Responsibility for scientific evaluation, supervision and safety monitoring of medicines was done at the national level until 1995, when EU member states agreed to coordinate that work within the European Medicines Agency (EMA). A quarter of a century on, and the landscape of drug development has changed dramatically, with the emergence of translational research, big data and precision medicine, while patients have found their voice with the emergence of patient advocacy groups at national and European levels.

To mark its anniversary, the EMA invited leading voices from the cancer community with a stake in the development and approval of cancer drugs to share their perspectives in an online meeting entitled ‘New approaches in patient-focused cancer drug development’.

Opening the meeting, EMA director Guido Rasi presented the agency’s own perspective, focusing on issues of trust and relevance. He highlighted its efforts to be more transparent in publishing clinical data, and to build on the involvement of patients. He talked about a recent initiative to work with the health technology assessment field to ensure the data required from drug developers sheds light on the extent of clinical benefit. And he emphasised the need to gather data after drug approvals to learn about the performance of agents in real-world settings and how to use new treatments to best effect. These themes permeated the discussions that followed.

Clinically meaningful medicines

Solange Peters, president of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), addressed the challenges of affordability and access, which have increased over the past 25 years as cancer has become a leading cause of death globally, and costs of treatments have risen, not least for cancer drugs, which now comprise 10−15% of drug approvals.

“The biggest challenge for us in oncology is defining what is a clinically meaningful medicine,” said Peters. She highlighted the challenge of rare cancers and emphasised the importance of implementing innovative trial methodologies and focusing on precision medicine, also echoing Rasi’s point about the need to consider real-world evidence.

Peters pointed to the ESMO Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO−MCBS) as a key innovation that is now widely used to improve decision-making regarding the value of anti-cancer therapies, including by the World Health Organization to help compile its essential medicines list. The ESMO scale is also demonstrating that the benefit derived by patients does not correlate with the cost of drugs – paying more does not necessarily provide a better drug, she added. Currently applicable only to solid tumours, Peters said the scale could be expanded to cover haematological agents as well.

“The ESMO scale is demonstrating that the benefit derived by patients does not correlate with the cost of drugs”

Addressing access to anti-cancer therapies, she stressed the importance of the link between regulatory authorities and health technology assessment, and pointed to efforts outlined in EMA’s strategy up to 2025 to strengthen such links. She also mentioned ESMO’s work on identifying drug shortages, saying it is planning to conduct a new survey of drug availability, having last published one in 2017, and adding that access to biomarker testing also remains a problem across Europe.

Stella Kyriakides, European commissioner for health and food safety, talked about the many EU initiatives that could help promote development and access to effective, affordable anti-cancer therapies. These include Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan, which will address prevention and early diagnosis to treatment and quality, with patients and survivors at its centre; the EU’s new pharmaceutical strategy, designed to secure the supply of affordable medicines to meet citizens’ needs while protecting the role of the European pharmaceutical industry; and the European Health Data Space, which could boost research through pooling information such as electronic patient records. An overarching programme is EU4Health, which kicks off in 2021 and will include actions to strengthen health systems and support disease prevention and health promotion. Kyriakides also talked about disruption to cancer care during the Covid-19 pandemic, and took the opportunity to thank the EMA for its work on monitoring drug shortages and supporting the continuation of clinical trials during this difficult period.

Patient-centred research

Denis Lacombe, director-general of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), emphasised the importance of academic research, partnerships with industry and the ways in which treatment optimisation can be carried out in the real world following regulatory approval ‒ a topic that the EORTC has been majoring on recently (Beishon M. Cancer World 2020). The priority is to reduce uncertainty amid much complexity in drug, diagnostics and device development in favour of addressing the issues that patients and their doctors identify as important. It may mean unlearning traditional development processes and working back from patient and societal needs, said Lacombe, who added that new datasets and methodologies will need to be harnessed, and more attention will need to be paid to academic pragmatic research.

