How do you get the greatest impact for patients from the sum total of a nation’s clinical cancer research efforts? The answer that the UK came up with at the start of the new millennium was the National Cancer Research Institute – a body designed to bring collaboration and partnership into cancer research, to reduce duplication and unnecessary competition, to enable informal peer review at an early stage and to raise scientific standards.

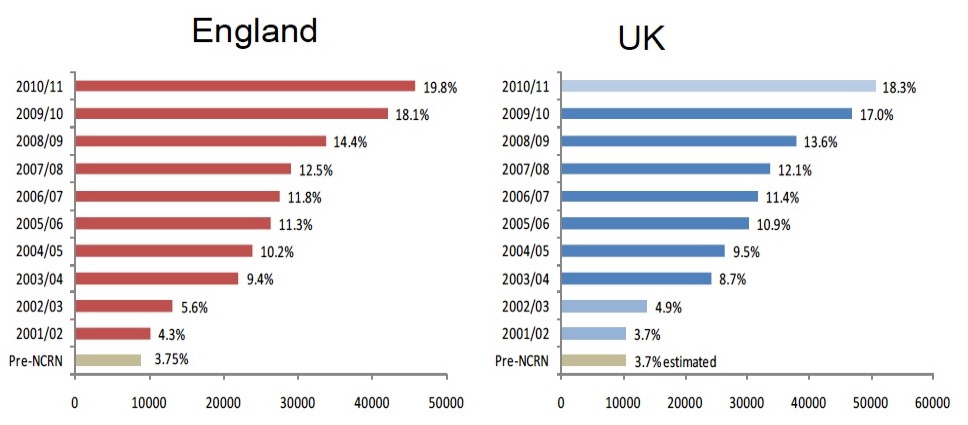

For more than a decade, Britain’s clinical cancer research environment was the envy of all Europe. Rates of participation in clinical trials soared, oncology units at hospitals across the country developed their research capacity with all the collateral benefits that brings, patients were supported to bring their experiences and priorities into the process of setting research agendas, and complex issues requiring service-wide changes were addressed. Duplication, competition and fragmentation dramatically reduced.

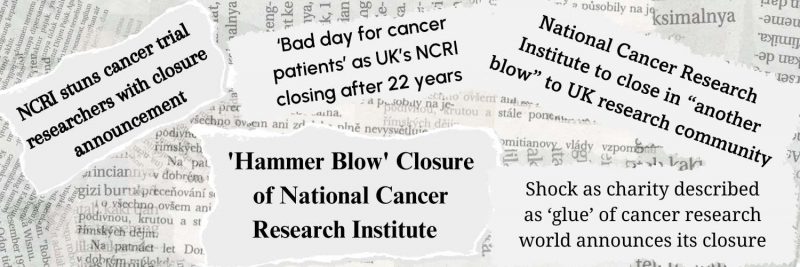

That was all achieved with minimal cost and bureaucracy. The value of NCRI’s contribution was never in question within the cancer community. While many of us who worked with NCRI had seen the writing on the wall for some time, the announcement of its closure, made in late June, was met with shock and anger, as can be seen from the reactions of senior researchers published on the Science Media Centre website, and this article in The Lancet – one of multiple articles published across a wide range of platforms in response to the unwelcome news.

A better research environment

The NCRI was created by the Department of Health in 2001 as a ‘hands-off’ agency. It consisted of a small team focused on understanding the research landscape and how it might be re-shaped, gap analysis, identifying and researching priority areas for future research, data gathering and analysis, and working to improve public awareness of research. The ‘institute’ badge is deceptive. There was no grand building, indeed there was no corporate entity at all. In practice it relied on Cancer Research UK facilities, and its staff were contracted as employees of CRUK. I joined the NCRI structure in my capacity as a patient expert in 2002, shortly after it was founded.

