When I first connected with Professor Fedro Peccatori, the line between us was anything but fixed: he was calling from a moving train between Padova to Milan, between obligations. Yet the instability of the connection seemed fitting. His entire career has been about navigating transitions—between disciplines, between life and illness, between science and humanity.

Peccatori, now a globally respected oncologist and educator, insists he never planned it this way.

“I always wanted to be a doctor,” he tells me, “but oncology came serendipitously.”

Building a Career of Crossroads

He was training in gynecology in Milan, than in Monza in the late 1980s when a visit to Bellinzona placed him in the orbit of Franco Cavalli and Cristiana Sessa. “They had the intuition,” he recalls. “All the specialists around one table, each case considered in its whole context. Even the nurses spoke first sometimes—they knew the patient’s social story.”Decades before tumor boards became routine, Peccatori witnessed the embryo of multidisciplinary care: oncology not as a solo sport, but as an orchestra. It changed the scale of his thinking.

After completing his degree at the University of Milan in 1988, Peccatori deepened his training with a PhD at Sapienza University in Rome. He spent research years in the Netherlands, where, as he recalls, “the cultural differences were not dramatic, but the scientific approach was. It taught me how to ask questions differently.” As a young fellow at the Mario Negri Institute under Silvio Garattini, he had already gained a grounding in research that would shape the rest of his career.

Back in Milan, at the Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori (INT), he walked straight into the hardest questions of that era: high-dose chemotherapy in breast cancer that looked promising until the data said otherwise. “INT was the best place to test and to stop,” he says. That small verb—stop—says much about his method. For Peccatori, rigor is as much about restraint as it is about invention.

By 1995, he crossed town to the Istituto Europeo di Oncologia (IEO) where he would truly build his legacy. It was there that his clinical focus on fertility, pregnancy, and young adults began to crystallize.“It was something new, something deeply tied to patients’ futures,” he explains.

A Future Patients Could Still Claim

In the 1990s, few spoke about fertility after cancer. For men, sperm banking was known and available. For women, options were complicated and rarely discussed and often introduced too late. Peccatori and his colleagues began to make fertility preservation part of oncology, not an afterthought.

“For many young women, fertility preservation wasn’t about a child immediately,” he says. “It was about a future they could still name.”

Since 2011, Peccatori has led the Fertility and Procreation in Oncology Unit at IEO in Milan, turning what was once a fragile hope into an integral part of cancer care.

Cancer in Pregnancy

Perhaps the next big step in his career, maybe the most delicate one came when he and his team began treating cancer in pregnancy. For decades, the default response had been termination.

“We didn’t know what was possible,” he said. “Could we do surgery safely? Could we give chemotherapy without harming the baby?”

He remembers a 36-year-old pregnant woman with neuroblastoma, a tumor almost never seen by adult oncologists. “Everyone came,” he says simply. “Pediatric oncologists, obstetricians, pathologists. We asked: how many weeks can we safely give her? How do we balance the mother and the child? The solution was not a miracle so much as choreography: buy weeks safely, monitor closely, match tempo to biology and gestation. “The victory,” he suggests, “was time—time converted into possibility.”

Today, IEO and Mangiagalli in Milan are recognized as referral centers for cancer during pregnancy, but Peccatori is quick to point out that it was never a solo effort. “You never do something by yourself in medicine. It was always cooperation—oncologists, pathologists, obstetricians, neonatologists and, most of all, the patients.”For Peccatori, these cases embody both the beauty and the difficulty of his work. “The most rewarding part is giving women the possibility of a future—beyond cancer, with family, with life. The hardest part? Accepting that sometimes medicine cannot go as far as we wish.”

The Land In-Between: Adolescents and Young Adults

The third chapter of his work focuses on adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology— patients, too old for pediatric wards, too young for adult clinics, group too often lost “in the land in-between,” as he calls it. “Their outcomes are worse than children’s, worse than older adults”.