Martin Dreyling, a lymphoma and leukaemia specialist at the LMU clinic in Munich, noted that while the administrative burden of clinical trial regulation has increased greatly, patient safety has not increased, and may even be decreasing, because ‘safety signals’ are getting harder to detect. He added that the way informed consent is put to patients is too hard to understand (see also Hutchinson L. Cancer World, 2018). Dreyling drew attention to a call led by the European Hematology Association to reduce the bureaucracy of trials, supported by many other medical societies.

Patient input into regulatory and HTA processes

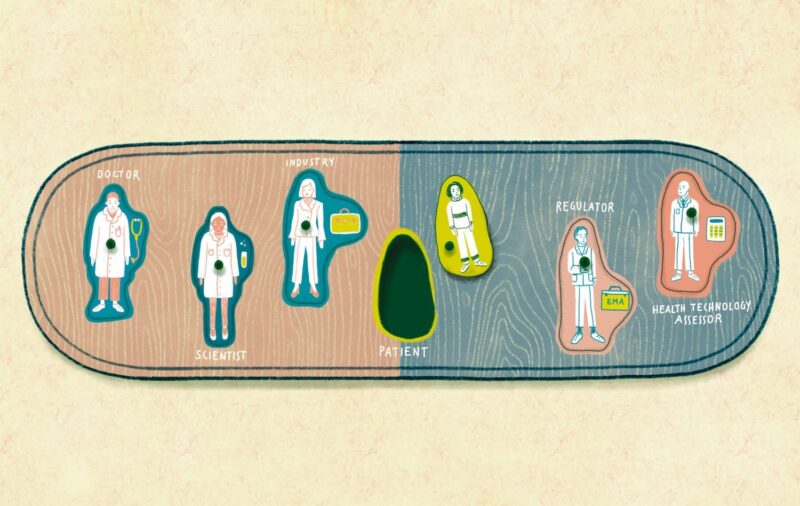

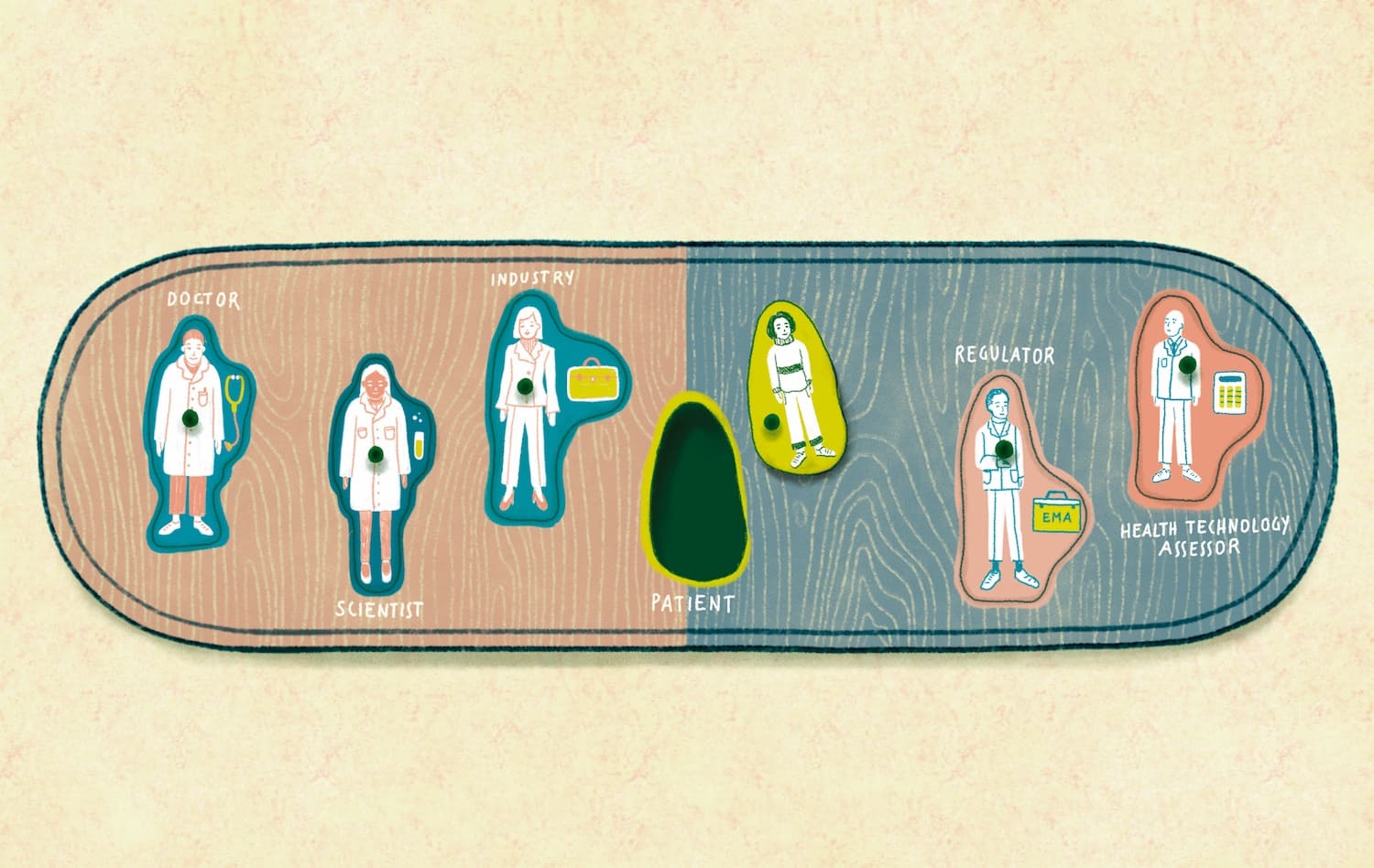

Jan Geissler, one of the founding members of the European Cancer Patient Coalition (ECPC), and currently head of Patvocates − a patient advocacy think tank − traced the journey that patient advocacy has travelled and the choices that patients still face among often unattractive options that may be determined by other stakeholders in cancer care.

He looked at the different priorities driving some of those stakeholders. Regulators are concerned with efficacy and safety; health providers focus on healthcare sustainability, which may favour society as a whole over cancer patients; researchers may have conflicts of interest; and physicians may be focused on clinical outcomes that do not include patient preferences. “Whose preferences should decision makers take into account when they take regulatory decisions?” he asked.

Geissler referred to a chart from the early days of cancer patient advocacy that showed a mismatch between what doctors and patients reported as major adverse effects of drugs. He also pointed to differences in preferences within the patient population. In comparing two drugs, one of which offers a large medium-term survival versus one that offers a much longer survival but to fewer patents, how can approval choices be resolved in line with patient preferences, given that any two patients with equivalent disease may have different preferences, he asked.

