“Yes,” she said. “I was named Judy after St. Jude.”

When she was old enough to learn who St. Jude was, she remembers the moment it landed with a child’s blunt logic.

“When I became old enough and learned about the saints and that St. Jude was helper of the hopeless, I said to my parents… What, you named me for some… hope? Was there a problem that you named me after the patron saint of hopeless cases?”

But the truth was simpler and deeper.

“The reality is that both my parents were devotees of St. Jude,” she said. “They both loved St. Jude.”

Her mother’s devotion came from a family story that never left them. Judy’s Aunt Laurice, her mother’s sister, had what sounded like leukemia or a blood disease, at a time when diagnoses were vague and outcomes were brutally clear.

“Her prospects were dismal,” Judy said. “My mother… found St. Jude and prayed to St. Jude, and her sister recovered.”

“Doctors said that she would never have a full life and children,” Judy recalled. “And yet she went on to get married and have four children and live… into her 90s.”

“That’s why I was named after St. Jude!”

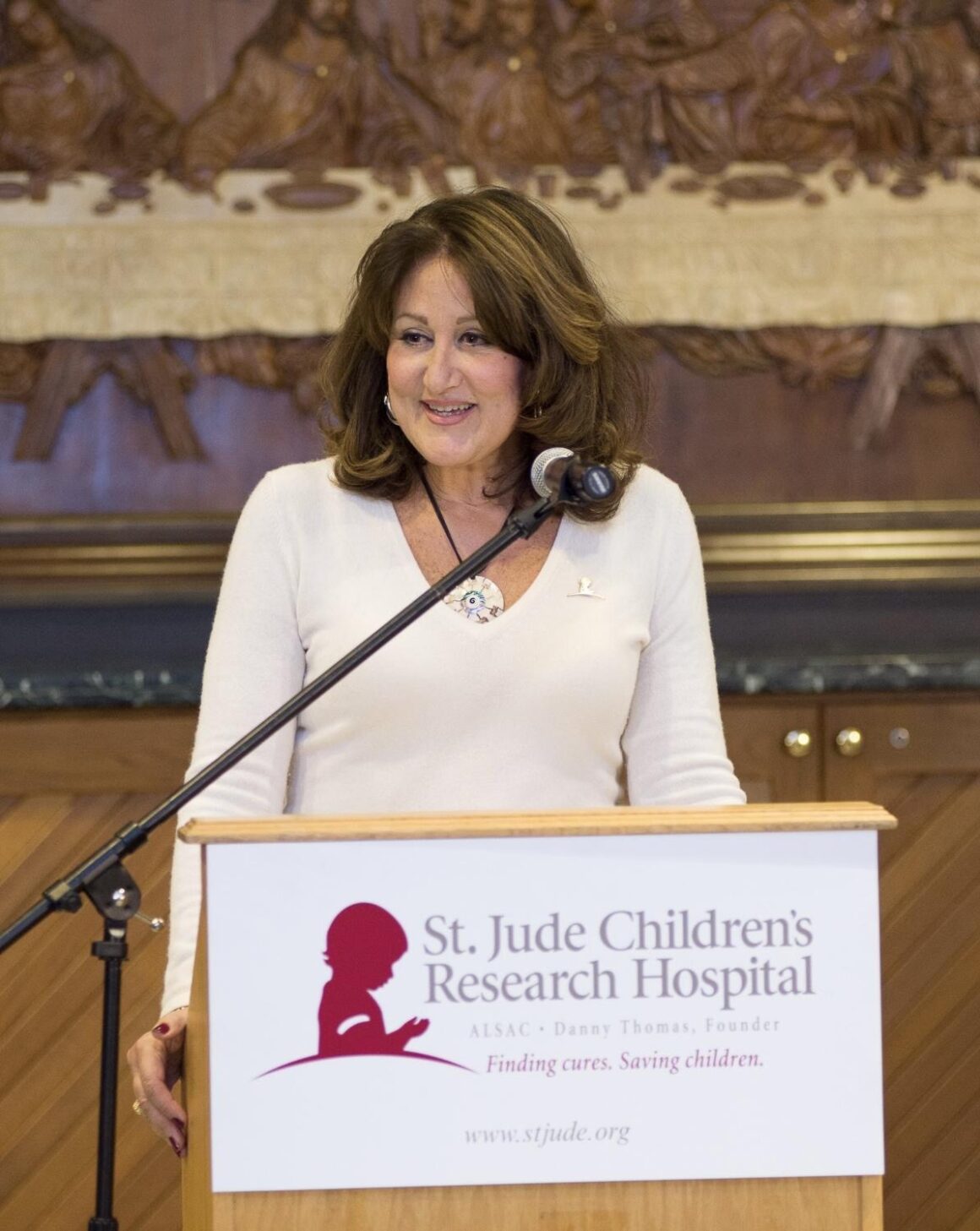

Currently, Judy Habib is serving her third year as Chairperson of the Board of Governors of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. In 2019-2021, she chaired the Board of Directors for ALSAC, American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities, the world’s largest pediatric cancer charity, today raising around 3 billion dollars a year for St. Jude.

Danny Thomas and How it All Started

Her father’s connection to St. Jude went much further back, to the earliest days of Danny Thomas’ vision.

“My father was one of the early disciples of Danny Thomas.”

Judy retold the story as something more than history; she described it as a blueprint of how movements start: promise, integrity, and a vision big enough to attract the right people.

Danny Thomas, she explained, had made a vow: he would build a shrine for St. Jude if St. Jude “would show him his way in life.” As his success grew, his promise expanded too. He didn’t just want to build a shrine; he wanted to build something that would change the fate of children.

“He had always been painfully aware of the inequity of healthcare for children,” Judy said. “If they were not of means… poor, black… end of the line, back of the room, not getting treated.”

Children were dying of things they didn’t have to die from.

