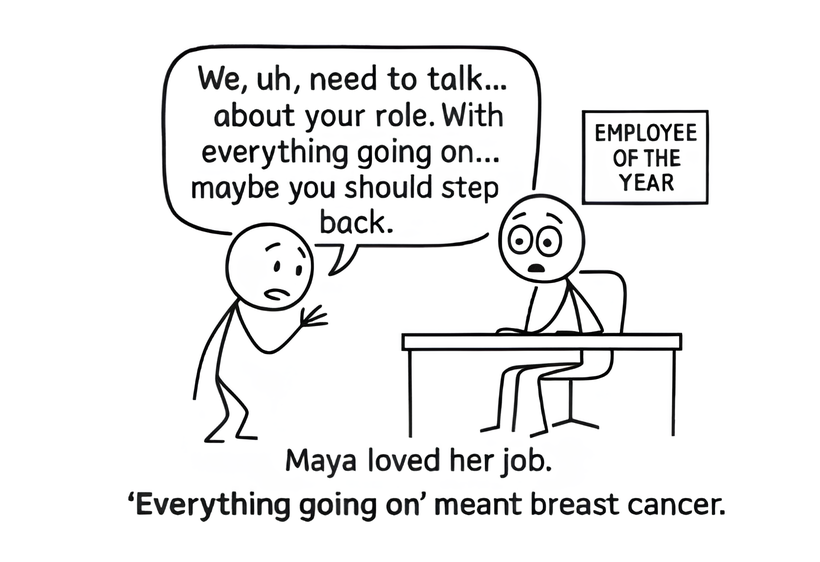

Workplace discrimination remains one of the most persistent and underrecognized challenges faced by individuals diagnosed with cancer. While advances in treatment have significantly improved survival rates and quality of life, many patients and survivors encounter a different kind of battle when returning to or remaining in the workforce.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, only 64% of survivors manage to return to work, a range from 24% to 94%, depending on cancer type, treatment side effects, and support systems.

In this article, we will discuss how cancer-related discrimination is influenced by factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, and cancer type. We will also delve into the statistics surrounding this issue, shed light on the “five-year rule”, and explore how discrimination varies across different countries and job sectors.

What is Workplace Discrimination?

Workplace discrimination refers to unfair or unequal treatment of an employee or job applicant based on characteristics such as race, gender, age, religion, disability, sexual orientation, or other protected attributes. It can occur in various aspects of employment, including hiring, promotion, pay, job assignments, training, and termination. Discrimination may be direct (explicit and intentional) or indirect (resulting from policies or practices that disproportionately disadvantage certain groups).

In his book Work and Illness: The Cancer Patient, Barofsky argues that employers often discriminate against employees with cancer to avoid interacting with individuals they perceive as part of an undesirable group—even when such actions risk financial loss through litigation and legal sanctions. On the other hand, over thirty years ago, Fobair and Hays reported that discrimination in the workplace against individuals living with cancer was often self-imposed, driven by internalized stigma, passive coping styles, and diminished self-esteem. Around the same time, Skipper argued that many employers actively discriminated against employees with cancer—denying promotions, withholding benefits, or refusing to provide reasonable accommodations. In some cases, employers even refused to hire individuals living with cancer, viewing them as a burden to productivity and company resources.

Legal Protections for Employees with Cancer

Around the world, most modern anti-discrimination laws now recognize cancer as a protected condition—either explicitly or under broader disability and equality frameworks—making it illegal for employers to treat workers less favorably because of their diagnosis or recovery.

United States and Canada

In the U.S., the data tell a mixed story. Surveys show that reports of workplace discrimination among cancer survivors have declined over the past few decades. Yet the problem persists. “About 7% of U.S. cancer survivors who were employed during or after treatment reported experiencing job discrimination due to their cancer” (Pamela N. Schultz et al., Cancer Survivors: Work-Related Issues). More recent findings suggest the figure could be significantly higher: according to the Chronic Disease Coalition, 37% of survivors said they faced unfair treatment at work after completing treatment.