Geissler pointed to work at the EMA on analysing preferences among myeloma and melanoma patients more deeply than information usually gathered in surveys. Methodologies are needed to examine trade-offs between factors such as toxicity, benefits, and time, and patients must be included in the process, he said, adding that patient advocacy can provide the enabling framework.

“Methodologies are needed to examine trade-offs between factors such as toxicity, benefits and time”

Geissler showed a roadmap on how patients can be involved at different stages in the drug development lifecycle, as pioneered in the HIV/AIDS community, and where risk‒benefit can be examined. He showed how the EMA has responded to patient involvement, but said the impact of patient involvement in regulatory processes still needs to be evaluated, and major challenges remain regarding the capacity of patient organisations to participate, such as if someone has to take time off work to attend committees.

In a complementary presentation, Jorien Veldwijk of the Erasmus Choice Modelling Centre, in the Netherlands, pointed out that just including one or two patients on regulatory panels may not be sufficient to reflect the spectrum of a patient opinion in what could be a large population. She talked about the challenge of gauging the preferences of a population of patients, especially for drugs and medical devices not yet on the market, where a conventional survey would not suffice.

Veldwijk described methods that can model preferences, such as for a new drug over the standard of care, in terms of risk and other factors, and that take into account heterogeneous demographics. There are guidelines for some such methods but not yet all, she added, and there are several initiatives underway in health preference research (see for example the PREFER site). One example of a cancer-related project is in lung cancer, weighing up chemotherapy and immunotherapy options.

