20th January 1933 ‒ 28th July 2021

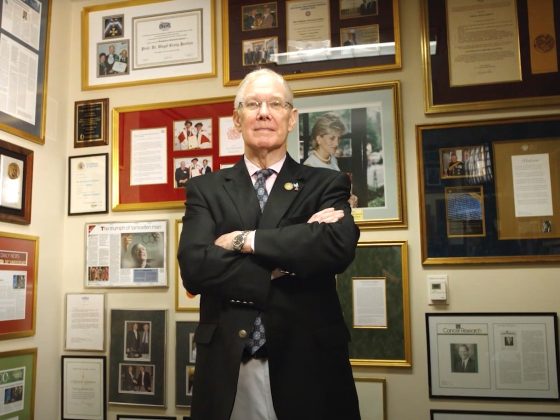

When Louis Denis described himself as a “free thinker”, as he often did, the statement went beyond a vague assertion of independence from dogma and lazy thinking. It was an agenda for action in medicine. Impressive lists of academic positions, clinical and administrative seniority and research contribution – bald at the best of times when it comes to summing up complex lives – singularly fail to do justice to one of urology and oncology’s greatest characters.

“As far as I can remember, I’ve always wanted to help people and fight against social injustice,” he said in 2004. “For me, medicine was the natural answer… I abhor power, arrogance and elitism.”

His disdain for political manoeuvring and professional apathy, along with his strong self-belief, inevitably brought him into conflict. But the qualities also made him one of the most influential, entertaining and patient-facing physicians of his generation.

His professional contributions include jointly founding the European School of Oncology (ESO) in 1982 and the European prostate cancer patient coalition Europa Uomo in 2002. Alberto Costa, now ESO Chief Executive Officer and also a joint founder of both organisations, remembers how ‘big brother’ Louis was the first to volunteer to provide support for both organisations. “It was a time when nobody seemed to care about prostate cancer, but he thought we should be brave enough to found Europa Uomo.”

Louis Denis was also a founding member of the Genito-Urinary Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), and served as both Treasurer and President of the EORTC from 1988 to 1991. He helped launch the European Journal of Cancer in 1990 and was Secretary General of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) in 2000. He was Head of Urology at Antwerp Hospitals, Professor of Urology at the Free University of Brussels, and Director of the multidisciplinary Oncology Centre Antwerp from 1998 until the end of his life.

His career also included a fair amount of adventure. In 1964, as Chief of Urology at Antwerp Military Hospital, he was summoned to help as a field surgeon when Belgian paratroopers rescued over 700 European and American hostages in what was then Stanleyville, in the Belgian Congo (now Kisangani in the Democratic Republic of the Congo). He was awarded several Belgian civil honours.

Throughout it all, his driving priority was that doctors should do all they could to put patients at the centre of treatment. He may not have been the first to say, “A physician should treat the person, not just the disease,” but it could have been his motto.

Speaking to Cancer World in 2004, he said, “Our first aim it to make clear to patients that we see them as independent individuals and they should not be afraid to talk to their doctors as equals.”

Telling it as it is in prostate cancer

It is perhaps his work with and for men with prostate cancer for which he will be most fondly remembered. “Ounce for ounce or gramme for gramme, the prostate gland is the most troublesome piece of tissue in a man’s body,” he once said, typically getting straight to the point. He was acutely aware from early in his career of the troubles that many men endured through diagnosis, treatment and treatment after-effects.

He was a strong advocate of specialist prostate cancer units utilising the expertise of a multidisciplinary team. And he was outspoken on the dangers of overtreating men with prostate cancer, believing that screening had to be carried out responsibly because of the dangers of getting drawn into unnecessary treatments and their side effects. “Being told you have cancer can destroy your life, even though in the end you may die with the cancer rather than because of it,” he said.

His already patient-orientated perspective gained a new focus when he was diagnosed with prostate cancer himself. Having long argued that urologists should be honest about the side effects of treatment, he admitted that his own radiotherapy had produced depths of exhaustion that he never expected. And he was honest that he had “fallen into the trap” of overtreatment himself, having ended up with impaired bladder control after being persuaded, against his better judgement, to accept an extra dose. “As a patient, I must confess I find hospitals depressing places,” he said.

The need for better knowledge about the efficacy of different screening techniques was tantamount, he believed, and he was the international co-ordinator of the highly influential European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC), investigating the influence of PSA testing on prostate cancer mortality. This occupied him to the end of his life. At a Europa Uomo General Assembly meeting held just weeks before his death, he stepped down as an ex-officio Board member, but made clear that this was not the end of his involvement: his work on ERSPC would continue, linking closely with Europa Uomo’s EUPROMS quality of life studies.

At that meeting, many who had worked with Louis Denis paid tribute to his warmth, sense of humour, compassion and dedication to supporting Europa Uomo with his knowledge and contacts. All described him as a friend: even when Louis had disagreements, they often ended in laughter. “There were no ‘yes men’ in Louis Denis’s Europa Uomo,” said Board member John Dowling.

At the end of that meeting in June, Louis Denis wished Europa Uomo well, and urged its members to do what one suspects he did throughout his life, for all the seriousness of his mission to improve lives. “Have fun,” he said. “Because that is the most important thing. Keep laughing with each other.”

In his 2004 profile in Cancer World, Louis Denis said he had always been conscious of his own mortality and that his illness had not made him afraid of death. He wanted champagne at his funeral and for his friends to remember him as a free-thinking man. “I see no reason to hang on needlessly,” he said. “At this age one should have the maturity to view cancer as a challenge, and as an opportunity to surpass oneself, to look at things differently and to acknowledge forces greater than oneself.”