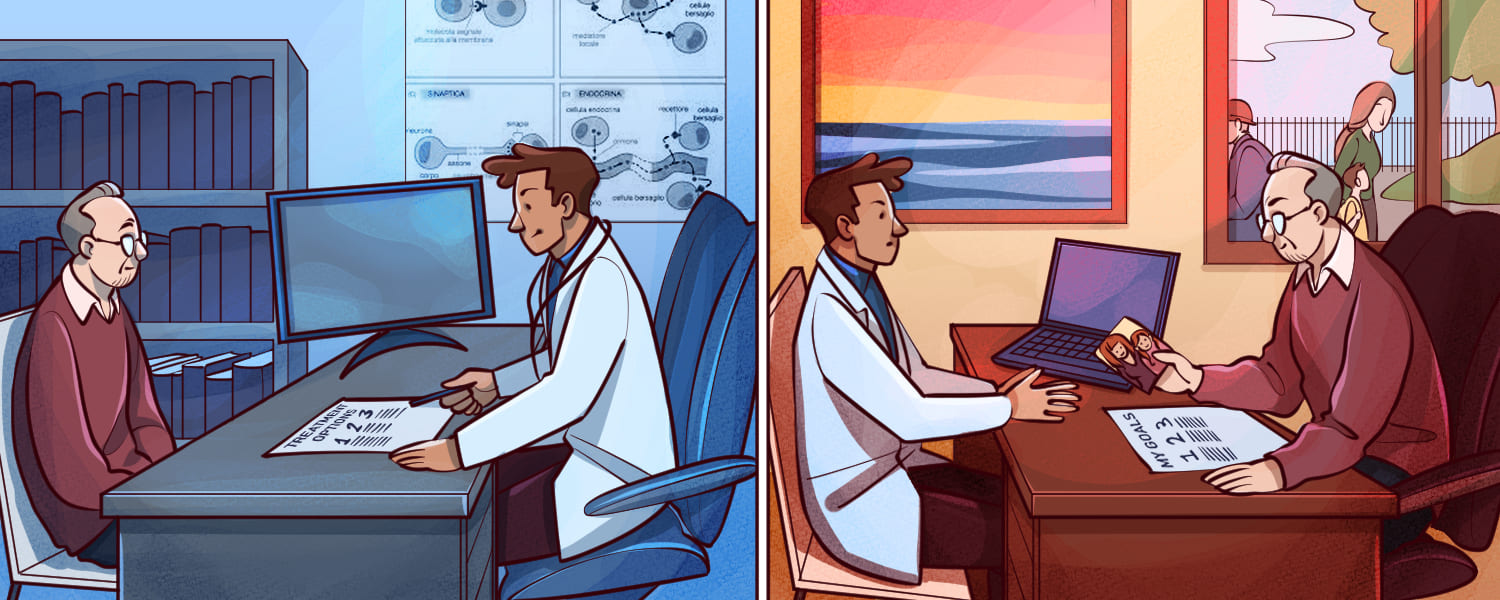

Despite growing awareness of the importance of shared decision making in cancer, there is plenty of evidence that it is still not being implemented as it should be.

A national survey of patient experience from the Danish Cancer Society found that three in four Danish cancer patients would prefer treatment decisions to be made jointly with clinicians. Yet one in three felt they were not sufficiently involved.

“Shared decision making is not about asking the patient: ‘What is the matter with you?’ It’s about asking: ‘What matters to you?’” says Stine Rauff Sondergaard from the Centre for Shared Decision Making at Lillebaelt Hospital, University Hospital of Southern Denmark. “That’s what we need to do more of. Clinicians often underestimate the strong wish from patients to be involved in the clinical decision making process.”

The lack of patient involvement in decision making – and the consequences of that – have been much highlighted in prostate cancer, where alternative treatments need to be carefully weighed because of the high risk of life-changing side effects, such as incontinence and impotence. A new quality of life study by the European prostate cancer patients’ coalition, Europa Uomo, has found that one third of patients feel that their doctors did not sufficiently help them weigh treatment decisions after diagnosis.

The consequences can be far-reaching. A study of 2,072 prostate cancer patients in JAMA Oncology is the latest addition to evidence indicating that lack of involvement and understanding can lead to long-lasting regret. Sixteen per cent of those undergoing surgery and 11% of those undergoing radiotherapy expressed treatment-related regret at five years. They came to understand the potentially severe side effects of prostatectomy or radiation therapy too late.

The study authors say the results demonstrate the importance of patient engagement in decision making.

But the consequences of not involving patients extend beyond regret. If physicians don’t regard patients as partners, they can drive decisions that are entirely out of line with a patient’s life priorities.

“More than half of the patients perceived that they had not shared the same treatment goals as their physicians”

According to Teodora Kolarova, Executive Director of the International Neuroendocrine Cancer Alliance, a patient advocacy and research organisation, physicians often assume that a cancer patient’s first priority is survival. This is not always the case. A recent US study found that only 30% of adults with advanced neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) would choose survival as their most important health outcome.

