Q. Surgery tends to be a bigger issue for older people, and physicians need reliable guidance on who is likely to benefit and who could be harmed. You looked at selection practices and outcomes at 56 breast units across the UK. What did you find?

A. The Bridging the Age Gap in Breast Cancer study recruited nearly 3,500 women over the age of 70, who were newly diagnosed with operable breast cancer. We wanted to collect very detailed data about their level of baseline fitness so we could understand treatment selection and age- and health-stratified outcomes. We therefore organised a prospective observational study, planning to adjust for bias by use of propensity score matching.

A key area of enquiry concerned elucidating the factors associated with selecting patients in the age group either for surgery or for primary endocrine treatment, and the related outcomes. Of 2,854 women with oestrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer, 82% had surgery and 18% had primary endocrine therapy. We found that women receiving primary endocrine treatment were older and less fit than those treated with surgery.

In terms of outcomes, with a median follow up of 52 months, an unadjusted analysis showed that all-cause mortality and mortality from breast cancer were both lower in women having surgery (HR=0.27, 95%CI 0.23‒0.33, P<0.001 and HR=0.41, 95%CI 0.29‒0.58, P<0.001, respectively). However, when we performed very specific propensity score matching for age, tumour characteristics and health status, whilst all-cause mortality was still slightly better with surgery (denoting imperfect matching) (HR=0.72, 95%CI 0.53‒0.98, P=0.04), breast cancer specific mortality was no longer significantly different (HR=0.74, 95%CI 0.40‒1.37, P=0.34).

We also looked in detail at chemotherapy outcomes in these women, using the same methodology. Chemotherapy was given to almost 28% (306/1,100) of fit patients who had a high breast cancer recurrence risk. Comparison of chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy demonstrated reduced metastatic recurrence risk in high-risk patients, when comparing unmatched patients (HR=0.36, 95%CI 0.19‒0.68) and also when comparing propensity-score-matched patients (adjusted HR 0.43, 95%CI 0.20‒0.92). However, no benefit to overall survival or breast-cancer-specific survival was found in either group. Unplanned subgroup analysis found that chemotherapy improved overall and breast-cancer-specific survival in women with ER-negative cancer (HR=0.20, 95%CI 0.08‒0.49, and HR=0.12, 95%CI 0.03‒0.44, respectively).

In both the surgery and the chemotherapy analyses, we also looked at the quality of life. In both, more aggressive treatment had negative impacts on quality of life, but these changes were transient and largely resolved after two years of follow up.

Q. What are the key messages from the Bridging the Age Gap study?

A. We concluded that surgery should be advised for the majority of women aged over 70, but in women over the age of 85‒90, especially for those in poor health, consideration of primary endocrine therapy may be appropriate. For the chemotherapy analysis, we concluded that chemotherapy was associated with reduced risk of metastatic recurrence, but survival benefits were only seen in patients with ER-negative cancer. Quality-of-life impacts were significant but transient. This should be taken into account when discussing treatment options with older women.

Q. Part of the study involved developing an online decision support tool to help reach the best decisions on treatment options. Can you tell us about that?

