Ian Magrath, lymphoma specialist and champion of cancer care in the developing world, has died in Brussels, aged 78. An exceptional cancer researcher, physician and teacher, he will be remembered for his pioneering role putting cancer care on the global health agenda.

Magrath was among the earliest voices to challenge perceptions that cancer is a disease of high-income countries. More importantly, he showed an often sceptical medical and global health community that, with appropriate research and evidence-based strategies, cancer can be treatable in even the poorest settings. His efforts undoubtedly helped pave the way for the increasing attention the global health agencies, and governments in the global South, are finally beginning to pay to building capacity to tackle cancer.

Magrath’s international role began in earnest in 1999 when he was appointed director and chief scientific and medical officer of the International Network for Cancer Treatment and Research (INCTR), which had been established the previous year by the Brussels-based Institut Pasteur and the UICC (then known as the International Union Against Cancer). The move entailed leaving the financial security and status of a senior post at the heart of the US cancer establishment to set up an initiative that offered neither of those things. But Magrath had long been looking for an opportunity to dedicate himself full time to addressing the cancer needs of developing countries, and he took it with both hands. He led the organisation for two decades until ill health obliged him to step back.

Magrath established the INCTR’s distinctive philosophy, based on working with physicians and pathologists within their own settings to build their capacity to do the research and clinical studies needed to understand the nature of the cancer challenges in their community and adapt existing knowledge and guidelines to most effectively address those challenges using the available resources.

The approach was in stark contrast to many well-meaning initiatives taking place at the same time that focused heavily on parachuting in technologies and treatment approaches from high-income settings, which were often poorly aligned to either the needs or the capacities of the recipient countries.

Magrath described his approach in an interview with Cancer World in 2010. “You need to understand local resource limitations and do the research that’s regionally appropriate. You have to be prepared to train and educate the professional staff – select a disease or discipline, and one or more centres, and try to develop those into centres of excellence or reference centres, with whom we can work on a long-term basis, so that you develop a standardised, evidence-based approach to treatment, agreed with colleagues.”

Over the past twenty years that approach has begun to gain prominence within the global cancer community, but Magrath and the INCTR were well ahead of the curve. The founding concept of building a network, which recognised that knowledge doesn’t just flow from North to South, was an essential part of the philosophy, as was the recognition that Western-led cancer research efforts could learn a lot from paying more attention to cancer in the rest of the world: included among INCTR’s list of objectives is, “To take advantage of unique opportunities for cancer research in developing countries.”

Driven by humanity and a belief in science

It was this scientific curiosity as much as humanitarian interest that lay behind Magrath’s first encounters with cancer outside a Western setting. Having completed his medical degree at the University of London in 1967, he continued his training as a senior house officer at London’s Charing Cross hospital, where he worked under Kenneth Bagshawe, a medical oncologist best known for being the first person to cure advanced cancer – a choriocarcinoma – with chemotherapy.

The experience triggered an early interest in medical oncology, and specifically lymphomas, which were also highly responsive to chemotherapy. Magrath was intrigued in particular by Burkitt lymphoma, which had been identified by Dennis Burkitt around a decade earlier, through some astonishing epidemiological detective work in equatorial Africa. The disease had recently been found to be caused by the previously unknown Epstein-Barr virus. Yet, while this virus appeared to be hugely prevalent in populations across the world, Burkitt lymphoma was confined to a very specific region. Understanding what lay behind this inconsistency would reveal important information about the cancer reasoned Magrath.

That is what prompted him to set out, in 1971, to take up a post at the Lymphoma Treatment Centre, in Kampala, Uganda, which was run jointly by the US National Cancer Institute and Makerere University. What he learnt during the three years he spent there would shape his future career. He saw children coming in with faces badly disfigured by swellings from the lymphoma being cured, sometimes with only one or two doses of chemotherapy – a living example of both the suffering that cancer causes in low-income settings and its treatability. He also saw that it was not just lymphomas where the pattern of cancer differed from the UK. Hepatocellular cancers and Kaposi’s sarcoma (this was before the AIDS epidemic) also seemed unexpectedly common. Magrath saw those disparities as important opportunities to learn more about those diseases, their pathology and risk factors.

The departure of the US NCI contingent triggered by a deteriorating security situation as Idi Amin consolidated his hold on power gifted Magrath access to some well-equipped laboratories where he was able to pursue some of the research. But when, in 1974, the NCI offered him a two-year contract to become a senior investigator at their new paediatric cancer branch at their headquarters in Bethesda, Magrath accepted and moved to the US.

