“If you want to be an oncologist you have to go through some struggles. First become a medical doctor and then enter a residents’ training in internal medicine and then medical oncology. If you want to do more, you have to organise your own training.”

“When you start, for every young doctor it is not easy. You get lots of duties, lots of paperwork, night shifts, and then at some point you realise that your dedicated oncological education is not really happening.”

“It is very, very simple having a structure, an institute, a university, who tells you: this is your curriculum, you have to do this, you have to have this exam and then you perform everything that is being told you. It is very difficult to go around Europe and look for [the training] you need.”

All medics are good at passing exams. The harder part is finding pathways to develop the knowledge and experience you need to take you where you want to be. The opening quotes come from three oncologists from Turkey, Bulgaria and Albania, who spoke to Cancer World in 2019 about their own journey towards becoming the best cancer doctors they can be in their chosen areas of clinical oncology, medical oncology and translational research.

Their CVs testify to the use they all made of a wide range of opportunities offered by professional oncology societies, universities across Europe and the USA, and even commercial bodies. What they had in common was making good use of the many opportunities offered by the European School of Oncology (ESO). These included attending ESO’s week-long ‘signature’ Masterclass in Clinical Oncology, where they received a grounding in providing individualised treatment and care, with a focus on the ‘five big killers’; spending several months working with multidisciplinary teams in leading European cancer centres as part of the Clinical Training Centre Fellowships scheme; and getting recognised specialist qualifications through the Certificates of Competence courses that are run by ESO in collaboration with the Universities of Zurich and Ulm, in lymphoma, breast cancer and lung cancer.

But their stories also testify to the difficulties young oncologists can face in negotiating a successful career, particularly if you are not lucky enough to train and work in a setting where seeking professional development is encouraged, and you lack a mentor to help point you in the right direction.

This July, the European School of Oncology opened the doors of its new ‘college’, ESCO, to enrolment by young oncologists looking for support and guidance in their efforts to navigate their way to becoming the best that they can be. The college is headed up by ESO’s deputy scientific director, Alex Eniu, a breast cancer specialist who trained and practised for most of his career at one of Romania’s top oncology centres, in Cluj. He brings to the job many years of experience leading efforts to improve oncology training and education in central and eastern Europe and in developing countries. Dean of the college is Nicholas Pavlidis, who founded and led the first, and highly-rated, medical oncology faculty (teaching and research) and a department of medical oncology (treatment and care) in Ioannina in north west Greece. He brings to the job a unique experience ‒ as student, teacher and organiser ‒ of the ESO’s almost 40-year history educating young oncologists in Europe and beyond. Pavlidis was one of the select few participants who attended ESO’s first ever oncology course, in Castello di Pomeria, northern Italy, in 1982, and then went on to develop and lead key areas of the School’s work including ESO’s Oncology for Medical Students courses and their regional work in the Arab world.

Why a college?

What alumni will encounter as they enrol in the college will look quite similar to the established ESO courses, fellowships and certificates. The added value to participants, says Eniu, is that these opportunities, plus some new additions, are now part of a formal educational pathway.

“Many educational programmes, particularly in eastern Europe, are not very structured, they don’t always follow the curriculum,” he says. “People start doing their residency, they will do some internal medicine, they will then start rotating in different wards in oncology. But they don’t have access to a structured educational path that will tell them: OK first you need to learn about the basic principles of chemotherapy, of surgery, of radiotherapy. Then you can go on and learn about different aspects of different tumour types. Then you are able to start understanding what you can do. In medical oncology, what weapons do you have? How does this link to what colleagues in radiotherapy and surgery can do?”

The idea of developing a college, says Eniu, came out of a realisation that “people are a bit lost… They don’t know how to complete their training. They don’t know what needs to be done next. They don’t have mentors, which I did, and they encouraged me [saying]: ‘It is good for you to go abroad for six months. This will change your perspective. You should now start writing an article. It is good for you to enrol into educational activities of your own…’”

The college is trying to do that, says Eniu, “To provide this educational pathway for students who want to enrol. It is a way of putting together everything that ESO does, but in a way that is more structured.”

“The idea of developing a college came out of a realisation that people are a bit lost… They don’t know how to complete their training”

The pathway

The ESO college presents itself as offering “aspiring medical, radiation and surgical oncologists a structured educational pathway that spans their career from medical student through to taking on leadership responsibilities”.

