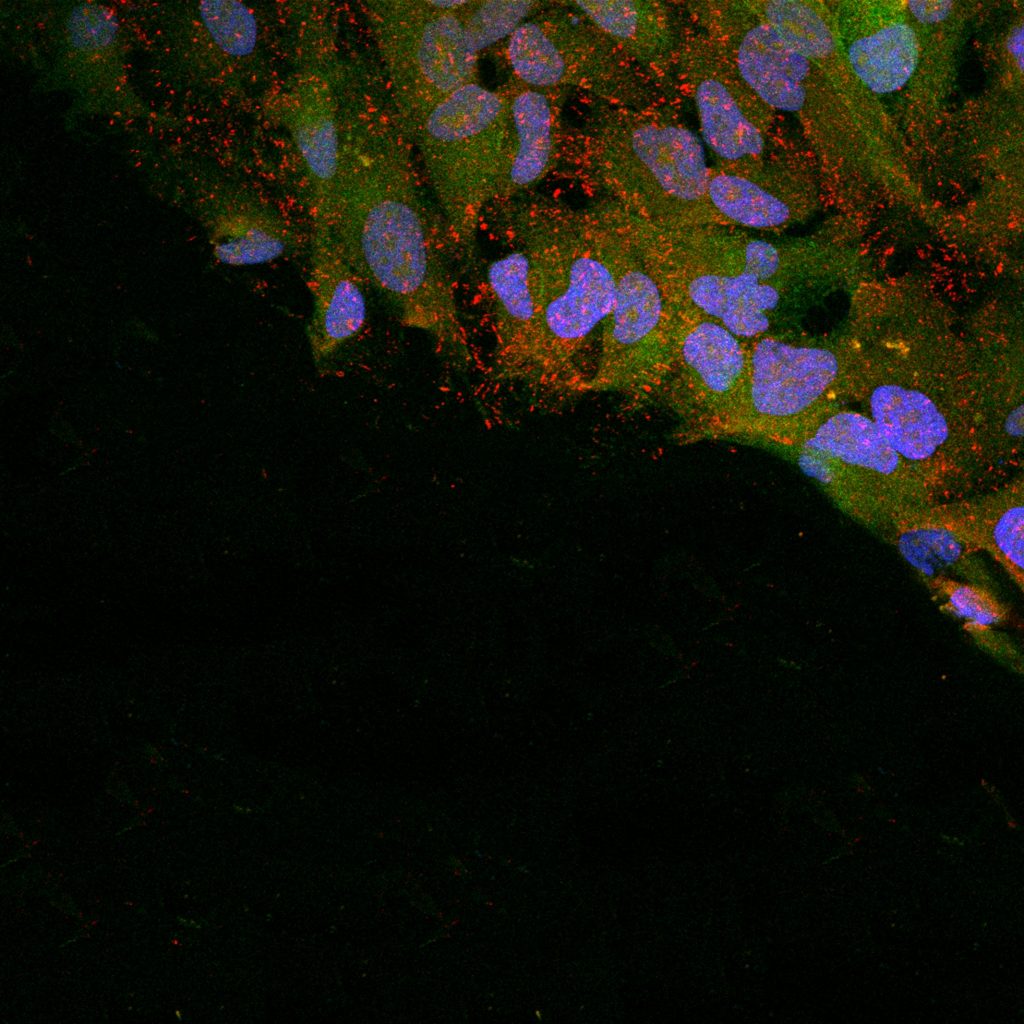

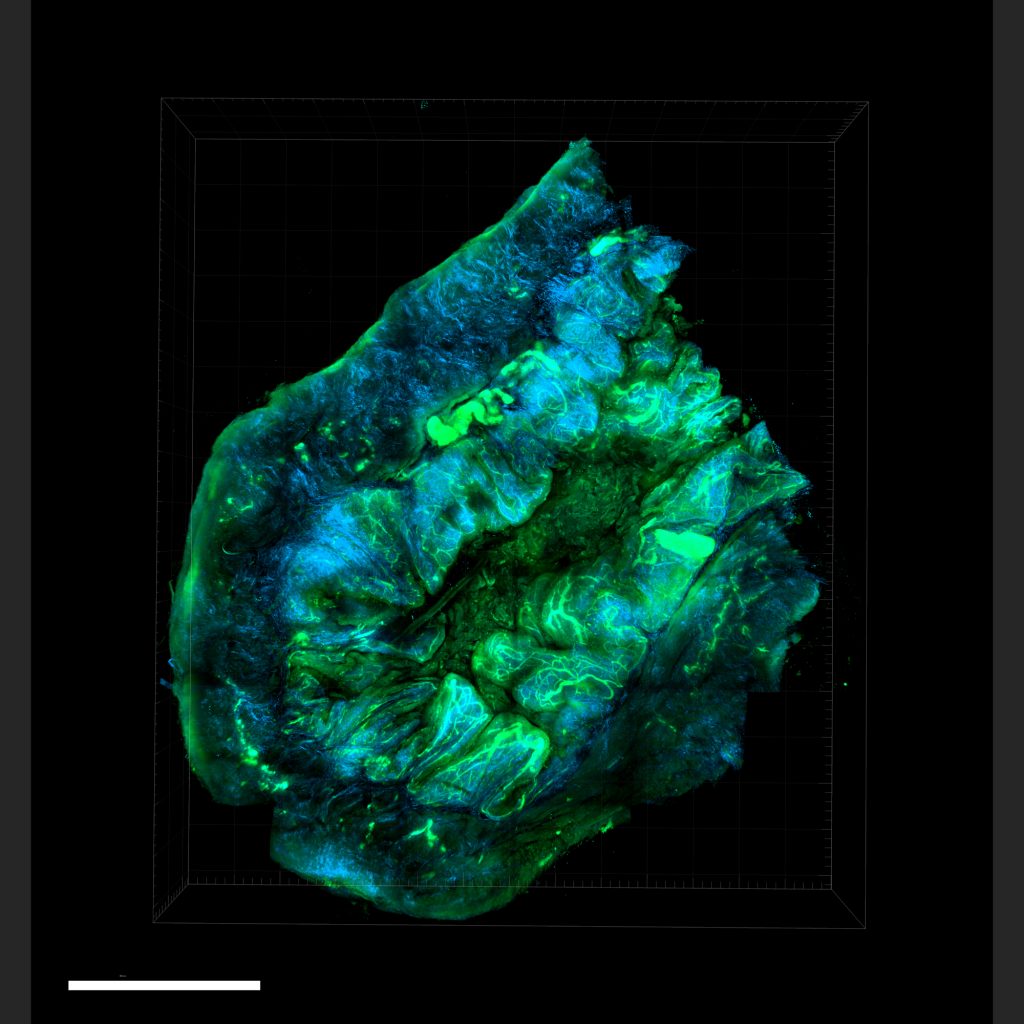

In order to face this challenge, researchers have thought to exploit the main weakness of this cancer identified to date, which is its scarce ability to repair DNA damage in its cells. This vulnerability is exploited by PARP-inhibitors, oral, well-tolerated drugs that disrupt the cell machinery needed for this job. They are particularly effective when other mending mechanisms are impaired, as happens in tumours harbouring a deficiency in homologous recombination repair (HRD), such as mutations in BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 genes. BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants can be inherited and already be present in germinal cells. In this case, they strongly increase the risk of breast cancer in addition to ovarian cancer. Otherwise, they can result from new mutations occurring within the tumour. In both cases, the presence of BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations is a hallmark that predicts better efficacy of PARP-inhibitors.

Three drugs of this class have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in patients with high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer – including disease rising in fallopian tubes or detected in the peritoneum: olaparib, niraparib and rucaparib. They can be given as maintenance treatment, when platinum-based chemotherapy has reduced or cleared the cancer, in order to try to keep it from returning after one or two relapses.

Following the results of SOLO-1 study, which showed greater and sustained progression-free survival at 3 years with olaparib versus placebo (60% vs 27%), FDA and EMA approved this drug also after the first line of chemotherapy, in newly diagnosed women with advanced cancer, but only if they responded to platinum analogues and have BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations.

A broader range of effectiveness

