The nature of the doctor–patient relationship has gone through various phases in history, based on the changing role of the physician in the community, as well as progress in medicine and increased choices of care, together with better-informed patients. Broadly speaking, the shift in the dynamic between doctor and patient has been from an active‒passive relationship towards guidance‒co-operation, and more recently mutual participation.

Within Europe, cultural changes over many decades have seen a significant shift towards mutual participation, with an emphasis on informed patients and shared decision making. And with the recent rapid rise in the therapeutic options available to treat cancer, the quality of the discussion between doctor and patient has become increasingly important in ensuring that the treatment strategies now available are used to best effect.

Yet while the nature of the relationship may have changed significantly throughout history, the quality of that relationship has always been central to quality care.

Doctor‒patient relations through the ages

A doctor figure has probably always existed in human communities. There are cave paintings representing healers that date as far back as fourteen thousand years ago. Before the secularisation of medicine brought in by the Hippocratic school in the 5th Century BCE, there were no clear-cut boundaries between medicine, magic and religion, and the doctor‒patient relationship would have been an extension of the priest‒supplicant, with an expected compliance from the patient, and less personal responsibility on the part of the doctor, who was after all acting out the will of a god.

In medical literature, encounters between doctors and patients were usually described by doctors, and are thus limited to their observation and treatment of the patient, and their own professional and moral code. We might be told the outcome of a therapy, but the patient’s opinion remains unknown. The most conspicuous exception to the rule comes from the 2nd Century CE. The Greek orator Publius Aelius Aristides suffered long bouts of poor health (real or psychosomatic) and sought relief in the worship of Asclepius, the god of medicine. He spent much of his time as a patient at the Asclepeion of Pergamum, where his god-induced dreams were interpreted into cures. Eventually, Aristides wrote the Sacred Tales, six books in which he records the revelations he received in dream by the healing god. At the beginning of Book 1, in an entry dated winter 170 CE, we read, “I decided to submit truly to the God, as to a doctor, and do in silence whatever he wishes,” ‒ a dramatic example of passivity.

Bedside manner

Before the relatively recent introduction of patient satisfaction questionnaires, and Aristides aside, to learn about the doctor‒patient relationship from the patient’s perspective we must turn to fiction. Fictional characters can, of course, be somewhat biased, as they are intended to trigger a reaction in the reader. Nevertheless, it is fascinating to see how certain behaviours and deportments have been present ‒ and contested ‒ throughout history.

One of the oldest human dilemmas for doctors is the delicate balance between expectations and reality ‒ how to protect the patient’s hope without lying