So, Danny went to Cardinal Stritch in Chicago and said he wanted more than a shrine, he wanted a clinic for children, “regardless of their means… their color… their anything. All children should have healthcare.”

Cardinal Stritch had a Memphis connection, she noted, and introduced Danny to John Berry, “an amazing businessman,” who then brought in Dr. Lemuel Diggs.

And it was Diggs who changed the architecture of the dream.

“Dr. Lemuel Diggs said, ‘Danny, instead of a clinic, why not build a research hospital and find the cures for these catastrophic diseases… like sickle cell anemia, and leukemia…’”

Danny’s response was almost disarmingly simple.

“And Danny was like, ‘Okay, sounds like a good idea—so now what?’”

“No Child Should Die in The Dawn of Life”

At this point, Judy leaned into what she called the “magic” of it all, not magic as mysticism, but magic as execution: a promise honored, a vision held, and an openness that lets the right people shape the “how.”

“As I think about magic,” she said, “the purity of someone making a promise, having the integrity to fulfill the promise… having a vision for something possible… being open to what comes, and trusting that the right people come at the right time…”

She described how momentum forms: one person contributes an idea, another adds infrastructure, another adds expertise. And the leader, if the leader is real, has the ability to listen and adjust without losing the purpose.

“He had the ability to say, “Okay, I hear what you’re saying, that makes sense, say more.’”

And at the center of it, a statement that is less a slogan than a moral position:

“That no child should die in the dawn of life.”

ALSAC: “Saying Thank You to America.”

Vision needed money. And early on, Judy said, Danny tried what many founders try first: his immediate circle.

“He had a couple of dinners with his celebrity friends, and raised… 100, 200 thousand dollars,” she said.

Then reality hit.

“After a couple of years, he said, ‘This is not sustainable… maybe we need to have the nuns take it over, because they know how to build and run hospitals. I don’t.’”

That’s when a friend, Mike Tamer, offered an idea that was part fundraising strategy, part community identity.

“Our people are new to this country,” Judy quoted him. “People don’t know Aboussie, Haddad, Hajar, Habib… they know Smith, Jones, Reilly…”

And then the line that became a purpose statement:

“This would be… our way of saying thank you to America.”