What this means in practice, says Eniu, is that applicants who have been selected by merit to attend, for instance, an ESO Masterclass, are invited to enrol in the college, where they can work their way up from student, to fellow, to graduate. Progress through the college is achieved by doing all the things that a good mentor would encourage a young oncologist to do: accumulating education and experience at home and abroad, building up a research and publishing track-record, learning to think critically and to lead.

It will start, he says, with a new event that he believes has been a missing link for some students who lack the basics needed to really benefit from the Masterclass ‒ a short course on the Basic Principles of Oncology. “Then perhaps you do one Masterclass, then if you have an interest you do one or two refreshers in a specific area. Then you realise that you need to do a fellowship to go abroad somewhere for three or six months to broaden your knowledge. And then you are probably ready to enrol in a certificate of competence. The college enables you to navigate your way through this career development. You are stimulated to go on the right track. You are given credits and taught which is your next step, with the goal of becoming someone who ‒ from the ESO perspective ‒ has acquired most of their capabilities and can be considered as a ‘completed oncologist’.”

Ultimately, he says, the intention is to offer, as a final step before graduation, a course in oncology leadership aimed at equipping participants to play a role in raising the quality of care in their own areas of work.

“The college enables you to navigate your way through this career development. You are stimulated to go on the right track”

Florian Lordick, a professor of oncology at Leipzig University in Germany who has been a scientific adviser and key faculty member of the ESO-ESMO Masterclasses for many years, agrees that a structured pathway to help those young oncologists as they progress their careers makes sense, and says the opportunities offered are well targeted “at the points people can benefit from support and contact with international faculty”. Like Eniu, though, he recognises that the unmet need is higher in some countries than others. “I come from a country where we have a lot of opportunities at a national level. We have an intensive training. We have some of these features already within our nation, but it is absolutely clear that this is not the same across Europe. There is certainly still a gradient between western and central/eastern Europe, particularly concerning international activities.”

Lordick adds, however, that the Masterclasses in particular, have always been an exercise in setting people on the road towards fulfilling their potential, rather than simply teaching them about oncology. It’s not so much about “stage by stage, how do you treat cancer,” says Lordick, who says he is always impressed by how much many of the participants already know. It is more about learning how to apply that knowledge to do the best for each patient ‒ “how to be a good oncologist”.

A central component of every Masterclass, he explains, is the chance to watch teams of “world-renowned experts” ‒ medical oncologists, pathologists, radiotherapists, surgeons ‒ discuss real cases. “The students can then ask questions and challenge the experts. Why did you decide to do it that way? Why do you recommend this? In my country you would do this differently. So there is this possibility to explore why the expert makes this recommendation.”

Crucially, he adds, the participants get to try out being ‘on the top table’. “Students learn how to present a case at an international level, and they each do their own presentation, which they then discuss among themselves… It is an exercise in training people for a future public position. They experience: how can I present myself? How can I present my knowledge? How can I defend my standpoint towards others?”

“It is an exercise in training people for a future public position. How can I present my knowledge? How can I defend my standpoint towards others?”

Results of a questionnaire recently sent to all participants who attended a Masterclass in Clinical Oncology between 2009 and 2016 showed that many are doing very well, testifying both to the quality of participants attending the Masterclasses and the value of attending. Six out of ten of them went on to train at university hospitals or cancer institutes, with one-third currently employed in academic centres. Four out of five had performed translational or clinical research, and a similar number had published in pertinent international journals.

Become best you can be

Pavlidis, founding Dean of the ESO College, points to ESO’s wider track record developing new generations of oncology leaders across Europe and beyond, many of whom have played their part in leading developments during a period that has seen rapid change ‒ in the science and technology, in levels of specialisation, in the culture of patient care.

Counted among his fellow students attending that first ever ESO course in 1982, for instance, were Gilberto Schwartsmann, who went on to lead New Drug Development Office at EORTC (the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer), Jaap Verweij, who went on to lead the medical oncology translational pharmacology unit at the Erasmus University Medical Centre in Rotterdam, and Robert Coleman who went on to lead global efforts to learn about and manage bone metastases from breast cancer.

Many of that first group of ESO students returned to contribute as faculty to ESO events, setting a pattern that continues to this day. With the new college now up and running, Pavlidis hopes that the opportunity to follow their footsteps, from student doctor to oncology leader, will now be more accessible to every enthusiastic and dedicated young oncologist, even those who lack the support, advice and encouragement that a good medical institution and a great mentor can and should offer.

