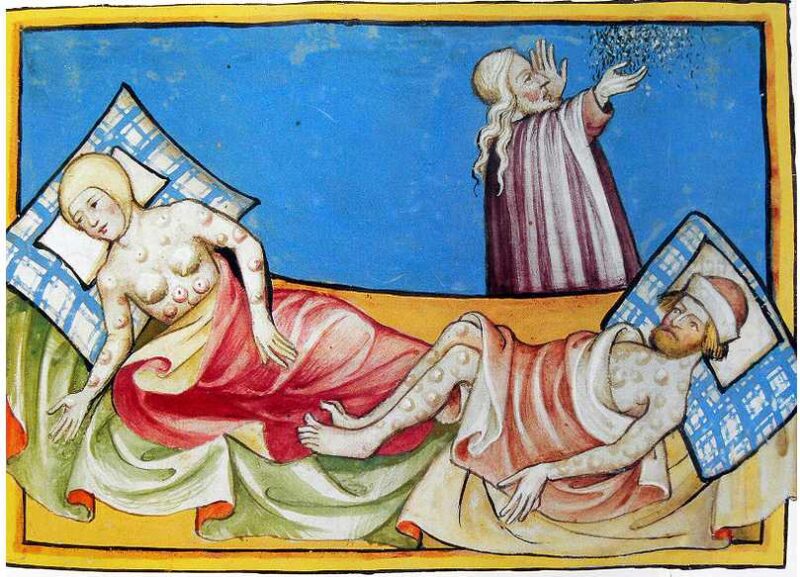

‘Contagion’ seems like an outdated word in medicine. Transmissible illnesses are no longer described as ‘contagious’, they are ‘infectious’, and we study ‘infective’ agents. Contagion is a term evocative of the medical past. Talking and writing about contagion evokes the musty walls of ancient sanatoriums, wailing voices in dimly lit corridors of hospitales, the ‘natural philosophers’ of European anciens régimes who, when facing the bubonic plague, spoke of stars and constellations.

More recently, director Steven Soderbergh chose ‘contagion’ as the theme for his eponymous film that tells the story of the outbreak of a fast-spreading deadly virus transmitted by respiratory droplets. With the tagline “Nothing spreads faster than fear,” it depicts the urgent attempts of medical researchers and public health officers to identify and contain the infection, and the breakdown of social order as people begin to panic.

Contagion, infection, contamination…

But ‘contagion’ and also ‘contamination’ can also convey a more positive sense. Human sciences have long stressed the importance of creative contagion in relation to ideas, literature, culture. Ancient ghosts from seemingly lost plagues and new sparks of knowledge are both implied.

Epidemiologists have been studying aspects of the coronavirus pandemic from an empirical standpoint, as they have followed the spread of Covid across Europe and other continents, sharply noting how the most efficient ally of the new disease has been the initial indifference toward the first news about the facts in Wuhan. Humanity knew this type of pandemic was coming; the scenario had even been popularised in David Quammen’s award-winning book Spillover, published in 2012, which warned that the ‘next big one’, a ‘new Ebola’ or some kind of ‘neo-SARS’ was brewing at the edge of Western civilization. Unfortunately, this kind of foreseeing ‒ sometimes more literary and journalistic than epidemiologic ‒ did not find enough of an echo in science and administration. For some reasons even the most advanced and technological countries came unprepared to the new danger.

Contagion is not merely an individual fact

In Italy ‒ the first country after China to be heavily affected ‒ when the virus first stuck, disbelief and confused thinking ran wild. An initial storm of misinformation ‒ claims that COVID-19 is merely a seasonal flu, for instance, or that random medicines can prevent it ‒ slowly cleared away, leaving in its wake fear, anxiety, and panic.

Besides the ‘biological damage’ of infection, psychiatric symptoms have to be evaluated, giving insights that could help us face this new insidious threat to our health.

The contagion is not merely an individual fact. The problem lies with the scale. There is a social significance of COVID-19 effects. Of note is a very interesting there regarding the effectiveness of hygiene and protection ‒ one of the most ‘banal treasures’ of classic medicine. With the current uncertainties surrounding masks and gloves, and the comparative effectiveness of alcohol, alcoholic gels and soap for hand washing, the hard-gained scientific benefits of fundamental concepts of hygiene could get lost in the epistemic murk that characterises the postmodern society.

Most notably, the pandemic process has crippled national healthcare systems. Health workers in general, and physicians in particular, have been on the front line ‒ initially with little to no support from hospital managements. Shortages of personal protective equipment became a focus of attention for healthcare organisations and policy makers in Italy and then later in the US. Healthcare workers have been exploited by the media, being designated ‘national heroes’. They had to face a new threat, with apparently unpredictable odds, and carried the burden of working excessive hours for sustained periods, assisting with a large number of end-of-life events ‒ their own among them. What a terrible payoff, as heroes are not allowed to tell their story ‒ and there is much to hear about, because we would argue that this situation was at least partially foreseeable, and the healthcare system could have been better prepared.

In the longer term, it may be the psychopathologic issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic that leave the lasting legacy. Continuing damage will be done by the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown, beyond what can be described in terms of ‘anxiety’ and ‘panic attacks’. A new epidemic looms on the horizon, and this time it concerns a psychological state. Its name is familiar to war veterans, and also oncologists, as it is a not rare after effect of cancer: namely, post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD).

A new epidemic looms on the horizon, and this time it concerns a psychological state

Life threatening illnesses have been recognised as a stressor that can precipitate PTSD ‒ a condition that leads to symptoms such as recurrent and unwanted memories of the traumatic event, flashbacks, loss of sleep, severe emotional distress, behavioural disorders, self-harming up to suicidal thoughts and antisocial acts. PTSD can be just as lethal as many other illnesses, and the risk of having such a widespread stressor among the national population is self-evident. Healthcare workers, survivors, parents of COVID-19 victims, and public service workers are among those most at risk of developing this condition. The precarious state of many national economies, which face an impending economic crisis leading to loss of work and welfare, means that this stressor may well be acting on a very large number of people, advancing even otherwise stable conditions.

The pandemic leads to new questions. What about the world after this new illness? How can we manage the transition from lockdown to new, less strict, measures of containment? How can we reach and treat mental distress?

We must recruit some disciplines bordering that of psychopathology, the great tree of cultural knowledge represented by philosophy and its subdisciplines. Philosophers aim to show how contagion is a ‘total concept’, in the anthropological sense. While disease is a biological fact, the experience of it is clearly a subjective one. As scientists, we might be tempted to focus on the biochemistry, virology and immunology. But if we do that, we are literally not taking into account the world that lies in the minds of patients, who, during the illness, are probably experiencing the fight in their bodies in a way that clearly is not strictly biological.

‘Contagion’ is a metaphor that has been employed to describe a wide variety of phenomena. So many aspects of a pandemic process are related to the way the disease is described in the population at large (as opposed to among physicians), spanning from the Plague of Athens to the fourteenth century end-of-the-world debate, and from ‘healing contagions’ and miraculous laying-on-hands to the age of viral information. We should aim to close the gap between medic and patient.

The drive for knowledge and the hope for a better future are values that, now more than ever, should guide not only the actions and studies of physicians the world over, but also the interdisciplinary contributions of philosophers and humanities.

Liliana Dell’Osso is author of Contagi, published by ETS, with a foreword by Adriana Albini