Danny liked it.

So instead of flying— because the movie studios felt it was too risky at the time—Danny and his wife, and Mike Tamer, got into a station wagon and drove from Beverly Hills to Boston, “and everyplace in between,” collecting what Judy called “his disciples.”

Then Danny did something Judy still talks about as a leadership case study.

“He disseminated leadership,” she said.

He would go city by city—Cleveland, Chicago—and effectively say: you’re in charge.

“I don’t care how you do it,” he would say. “We gotta raise money.”

And then, in a sentence that captures both the bluntness and the urgency of building something impossible:

“Have your chicken dinner, have your golf outing—stand on your head and spit nickels—I don’t care. Raise money. Figure it out. But you’re in charge.”

Judy paused and then added something important: this wasn’t just a mechanism. It created pride. It created belonging. It created speed. It was 1957, and ALSAC was born.

“There are certain things that he just did by gut instinct,” she said, “but I look back and say this should be a case study in the Harvard Business School.”

Two Organizations, One Mission

Judy grew up with St. Jude as a family reality, not a distant institution.

“I was very young when my father would go to board meetings,” she said, “but every year we would go to these ALSAC conventions.”

ALSAC, American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities, was created with one clear purpose: raise funds and awareness for St. Jude.

And Judy emphasized a structural decision that mattered: ALSAC and St. Jude were distinct, but interdependent.

“He created these two organizations… but the same people served on both boards.

“All ALSAC worried about was raising money and awareness,” she said. “And St. Jude was about… finding cures and saving children.”

At those conventions, she watched an early version of institutional learning in real time: cities sharing “best practices,” what worked, what failed. Doctors updating the community: what they were studying, how cure rates were improving, what equipment or buildings were needed next.

And one constant refrain:

“We have to raise more money… we have to raise more money…”

But there was never a question of whether St. Jude would get what it needed.

“Danny would say, ‘Whatever they need, ALSAC is going to get it for them—we’ll just figure it out.’”

A Young Woman, Nursing, and The Moment Reality Disagreed

Judy’s own career path started in the world her generation was offered.

“At the time that I was growing up, little girls grew up and they were teachers, nurses, and secretaries.”

Her father was the first in his family to go to college. He wanted to be a doctor. He became an obstetrician-gynecologist. She thought: I’ll be a nurse.

“I’m going to go to Boston College, then the best nursing school in the country,” she said, “and we’ll all live happily ever after.”

Judy took summer jobs as a nurse’s aide.

“I loved being a nurse’s aide, I loved the interpersonal contact with patients.”

But once she was in college and started clinical rotations, her perspective changed. The system didn’t match the ideal.

“The healthcare system was not what I had imagined it to be. Not… the integrated healthcare team, centered around the patient… It just wasn’t like that in the real world.”

And she saw something else: undervaluation.

“I felt that nurses were really undervalued, perceptually and financially,” she said.

So, she made a decision that many people feel but few name so directly:

“I really felt like I was either going to need to transform the nursing profession or come up with plan B.”

Business, Storytelling, and “The Gift of Not Knowing”

Plan B became business.

She made an appointment with the Dean of the School of Management at Boston College, and even that entry started with persuasion.

The dean challenged her: “Why would a nice girl like you want to leave nursing?

“After a couple of hours,” Judy said, “he said, ‘Alright… you’ve sold me on this… I guess you can sell anybody anything.’”

Her first job was in sales for Scientific Products, a division of American Hospital Supply, supplying research laboratories.

“The irony,” she said, “was that when I was in nursing school, I did not love labs. And my very first job was spending all my time calling on laboratories.”

After five years of record-breaking sales achievement (and the first woman in the industry), she left to test her entrepreneurial wings with a start-up. Although it was a great experience, she knew it was time to go corporate. She landed a role in strategic planning and loved it. But after a couple of years, the head of sales and marketing asked to lead marketing communications.

Judy asked him, “I love what I’m doing now. Why do you want me to take over marketing communications?”

The answer was practical.