A 2021 analysis by David R. Strauser, Ph.D., and colleagues at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, reviewed thousands of cancer-related complaints filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). All had been fully investigated—some validated, others dismissed for lack of evidence. “About 26.6% of the complaints from younger cancer survivors were found to have merit. For older cancer survivors, the success rate was even higher—31.4% of their claims were considered valid” (Yates, 2021, University of Illinois News Bureau). The findings reveal both progress and persistence: while many survivors find legal recourse, too many still face bias as they attempt to return to work.

In the United States, protection stems primarily from the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which classifies cancer as a disability when it substantially limits major life activities—or could, if it recurs. The ADA bars discrimination and requires employers with 15 or more workers to provide reasonable accommodations, such as flexible schedules or medical leave. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) adds another safeguard, guaranteeing job-protected leave for treatment or recovery. Many states extend these rights further, creating a patchwork of strong—if uneven—protections.

Canada’s system is similar, built on a network of federal and provincial human rights laws. The Canadian Human Rights Act and each provincial Human Rights Code prohibit discrimination based on disability, explicitly covering cancer. Employers must accommodate workers to the point of “undue hardship,” whether that means reduced workloads, remote options, or extended medical leave. These protections extend beyond treatment itself—penalizing someone for a past diagnosis is also a violation of the law.

While overt workplace bias has diminished, subtler barriers remain: missed promotions, quiet exclusion, or doubts about long-term productivity. The legal frameworks in both countries are clear, but survivors’ experiences suggest that enforcing fairness requires more than legislation—it demands a cultural shift toward empathy, flexibility, and genuine inclusion.

United Kingdom

In the UK, workplace bias remains a concern for cancer survivors. A 2018 Macmillan Cancer Support survey of 1,500 UK cancer patients found that 1 in 5 (about 20%) who returned to work after diagnosis faced discrimination at work.

This includes being passed over for promotion, denied reasonable adjustments, or even forced out. Earlier UK surveys showed higher figures – for example, in 2010–2013, up to 37% of returning workers reported some form of discrimination or unfair treatment by employers/colleagues. The improvement by 2018 suggests growing awareness and legal enforcement (under the Equality Act 2010). Under this law, any person with cancer is considered to have a disability from the point of diagnosis – even if the cancer is in remission or cured.

The main acts that protect cancer survivors or patients from discrimination are the Equality Act (applicable in England, Scotland, and Wales) and the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (in Northern Ireland), specifically protecting people with cancer in employment, job applications, and other work-related contexts. Notably, this protection is lifelong: even if a person’s cancer goes into remission or they are years beyond treatment, they remain protected from discrimination arising from their past cancer. The improvement by 2018 suggests growing awareness and legal enforcement (under the Equality Act 2010), yet a significant minority still encounter workplace discrimination.

European Union

In the European Union, discrimination on the basis of disability is prohibited under the EU Employment Equality Directive (2000/78/EC), which all member states have implemented through national legislation. While the Directive does not enumerate specific conditions, the Court of Justice of the European Union has ruled that serious illnesses may qualify as disabilities when they result in long-term impairments.

Cancer is broadly recognized across Europe as a condition that can constitute a disability, particularly when it leads to lasting limitations. Accordingly, cancer patients and survivors are generally protected under national disability discrimination laws in EU member states. As the European Cancer Organisation notes, “In some countries in Europe, protecting cancer patients and survivors from workplace discrimination has included utilization of disability discrimination legislation.”

Beyond employment, Europe has moved toward broader protection for survivors in financial and insurance contexts through the introduction of a “right to be forgotten.” This legal concept allows individuals who have completed cancer treatment to withhold their medical history when applying for life insurance or credit after a defined period.

