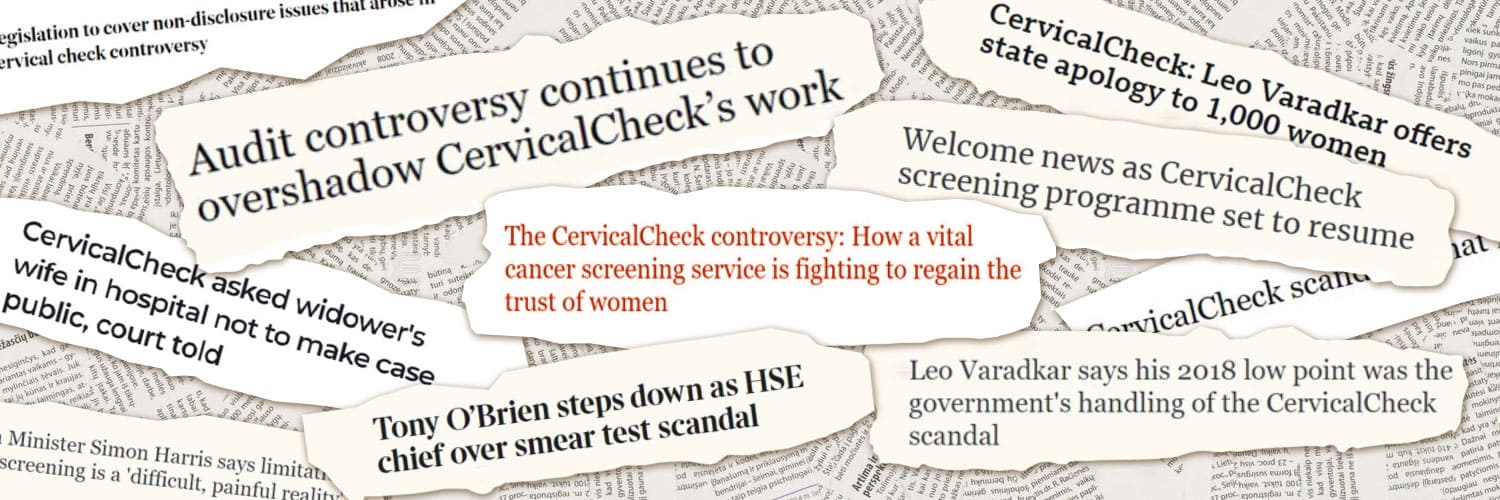

Ireland’s cervical cancer screening programme ‘CervicalCheck’ has been under the microscope since April 2018, when it was revealed that some women diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer were not told that their previous smear tests had been reviewed.

More crucially, the 221 women affected – or their families, in the cases of women who had since died – were not informed that the review concluded a different action could have been taken, either for another smear test, a smear at an earlier stage, or a cytology examination.

This revelation would lead to an escalating public health controversy that played into the Irish State’s long history of scandals in relation to women and their healthcare.

Campaigner Vicky Phelan ‒ now a familiar name in households across Ireland ‒ revealed issues with CervicalCheck after taking a High Court action against the State and the lab that examined her smear tests in 2011. She has won the Irish public’s respect and admiration for her doggedness in pursuing improvements to the programme, all while battling a terminal cervical cancer diagnosis.

Phelan – who would later be listed on the BBC’s list of the 100 most influential women of 2018 – and other women took to the airwaves to speak about their cancer diagnoses, and of the hurt of not being informed about a review into their own healthcare and medical history.

Although an independent review carried out in 2019 by gynaecologists from the UK found that Ireland’s programme was clinically sound, and a report in October 2020 found that it was operating at best global standards, the lack of transparency initially from the programme in reacting to the crisis prompted long-lasting concern among the women affected, their families, and the public about the quality of the screening tests.

Almost all of 170 recommendations to fix the programme have now been implemented, with just four left ‘in progress’, and there are new staff at the helm of CervicalCheck working to build trust back.

But there are lingering concerns about the fact that there hasn’t been a clear line from Irish authorities on what exactly went wrong and what lessons have been learned.