“Because you understand strategy, you understand sales… we have 200 salespeople, and they need better support… I trust you… and you need the management experience.” It turned out to be a great move, she worked with world-class agencies, and the company reached new heights of recognition.

But after five or six years, she reached a breaking point many high performers recognize.

“I was tired of the bureaucracy of corporations, tired of politics.”

She knew what she actually loved:

“What I loved was… helping people and organizations see and realize what’s possible.”

And she realized that the lever for that is language.

“I realized the importance of telling a good story. And that it’s all about communication.”

So, she left the safety of the corporate world and launched what others might call an ad agency, but she refused the label.

“I called this company like the Uncola of advertising agencies,” she said, “because it wasn’t just about advertising.”

It was about helping organizations “understand and tell their own story” so, people would want to join, buy, support, commit.

“It all begins with ‘how are you telling your story?’”

Her firm, Kelly Habib John (KHJ), was built with commitment more than certainty.

“We had no roadmap for what we were taking on,” she said, “but we were just really committed…”

Then she said something that reveals her as both builder and believer:

“The greatest gift is the gift of not knowing,” she said. “I never worked in an agency, and I started one.”

“But God gave me a good brain,” she added, “and a really high empathy listening for what there is to do… what there is to see… what there is to hear… and then what there is to say.”

They “figured it out,” built a strong independent firm, employed many people, and told “some really good stories… for wonderful companies” over three-plus decades.

Bringing Her “Adult Professional Self” to St. Jude: Reputation vs Brand

St. Jude was always part of her life. But she reached a point where she asked: how can I contribute more?

She joined the marketing committee. Within a year, she was asked to join the board.

And when she arrived with professional eyes, she saw something powerful yet incomplete.

“What I saw was an organization that was doing amazing things, and… it had a great reputation.”

But the communications were fragmented.

“There was the St. Jude logo. It was in red, blue, green, different shapes and sizes, type fonts, and lots of pretty colorful flyers.”

“It was functional, but all over the place,” she said.

So, she made a presentation to the board and leadership about a distinction she clearly believes every mission-driven organization must understand:

“You need to understand the difference between reputation and brand.”

“Reputation is what people experience of you,” she said. “We have a wonderful reputation because… families… come in with a sick child and go home with a child that’s going to be okay.”

Fundraisers felt proud; donors felt meaning; outcomes were real. Reputation was deserved.

But the brand was now their responsibility.

“Our founder… isn’t going to be here forever,” she said. “We need to pay attention to something called a brand.”

And she defined brand in a way that is both simple and strategic:

“Brand is how you are being responsible for how people think and feel when they see or hear your name.”

It’s “being very deliberate” about how you look, how you speak, organized with consistency so reputation becomes momentum.

“You’re putting an engine to it,” she said, “so that you can accelerate the momentum.”

Her company KHJ did pro bono work for St. Jude, refining its logo “so that it could always look the same way,” while keeping “the essence of the original.”

And she pointed to two lasting outcomes she’s proud of: the consistent logomark “with the beautiful child” that “is what you see today.”, and the positioning line that became a global signature:

“Finding cures. Saving children.”

She smiled and paused.

Judy Habib: Both/And

When Judy Habib speaks about St. Jude, she doesn’t speak like a board chair describing governance. She speaks like someone who grew up watching a living organism, built on story, tension, pride, and purpose, learn how to scale without losing its soul.

As a child, she would attend the ALSAC conventions with her parents. And there was one privilege that shaped her early understanding of leadership: families were allowed to sit at the edges of the boardroom.

“We’d be in a hotel… a big ballroom,” she said. “The board members were all at a table and we got to sit on the outside and watch the boardroom.

It was so amazing to see these mostly men… many of them of Middle Eastern heritage… arguing about how something was going to go forward and how we were going to allocate the budget.”

And the arguments, she said, were not about ego. They were about mission, about where the money should go.

“No, there should be this much money for research.”

“No, you should put this much money more to treatment.”

“No, it should be this program… to find the next cure.”