Today, ten EU member states—France, Spain, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Italy, Cyprus, and Poland- have formally enacted national laws recognizing the “right to be forgotten” for cancer survivors. Waiting periods vary: typically five years in France and Spain, seven years in Romania, and ten years in Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Italy, and Cyprus. Ireland has also advanced legislation, with a government-approved bill expected to pass in the near term.

The European Parliament’s Plenary recently strengthened these efforts by adopting the final text of the EU Consumer Credits Directive, which, for the first time in EU law, prohibits the use of personal health data, particularly cancer-related information, when determining creditworthiness. It also prevents insurers from using oncological health data in credit-linked insurance policies once a defined post-treatment period has passed. Under the Directive, EU member states may determine the specific length of that period, but it cannot exceed 15 years. Although these measures mark significant progress, Europe’s legal landscape remains fragmented, with varying degrees of protection across countries. Nevertheless, the expansion of the “right to be forgotten” and the new EU-wide directive signal a growing consensus: cancer survivorship should not carry a lifelong penalty, whether in the workplace or in financial life.

Asia-Pacific

The treatment of cancer patients and survivors can vary greatly depending on the culture of a country. In Japan, for example, cancer survivors have faced significant workplace discrimination. A 2012 survey by Aflac revealed that 10% of cancer patients were fired due to their diagnosis, while about 30% experienced salary cuts or demotions after disclosing their condition.

Some companies even explicitly rejected job applicants with a history of cancer, highlighting the strong stigma surrounding the illness.

Later on, a 2016 revision of the Basic Plan for Cancer Control urged employers to “strive” to help survivors balance work and treatment. Unfortunately, Japan has not ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, so therefore, employers may dismiss chronically ill workers under Article 14 of the Labor Standards Act for “non-performance”.

According to Sungkeun Shim et al, 24.0% of South Korean survivors (included as an analog in Asia) lost their jobs after cancer, with 20.7% citing workplace discrimination – underscoring a broader Asian context of survivor job loss.

Across the Asia-Pacific, fear of discrimination is very high. In a 2017 multinational survey, 37% of employees worldwide expressed concern about workplace discrimination against people with cancer – but in Asia-Pacific, that figure climbed to 49%.

This suggests that nearly half of the respondents in that region anticipated or feared bias against cancer-affected coworkers. Actual reported experiences in many Asia-Pacific countries are not well quantified, but anecdotal reports (e.g., in India and China) echo themes of job loss, forced early retirement, or demotion after a cancer diagnosis, indicating that discrimination is a widespread issue in the region (even if exact percentages are unknown).

Before recent legal changes, it was common for Japanese companies to explicitly reject job applicants with a cancer history or even terminate employees upon diagnosis.

“Thirty percent of cancer patients reported that their salary was reduced by up to 70% after their diagnosis, effectively pressuring them out of the workforce.”

— Triage Cancer’s 2015 survey, Cancer & Employment: International Series – Japan

Latin America

Emerging data from Latin America indicate that workplace discrimination against cancer survivors remains a significant concern. In a prospective study conducted in Brazil, about 10.7% of women with breast cancer reported experiencing employer discrimination, including unfair treatment or a lack of reasonable accommodation, within two years of diagnosis.

Among the 67 women who were working 24 months after diagnosis, 11.9% reduced their workload from full-time to part-time, while 3% increased their workload from part-time to full-time. Although many participants reported receiving some level of employer support, only approximately 29% were offered formal work adjustments. Those who did not receive such support often described feeling penalized for their illness.

This study underscores that while most breast cancer survivors in Brazil eventually return to work, a significant minority continue to experience discrimination and reduced opportunities following treatment.

Comprehensive statistics from other Latin American countries remain limited, but available evidence suggests similar patterns across middle-income nations. Cancer survivors are often pressured to leave their jobs or face barriers to re-employment due to persistent misconceptions about their health and productivity. Patient advocacy groups in Mexico and Argentina have reported numerous cases of survivors being pushed out of the workforce following treatment, although formal prevalence data are scarce. According to Luciana C. G. Landeiro et al. (2018) in Return to Work After Breast Cancer Diagnosis, the Brazilian findings likely reflect a broader regional trend, with an estimated 10–15% of cancer survivors in Latin America experiencing workplace bias, a figure that underscores the need for more systematic research and policy attention across the region.