The good news, coming from a new study published on the Lancet Oncology in spring 2019 (Lancet Oncology Vol 20, Issue 5, P636-648, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30029-4), is that both BRCA status and responsiveness to platinum analogues are much less binding that it was thought.

In the QUADRA study, in fact, a daily tablet with 300 mg of niraparib was associated with a median overall survival of more than 17 months in 463 patients previously treated with three or more chemotherapy regimens, both BRCA-mutated and not, with HRD-positive and HRD-negative tumours. This is very important because only 1 out of 5 patients with ovarian cancer have a BRCA mutation.

Women with primary or acquired platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory high-grade ovarian cancer were included. “Our work showed that niraparib has clinical activity in patients across the spectrum of biomarkers and sensitivity to chemotherapy,” says Kathleen Moore, from the Stephenson Cancer Center at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, in Oklahoma City, first author of the study.

This broad population, enrolled in 50 centres in USA and Canada, is reflective of real-world patients with late-line ovarian cancer, for whom all effective treatment options have often been exhausted. “This finding is very encouraging, as 58% of patients in QUADRA study had previously received four or more lines of chemotherapy,” comments on the same issue of the journal (Lancet Oncology Vol 20, Issue 5, P603-605 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30087-7) Claudia Marchetti, from Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli, in Rome.“Previous data found a median overall survival expectation of 10,6 months in this heavily pre-treated population”.

Subgroups with different response

BRCA mutations and platinum sensitivity have not lost their meaning yet, anyway:almost 40% of patients with both of these characteristics responded to the treatment with a tumor reduction by more than 30%, while the proportion decreased to 27% in platinum-resistant or refractory women. And, even in women who had showed platinum-sensitivity at the last chemotherapy, the overall response rate dropped to 4% if HRD state was negative or unknown.