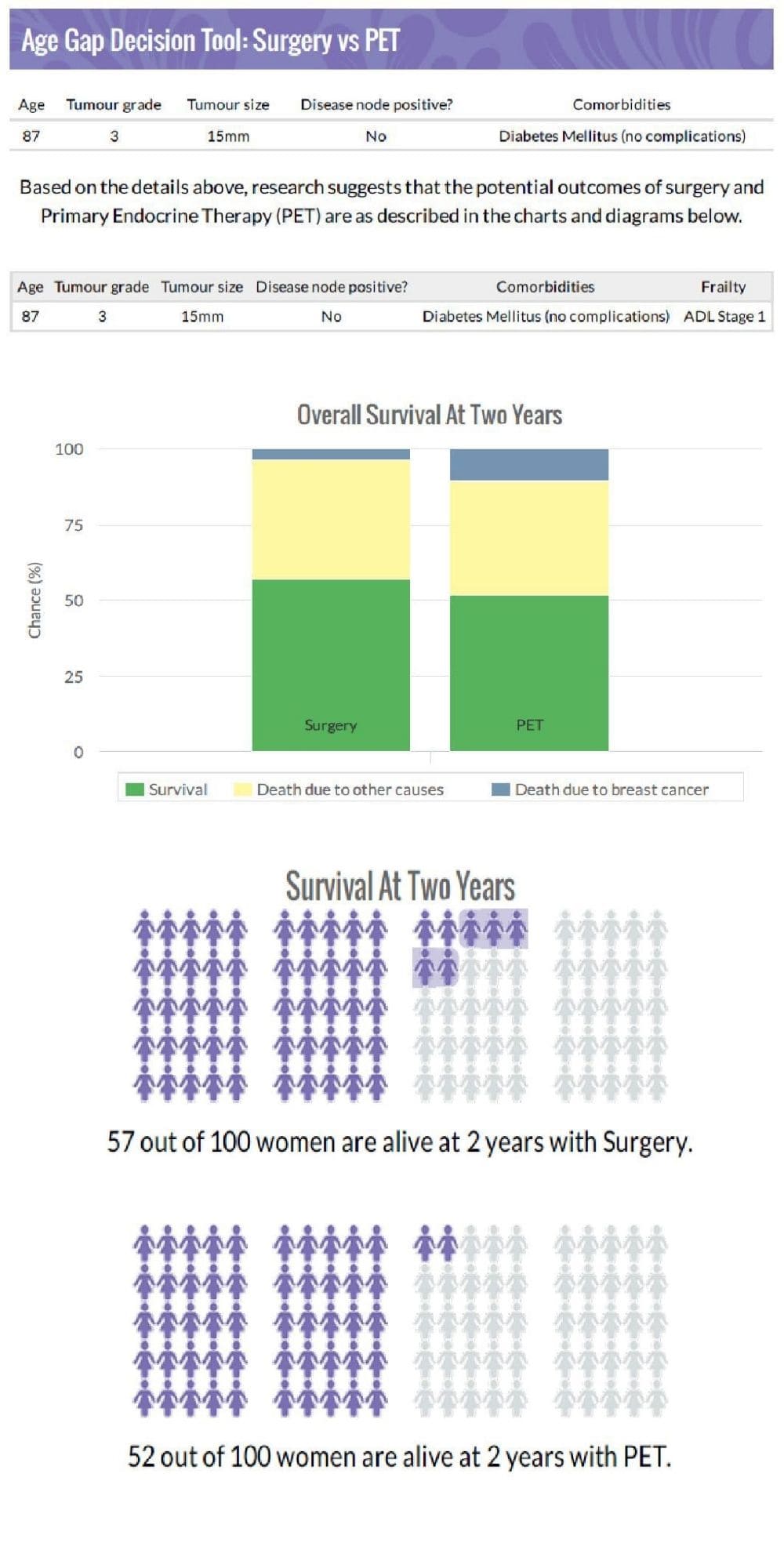

A. The Age Gap decision tool is a decision aid for use with women who have been offered surgery or primary endocrine therapy, or women who have had surgery and are now facing a decision about whether to have chemotherapy. The online tool can be used to calculate potential outcomes from different options, stratified for age, cancer (grade, size nodal status) and fitness. The tool was carefully developed with input from older women to ensure it met their informational needs and was designed to meet their preferred options for data display and terminology.

The tool was embedded into the second half of the Age Gap project as a cluster randomised trial, and we found that use of the tool modified treatment selection and improved patient knowledge. We were surprised that use of the tool tended to make women more likely to choose a more conservative option ‒ presumably when they saw that survival rates differed by only relatively small amounts.

The online tool was released for wider use in the Spring of 2020, and, in its first year, was accessed over 10,000 times in more than 70 countries. We have had interest from groups in France and Canada to validate the tool for use in their own populations. We are currently developing the tool to add quality of life and adverse event data outputs alongside the survival outputs it already contains. The data from the Age Gap study will be used to develop age and health stratified outcome models for these metrics. We hope this will go live at the end of 2022.

Q. What were the key motivations behind launching the study?

A. We knew that some centres in the UK were offering surgery to women who were very frail and unfit, who were unlikely to benefit, while at other centres, relatively fit older women were being denied surgery, even though they would undoubtedly develop progression within their expected lifetime. So we wanted to try to develop advisory thresholds for older women who might not benefit from aggressive primary treatment due to their age, frailty, comorbidity and disease biology, to help minimise over- and under-treatment in this age group. Existing guidelines such as those by the International Society for Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) are rather imprecise, so we needed detailed health and fitness data at baseline so we could perform stratified analysis. The Age Gap dataset then helped us to develop the online tool which can assist in this decision making process.

We also wanted to explore these differences in rates of surgery versus primary endocrine therapy and differences in rates of chemotherapy across the UK. We analysed the data from the study and confirmed that rates do vary more than can be explained by case mix. We went on to study the reasons for this variation by conducting some qualitative research and a wider questionnaire study of UK breast professionals to explore the reasons for this variation. The questionnaire included a discrete choice instrument, which presents people with a set of clinical scenarios with five variables and looks at how these sway treatment choices. These studies clearly showed that clinicians have different thresholds for how they allocate women to treatments, with age being a significant factor.

Q. It is not easy to enrol nearly 3,500 patients in a study, and it is rarely attempted in that age group. How did you do it?