The Institute brought together the major funders of research from public and charitable sectors to share priorities, develop common policy, and provide the Department of Health with a means of overseeing the National Cancer Research Network – a government funded project set up in the same year to develop the front-line resources which would build the capacity and capability of the NHS to provide cancer clinical studies to patients.

This was no small task. I watched as local networks of key individuals were chosen and given budgets, supported with training for new staff, linked to the evolving Local Improvement networks established by the NHS Cancer Director, and extensively supported as their local clinicians identified studies they wished to make available to their patients.

At the core of National Cancer Research Network were the Clinical Studies Groups, which bore the NCRI name. These had a foundation in earlier work but had been under-resourced. Bringing them into the structure gave them clear purpose and authority. Their role was to identify clinical studies of a high quality which were relevant to patient needs and approve them for funders to consider supporting within the NHS. I joined the NCRI Sarcoma Clinical Studies Group in 2002, and by default became a member of the Consumer Liaison Group – the group of patients involved with NCRI and National Cancer Research Network.

NCRI had oversight of all this work.

- An analysis of partner spend using the Common Scientific Outline. This dataset now covers 20 years of cancer research. It has been used to identify gaps where increased funding would add value, and to help partners recognise each other’s contribution in less public areas of science.

- An investigation into Supportive and Palliative Care, which resulted in a multi-million pound six-year capacity-building project.

- A look at cancer prevention, which opened the way for a ten-year National Prevention Research Initiative across a range of chronic and acute illnesses, backed by funding of £30m ($38m).

- A re-energising of prostate cancer research, after NCRI profiled what was happening in the field and described what everyone agreed should be happening.

- A similar approach to lung cancer a few years later, which had a similar effect.

- Research looking at the difference in hospital performance between places where clinicians were/were not actively involved in research. The benefit of research integrated into routine care was clear, and the findings were used to great effect to advocate for promoting clinical cancer research not just in the UK but also across Europe.

Meanwhile the National Cancer Research Network had met its ambitious Treasury-set targets well ahead of time, and the integration of cancer research into cancer care meant that almost every patient had access to research. The development of the Experimental Cancer Medicine Centres from 2007 had created a third leg to development work and the leadership of this fell to Cancer Research UK.

Embedding research in clinical practice 2001–2011

A pioneer of patient involvement

In the midst of all this, patient involvement had been developing through the Consumer Liaison Group. Cancer patient advocacy was still in its infancy at the time. The NCRI was pioneering in recognising the essential role patient experts have to play in helping inform research agendas, and in providing structures and resources to support them to do that work.

The initial aim in 2001 had been to see two patients in each tumour Studies Group, plus representation of the patient voice in other areas as well. When I joined in 2002, there were 14 members in the Consumer Liaison Group. I chaired the Group for three years, starting in 2004. By the time my term ended, membership had risen to nearly 50; some who had served their stated term on a Study Group continued in associated membership, offering advice and experience where it was needed.

Unpicking the gains

The NCRI was becoming embedded in the development of Britain’s cancer services but, with the election of a new government in 2010, it all began to change. We lost the National Cancer Research Network, with its role shifting to the National Institute of Health Research. Alongside this came damaging closures of working groups in the NHS, including all the local cancer partnerships, which were focused on improving local services, and the parallel research networks, which fostered sharing and training. Local structures which ironed out problems, empowered sharing, enabled mutual improvement, all disappeared.

What also disappeared, almost invisibly, was the NCRI’s role as a policy-informer and influencer. The new government knew where it was going, and consultation was nominal. I even heard it said that NCRI’s role had been fulfilled, and that partnership development and collaborative working was now embedded in the cancer research landscape, making the NCRI redundant.

Little effort was made to counter this view, or to highlight how fragile these gains really were. The capability of the NCRI team had already been eroded. There were fewer experienced staff and it was noticeable at meetings that the patients (consumers) present often had a wider experience and were better informed than some of the NCRI staff present. Cancer Research UK – a research charity, and not a public body – took on a more prominent role as policy influencer and strategic adviser to the NHS and government.