“BRCA testing still remains very important in triaging therapies for patients. Knowledge that a patient has one of these mutations would prioritize PARP-inhibitors over other options, in this setting of fourth line and beyond” Moore explains. “Our results don’t diminish the importance of BRCA testing, they just expand the indication beyond BRCA positive patients to a population who are still considered eligible for platinum and have homologous recombination deficiency”.

So, this work shouldn’t be misunderstood. It does not represent a U-turning point towards a one-fits-all treatment approach, after years of precision medicine. On the contrary, its results claim for the search of new markers for identifying subgroups with longer survival.

In fact, in a subgroup analysis of QUADRA study, a median survival of 28 months has been demonstrated in women who had showed a clinical benefit for 24 weeks or more taking their daily tablet, regardless of their BRCA mutation status and of the type of response: some had only stable disease, while other got partial or complete response. Duration of response could therefore be very relevant in prognosis.

Treatment, not only maintenance

“This group of patients, who account for around 20–25% of the entire patient population, could achieve an extraordinary survival improvement with niraparib treatment in the late phase of disease, even in the absence of a reduction in tumour size,” adds Marchetti. “Unfortunately, this set of patients remains unidentifiable, and neither BRCA or HRD status nor platinum sensitivity have helped in their identification in this and other trials”.

“The search of new biomarker is essential,” Moore adds. “Certainly BRCA is a proven biomarker for selecting patients who would benefit from PARP inhibitors. HRD has been helpful, but not definitive, in the recurrent platinum sensitive maintenance setting. QUADRA suggests HRD is important in identifying a subgroup of patients who would benefit from monotherapy niraparib for treatment, not maintenance. This is important because, if these patients did not receive a PARP inhibitor as a part of a platinum sensitive maintenance regimen, there is no other setting currently where they can access such a drug for treatment. The QUADRA population may open that up”.

“More biomarkers are needed to improve signature characterisation, both for patients who will unequivocally benefit the most and have to receive niraparib during their disease course, but also for those who are not showing a substantial clinical benefit and for whom overall survival remains disappointing. This latter group of patients should be involved in other well-designed clinical trials so that they can obtain similar improvements,” adds Marchetti.

This could spare side effects not counterbalanced by benefits in not responsive patients, but also cut costs. When talking about innovative drugs, in fact, financial sustainability of the treatment is always at stake.

“The cost for the drug is still very high” Moore admits “but the subgroup of HRD positive patients eligible for the treatment, who benefitted from niraparib, did so for 9 months, which is very clinically relevant. Therefore, the costs may balance out as opposed to use of an expensive drug or expensive testing for a 3 months progression-free survival (PFS), for example”.

Relevant endpoint from a patient’s point of view

From a patient’s point of view, shrinking the tumour is not the only, or most important, parameter of success, if this means being frustrated at next scan when discovering it grows again. Getting a longer interval between relapses, being able to spend more time at home than in hospital, taking just one daily tablet with affordable side effects, are much more relevant outcomes. That is why duration of response and disease stabilisation, rather than the proportion of patients achieving a response, has recently been suggested as a better outcome to consider.

“These are incredibly important clinical endpoints, especially in women with many prior lines of therapy,” says Moore. –“Disease stabilization with good quality of life for a clinically meaningful period of time is a key achievement in treatment. Of course, we want our patients to respond, but lack of growth for many months with good tolerance of a therapy can be just as meaningful. It is just a difficult endpoint to standardize from a regulatory standpoint and so, it is not considered in that setting, when it comes to approval by FDA and EMA”.

Don’t claim victory just yet

“The survival reported in QUADRA of patients receiving several lines of prior therapy is meaningful but is important to note that QUADRA is a single arm study with response rate as the primary endpoint” points out Susana Banerjee, Consultant Medical Oncologist and Research Lead for the Gynaecology Unit at the Royal Marsden and Institute of Cancer Research, in London. “The fact that PARP inhibitors have shown activity as a later line treatment in ovarian cancer patients irrespective of BRCA status is certainly very encouraging, but we need the results of randomized controlled clinical trials to draw further conclusions”.

Another critical point is that these results refer to patients never treated with PARP inhibitors before, and we do not know how and when drug resistance could develop. “The key question is where PARP inhibitors best fit in the overall treatment pathway: should they be used as part of first line therapy or reserved for a later line, for example in the maintenance or treatment setting? These are issues that need to be addressed in well designed clinical trials,” adds Banerjee, who is also member of the ESMO (European Society for Medical Oncology) council.

Work in progress

At a slow pace, anyway, survival is improving also in this deadly disease. “Wedemonstrated improved survival based on increased prevalence of women living with ovarian cancer in both the US and Europe, despite no change in incidence or mortality” says Moore. “That means that our supportive care and therapies at time of recurrence are pushing out overall survival. But we want also to improve disease free overall survival and that will take improvement in either screening or front line therapy. SOLO-1 may demonstrate an improved overall survival among BRCA associated cancers, but we will have to wait several years for that read out”.

We still need a lot of research in screening strategies, biomarker signatures, choice and timing of each treatment, but, at last, we can nurse a hope.

Leave a Reply