ESO‒ESMO Masterclass in Clinical Oncology 2002‒2018

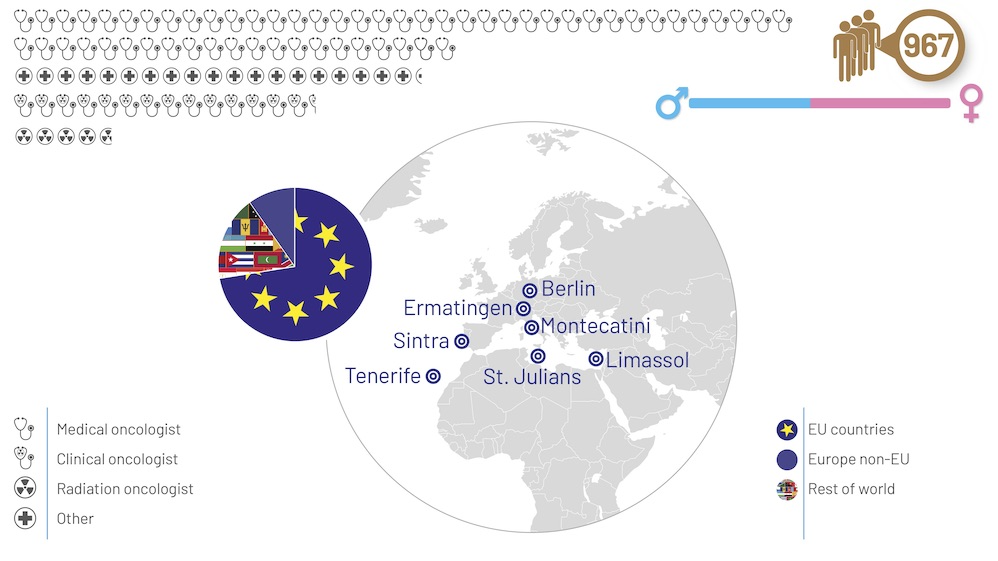

The ESO‒ESMO ‘signature’ Masterclass in Clinical Oncology has been held in a variety of European cities. The event is aimed primarily at medical, clinical and radiation oncologists, with less frequent involvement of other disciplines, such as surgeons and non-clinical specialties. The majority of participants come from EU Member States, with just over one-quarter coming from European non-Member States and from outside of Europe. The Masterclass offers students a full-immersion grounding in the medical principles of managing the ‘five big killers’. To develop their understanding of how to apply those principles to individual patients, participants have the chance to watch ‒ and question ‒ as real cases are discussed by multiprofessional teams of international experts. They also get practice in presenting their own cases for critical discussion by their fellow participants in faculty-moderated sessions (Pavlidis N et al, Eur J Cancer 2010).