Africa

Reliable data from African nations remains limited, but available evidence suggests that workplace discrimination against cancer patients is a significant and underreported problem. In South Africa, for instance, Maimela C. et al. (2021) observed that many employees with cancer face unfair treatment in the workplace — “not because they are unable to work, but merely because they have cancer.”

Survivors have reported being denied reasonable accommodations or even dismissed once their employer learns of the diagnosis, although precise prevalence data are lacking. The absence of continent-wide surveys makes it difficult to quantify the scale of the issue, but persistent stigma and limited employer awareness likely contribute to widespread discrimination. According to Bradshaw D. et al. (2009) in The Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases in South Africa, an estimated one in four South Africans is living with cancer, a striking figure that reflects the disease’s reach across both younger and older populations. This high prevalence, combined with already elevated unemployment levels, particularly among youth — which the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) reports at 47.5% — underscores the compounded social and economic impact of cancer-related stigma in the region.

Middle East

Cultural stigma in parts of the Middle East often leads to underreporting of workplace discrimination, as many patients choose to conceal their illness. According to Badihian, Shervin et al., 48.4% of patients said they would not inform their coworkers if they had cancer, specifically to avoid potential workplace discrimination or “problems at work.” This finding suggests that nearly half of patients fear negative repercussions in their professional lives.

Although documented cases of explicit discrimination—such as termination or demotion—are rarely publicized, the prevalence of non-disclosure points to a significant, largely hidden problem.

Gulf Region and Beyond

Across much of the Middle East, formal research on workplace outcomes for cancer survivors remains scarce. Nonetheless, awareness of the issue is growing. In the Gulf states, including the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, recent labor law reforms have explicitly prohibited the dismissal of employees undergoing medical treatment for cancer.

Despite these advances, anecdotal reports indicate that survivors may still face subtle forms of bias—such as pressure to resign, exclusion from promotions, or reduced career opportunities due to health-related misconceptions. While no precise prevalence data are available, the prevailing climate of non-disclosure suggests that many survivors continue to anticipate or experience workplace discrimination, highlighting the urgent need for stronger legal protections and cultural change across the region.

Workplace discrimination remains a significant and often overlooked challenge for individuals affected by cancer. While advances in medicine have transformed cancer from a terminal diagnosis into a manageable condition for many, survivors still face substantial barriers when it comes to employment. As we’ve seen across various global regions, experiences vary widely based on legal protections, cultural attitudes, and the presence (or absence) of supportive workplace practices.

A clear understanding of one’s legal rights, the pursuit of appropriate workplace accommodations, and open communication with healthcare providers and employers are essential to navigating employment after a cancer diagnosis. Empowered and informed survivors—alongside proactive advocacy—remain central to advancing equitable treatment, strengthening legislative frameworks, and fostering truly inclusive workplaces. Although the path toward eliminating workplace discrimination is complex, sustained awareness, education, and rigorous enforcement of legal protections continue to move society closer to a future in which a cancer diagnosis no longer endangers a person’s livelihood or dignity.

Cancer Discrimination Court Cases

Court cases from around the world reveal how legal systems respond when workers are dismissed, misled, or denied reasonable accommodations due to their illness. These cases highlight the ongoing struggle for equal rights and protection for cancer patients in employment.

United Kingdom: Wainwright v. Cennox Plc (2025)

In the 2025 UK case Wainwright v. Cennox Plc, a manager on sick leave for breast cancer treatment discovered her role had been permanently filled without her knowledge, and the employer misled her about it. A tribunal later ruled this amounted to discriminatory constructive dismissal, awarding her £1.2 million in damages.