The two years turned to 26, with Magrath being appointed head of the paediatric oncology section and head of the lymphoma biology section along the way. Here he carried out a combination of teaching, basic research into malignant lymphomas and the Epstein-Barr virus and some clinical research, publishing more than 170 scientific papers.

A global cancer pioneer

But he retained his strong global orientation. In 1976, still relatively junior in the organisation, he responded to an appeal from oncologists in Chennai (then known internationally as Madras) for help improving their desperately poor survival rates for paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. He examined specimens they sent him and got details of the treatments they were using, and later visited the centre, convincing them to change their focus on setting up a bone marrow transplant unit, but working with them, instead, to ensure the standard therapy was being applied appropriately, and also adapting it to the needs of their particular patient population.

That protocol, which soon spread to centres across India and beyond, pushed up four-year event-free survival rates from less than 20% to between 45% and 60%, and has been further developed over the years with survival rates up to 70% – not far from those achieved in Western countries.

After leaving the NCI to head up the INCTR, Magrath would work with colleagues in Tanzania, Nigeria, and Kenya, to develop a three-drug protocol for Burkitt lymphoma, with a salvage regimen for patients with persistent or recurrent disease, that would similarly help push up survival rates from 10–20% to more than 60% for patients in these and neighbouring countries.

These are impressive legacies by any standards. But it is the less visible legacy of Magrath’s work – building local capacity and confidence in doing scientific research and evidence-based medicine in places with only the most basic resources and infrastructures – that may well be his most lasting contribution to efforts to tackle global cancer. With the World Health Organization now urging governments to prioritise efforts to tackle cancer in their public health and healthcare programmes, local experience about how to understand what needs to be done, and develop ways to do it within the realities of local resources and infrastructures, are proving essential. It’s a fair bet that the local expertise that Magrath and the INCTR set out to build 25 years ago will now be actively engaged in helping make the most of these new opportunities.

The WHO’s own cancer agency IARC has posted a fond tribute to Magrath, recognising the personal commitment and dedication behind the work he did. “Dr Magrath was an idealist. A gentle man and a gentleman, he was determined to make a difference in his chosen calling: building capacity for cancer treatment in countries where resources were either poorly provided or non-existent. He was in many ways a visionary. In the first decade of this century – when there was little or no interest in the concept of ‘global cancer’ – through INCTR he built up a worldwide network of clinical and scientific experts. Compassionate and generous to his colleagues, he placed a high value on collaboration and service to others.”

Franco Cavalli, founding and current president of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma and Chair of the World Oncology Forum, is one of only a handful oncologists to match Magrath’s long track-record flagging up the urgent need to address cancer in the global South. He remembers Magrath as “unique, in the sense that he was the only one able to invent and successfully apply both highly efficacious treatments for lymphomas in Western settings as well as in developing countries, with the latter often being both simple and manageable.”

Striving to save and help children with Burkitt lymphoma was his “unrelenting passion,” says Cavalli. “I was once with him in Tanzania and was moved to see how totally absorbed he was by this vision.”

Not surprisingly, he adds, when the proposal for convening the 2012 World Oncology Forum was first mooted, to spell out the potential economic and human consequences of the rising tide of cancer in developing countries, as well as evidence-based strategies to avoid them, Magrath was among the first to give the idea his enthusiastic backing.

Cavalli also highlights how important the success stories of curing childhood leukaemias and lymphomas in resource poor countries remain as examples to point to in ongoing efforts to convince governments and global health organisations of both the feasibility and the huge benefits of tackling global cancer.

In 2018, the WHO launched its Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer. Among his many other achievements, Magrath deserves recognition for his pioneering role in making that happen.

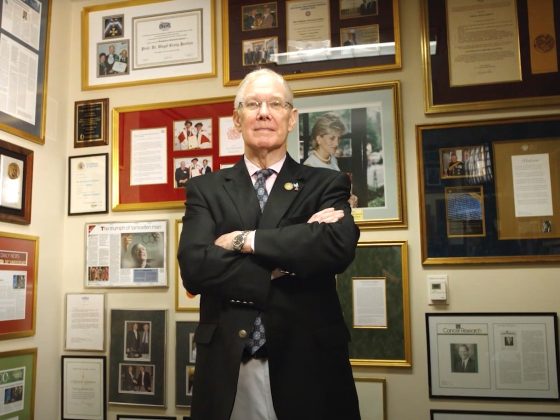

Image, courtesy of INCTR, shows the Burkitt lymphoma ward in St Mary’s Hospital, Lacor, Uganda, one of the centres involved in the INCTR Burkitt lymphoma programme. Image of Ian Magrath is taken from a 2012 video interview with e-cancer on Cancer In Developing Countries.