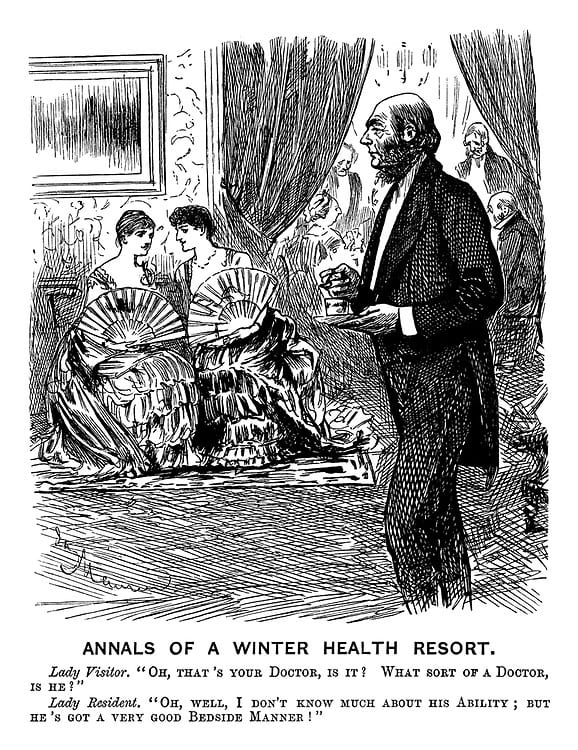

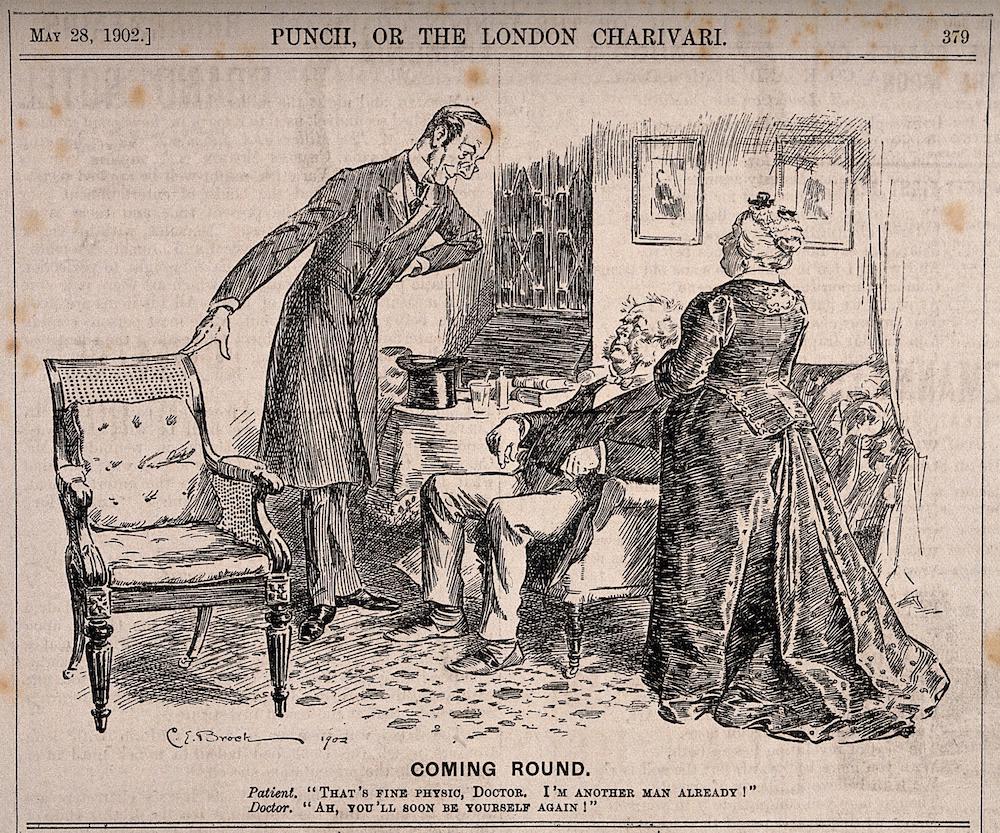

The first time the expression ‘bedside manner’ was recorded is in a famous cartoon published in the British magazine Punch in 1884: “Lady Visitor: ‘Oh that’s your doctor, is it? What sort of a doctor is he?’ Lady Resident: ‘I don’t know much about his ability, but he’s got a very good bedside manner’.” Rightly or wrongly, this was interpreted as meaning, “the manner that a physician assumes toward patients”. One of the oldest human dilemmas for doctors is the delicate balance between expectations and reality – that is, how to protect the patient’s hope without lying. This is no easy task, not least because patients seem very skilled at recognising when their doctor is not being straight with them. In one of Aesop’s fables (thus dating back at least to the 6th Century BCE), a sick man tells the doctor his dreadful symptoms, and every time the doctor comments, “That’s good”, “That’s fine”. Finally, a friend asks the patient how he is feeling, and the patient replies, “I am dying of good signs.” The moral of the fable is: “A death-bed flattery is the worst of treacheries.”