USA, Blythe Asher v. NBCUniversal/E! (2016)

In Blythe Asher v. NBCUniversal/E! (2016), Blythe Asher—a senior executive at E! News—filed a lawsuit alleging she was fired during breast cancer treatment due to her “sickly appearance.” She claimed disability discrimination, retaliation, and wrongful termination in violation of California law. The case, filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court, drew media attention for highlighting workplace bias against high-level employees with cancer.

Africa (South Africa): Matinketsa v. Dis-Chem (2024)

In the 2024 South African case Matinketsa v. Dis-Chem, Refilwe Matinketsa, a warehouse worker and bowel cancer survivor, was dismissed after she could no longer perform heavy lifting due to lasting impairments. Though temporarily reassigned to light duties, no permanent position was available. She challenged the dismissal as discrimination, but the CCMA found it justified. The employer had explored accommodations and followed proper procedures. The termination was deemed lawful, showing that dismissal may be permitted if a cancer survivor cannot fulfil core job duties despite reasonable adjustments.

Middle East (Israel): Oren-Blazer v. Teva Pharmaceuticals (2013)

In the 2013 Israeli case Oren-Blazer v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Ilana Oren-Blazer was dismissed shortly after being diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor. The court found the termination discriminatory, awarding her estate $600,000 and setting a key precedent against cancer-based dismissal in the region.

FAQs

1. Can my employer fire me because I have cancer?

In many countries, no. Cancer is legally recognized as a disability or serious health condition, and most labor laws prohibit discrimination based on health status. You cannot be legally fired just because of your diagnosis. However, laws vary—check your local labor or disability protection laws.

2. Do I have to tell my employer I have cancer?

No, unless you are requesting workplace accommodations or taking medical leave. Disclosure is your choice. However, without disclosing your diagnosis, your employer may not be legally obligated to provide certain support.

3. What are “reasonable accommodations” and how do I request them?

These are changes or adjustments to help you perform your job during or after treatment (e.g., flexible hours, remote work, longer breaks). Write a formal request (email is fine), mention that it’s related to a medical condition, and if needed, include a note from your doctor. Keep a copy of all communication.

4. I feel I’m being treated unfairly. What should I do first?

Start by documenting everything—dates, names, what was said/done. If you feel safe, speak to HR or your manager. Use calm, factual language.

If internal steps don’t work, consult a legal advisor or reach out to a government agency or NGO.

5. Who can I contact for legal help?

- United States: Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), Cancer Legal Resource CenterUnited Kingdom: ACAS, Citizens Advice

- Australia: Fair Work Commission, Human Rights Commission

- Other Countries: Look for disability rights groups, local cancer NGOs, labor unions, or legal aid services.

6. What if I’m demoted, excluded from meetings, or bullied after disclosing my diagnosis?

This may count as harassment or indirect discrimination. Document it. Talk to HR or a manager if possible. If nothing changes, file a complaint with the relevant authority in your country or speak to a lawyer.

7. Can I take time off work for treatment?

Yes. Most countries have laws allowing medical leave, especially for serious illness. Whether it’s paid or unpaid varies, but your job may be protected during treatment. Provide a medical certificate if required.

8. What if I live in a country with weak legal protections?

Check if your country has ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Contact international labor organizations or NGOs, and connect with cancer patient groups for advice and advocacy help. In many places, awareness is growing, and informal support networks exist.

9. How do I cope emotionally with discrimination at work?

It’s completely valid to feel stressed, hurt, or isolated. Reach out to:

- Oncology social workers

- Mental health counselors

- Cancer support groups (online or local)

- Friends, family, or spiritual communities

You’re not alone—and your dignity matters just as much as your health.

10. What if I just want to change jobs instead of fighting it?

That’s also valid. Sometimes the healthiest option is a fresh start. But even then, consider speaking with a lawyer or agency so that your previous employer is held accountable—this can help prevent future discrimination for others.