Not all clinicians choose to look beyond doing their best for their patients to learn about the science behind the disease and play a role in progressing treatments. Fewer still are the successful clinician scientists who choose to look beyond that work to help shape an environment in which medical research and education can thrive.

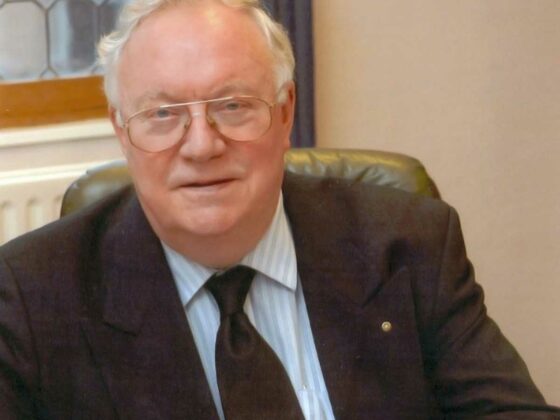

Michael Peckham, who died on August 13 2021, was a one such. He made his name in the early 1970s, working at the UK’s Institute of Cancer Research/Royal Marsden Hospital, in particular for his contribution to progress in treating Hodgkin lymphoma and testicular cancer.

He went on to play a major role in shaping the professional, clinical research and educational life of what was then an emerging multidisciplinary specialism.

His influence was all the greater because of his strong European outlook – and fluency in European languages – both of which were rare among British medical professionals in those days. Also important was a deeply rooted antipathy to artificial boundaries and silos. Torn from an early age between building a life in the arts or medicine, even after qualifying as a medic, Peckham faced real doubts about the choice he had made.

While opting in the end for a career in oncology, he never gave up his interest in art and painting, and he brought both creative and scientific intelligence to his oncology work, examining problems from multiple perspectives, looking for underlying patterns and seeking to make connections. ‘If you’re an artist you have to take the holistic view,’ he once commented in an article in the New Scientist, adding “I think it’s prevented me from retreating into ultraspecialist activities.” In a 2018 article for the Lancet, Art and Oncology: One Life, he described the images in his 2013 exhibition, Philomena, as derived from “notions of concealment, detection, and metamorphosis”, which ‒ together with the physical violation at the heart of the Greek myth ‒ might be considered a neat summary of cancer and oncology.

An exciting start

A two-year UK Medical Research Council fellowship gave him an enviable start to his career at the Department of Radiation Therapy at the Institut Gustave Roussy, in Paris, working under Maurice Tubiana – a towering figure in the vibrant French oncology scene.

This was 1965. For a young man interested in the ‘big picture’, Paris was a hugely stimulating place to be. In his Lancet article, Peckham remembered that time as “an exciting period in art, medicine, and politics ‒ just before the student riots of 1968,” and he frequently referred to it as a highly formative experience.

Tubiana’s laboratory was very much part of those exciting times, leading efforts to develop a more sophisticated approach to radiation therapy, based on an alliance and partnership between clinical medicine, physics, and radiobiology.

Hodgkin lymphoma was a major focus. Radiation techniques had been evolved aimed at curing the disease. Tubiana was leading translational and clinical work to develop treatment protocols tailored to specific prognostic factors, to maximise chances of a cure while limiting unnecessary collateral damage.

Returning to the UK in 1967, Peckham joined the Institute of Cancer Research/Royal Marsden Hospital, and was given a chair in 1973 becoming Professor of Radiotherapy.

Over the 12 years in that post, Peckham’s unit kept up a prolific publication rate. He continued the work in lymphoma he had first encountered under Tubiana, including developing the scientific rationale and clinical evidence for mantle-field radiation. The technique aimed to reduce recurrence by extending the radiation field beyond the major lymph node areas that contained lymphoma, to also include the surrounding apparently ‘normal’ lymph nodes, to pick up undetected cancer cells. This became a new standard of care at the time, though it was later overtaken by progress in medical treatments for lymphoma.

He also led work in the management of testicular cancer, exploring issues in the sequencing of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and developing a novel platinum-based combination treatment for testicular cancer. A study published by his unit in 1983 showed that, in advanced testicular cancers, the BEP protocol, which used bleomycin, etoposide and cis-platin, retained the impressive cure rate associated with the then standard of care – cis-platin, vinblastine and bleomycin (PVB) – while reducing the complications caused by very high toxicity.

A champion of multidisciplinary care

Peckham started his career at a time when treatment of solid tumours was chiefly the preserve of surgeons and radiotherapists. Medical oncology – chemotherapy and some hormonal therapies – was just beginning to establish its role alongside other modalities as part of a curative approach. While some countries saw medical oncology as a subspeciality of internal medicine, in the UK (and some other countries) the specialism was combined with radiotherapy in the role of clinical oncologist.

Much of the work done by Peckham’s unit at the Institute of Cancer Research involved learning how to combine both modalities to greatest effect, and he understood early on, the importance of shaping oncology training and research, and the delivery of cancer care, around truly multidisciplinary principles.