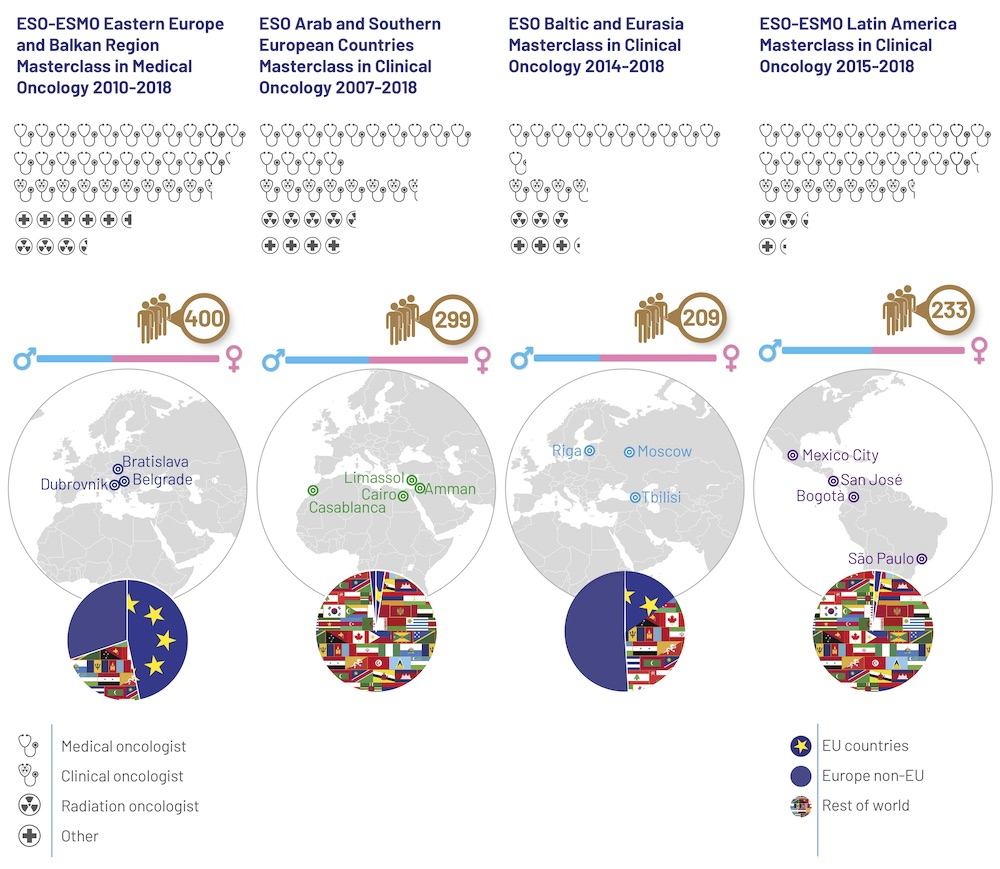

Regional Masterclasses

Regional Masterclasses were launched in recognition of differences across the globe in priority cancers and in health systems, resources and cultural traditions. The faculty is still made up of top international experts, but training is tailored to the local situation.