The first time the expression ‘bedside manner’ was recorded is in a famous cartoon published in the British magazine Punch in 1884: “Lady Visitor: ‘Oh that’s your doctor, is it? What sort of a doctor is he?’ Lady Resident: ‘I don’t know much about his ability, but he’s got a very good bedside manner’.” Rightly or wrongly, this was interpreted as meaning, “the manner that a physician assumes toward patients”. One of the oldest human dilemmas for doctors is the delicate balance between expectations and reality – that is, how to protect the patient’s hope without lying. This is no easy task, not least because patients seem very skilled at recognising when their doctor is not being straight with them. In one of Aesop’s fables (thus dating back at least to the 6th Century BCE), a sick man tells the doctor his dreadful symptoms, and every time the doctor comments, “That’s good”, “That’s fine”. Finally, a friend asks the patient how he is feeling, and the patient replies, “I am dying of good signs.” The moral of the fable is: “A death-bed flattery is the worst of treacheries.”

One of the best and most enlightening collections of doctor–patient passages in literature is provided by Solomon Posen in his book The Doctor in Literature (2005). Posen was an endocrinologist and expert in bone and mineral diseases in Australia. He also had a deep knowledge of literature. One of the main purposes of his book was “to identify and analyse a number of themes that constantly recur in the portrayal of medical doctors, especially themes that seem unaffected by time, place, or clinical training.” In his opinion, the basic relationship between patients and physicians remained essentially unchanged over two and a half millennia.

The experience of internist and rheumatologist Ed Rosenbaum, as described in his 1988 autobiography, A Taste of My Own Medicine: When the Doctor Becomes the Patient, would seem to bear this out. He practised as a doctor for fifty years before becoming a patient in the same hospital where he used to work. “It wasn’t until then that I learned that the physician and the patient are not on the same track,” he writes. “The view is entirely different when you are standing at the side of the bed from when you are lying in it.” The film The Doctor, which came out in 1991, was based on that autobiography. Both film and book show typical doctor–patient encounters that we can all relate to, and of which we see examples throughout literature. Why do doctors, like the one in Aesop’s fable, have to tell us what they think we want to hear? Why can’t they be more straight with us, so we know where we stand and can make informed decisions? And why do they use such patronising language, as in: “How are we today?”, “This won’t hurt”, “Just a little prick”? Of course, a good doctor is preferable to a charlatan with a good bedside manner, and ultimately the physician and the patient’s goal is the same: the best possible outcome for the patient.

From family doctor to guidelines and waiting rooms

Aside from basic remedies and surgical interventions, medicine that actually cures is a somewhat recent phenomenon in human history. The period from around the 15th to the 18th century saw a gentle upward curve of medical discoveries, which was followed by a steep rise in the 19th and 20th centuries, and then an astonishing exponential growth in the past few years, spurred by massive technological advances.

Until the past couple of decades, all patients were pretty much treated the same from the medical science perspective, with a few guidelines on adapting protocols according to co-morbidities, age, and allergies.

Most of that tailoring was done by the doctor, based on their general experience and personal acquaintance with the patient. “That big back of his has curved itself over sick beds until it has set in that shape. His face is of a walnut brown, and tells of long winter drives over bleak country roads, with the wind and the rain in his teeth.” This is how Arthur Conan Doyle describes Dr. James Winter, in the short story Behind the Times (1894). Those of us who are old enough should ‒ but often don’t ‒ remember doctors’ house calls. The patient, surrounded by family, in their own environment, waits for the doctor with a mixture of fear and expectation. And, come rain or shine, the doctor arrives, often out of breath, carrying a bag of tools, ready to dedicate their entire soul and expertise to that one patient. The rest of the world can wait outside the front door. The doctor’s bedside manner and judgement might be poor or passable, but the dedication felt real.

On their own turf, the doctor always seemed too busy with other patients, paperwork, interruptions, to care about that one patient

But the axis has now shifted decisively from house calls to waiting rooms in doctors’ practices. In the clinic, the naturally skewed relationship between doctor and patient became more pronounced. On their own turf, the doctor always seemed too busy with other patients, paperwork, interruptions by nurses and colleagues, to care about that one patient. But then things started to change.