“So that busts a myth,” says Kolarova. “Clearly, patients with NETs strongly value independence over survival – the majority selected other specific treatment goals as more important, such as maintaining the ability to do daily activities, reduce or eliminate pain or symptoms. Almost 67% of those surveyed agreed with the statement: ‘I would rather live a shorter life than lose the ability to care for myself.’”

The survey seems to confirm a long-held suspicion that doctors’ focus on prolonging overall survival, even if it adversely affects other quality of life outcomes, is often out of line with patients, whose priorities are more nuanced.

“It is of huge concern that more than half of the patients perceived that they had not shared the same treatment goals as their physicians,” says Kolarova. “So what we need to do is foster an honest dialogue with patients about treatment goals, priorities, health outcomes. We need to challenge the traditional dogma that patients just want to live longer. And medical teams need to understand and respect patient preferences in order to achieve a truly personalised treatment plan.”

Current implementation of shared decision making – some facts and figures

What’s going wrong?

Why isn’t this happening? It’s not as if the issue hasn’t been publicised and promoted in the past decade. The European Code of Cancer Practice, the European Cancer Organisation’s patient-centred manifesto which goes back to 2014, includes the right to information and the right to shared decision making among its ten core requirements. The need for shared decision making is specified in health service guidance around Europe – for example, in the UK, as part of the NHS Commissioning for Quality and Innovation guidance published in 2022.

There are many potential barriers. Some come from patients themselves, as they struggle to make sense of a cancer diagnosis. Depression, anxiety, fear and educational, cultural and linguistic barriers all get in the way of them understanding information or being able to successfully engage in decision making.

Support for patients

“This means it is very important to provide counselling, therapy and support groups and other resources that make psychological function possible,” says Csaba Degi, Full Professor in Habilitation at the Babeș-Bolyai University, Faculty of Sociology and Social Work in Cluj Napoca, Romania. “Shared decision making is not something that can be accomplished without taking into account the context of the client, and where he or she is coming from.”

Inequalities – for example, in education, or access to information, and support – can create obstacles to shared decision making, says Degi. “Cancer has such an impact on our psychology,” he says. “So shared decision making is not just about information, it’s about the way we cope with information and process information and that’s something we do in the context of the family system and the provider system.”

This issue is highlighted in a new paper in the Journal of Cancer Policy, produced by the Anticancer Fund and the European School of Oncology, which stresses the importance of cancer literacy in shared decision making. It points out that the sharing of robust data-based information is often hindered by exposure to misleading information online and in the media. This negative trend also needs to be overcome, and health literacy increased across populations.

“Many patients wish to participate in decisions about their own care, but this can be influenced by the degree of health literacy which they possess and their socioeconomic status,” says lead author Guy Buyens from the Anticancer Fund. “Therefore, these areas should be considered when devising a cancer literacy strategy.”

Support for clinicians

Nicolò Matteo Luca Battisti, President of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology and Co-Chair of European Cancer Organisation Inequalities Network, agrees that inequalities get in the way of shared decision making. But this isn’t just about patient empowerment and access to information. In many hospitals there are practical constraints – such as lack of time, staffing and facilities – that make shared decision making very difficult.

“Hospitals often need support and guidance to prioritise shared decision making in specialised pathways such as oncology, says Battisti, who is Consultant Medical Oncologist at the Royal Marsden in London. “Do we really train enough healthcare professionals in the benefits and value of shared decision making, and do we provide them with an adequate skill set?”

A way forward is being highlighted by the Centre for Shared Decision Making in Denmark, which is driving and co-ordinating efforts to implement shared decision making at a clinical level throughout Southern Denmark. The centre was established in 2014 at Lillebaelt Hospital in Vejle as a research initiative to build strong collaboration between clinical, academic, and patient communities. It is a national knowledge hub for shared decision making and develops and evaluates tools to aid patient involvement.

“Do we train enough healthcare professionals in the value of shared decision making, and do we provide them with an adequate skill set?”

The centre is implementing shared decision making across all hospital units in Southern Denmark, one of five national health regions. According to Stine Rauff Sondergaard, one of the first challenges in all health settings is to dispel the widespread belief from clinicians that they are already implementing shared decision making.

“They think they are doing it already,” she says. “So did I the first time I heard of shared decision making. But once clinicians properly try the concept as we propose it in consultations, they realise they aren’t – and definitely not every time with every patient.”

Some clinicians, she says, resist shared decision making because they fear that it will result in bad decisions. “In fact, the literature shows that there is a trend towards more conservative decisions when shared decision making is used. There is no sign indicating that decisions made are more irresponsible. On the contrary, the research shows it may prevent overtreatment.”

“Another concern is that shared decision making, and using decision making aids, may be time-consuming. But in our experience, it takes a few minutes longer, no more than that.”