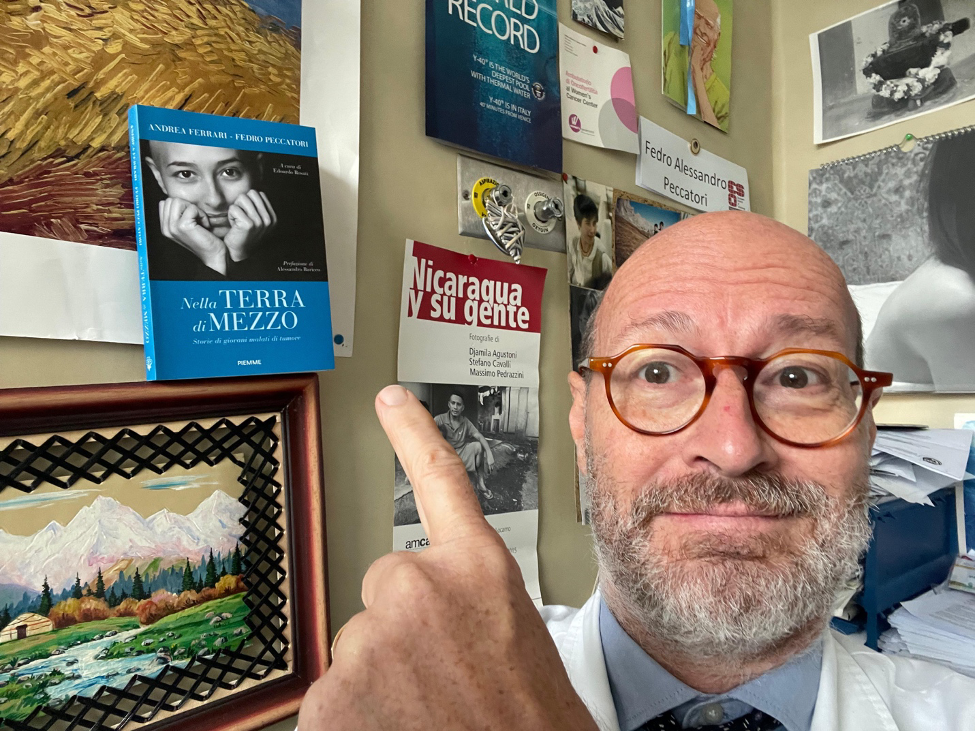

Together with colleagues like Andrea Ferrari, he built initiatives at both the Italian and European levels. They developed guidelines, created networks, and advocated for these patients who, in his words, “are not just statistics—they are young people who deserve someone to listen.”

Listening is a word he returns to often. “Patience, patience, patience,” he says, almost like a mantra. “The ability to listen is as important as any drug we prescribe.” Young people wanted explanations, choices, honesty. They wanted doctors who treated not just their cancer, but their lives—school, work, relationships.

A Teacher, a Mentor, a Builder

Teaching, Peccatori admits, came “a little by chance, like many things in my life.” First a fellow, then eventually Scientific Director of the European School of Oncology (ESO), he spent ten years shaping programs that would become the backbone of European oncology education. “I owe a special thank you to Alberto Costa, who wanted me to join ESO. We made a very nice trip together, and I hope I gave my contribution, however humbly, to improving the quality of oncology education in Europe.”

What made it so important, he explains, is that oncology itself is still young. “It hasn’t always been its own discipline. In the past, organ specialists treated their cancers—pulmonologists for lung, gynecologists for gynecological malignancies, surgeons for many others. Building oncology meant not only building training programs, but building identity.”

Through masterclasses, clinical training centers, and specialized courses, he helped generations of young oncologists learn not only the science but also the posture of the profession. “Mentorship is not just about techniques,” he says. “It’s the way you approach a patient, the way you listen, the way you carry yourself as a doctor. That is the legacy.”

He also remembers the influence of Umberto Veronesi, founder of the Istituto Europeo di Oncologia. “Veronesi had this fantastic and unique personality—charisma with patients, but also with collaborators. He showed us that science and humanity can walk together.”