“No, it should be this because we have to make sure that the patients…”

“It was always this sort of battle and tension,” she said. “Research, clinical, research, clinical.”

Even back then, everyone knew the secret of St. Jude: “the magic… is the bench to bedside translation.” But inside the boardroom, the question kept returning in different forms: Is it this? Is it that?

That tension is what gave birth to one of the most recognizable brands in global healthcare.

“When we were thinking about the brand,” Judy said, “I said, you know what? It’s not either/or.”

“The essence and beauty of the place is that it is both/and—and it shall always be both/and.”

And then she said the sentence that, in her mind, holds the identity of the institution:

“Because who we are and what we are about is finding cures and saving children.”

“Let us always remember that it’s a both/and—finding cures, saving children,” she said.

She smiled when she described what happened over time.

“I’m very pleased to say today… the public recognizes just that tag-line. Seventy-five percent of the public says, ‘Oh yeah, finding cures, saving children. That’s St. Jude.’ It’s very thrilling.”

“And it remains so to this day,” she added. “It really is who we are and how we speak.”

“There’s Only One Beginning to Something Great”

“Hearing the founders speak about the early days was so precious,” she remembers. “It was like a little kid sitting at the knee of their grandparents… hearing stories that were just so precious.”

Then she recognized a leadership risk that many organizations ignore until it’s too late:

“These stories could not disappear. We could not let these stories go away with our founders going away.”

Because, she said, a great brand isn’t only a logo or a slogan.

“It has an essence. It has a soul.”

She compared it to something timeless: the way Native American storytelling carries meaning across generations.

“They tell stories and the stories go from generation to generation.”

So, she built an archive, not with documents, but with a film.

She called a producer friend, Peter Ryan, and asked him to volunteer his talent.

“I want us to create a film… capturing the stories of this founding generation, because they are precious.”

“And there’s only one beginning to something great,” she added. “You never want to lose the story of the beginning.”

They interviewed 25 of the earliest “disciples” and created a 35-minute film called The Dream, a portrait of immigrant identity, gratitude, community, and national mobilization behind Danny Thomas.

“It really does tell the story of what it was like to be new immigrants to America… what it was like to come together nationally and get behind their hero… and create this great St. Jude.”

She described specific voices she still hears from the film:

“Emil Reggie from New Orleans… ‘Roots, roots. You can never forget your roots… If you don’t have roots, you’re nobody.’”

And Peter Decker, “the singing attorney from Virginia,” speaking about Lebanese people and their “purity of heart.”

“These were not people of wealth,” Judy emphasized. “They were doing it because they were so present to the gift it was to be in a place where they could see and realize possibilities for their families.”

“They wanted to give back,” she said. “And St. Jude was the way.”

She believes the film should be institutionalized.

“It’s something that I believe probably could and should be shown to every employee… so that you just never let it be forgotten how it began.”

Sophistication Without Losing Heritage

Decades serving on the board gave Judy a front-row view of two evolutions happening in parallel: St. Jude and ALSAC growing larger, more complex, and more professional, and the board needing to keep up.

“We started looking at ourselves and saying, we need to grow in sophistication to ensure that we are properly governing these two organizations,” she said.

“But we can never lose our heritage.”

Here Judy credited Marlo Thomas as a guardian of the founding identity.

“Marlo Thomas was probably the biggest advocate of ensuring that that would never happen,” Judy said – so much so that Marlo supported a bylaw requiring a significant percentage of the board to remain Lebanese-Syrian in heritage.

“We will never lose the ALSAC/St. Jude connection, and our heritage should always be a point of pride… because one of her father’s intentions was that this would be our way of giving back.”

But that principle didn’t mean staying small or insular. So, they have been “pruning and curating,” evolving board composition to bring in expertise, people who can ask the second, third and fourth questions when management brings proposals for consideration.

“We are committed to have the full sophistication and experience of a world-class board to govern these world-class organizations.”

The Challenge that Never Goes Away

When I asked Judy what has been most challenging throughout the decades, she went right back to the original boardroom energy she watched as a child.