There are also concerns about the extent to which the Irish public understand that cervical screening is not a diagnostic test; and whether legal actions being taken against the programme due to past flaws may jeopardise the cancer screening programme’s future, and may chip away at public confidence in it.

Quality of the screening programme

The question around the quality of screening is crucial to the trust issue, and has been the subject of a constant back-and-forth between CervicalCheck campaigners and the Irish authorities. The Department of Health, CervicalCheck and many healthcare professionals have emphasised the limitations of screening in debates around the controversy about audits; studies show that if 1,000 women are screened for cervical cancer with HPV-first screening, about 20 people will have abnormal, or pre-cancerous, cervical cells.

With a HPV-first test, 18 of these 20 people will have abnormal cells found through HPV-first screening, but two people will not, and may go on to develop cervical cancer, making HPV-first cervical smear tests between 85-90% accurate.

Lack of clarity may have perpetuated a false understanding that screening is diagnostic

Due to a lack of clarity given to women in Ireland that screening wasn’t a watertight method of catching pre-cancerous cells, this may have perpetuated a false understanding that screening is diagnostic, rather than a rough tool to pluck at-risk people from the population for further testing.

“I don’t think we got out there to explain what [the controversy] was about sufficiently,” says Fiona Murphy, CEO of the National Screening Service, the body that oversees Ireland’s four screening programmes. She wasn’t involved in the programme when the controversy arose, adding that this was her opinion, viewing it “from afar”.

“People still talk about the diagnosis being ‘withheld’ from women… That’s taking a huge distance from what actually happened.” Murphy said that, of just under 1,500 women who developed cervical cancer after taking part in CervicalCheck since it began in 2008, they found 221 cases where the previous slide may have had an abnormality.

“Three quarters of those women were still at Stage 1, but potentially could have been picked up at a pre-cancerous stage. And that’s devastating for women, to know that you did all the right things, you went for your screening, but it wasn’t spotted. And unfortunately, it’s what happens in screening.”

Over 300 court cases

In December 2019, the UK’s Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (dubbed ‘RCog’) published the results of its independent clinical review of CervicalCheck over a 10-year period and found that it was “in line with internationally respectable programmes”. Out of a total of 1,038 women or their families who agreed to take part in a review of their previous smear slides, the RCog review disagreed with the CervicalCheck conclusion in 308 cases (30%). In 159 of these cases (15%), the RCog Expert Panel “considered that the CervicalCheck result had an adverse effect on the woman’s outcome”. This level of “discordance” was in line with cervical slide screening reviews in England, it said.

Despite these results, campaigners have strongly questioned the quality assurance of the laboratories that examined Irish smear slides in the years before 2018. A 2019 report authored by public health expert Dr Gabriel Scally, who is highly respected by campaigners, found that instead of six laboratories examining cervical slides, as was initially reported to Dr Scally in 2018, there were 16, due to outsourcing from the original laboratories.

Dr Scally concluded that no evidence was uncovered “to suggest deficiencies in screening quality at any laboratory”, but added that this must be understood “in a context where many of the laboratories that have been involved in screening Irish slides either no longer exist or no longer perform cytology”.

221 women were affected by the original CervicalCheck issue of not being told that an audit of their previous smear tests had been carried out, nor that the result of that review found a different action could have been taken. The ‘plus’ in the title of the ‘221+ Patient Support Group’ refers to 308 women whose smears RCog reviewed and disagreed with the original conclusion.

Solicitor Cian O’Carroll, who has represented many of the women who have taken cases against the State over CervicalCheck, said that, although there will be abnormalities missed “where it is not reasonable to criticise a screener”, “many” of the women affected by the CervicalCheck controversy had “three, four and more false negatives… that were reported as normal but in fact contained a sufficiently obvious or apparent quantity of abnormal cells such that the screener had not taken reasonable care in the performance of their duty”.

There remains a disagreement between authorities and campaigners about ‘false negative’ results – campaigners say the degree of cell abnormalities should have been obvious in some cases, while authorities say that these are within the known limitations of all screening programmes.