Kathi Apostolidis, president (now past-president) of ECPC and a two-time breast cancer survivor, spoke about her own experience on the EMA’s Patients and Consumer Working Party. EMA involvement is more than just attending meetings, she said, but also includes providing input to documentation such as patient information leaflets. She noted that while there are opportunities to find patients with certain cancers to participate at the EMA, they need to be empowered to do so. Apostolidis joined the steering group of the European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance (ENCePP) as an EMA observer, where she helped to get patients mentioned in ENCePP’s code of conduct. The experience so far at the EMA would now benefit from being organised into various topics to help inform others participating in similar activities, she said.

Responding to the discussion, with particular reference to the issues raised on values, trade-offs and preferences for patients, the EMA’s senior medical officer, Hans-Georg Eichler, commented that people generally see the EMA as a body that assesses drugs and makes decisions on approval. There certainly is an assessment stage, he commented, but then there is a second step that is often not spoken about, which is appraisal, and is about values and preferences. Do benefits outweigh risks, and is the uncertainty acceptable? Eichler argued the assessment stage is best left in the hands of experts, but appraisal is where we should ask, whose values count? “I guess we can all agree it should ultimately be patient values,” he said.

“Appraisal is where we should ask, whose values count? I guess we can all agree it should ultimately be patient values”

He described the steps required to bring patient values to bear, saying it is important to be explicit about the assessment and appraisal steps, but noting that this is rarely done. He mentioned NICE – the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK ‒ as a body that makes an explicit distinction between the two steps, and said the EMA is looking to follow suit. The benefits of some drugs are so clear that a lengthy process is not necessary, but with many oncology drugs, patient views on benefit are important, said Eichler, and he referred to Jorien Veldwijk’s presentation on models for involvement. Developing a scientific way of integrating patient voices in the decision-making process could also be important, he said.

Special challenges

Rare cancers

The perspective of the rare cancers community was given by Paolo Casali, a sarcoma specialist at the Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori in Milan. He spoke about the need to bridge gaps between regulators and the patient−clinician community to help address unmet needs. Too many rare cancers are still treated with off-label drugs, he noted. The European Reference Networks (ERNs) initiative, which is to be expanded in the EU4Health programme, can play an important role, he said, as there are ERNs for rare adult solid cancers, haematological cancers, and paediatric cancers that can develop the evidence base to feed into regulatory decision making. Expanding these networks beyond major centres remains a challenge, however (see also Fessl S. Cancer World 2020).

Paediatric cancers

Gilles Vassal, a paediatric oncologist at Institut Gustave Roussy in Paris, talked about the challenges faced by the childhood cancers community. He said about 60% of patients participate in trials, which are mainly academic trials, with many using off-the-shelf drugs. Only 5% of paediatric patients are enrolled in industry trials. Clinical research is mainly under the umbrella of the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE), which helps to deliver best care as well as research in Europe.

The main obstacles, he said, are inequalities across Europe in accessing clinical trials, administrative burden, and insufficient collaboration at wider international levels. Opportunities include innovative trial designs, working with HTA agencies, and strengthening partnerships with industry and regulators.

Palliative care

Giovanni Navalesi, medical director at the Antea Foundation, a centre for palliative care and research in Rome, talked about the importance of individualised palliative care. He pointed out that harmful psychological and physical effects do not come only from cancer itself, but can also be caused by anticancer treatments and drugs used to alleviate other symptoms.

Navalesi highlighted gaps in the clinical data for palliative care, noting that less than 1% of clinical trials in cancer are dedicated to palliative care, and the quality of these studies is often not very good. He called for greater cooperation between the oncology and palliative care sectors, and said there needs to be wider understanding of the scope of palliative care, from its early introduction to end of life, and in home-based care as well as hospice care. “There needs to be more public funding of clinical studies in palliative care”, he concluded, noting an initiative to build an international network of palliative care registries for collecting real-world data that has 18 members so far (the International Registry of Palliative Care – for details email [email protected].).