Implementing shared decision making across a department, the centre has found, requires systemic changes and skills upgrading, which trickle down expertise from the specialist centre level to individual clinicians. The relevant department first appoints a shared decision making team. Then, from that, the Centre for Shared Decision Making trains department leaders and teachers, who then go on to teach colleagues. Alongside this, departments need to develop or adapt tools and information, specific to cancers and local provision, that can help patients through the decision making process.

Since the programme began in 2019, 45 departments in Southern Denmark have begun implementation, with 139 clinicians trained as shared decision making teachers (16 in oncology) and 1181 clinicians trained in shared decision making by those teachers. More than 40 patient decision aids have been developed, 15 in oncology.

“Decision helpers are strong facilitators of shared decision making, but patients and clinicians need to be involved in their development”

It is an easily reproduceable model. But Stine Rauff Sondergaard says that success is largely dependent on the provision of high-quality decision aids, which can be used from the very beginnings of clinician dialogue with the patient, to help define their preferences and values. The centre has developed a generic template for a “decision helper” to help with this task, which can be adapted to the needs of each clinical area. It includes cards showing benefits and risks for each treatment option, statistics on comparative risks, and patient quotes about their experiences. Finally, the cards ask the patient whether they are ready to make their decision.

“We believe that high-quality decision helpers are strong facilitators of shared decision making,” says Stine Rauff Sondergaard. “But patients and clinicians need to be involved in their development, which should involve workshops, testing and adjustments.”

The development of effective decision helpers needs to be accompanied by more general efforts to increase cancer literacy. This has become a priority for the European Cancer Organisation, which in January 2023 published a set of recommendations to address cancer literacy issues. The organisation is calling for government funding for advocacy organisations to support cancer patients to obtain personalised information, and for the development of communication skills to be prioritised among oncology professionals.

One of the patient advocacy organisations spearheading the improvement of patient involvement on a European basis is Myeloma Patients Europe, which has launched a new research study on shared decision making in myeloma, in collaboration with Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium. Through a literature search, qualitative interviews with patients, and a survey of both patients and clinicians, it aims to gain better understanding of what shared decision making means to myeloma patients, as well as investigating what kind of patient information might help them and finding examples of current best practice.

“We are hoping that we will get a better picture of what is happening in clinical practice across Europe, what patients wish could have been done better and how we can improve that,” says Silène ten Seldam, Research Manager at Myeloma Patients Europe. “This will help develop disease-specific recommendations to improve shared decision making in myeloma.”

The research has only just begun, and actions will be dependent on its outcomes. However, one result might be the development of a validated decision making aid specific to myeloma.

“Many patients don’t really know what the concept means… many are not even aware that decisions can be made with a clinician”

According to ten Seldam, it has already become apparent that some very basic work on understanding may be required. Just as some clinicians don’t appreciate what shared decision making involves, they may also be overestimating patients’ grasp of the idea.

“From brief conversations, and from the first phase of the project, it seems that many patients don’t really know what the concept means. That’s an issue in itself. It may be because it’s called ‘shared decision making’ rather than ‘treatment decision making’ – we don’t know. But many are not even aware that decisions can be made with a clinician.”

Equally, she says, it is wrong to assume that all patients want to be involved in decision making. “It’s okay if they don’t, but the first step for any treating physician is to find out to what extent the patient wants to be involved. They shouldn’t make assumptions based on the patient’s background or education for example. We need to make sure that biases don’t come into play.”

The Europe-wide perspective of Myeloma Patients Europe – and other international cancer patient organisations which are advocating for effective shared decision making – not only provides a patient-centred perspective on which to build recommendations and good practice; it also guards against the limited national and professional perspectives that can all too easily dominate.

For example, ten Seldam points out that it is all too easy to assume that “shared decision making” applies only to choosing from a menu of treatment options. “In some countries, in eastern Europe for example, there may be very limited treatment options available, or even only one. I think it’s very important to understand that shared decision making isn’t necessarily only about treatment decisions – it can be about the whole care plan. So even in countries where there are limitations, the treating physician should still be engaging with the patient and their individual needs, because there may be a broader way of caring for that patient.”

“Shared decision making isn’t necessarily only about treatment decisions – it can be about the whole care plan”

“This might embrace pain management or psychosocial support. You can only provide that to a patient when you know what they need. Equally, even if there’s only one treatment, the mode of administration can be important to the patient. Can it be taken at home or administered in hospital? At the end of the day, it’s only the patient who knows what factors are important to them.”

Ultimately, the simple reason that shared decision making isn’t happening as widely as it should is that it needs to understood better – everyone: clinicians, patients and policy makers alike. Some of the basics still need to be done before widespread implementation can occur. Thankfully, the work of patient organisations and cancer organisations like ECO is finally putting to rest the assumption that shared decision making is simply a question of asking patients what they want. And patient advocates, academics and specialist centres are increasingly putting the tools into place for the enlightened to pick up.

This article is partly based on contributions to a virtual meeting on informed and shared decision making held by the European Cancer Organisation with the Anticancer Fund