When it all started, Ioana Oprea did not have a spare moment to come to terms with what had happened ‒ to truly take in the fact that her son Teodor had a brain tumour. In the autumn of 2020, she urgently had to find a suitable treatment centre for the six-year-old in Bucharest, and then she had to support him for months during his chemotherapy and radiotherapy. And although the treatment went well, she still couldn’t relax. Oprea learned that the boy needed a particular drug to prevent the tumour from growing again ‒ a drug that could not be found in Romania. “I immediately started looking for it,” says the mother.

That was in June 2021. By the end of September, Oprea was sitting in the bright offices of the Magic association, showing photos of Teodor on her cell phone ‒ a slim boy with large dark glasses who is now much better. It was in this exact spot, in this pale-green building with children’s handprints decorating the facade, that she finally received the medication that her son so urgently needed.

To help cancer patients like Teodor, the Bucharest-based association set up an international network of volunteers seven years ago, to bring medicines to Romania ‒ from Austria and Germany, for example, from Hungary and France, from Great Britain and Bulgaria. At the beginning of the pandemic, the staff even created a website where patients, relatives, or doctors can contact them directly if they are looking for a specific medicine. “As long as we get a prescription from the patients, we can get the medication anywhere in the EU,” explains Adriana Andrei, project manager at Magic. On average, they receive ten enquiries a day. In this year alone, the association has helped almost 2,000 patients.

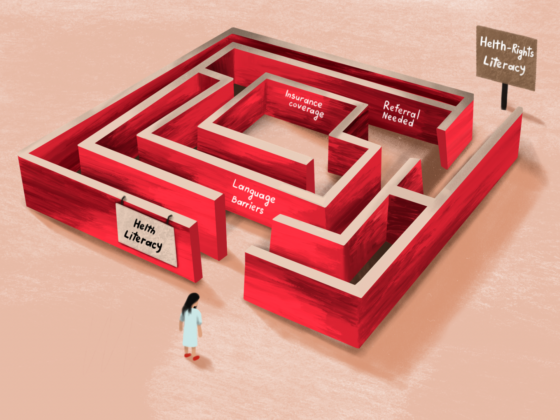

The lack of access to essential healthcare products that led to a worldwide outcry during the current pandemic, in relation to vaccines, has long been a reality in Romania. Here, in the middle of the EU ‒ not the developing world ‒ some essential medicines have been unavailable for years. The only analysis of missing cancer drugs in Romania, published by the Romanian Health Observatory in 2018, showed that 24 of 113 drugs were not available, and a further 13 were showing signs of shortages.

From 2015 to 2017, the Agency received 2,600 notifications of unavailable medications, most of them for the treatment of cancer

From 2015 to 2017, the National Medicines Agency received 2,600 notifications of unavailable medications, most of them for the treatment of cancer. As a European report showed, the drugs were unavailable in Romania for an average of 6.5 months; the cancer drug bleomycin was unavailable for a full two years.

For Teodor too, things initially looked bad. The only Bulgarian pharmacist in the international network did not have the cancer therapy ready, neither did a Hungarian colleague, nor a pharmacist from Vienna. It was only in Germany that project manager Andrei found what she was looking for. A pharmacist in the Bavarian town of Hof was able to get the medicine. However, Teodor’s mother had to pay the €750 euros for 20 capsules out of her own pocket, because health insurance does not cover medicines purchased abroad.

“We parents of children with cancer are too exhausted to protest against the conditions,” says Oprea. She wears a black jacket and grey tracksuit bottoms; the logo of a discount retailer can be seen on her yellow backpack. In hardly any other EU country do people have to pay as much for medicines out of their own pocket as in Romania. And in no other country does the state spend so little per capita on drugs.

Since the financial crisis in 2009, in particular, the Romanian government has been trying to save on medication costs. As is common practice, costs are based on the drug prices paid in other EU countries; so far it has always taken the lowest price from a selected group of 12 countries that include Lithuania, Hungary and Poland. “What sounds sensible at first, is exactly the problem: the drugs in Romania are too cheap,” says Razvan Pavel, who works in the Department of Medicines Regulation at the Ministry of Health. The classic cancer drugs that have been used for chemotherapy for years are now so cheap in Romania that it is simply no longer worthwhile for pharmaceutical companies to market them there. The result: the drugs never even make it onto the market, or if they do, at some point they disappear. Often, other companies buy the drugs in Romania and then sell them on to buyers in other EU countries such as Germany, at significantly higher prices. This is not illegal.

