An average cancer patient in India usually seeks treatment three months after the symptoms appear. Due to lack of transport facilities and fear of contracting coronavirus, the time to seek care during the COVID-19 pandemic has doubled, with patients finally going to see a doctor six to seven months after the appearance of symptoms, affecting their prognosis.

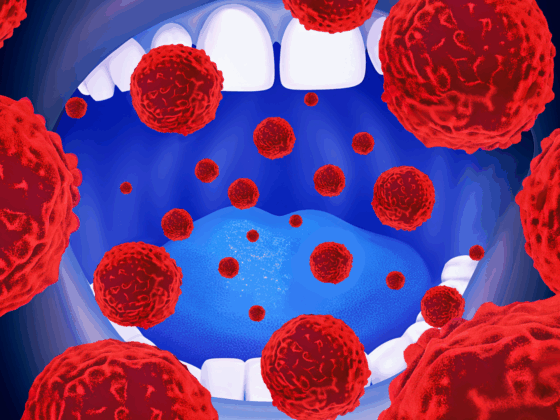

Roop Kumar is one of those who has paid the price. It took almost eight months for him to start treatment after the first appearance of symptoms. By that time Kumar, 40, had advanced oral cancer and he required eight chemotherapy sessions followed by surgery to remove part of his tongue.

Today, he sits with a tube in his mouth and his bare belongings outside the Tata Memorial Hospital, India’s leading cancer care hospital, in Mumbai. He can’t talk. His wife Somwati explains to me that this frail man was once a well-built farmer who never fell ill.

Even without the additional barriers posed by COVID, most Indian cancer patients are diagnosed in advanced stages: 68% die of their disease compared with 33% in the US. But the impact of the pandemic has been obvious ‒ the number of patients registered at the Tata Memorial Hospital dropped by more than 25%, from more than 82,500 in 2019 to less than 60,700 in 2020, according to hospital records.

But delays in diagnosis are only part of the story of the effect of COVID-19 on cancer patients in India. When India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a nationwide lockdown on 25th March 2020, it wasn’t just industrial, commercial, religious and cultural activity that came to a halt. Private hospitals, on which 70% of Indians rely for treatment, also shut down during the initial months of the pandemic.

The Health Ministry released guidelines to postpone non-emergency surgery and outpatient departments in hospitals. Cancer patients with compromised immunity were especially at risk of infection and struggled to find treatment as many hospitals turned into COVID care centres.

Around 51,000 cancer surgeries were postponed in India during the pandemic, according to an estimate published in the British Journal of Surgery.

Unlike most other public hospitals that either converted into COVID care centres or stopped non-emergency surgery and out-patient appointments, Tata Memorial Hospital decided to stay open and treat cancer patients. “We were very clear that cancer itself is an emergency. How can it wait for COVID-19?” said Shailesh Shrikhande, Deputy Director and head of the Surgical Oncology department at Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai.

Surgery continued but there were new precautions: in the early weeks, when COVID diagnostic testing was not available, patients had chest CT scans.

The team at Tata published a paper in the Annals of Surgery in June 2020 about the outcomes of elective cancer surgery conducted between March 23 and April 30, 2020. The hospital conducted 423 surgeries during that time – 371 without a COVID test and 84% surgically complex procedures. There were no deaths.

By the end of 2020, the hospital had conducted 1,362 gastric surgeries – only about 350 fewer than 2019. “Had Tata Memorial Hospital not conducted these surgeries, there is no doubt that the mortality due to cancer would be much higher,” said Shrikhande.

Girish Chinnaswamy, Professor of Paediatric Oncology at Tata, explains that the hospital had to find innovative ways of ensuring that patients who could not reach the hospital still got their periodic follow-ups. Most required a chest X-ray and blood tests, which doctors asked them to do locally, “We then examined their reports, prescribed them medication and in many cases even couriered them medications they could not find,” said Chinnaswamy.

Out-patient numbers in the now re-opened private hospitals are reaching pre-COVID levels. “Since the last few days, I am seeing patients who stayed at home during the lockdown and whose cancers have advanced, making the treatment costlier, taking longer treatment and with poor survival rates,” said Anil Heroor, Head of Surgical Oncology at Fortis Hospital, Mumbai, a private hospital chain.

One patient stayed at home for eight months with what he thought was piles, and took herbal treatment. “By the time he saw a surgeon, who referred him to me, his cancer had reached his lymph nodes and his entire rectum needed to be removed,” said Heroor.

Heroor believes that, while there has been much talk about telemedicine and its role in providing care, it can’t replace physical examination, especially during diagnosis. He recounts the case of a breast cancer patient whose scan showed a tumour of 2.5 cm, which led a doctor to discuss breast conservation. But when he physically examined her, it was clear the tumour was much bigger. The patient eventually needed a mastectomy.

However, telemedicine does have a role to play in India, reducing costs for patients who need to travel for bi-annual check-ups, “It has become a regular practice to use video calling facilities with patients who are doing routine follow-ups,” said Chinnaswamy. “This is a good fall-out of the pandemic.”