The major change for NCRI took place in 2015. The Government decided the Institute would no longer exist under the Department of Health, despite clear evidence that it was needed, not least to provide a firm basis for the Clinical Study Groups and the patient group (by now renamed Consumer Forum). A decision was made to set it up instead as a charity, with a new remit and an independent Board of Trustees.

Its primary objective remained unchanged: to promote collaboration in cancer research. Its resources and the research environment, however, were very different from 15 years earlier.

- Collaboration, cutting out competition, avoiding duplication, enabling like minds to work together

- Influential studies on gaps in research, opportunities, new ways of working – a missed opportunity in recent years

- Finding simple ways to unlock complex problems (eg. CTRad)

- Funded initiatives addressing structural needs in research

- Early Career Researchers forum, filling an identified gap in academic provision

- The Consumer/Advocacy Forum, a unique and widely envied resource

- Close collaboration with cancer service development – eroded in recent years

- The context of collaboration

- The ability to bring the whole community together when needed

- The Consumer/Advocacy Forum if it cannot be found a home

- An independent body which can represent cancer research

What we lost

The NCRI was able to clock up some notable achievements in its reincarnation as a charity, driven principally by the patients active within the Consumer Forum. Membership was now around 140, many of whom had by now developed considerable experience and expertise. The Forum developed the ‘Dragons’ Den’ concept for study review, which has been widely welcomed and is now extensively copied. It also picked up on the earlier work on survivorship and worked with Cochrane on developing the research priorities for Living With and Beyond Cancer. These were widely praised when published and provided a theme for all the Study Groups to consider.

The development of the Clinical and Translational Radiotherapy Research working group (CTRad) was another great success story. Proton beam research was badly needed, for instance, but efforts had been half-hearted and fragmented around the world. Under CTRad in the UK it came together, with clear direction and purpose. And just as the biomarker revolution was getting underway, development of the NCRI Cellular and Molecular Pathology (CMPath) group, and the increased representation of early-stage scientists in the Research Studies Groups, improved understanding of the rationale for many clinical studies.

What was missing from the new NCRI, however, was the ‘voice’. Once, it had spoken for cancer research, contributing expertise from the huge range of scientists, clinicians, nurses, researchers, and patients who were involved. It developed policy papers, examined developing issues and considered their influence on research, and looked for gaps which should be addressed.

This work was no longer happening. The new NCRI Board was invisible, did not publish its minutes, its members did not speak in public as NCRI Board members, and consultation with those involved in the organisation’s activities was minimal. The executive team was anonymous, inwardly focused and kept changing. The annual NCRI Conference, once a stand-out major event in the calendar, became a liability with the withdrawal of pharma.

It was the decision of Cancer Research UK to extract itself from NCRI that dealt the final blow. No-one has been found willing to offer funding to enable even a slimmed down NCRI to pursue its remit as an independent body promoting collaboration in cancer research.

As it is a charity, the Trustees now have the obligation to transfer identifiable assets into new homes that meet the charitable aims of NCRI. Those assets are the Consumer/Advocacy Forum – probably the most capable body of cancer patients involved in research, the Early Career Researchers Forum – which has over 500 members – and the Research Study Groups. It is anticipated that many of the Groups will be re-homed by relevant charities, but some of the cross-cutting themed groups, such as the successful Clinical and Translational Radiotherapy Research Study Group, may find that difficult.

So, it is not all over yet, and there is probably some shouting to come.

The UK is in danger of losing the true power of the patient voice in cancer research. It will be there in small ways, in individual studies and programmes, but no-one will be addressing the whole clinical agenda, taking the oversight which moves matters forward. The voice of the critical friend will be silenced, allowing vested interests to drive their own agendas, while the rational view from those who are most affected will be absent. This voice is essential to prevent UK cancer research declining further in influence, and those most affected by its loss will be UK patients.

1 comment

Feel like “hope “ for Cancer patients as been taken away

Comments are closed.