“The challenge today… is no different from what the challenge was on day one,” she said.

“Competing passions for what’s next and how it should be.”

That passion looms large in both St. Jude and ALSAC, and also inside the boardroom itself.

“There’s such a voracious appetite for so much to occur.”

Board size was part of the complexity. Today it’s 31.

“At one time… in the early days, the board was as large as 55 people. Which is crazy. But it was a different time.”

Still, she’s clear on the practical logic: two distinct organizations, “two different businesses,” with heavy governance load.

Their “sweet spot,” she said, is “25 to 35.”

And her job as Chair is not to eliminate passion, but to steward it.

“Managing the dynamic of all of those competing passions… that’s what there is to do. So that people can leave the room at the end of the day and still want to breaking bread together, as they did in the early days.”

“Knowing Nothing and Bringing Everything”

When I asked what was key to her success, how a young woman who once planned to become a nurse became chair of the board of one of the world’s most consequential pediatric cancer institutions, she answered with the same humility that runs through her whole story.

“Knowing nothing and bringing everything,” she said.

“Listening really well and learning really fast.”

She traced it back to KHJ, the company she built and led for 35 years.

“Helping people and organizations see and realize what’s possible for themselves and the world around them.”

Over three decades, she worked across Fortune 100 companies and startups, healthcare and biotech, finance and economic development, becoming, as she put it, a “student” of what works, what fails, what makes great leadership and culture.

And she returned to a line she had used earlier, one of her core beliefs:

“The greatest gift is the gift of not assuming that you already know.”

“Sometimes I think that an attitude of ‘I know’ gets in the way of really astute listening and a kind of curiosity that can bring true understanding,” she said.

She described her board work as “a labor of love.” It’s volunteer service, but deeply personal service.

And right now, the timing matters.

“I do feel a confidence that I am the right person at the right time for this board, because we are at a moment where we are passing the torch from our founders to our future.”

And there’s urgency in her voice when she explains why.

“We are the last people that got a hug from Danny Thomas… When we’re gone, that’s it.”

So, the responsibility isn’t only operational. It’s cultural.

“How are we setting tracks for the future… culturally… how do we ensure that we always have that purity of purpose and passion for performance?”

“That can never go away,” she said. “Because that is the secret of our success.”

“A Big Mountain to Climb”

Judy then widened the lens into a pattern she’s observed across businesses as they mature: the founding generation is fueled by passion, second-generation is challenged to build on that foundation; the danger that faces the third generation is when success becomes comfortable.

“Complacence is the biggest killer to business,” she said. “Complacency is a killer… you get comfortable… values can wane, and there are cracks in the foundation.”

She explained how the second generation initially felt when taking the helm from the founders:

“We were scared. We’re like, ‘Holy God, it’s up to us…’”

“Our number one job: just don’t mess it up.”

But they didn’t just hold the line, they built.

“We were raising… five, six hundred million dollars a year,” she said. “And today… we’re probably hitting three billion a year.”

“That’s pretty amazing,” she added, because it means millions of people are “enrolled in our story.”

Then Judy pointed to a turning point in global ambition, when CEO Jim Downing pushed the institution beyond its success in America toward a more sobering global reality.

“Danny didn’t say no child should die in the dawn of life in America. He said no child should die at the dawn of life.”

The moral question that has become strategy and part mantra in the boardroom:

“If not St. Jude, who? If not now, when?”

And she described the beginning of what followed: Dr. Downing’s commitment to recruit the best person to lead this next chapter of the St. Jude story – Carlos Rodriguez-Galindo.

At the St. Jude Global Convening she had just attended, Judy said she felt something familiar: the entrepreneurial spirit of the earliest ALSAC conventions.

“A big mountain to climb,” she said. “We don’t know exactly how… but we all care about the same thing.”

“Let’s share successes, share failures… connect the dots… come together… and get it to happen.”

And she underlined what she believes is a defining St. Jude trait:

“There’s never a complacence that it’s done… There’s always a humility… there’s just so much more to do… and let’s do it.”