Fatherhood, Mountains, and the Future

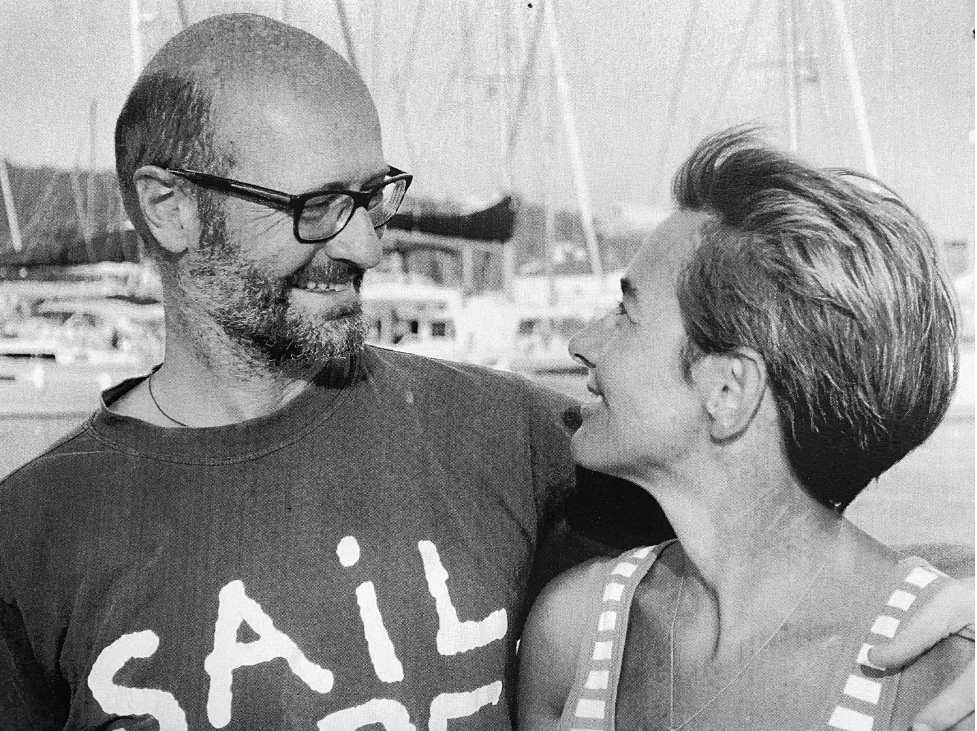

Peccatori is also a father of five and husband of a pediatrician. Two of their children are doctors, one a pediatrician. “We tried to stay neutral,” he laughs. “But maybe, unconsciously, they absorbed something from both their parents.” He speaks of role modeling not only in families but in institutions. “Being a model means showing that you can be a good doctor, but also a good father, a good partner. Investing in all those things is a good investment.”

“‘Retirement?’ he repeated when I asked. ‘I think there is a time for everything—a time to study, a time to work, and a time to care for yourself. For me, it will be the mountains. I imagine nature, quiet, reconciliation. But I will never abandon what shaped my life. Even then, I will stay connected to research, to education. There is still so much to do.’”

Lessons for the Next Generation

When I ask what advice he would give to his younger self—or to the many young oncologists who look up to him—his answer is immediate:

“Curiosity. Humbleness. And a little bit of boldness. Be courageous in your choices. Don’t say: ‘This is too much for me, I will never succeed.’ Try. Give yourself the chance. Sometimes it’s about persistence, sometimes about courage. But always about believing in your future.”

Optimism, for him, is not naïveté—it is discipline. A deliberate choice to believe in people, in medicine, and in life beyond cancer.

In the end, what defines Fedro Peccatori is not only his scientific contributions but the humanity he brings to every interaction. “Patients are not only cancer patients,” he tells me. “They are persons, with their own priorities. Our job is to listen, to guide, to walk with them.”

On a train, between cities, between moments, his voice carries the calm conviction of someone who has devoted his life not only to curing disease, but to honoring life. And perhaps that is his greatest lesson for all of us: that oncology, at its heart, is not only science—it is a profoundly human art.