A. We had previously tried to recruit to randomised trials in this age group to look at both the surgery versus primary endocrine therapy question (ESTEEM trial) and the use of adjuvant chemotherapy (ACTION trial). Neither randomised trial was successful due to poor recruitment, which is often felt to be an issue in this age group.

So we were pleasantly surprised that our older women were very positive about taking part in the Bridging the Age Gap study. We started recruitment in 2013 and completed it in 2018, recruiting at 56 sites across the UK.

The trial had been specially designed to be user-friendly for older women. The study was observational, with treatment as normal, but women were asked to complete quite a lot of questionnaires, which took time to do. We allowed women to elect whether they wished to complete the quality of life questionnaires, to keep the burden of participation as low as possible. We also permitted many of the follow up visits to be done by telephone and could post the questionnaires out. We also wanted to recruit women with dementia, so we designed the trial such that a proxy could consent on behalf of women who lacked capacity to consent for themselves.

Overall, the ratio of women screened for the trial to those recruited was about 50% which is very good. Retention rates were also excellent, with very few women withdrawing. We did notice that we slightly over-recruited the younger end of the over-70 age range, and slightly under-recruited at the older end, but our oldest recruit was 102, so we are very pleased with what we achieved.

Q. The trial is exclusively a UK study. Do you expect its results to have an impact on other countries? Did you receive enquiries from other centres?

A. We only recruited in the UK, as a key aim was to explore the differences in rates of surgery versus primary endocrine therapy and differences in rates of chemotherapy across the UK, which have long been a cause for concern. We have had interest in the study from France, Canada, the Netherlands and the USA, and are collaborating with the group from Leiden, to compare our data with their own similar dataset (the CLIMB study) to see where practice and outcomes differ between the UK and the Netherlands. This analysis should be completed later in 2021.

Q. Was surgery in this elderly population mainly mastectomy or conservative procedures?

A. Data on the type of surgery undergone by the women in the study have been published. Of 2,854 surgical procedures, 40% underwent mastectomy and 60% breast conservation. Increasing age, tumour size, and nodal status were all significantly associated with receipt of mastectomy. This is likely to be linked to the lack of screening and reduced breast awareness in older women, resulting in larger tumours with a higher risk of node positivity.

Very few women underwent reconstruction in this over-70 age group ‒ only 2.8% had post-mastectomy reconstruction, compared with a rate of 20% recorded in published series in the UK across all ages. Outcomes were good, with no deaths directly attributable to surgery, although the risk of adverse events was moderate. Excluding seromas, which we regard as inevitable after breast surgery, there were 761 complications after 551/2,854 procedures. The vast majority were local complications and not classed as severe. Only 59/2,854 procedures (2.1%) had systemic complications such as stroke, cardiorespiratory problems or deep vein thrombosis. Complications were more likely after major surgery (mastectomy or axillary clearance compared with breast conserving surgery or sentinel lymph node biopsy). This suggests that, for the majority of older women, surgery is safe and well tolerated.

However we also measured quality of life after surgery and found that it does have a negative impact on some domains of quality of life. Of particular note, compared with sentinel lymph node biopsy, axillary clearance caused a 6-point reduction in the global health score of the EORTC QLQ C30 tool, as well as greater arm symptoms. Similarly, mastectomy had a greater negative impact than breast conserving surgery. In the early post-operative period, mean role function declined by 5.2 points for women treated with primary endocrine therapy, compared with 16 points for surgery. Pain scores increased by 1.8 for primary endocrine therapy compared with 7.1 for surgery plus endocrine therapy, and breast symptoms increased by 0.7 points for primary endocrine therapy compared to 12.7 for surgery followed by endocrine therapy.

The overall burden of illness increased by 4 points in the primary endocrine therapy group compared to 10.1 for surgery plus endocrine therapy. By 24 months many of these differences were largely back to baseline levels, but with several domains treatment had a more lasting negative impact. Changes were more notable when comparing major surgery (mastectomy or axillary clearance) with primary endocrine therapy.

We conclude that surgery is generally safe and well tolerated, but it does have a ‒ largely transient ‒ negative impact on quality of life, and for the frailest older women may not be needed. Selection for treatment may be supported by use of the Age Gap decision tool.

The Bridging the Age Gap study was funded by a programme grant from the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).

About Lynda Wyld

Lynda Wyld, Professor of Surgical Oncology at the University of Sheffield and Honorary Consultant Surgeon at the Jasmine Breast Centre, Doncaster, England, is Chief Investigator of the Bridging the Age Gap study. She has served as President of the British Association for Surgical Oncology, Board Member of the European Society of Mastology (EUSOMA), Chair of the Education and Training Committee of the European Society of Surgical Oncology (ESSO), and Chair of the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) Surgical Oncology exam board. She has published extensively on managing breast cancer in older women.