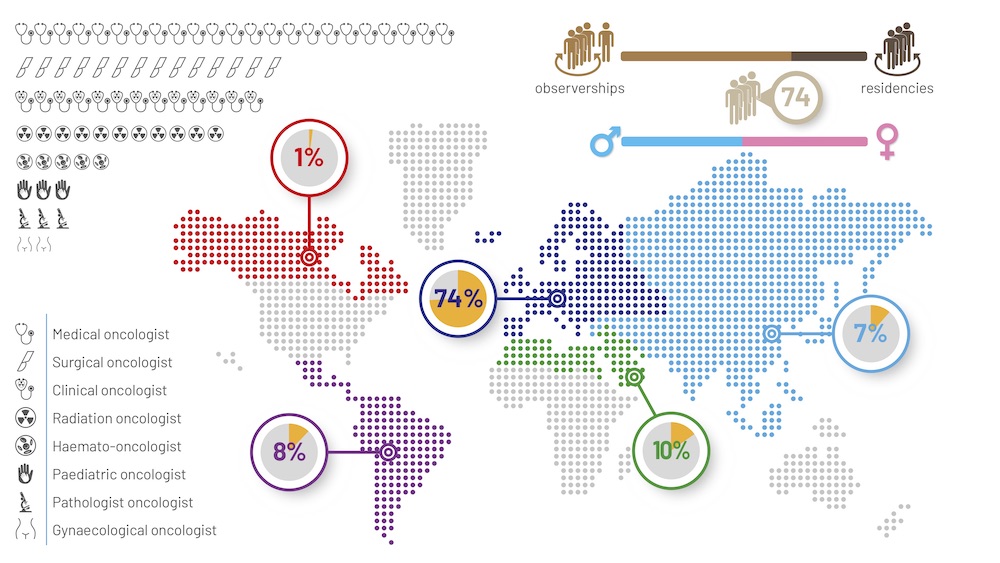

Clinical Training Centres fellowships 2013‒2019

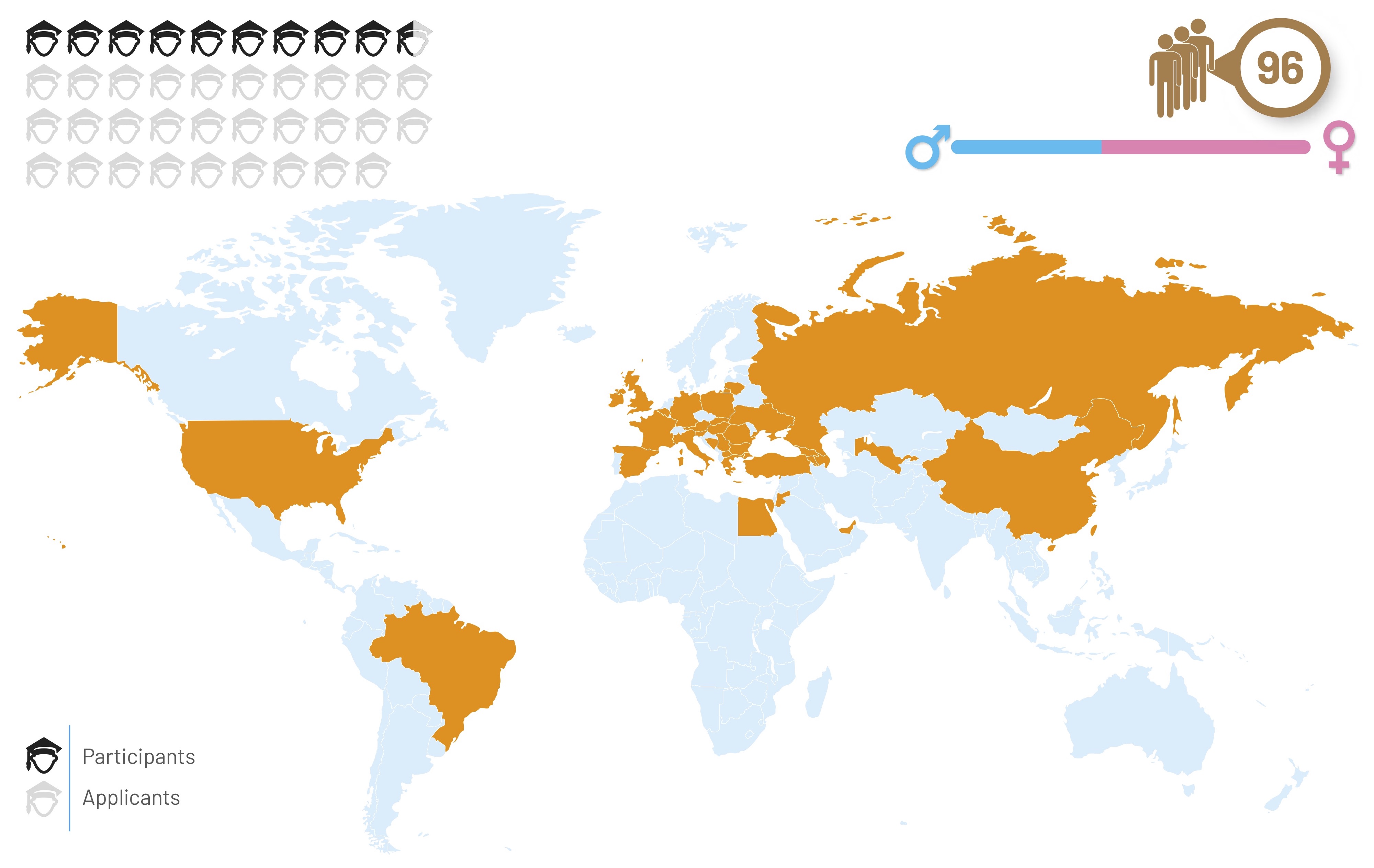

Clinical training fellowships offer young oncologists the chance to experience how patient care is managed at international centres of excellence. The fellowship is open to applicants working anywhere in the world, in all cancer care disciplines. Successful candidates get to spend three or six months either as observers or residents at one of the 15 collaborating centres. In the first six years the scheme has operated, three out of four fellowships went to young oncologists in Europe, from many different disciplines.