“The secrecy, the lack of information, the fight that we had to find out what went wrong, all of that is how the trust got eroded”

“The only way you can get the truth, because of the way the system is set up in Ireland, is to stand up in front of a judge,” says Stephen Teap, whose wife Irene was one of the 221 women, and who died of cervical cancer in 2017. “We’ll always be able to remind people that this wasn’t just about non-disclosure. The fact of the matter is that Irene went to her grave when she didn’t have to. All of that, the secrecy, the lack of information, the fight that we had to do to find out exactly what went wrong, all of that in combination is how the trust got eroded.”

What is the level of mistrust now?

In a qualitative survey carried out in 2019 and published in February this year, conducted by CervicalCheck and a HPV-focused academic research group Cerviva, 48 women who had been invited for routine screening were interviewed about the screening programme. During these interviews, all of the women “raised the screening controversy without prompting, some at the very start of the interview”. “Many adequately screened women felt strongly that they had lost the ‘peace of mind’ and reassurance which they had associated with attendance in the past and had greatly valued,” it said, adding that some also said they needed reassurance that the screening service is being “run right”.

A 2021 public attitudes survey of 2,000 people was carried out by Core Research on behalf of the National Screening Service*. In that survey, 782 women eligible for screening were asked how they felt about CervicalCheck, and 74% said they felt ‘very’ or ‘quite’ positive about the programme because they believed early detection of cancer saves lives (37% of those who felt positive towards it) or they said they had a good service or a positive past experience (26% of those who felt positive towards it).

Of the 12% who felt ‘very’ or ‘quite’ negatively towards CervicalCheck, 59% cited negative media coverage, while 25% said it was because of a fear of ‘misdiagnosis’. 14% responded they were not sure how they felt.

On the surface, this coupled with a record 318,000 women attending for their smear tests last year indicates positivity towards CervicalCheck, and that trust is being won back.

“What worries me is if women say ‘Oh, well, she went for screening and she still got cancer’ … people will say, ‘Why would I bother?’”

“I’m still worried about mistrust,” says Dr Nóirín Russell, who became Clinical Director of CervicalCheck after the controversy arose in August 2020, adding that “CervicalCheck is full of contrasts.”

“In 2021 we had a massively busy year, we knew we were going to be busy, but it was 12% above what we thought it would be, somewhere in the region of 320,000 women attending for screening. But then you’ve got over 300 court cases lodged against the screening programme. I think it’s really hard to work in the screening programme, especially at management level, and not worry about what those court cases mean for the screening programme.

“What worries me is if women say ‘Oh, well, she went for screening and she still got cancer.’ There is a real fear for me that that will turn the tide and people will start to say, ‘Why would I bother?’”

“I’m concerned that we still have quite a negative perception,” Fiona Murphy adds. And I suppose the concern is that it impacts on what women will do… What’s important for us is that women come for screening, and that screening works.

“When people read about ‘misdiagnosis’ in the media, it kind of perpetuates the idea that it’s a diagnostic test, and therefore, when it doesn’t diagnose them they worry that that’s a mistake. But also they become over reliant on that screening as a diagnostic test.”

Dr Russell also cites a slight drop in population coverage for the CervicalCheck programme, down from reaching the target of 80% for the first time in August 2017 to 78.7% in March 2020.

Standards for cervical screening

Dr David Ritchie is a Cancer Prevention Manager for the Association of European Cancer Leagues (ECL), an NGO network for European cancer societies, and a doctoral candidate at the University of Antwerp for research on evaluating informed decision-making for cancer screening participation in Europe.

“No one can say that screening is 100% accurate,” Dr Ritchie says, due to the many variables involved, the progression of the cells, and because it’s just “a snapshot in time”.

“The goal of screening programmes overall is ultimately to reduce mortality or death. It should have an effect over time in reducing the progression of disease because cancer patients are being found at an earlier stage, and over time better outcomes are more likely.”