“We neither know how many people are suffering from which cancer, nor how many drugs we have in stock at what time in Romania”

It should be possible to block the export, at least in theory, when the drug in question is in short supply in the country. In practice, however, there is still no registry where the stocks of drugs in Romania are recorded, just as there is still no national cancer registry. “We neither know how many people are suffering from which cancer, nor how many drugs we have in stock at what time in Romania,” says Pavel.

The 32-year-old flips open his laptop, quickly opens a website that is for Ministry staff only, and scrolls through a table, column by column. Pavel, dressed in a dark jacket and crease-free shirt, with a well-groomed five-day beard, used to work for Magic, but is currently working day and night to develop a kind of alarm system that will indicate in yellow, orange or red to warn about an imminent shortage of a particular drug. Romania’s circa 10,000 pharmacies already have to report to the Ministry on which medicines they currently have in stock. Pavel’s new algorithm should help to integrate and analyse this information.

The Government has managed to somewhat improve the situation in recent months. Since July 2021, the Ministry of Health no longer has to base its costs on the cheapest drug price of the 12 EU countries. Instead, the average price from the three cheapest countries is used for a selection of particularly important drugs. The result? ‒ that the drugs are a little more expensive. “This makes the Romanian market more attractive for pharmaceutical companies,” says Vlad Voiculescu, who has been Minister of Health twice, most recently until April 2021.

In contrast to many health ministers before him, Voiculescu had publicly addressed the shortage of cancer drugs and suggested the new regulation. But he was unable to change very much, he explains, as he was out of the job too quickly. “All in all, I had only ten months in office,” says the 38-year-old. This is not unusual in Romania, where more than 30 health ministers have been appointed and dismissed over the past 25 years.

One woman had received her chemotherapy only because she was the youngest on the ward. Two others had gone away empty-handed

Voiculescu was also the person who started transporting cancer drugs to Romania all those years ago, which explains his interest when he became Health Minister. In 2008, long before he became a politician, he worked as a bank clerk in Vienna. A former classmate who had become a doctor, asked him to bring essential medicines for six children with cancer. “Until then, I had no idea that the drugs were unavailable,” recalls Voiculescu. A little later he met a woman who had received her chemotherapy only because she was the youngest of three cancer patients on the ward. The other two had gone away empty-handed.

Voiculescu still supports the organisation with ideas and contacts; he sits at the table while Adriana Andrei talks about how the network has grown over the years, from five to 35 employees today. Just as Voiculescu once did, three days later Andrei will also be collecting medicines, in a small town in neighbouring Bulgaria that must not be named here. In a sparsely lit side street, a pharmacist will hand her ten packs of methotrexate in a plain paper bag, a medicine used in many chemotherapies. In a grey cool box he will also provide ten bottles of an infusion that is essential, particularly for treating patients with bladder cancer. The pharmacist does not want to be seen handing them over, fearing inspection by the authorities, even though the sale of the drugs is not illegal.

In the meantime, other organisations are imitating the network, such as the Medicine Box ‒ Cutia cu Medicamente ‒ another Bucharest-based initiative. In contrast to Magic, here the patients never have to pay for the medication themselves, as they are financed by donations. Some pharmacists, such as Corina Salagean in the city of Brașov, even produce certain treatments themselves. At the back, in the windowless laboratory in the grey concrete building, an assistant is pouring a powder into one hundred brown-and-white capsules ‒ an antibiotic for cancer patients with weakened immune systems. On a white shelf, an ointment is ready in a plain plastic container for a patient with melanoma. “Ten years ago we could still order the ointment, but today it is no longer available in Romania,” says Salagean. So the pharmacist often steps in.

Teodor’s mother also wants to help. She is even willing to share her boy’s 14 remaining capsules with others. Magic has already received another request for exactly this cancer drug, reports Adriana Andrei. Another patient has run out of his supply, and urgently needs a capsule.

This article was written with a Cancer Journalist Grant from the European School of Oncology. A similar version was published on 21 October 2021, in the German weekly news magazine, Der Spiegel. It is the first of two linked articles exploring issues of pricing and access to cancer drugs across the EU. It is republished here with permission. © Astrid Viciano

Photo: Petrut Calinescu ©