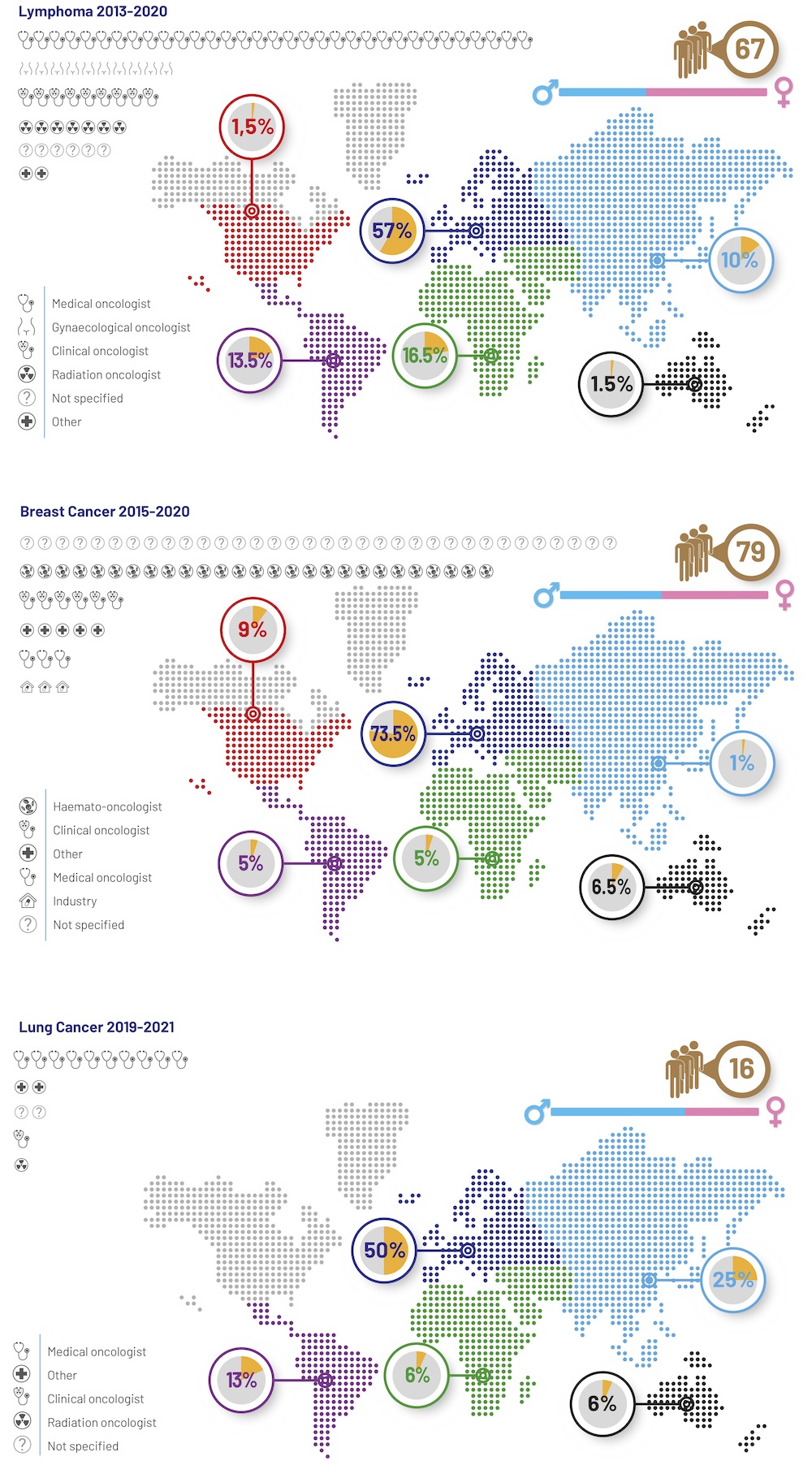

Certificates of Competence

Certificates of competence give oncologists the chance to study in-depth, and get a recognised qualification, as specialists in certain types of cancer. Courses are currently available for breast and lung cancer and lymphoma. They are run by ESO in collaboration with the University of Ulm, Germany (breast cancer, lymphoma), and the University of Zurich, Switzerland (lung cancer), and involve some face-to-face teaching as well as self-paced distance learning, for a total of 300‒400 hours of study. Students enrol from all over the world, with Europe accounting for at least 50%.

Multidisciplinary Course in Oncology for Medical Students

Summer courses designed to give medical students an idea of what it’s like to work in oncology have been run by the European School of Oncology since 2004. The Medical Students Courses in Oncology, started by ESO and later run in collaboration with the European Society for Medical Oncology, took place in Ioannina, Greece, between 2004 and 2011. Since then they have run annually in Valencia, Spain (Pavlidis N et al, Cancer Treat Rev 2007; Pavlidis N et al, Surg Oncol 2012). Due to the high demand, every year since 2017 an additional course has been run in Naples, Italy. Since 2016, ESO has also run annual courses for medical students in collaboration with the European societies for surgical oncology (ESSO) and radiation oncology (ESTRO), which rotate between the Universities of Antwerp (Belgium), Poznan (Poland) and Turin (Italy). The map below shows the data for the ESO-ESSO-ESTRO courses held between 2016 and 2019. These have proved very popular with medical students in many parts of the world, with around four students applying for every available place.