When asked about cases where an abnormality is clearly present on a smear slide, and whether that counts as medically negligent, Dr Ritchie said that he doesn’t have the legal expertise to comment on that. But, he adds: “To me, it does sound like something that’s part and parcel of the limitations of this type of public health programme. It’s dealing with things in a state of flux in early progression and the direction of progression, which can include regression in some cases, or not having any development that would cause problems is all possible.”

In Dr Scally’s 2019 report, he wrote that people who are affected by clinical errors in healthcare generally want three things: to be told the truth of what happened and why; for someone who was involved to apologise; and to be assured that this won’t happen again to anyone else.

“If this can be achieved,” Dr Scally wrote, “many people are satisfied and they are less likely to take legal action.

“The difficulty in screening cases is to provide assurance that it won’t happen again. When millions of slides are being examined and human judgements made, it is inevitable that errors will occur.”

The risk of overdiagnosis

“Screening is like a sieve you would see in old movies about the gold rush where they are panning for gold,” Dr Ritchie explains. “And basically what you’re doing with screening, you make sure you don’t let through too many people into the next phase because you want to only send people through that pathway who actually have an indication or likelihood of an early stage of cancer or precancerous lesion or whatever it may be. Because if you send too many people through, actually, you’re causing even more harm itself and this is what leads to the major, major harm of screening: a potential for overdiagnosis and overtreatment. We have to get the balance right.”

Guidelines published by the WHO this year warn of the potential harm of cancer screening in overtreating a person: either through a false positive result, or in the detection of a cancer that would not harm the individual during their lifetime. Dr Ritchie said that, 10 years ago, there was a review of the NHS’s Breast Screening Programme, which had “the opposite issue” to Ireland’s cervical screening programme – women were concerned that they were being screened for cancer too often when they were not at-risk.

“So after that, they looked again at the booklets and decision tools and how to present the information about the inherent risks as well as the limitations of the programme – overdiagnosis, but also very small chance of false negatives.” “It’s very difficult to condense it and still remain accurate and truthful,” he said.

Dr Ritchie said that once a screening service stops having an impact on the number of people dying of cancer, and if it’s not reducing the number of cancers at an advanced stage, “this is a real problem” and is when the negatives of cancer screening may outweigh the benefits.

From 2010 to 2016, incidence of invasive cervical cancers dropped 5.3% per year, which is attributed to CervicalCheck screening

Since the National Cervical Screening Programme was established in Ireland in 2008, 74,517 cases of high-grade cell changes, 66,432 cases of low-grade cell changes and 1,727 cancers have been detected. This represents half of all cervical cancers diagnosed in Ireland over this period, according to CervicalCheck and the National Cancer Registry of Ireland.

Around 6,400 women are treated each year for high-grade abnormalities, representing women who could have developed cervical cancer if they had not been treated. After a significant increase in the incidence of invasive cervical cancers from 1994‒2010, from 2010 to 2016, there was a drop of 5.3% per year, which a 2020 HSE report on interval cancers said “is attributable” to population-based screening through CervicalCheck. The report also found that the age-standardised mortality rate for cervical cancer shows a trend to reduce mortality.

From 2015 to 2017, there was an average of 264 cervical cancer cases per year in Ireland, of which around 160 women a year were diagnosed via the CervicalCheck programme – around 60% of all diagnoses.

Providing information is key

Prominent campaigner Lorraine Walsh, who was diagnosed with cervical cancer aged 34 and is a founding member of the 221+ Patient Group, acknowledged, that though she would find it hard to trust her smear results, “a lot of good” has come from the programme, and it has saved a lot of lives.

“I do believe that we have a better system than we had then. Have we an excellent system? I’m not so sure,” she says. On where to improve further, Walsh adds: “To me, it’s all about education, it’s all about understanding, and it’s about making that available freely.”

The Core Research survey of 2,000 people carried out by the HSE indicates that there are low levels of knowledge about screening among the general public: 74% said they believe cervical screening is a diagnostic test, and 59% of respondents were not confident in spotting cervical cancer symptoms. 21% thought they did not need to worry about developing cervical cancer if they went for regular screening.

When Dr Russell is asked about communication, she says “that’s the bit we know we can really work on”, and adds that they have learned that “not everyone has the same communication need”.