He actively promoted this approach, participating in discussions on who should treat cancer, which took place in 1981 in the pages of the Lancet. And when necessary, he did not pull his punches, as in a letter to the Editor that he co-wrote in response to a Lancet editorial that purported to sum up the discussion in its pages. “The statement that most surgeons and gynaecologists have already become expert in the use of modern cytotoxic chemotherapy is clearly untrue,” wrote Peckham, adding “… It is a dangerous muddying of the waters to imagine that all we really need are a few gynaecologists, surgeons, or haematologists who, despite no real training in cancer chemotherapy, will rapidly develop expertise through experience. This is in the worst traditions of British amateurishness, and ought to be roundly condemned.”

A European

Similar arguments were being played out at the time all across Europe, and Peckham saw the value of linking up to give a stronger voice to oncology professionals.

In 1980, the year before that discussion in the Lancet, Peckham had got together with his former mentor, Maurice Tubiana, and three other leading lights in European radiotherapy, to found the European Society of Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO – now the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology). And the following year he co-founded, and became the first Chairman of the Federation of European Cancer Societies (FECS). Now evolved into European Cancer Organisation, FECS represented a highly significant milestone in shifting cancer medicine towards a multidisciplinary approach, bringing radiation oncologists (ESTRO) together with the medical oncologists (ESMO), the cancer surgeons (ESSO), and cancer researchers (EACR).

In 1982 he followed up this pan-European multidisciplinary approach by teaming up with some of the top names in European cancer surgery and medical oncology to co-found the European School of Oncology. The organisation aimed to fill a growing gap between the rapidly developing cutting edge of multidisciplinary cancer practice and the education and training young medics were receiving in relation to cancer. It also sought to promote what it saw as a distinct ‘European’ approach to cancer care, which Peckham argued was more holistic and gentle than the approach taken in the US, where he felt chemotherapy was often overused in dying patients.

An ‘unlikely civil servant’

While all this was going on, Peckham was still highly involved in his clinical research role. The results of the study comparing BEP against PBV in advanced testicular cancer, for instance, were not published until 1983.

Yet his focus was clearly shifting towards the bigger picture of creating an environment and structures at the level of education, research and delivery of care, where oncology and medicine in general could flourish.

In 1986 he took up a post as Director of the British Postgraduate Medical Federation, a school of the University of London comprising seven postgraduate medical institutes.

When in 1991 the National Health Service (NHS) launched its own Research and Development programme, Peckham was appointed as its first Director. He oversaw the development of clinical research effort that became widely admired across Europe for its ability to plan and coordinate clinical research to address priorities for patient care. The programme also provided funds to set up the Cochrane Centre to facilitate systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials across all areas of healthcare.

Peckham continued to focus on the big picture policy areas for the rest of his career, including in his role as Director of the School of Public Policy at University College London between 1997 and 2000, and as chair of the UK’s National Educational Research Forum, established in 2000.

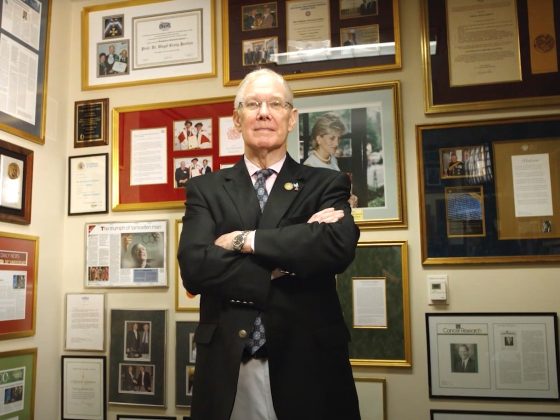

‘An unlikely civil servant’, is how the New Scientist referred to Peckham in a 1991 profile piece, written after his appointment to head up the NHS Research and programme. “There are not many senior medical researchers in Britain who would list the political upheavals of Paris in 1968 among their formative experiences. There are fewer who read Czech poetry, or have their paintings exhibited regularly in London and Edinburgh. But Michael Peckham does all three,” it commented.

The point was well made, in that Peckham, creative, goal-oriented, with impressive experience in the field, and not afraid to confront vested interests, was in many ways the opposite of a stereotypical civil servant.

Yet in its true sense, Peckham really was a civil servant – he served citizens. True to his early instincts, he refused to limit himself to doing the best he could for his patients, or even to contributing hands-on to improving standards of care. He always kept his eye on the bigger picture – on what medicine was trying to achieve, and on the environment that shaped what was possible. Along with a small number of visionaries at that time, he led efforts to reshape the way the rapidly changing field of oncology – and medicine as a whole ‒ was taught, researched and delivered.

Given the still escalating complexity, not to mention cost, of cancer research and treatment today, ‘unlikely civil servants’ like Peckham are arguably needed today more than ever.