“In The World of Good and Evil, in The World of Light and Dark, St. Jude is Good, and St. Jude is Light.”

When I asked what she envisions 10, 20, 30 years from now for St. Jude Global, she corrected the framing gently.

“When you say St. Jude Global, it’s as if it’s a program… But what I see is that St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital is a global entity…”

She highlighted foundational science as the first pillar, especially at a time when government investment is not “as generous as one might hope.”

“Discoveries begin there, and then it’s built upon by everyone everywhere… no authorship on the discovery.”

Touching on one of Danny Thomas’s founding principles:

“We’ll share our knowledge as soon as we get it.”

Then she stopped herself when she almost used the word “leader.”

“We’re not about being the singular leader in anything,” she said. “That has so much ego to it.”

But she did describe what she believes St. Jude models: convening people with pure intention, openness, and a desire to collaborate for the greater good.

“A model for what it looks like to contribute in a world that is really humane.”

And then she offered a moral statement, not a corporate one:

“In the world of good and evil, in the world of light and dark, St. Jude is good, and St. Jude is light.”

Beyond science, Judy believes St. Jude generates another kind of knowledge: the knowledge of how to collaborate.

“How do you convene independent forces for a common good?” she asked. “And… share our knowledge in how to do that… because it can be applied in every way, everywhere.”

The Fifth Canvas, “Sawubona,” and The Gift of Being Gotten

When I asked about books that shaped her, she surprised me by answering with a book she is working on but hasn’t yet published.

“The book will be called The Fifth Canvas.”

Life, she explained, unfolds in “a series of canvases”, stages that complete and open into the next. She began thinking this way while her best friend was dying of multiple myeloma.

She described the canvases as themes of a life: “The Road Less Traveled,” “Relationship as sacred path,” “Community,” “Contribution,” and then what she assumed would be the last canvas: “Completion.”

But writing brought her to an unexpected punchline:

“If only we could get that we are really complete from our first breath as human beings… perfectly in-complete, always.”

Then she named one book she used constantly as a CEO: The Four Agreements.

She described a ritual: reading a short excerpt with every new employee, not as management theater, but as a way of seeing.

“I wanted them to have that experience with me,” she said.

And she used a word she loves:

“Sawubona… Zulu… it means, ‘I see you.’ Not just… I’m looking… I see your soul…”

She would ask new hires to tell their story, then listen for the first moment they deviated from the “flow” of what life had already “agreed” for them.

That earliest divergence, she said, is the moment of individuation— “if you want to get kind of Jungian about it.”

As they spoke, she would write down words, looking for the two that captured the essence of who they were. When she found them, people often cried.

“They would feel like they had just been seen… their story had been heard…”

“The greatest gift that one can be given,” she said, “is the gift of being gotten.”

Those two words became each employee’s “BE words”—who they are being in the world—printed on the back of their business card, and even on personalized coffee mugs.

Clients noticed. It became culture made visible.

And then Judy connected it back to herself, why she keeps returning to “both/and.”

People told her for years: “It’s never either/or with you, it’s always both/and.”

“That is who I am,” she said. “I am always looking for a way to embrace the both/and.”

She laughed that the boardroom now calls her “the both-and woman”—both ALSAC and St. Jude, both research and care, both finding cures and saving children.

And she brought it to what she believes is St. Jude’s “true north”:

“It’s about the kids,” she said. “It’s about saving a life… We are always present to the true north of the little kid getting pulled around in the wagon… it’s about the child.”

‘What’s Possible”

Her advice to the younger generation came as three short imperatives:

“Be present, know yourself, and make a difference.”

Before ending, she shared one last idea—something she says she has talked about often.

“Hope is a two-sided coin,” she said. “On one side of hope is fear. On the other side of hope is possibility.”

When a family receives a diagnosis, hope is drenched in fear.

But then:

“When they cross the threshold of St. Jude, that fear… melts into possibility.”

“St. Jude is about possibility,” she said. “That is real.”

She smiled at the personal echo: “The very first tagline of my company was, ‘What’s Possible.’”