Better graphics and visual aids are being developed to help explain what screening is, she says. “If someone wants more detail, we’ll say ‘here’s where you go’, if you want the scientific papers ‘here’s where you go’, but not blasting everybody with everything, because not everybody wants everything thrown at them immediately. They want to know it’s there, and want to know the information is right.”

Other work is ongoing to build trust, she adds: holding regular Zoom webinars with GPs and practice nurses; sending out a newsletter to stakeholders with reminders and informing them of any changes in the programme; holding webinars and meetings with gynaecologists; launching a new CervicalCheck website later this year, which will be easier to navigate and to find information on; and sending out tailored information to health journalists.

Work is also ongoing to set up a national laboratory for Ireland that is expected to open most likely in August this year. It will examine the majority of, but not all, Irish cervical smear slides, meaning the programme will shift from issuing tenders for laboratories to apply for.

We’re going to be super transparent and you’re going to hear about all of our incidents and about how it’s going to be sorted

Dr Russell also spoke about a new approach being taken when things do go wrong, such as when almost 200 cervical smear samples expired in the spring of 2021 due to a huge increase in the number of women coming forward for smear tests.

“For the first time since I’ve taken over the job, there was a kind of calmness, that it was like, okay, incidents happen in healthcare. And in CervicalCheck we’re going to be super open, super transparent and you’re going to hear about all of our incidents and you’re going to hear about what the plan is and how it’s going to be sorted. I think that builds trust.”

When asked whether they can rebuild and maintain trust in CervicalCheck, NSS chief Fiona Murphy says: “I am concerned that I think that negative perception will last for a very long time. It’s a hard thing to turn away. But what we can do in the meantime, is to make sure that people’s experience is good, and try to be more public and present about telling people that actually the service is very good, it’s very well run, you’re better off coming even if you’re worried about coming.

“But also, be more honest about what screening is and it isn’t – that’s probably our biggest gap right now.”

Murphy adds that in the first few years of the CervicalCheck programme, it was said “in small print almost, that screening doesn’t find every cancer, but in an effort to encourage people to come forward, that tended to be downplayed.”

Patient advice is ‘like gold dust’

The patient‒public panel has been called “gold dust” by CervicalCheck staff in building trust and confidence back among the public. One of their patient representatives is Grace Rattigan. After years of encouraging women to attend for their smears after her mother Catherine died of cervical cancer, in 2018 Grace found out that her mother was among the 221+ women affected by the CervicalCheck controversy.

“I was a bit lost,” she says, of when the controversy first broke. “I knew how important screening was, but it felt very difficult to be constantly on social media saying ‘Go for screening’ when this was happening. It’s so conflicting.”

She was later invited to be part of the patient group to oversee the implementation of the 170 recommendations arising from the Dr Scally’s report, which she said gave her a chance to provide feedback, to make sure things were being fixed.

She said that she has confidence that there is a best-practice screening programme in place now. When asked whether the patient group has helped build trust, she says “absolutely”. “I’m only a small cog in that wheel, but most people who have followed me for years, see ‘Oh, well, Grace is in there now’, and I’m to be trusted. I’m not gaining anything from this. I don’t work there, I don’t get paid for anything. It takes away that us-and-them thing.”

She said that the patient advisory group could be useful in building trust in other forms of healthcare too, particularly around women’s health. “It’s a funny situation, because it’s one of those situations where good comes from bad. We shouldn’t have had to get to this stage for this to happen, but it’s a bittersweet situation – that’s exceptionally hard for me to say when I’ve lost my mam.

“But it has actually shone the spotlight on women’s health a lot in the country. Between this, and Repeal [abortion vote] in 2018, I think it’s done wonders in that sense that people can think, ‘No, we’re gonna speak up a little bit here now’.”

This article was funded by a grant from the European School of Oncology to fund cancer journalism. It was first published by the Irish online news website TheJournal.ie, on 18 April 2022, and is republished with permission. ©Gráinne Ní Aodha and The Journal.

* Figures from that survey were released to The Journal for the purposes of this article