Putting the patient back at the centre

While healthcare was becoming technologically and scientifically ever more advanced toward the end of the 20th century, it was also becoming increasingly impersonal, which negatively reflected upon the outcome for patients, especially those with a chronic illness. Businessman and philanthropist Harvey Picker and his journalist wife Jean, who had a terminal condition, understood this, and decided to do something to improve the situation. In 1986 the couple founded the Picker Institute, a not-for-profit organisation dedicated to researching how healthcare systems can improve the experience of patients. Harvey Picker is widely credited with coining the term ‘person-centred care’. The institute set out the seven principles of person-centred care that are still at the core of high-quality care delivery.

Many organisations have since been created worldwide to empower the patient, by providing them, their families and their carers with support, information and involvement, and patient-centred care now tops the agenda in the healthcare revolution.

Principles of patient-centred care

The seven principles of person-centred care, originally established by the Picker Institute, are:

- Fast access to reliable healthcare advice

- Effective treatment delivered by trusted professionals

- Continuity of care and smooth transitions

- Involvement and support for family and carers

- Clear information, communication, and support for self-care

- Involvement in decisions and respect for preferences

- Emotional support, empathy and respect

- Attention to physical and environmental needs

The cultural shift to more patient-centred care has been reflected in challenges to the dominant terminology, for instance with the word ‘patient’ ‒ which can be seen as denoting a passive role, where the doctor has all the agency ‒ being substituted by ‘client’, where the doctors is seen as providing a service to people when they get ill. Discussions within the medical community about appropriate terminology were stimulated by Julia Neuberger’s article: ‘Let’s do away with “patients”’ published in the BMJ in 1999, although no consensus has yet been reached.

Patient-centred care in precision oncology

With its high-tech and complex diagnostics and treatment, involvement of multiple specialists in hospital and community settings, and its heavy physical and psychological burden, cancer is a challenging ‒ but most rewarding ‒ disease area to implement patient-centred care.

The emergence of personalised, precision approaches to treating the disease is in a sense moving the science itself towards patient-centred medicine, in which the precise molecular biology of their disease and their own body become central to the clinical decision making. Genome sequencing, microbiomes, concepts like artificial intelligence and ‘big data’, projects like the Human Cell Atlas, all point in the direction of personalised medicine, and personalised medicine enables and requires patients to play a greater role.

This progress is making the decision-making process considerably more demanding for both doctor and patient

And yet the progress this has brought to extending lives and improving the quality of life for many people with cancer is making the decision-making process considerably more demanding for both doctor and patient.

Until recently the scenario for cancer was pretty much black and white: there were patients with limited disease, who were curable, and patients with disseminated disease, who were treatable but incurable. Breaking and receiving bad news about a terminal condition was obviously very painful, but, in a sense, clear-cut.

Today, by contrast, there is a sort of limbo between the two conditions, where a cure remains unlikely, but where a growing number of options, associated with side-effects of varying severity, have been shown with different degrees of certainty, in specific patient populations, to hold back the disease and add varying degrees of benefit in both survival and quality of life.

The challenge for doctors is to help patients in this limbo make sense of their own situation, and the options available, so they can reach an informed decision on how far they are willing to go in risking the short- and long-term side effects, disruptions to daily life, and sometimes also expense, involved in pursuing particular treatment options for what likelihood of gaining additional months or years ‒ or even being cured.

From an historical perspective, therefore, the ideal doctor for the era of personalised/precision oncology is one who combines the close personal relationship of the traditional family doctor, on the one hand, with the scientific precision of the most up to date high-tech diagnostics and analytics, on the other … and then a ‘bedside manner’ that facilitates the informed discussion that is so key to working out the right treatment for the right patients at the right time.

With the contribution of Francesca Albini

Featured image credit: The doctor’s surprise. Oil painting after J.G. Vibert. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark