A new survey of 1,871 people living with cancer in the UK and US has revealed significant differences in the terms that they would like to be used to describe themselves. Descriptive terms such as “victim,” “sufferer” and “cancer stricken” were considered to be overwhelmingly negative, whereas terms such as “warrior”, “hero”, “thriver” and “on a cancer journey” received a mix of positive and negative responses.

Over two-thirds of those surveyed in the ‘My Cancer My Words’ project believed that the use of language impacts them, or others living with cancer. The study simultaneously surveyed 142 healthcare professionals working with people with cancer, and 88% agreed that the terminology they used was important.

The survey also highlighted notable difference in preferences between people in the US and the UK – with those from the UK tending to perceive all descriptive metaphors as likely to negatively impact their ability to make treatment choices. US respondents, on the other hand, were more comfortable with metaphors and particularly favoured the terms “survivor” and “fighter”, with over half of respondents saying the terms would positively impact their treatment choices.

“Someone’s sense of self is so much a part of their well-being that we can’t ignore the words we use in talking about people living with cancer”

The study was the initiative of drug company Novartis, working in collaboration with an expert steering committee. “We really need to get a sense of how we best support people with cancer,” said steering committee member Claire Saxton, who is Executive Vice President at Cancer Support Community, a Washington DC-based patient support organisation. “Someone’s identity, and someone’s sense of self, is so much a part of their well-being that we really can’t ignore the words that we use in talking about people who are living with cancer.”

Our terminology

This article uses the terms “patient” and “survivor” to describe people with cancer. We recognise that not all people with cancer or those who have had cancer will agree with this choice of terminology.

Christopher Recklitis, a clinical psychologist and Director of Research and Support Services for the Perini Family Survivors Center in Boston, said that the survey data reflected his own experience as a clinician and his knowledge that there are no terms that work for everyone. “This survey reminds us that we don’t automatically know what each patient prefers and we have to be okay with that, keep communication open and respect where people are at with their identities,” he said.

“If the patient wants to call their experience a journey, I’m 100% behind them,” said Recklitis, who was not involved in the survey. “But if you are the doctor who sent them for surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, with all of the side effects, you don’t get to call it a journey. Perhaps they call it a hellscape. We don’t know, so unless told otherwise by the patient, I tend avoid colourful, metaphorical language.”

The descriptive words and phrases that participants reacted to in the survey were chosen based on previous studies, use in media and input from patient representatives, linguists and clinicians. Perceptions of the words were similar across age groups, genders and cancer type and stage. But it was when socioeconomic factors such as income and education level were taken into account that differences tended to emerge.

“It didn’t surprise me… how passionate some people are about making sure that the words that they choose are used for them”

The difference in attitudes to terminology between the UK and the US is hard to explain, said Saxton. “But it didn’t surprise me how diverse people people’s preferences are in terms of the words used to describe themselves, as well as how passionate some people are about making sure that the words that they choose are used for them.”

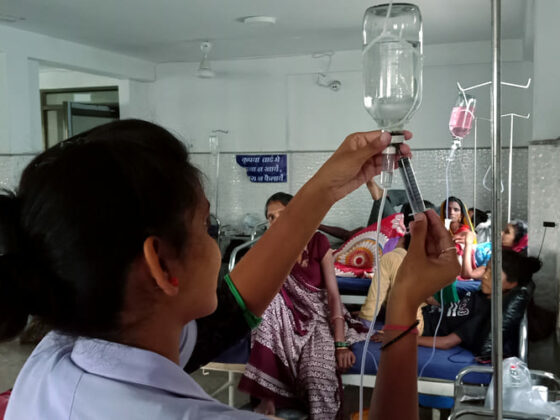

Meanwhile, another study has also pointed to the influence of language used on the care of cancer patients. A study published in the Journal of Cancer Policy has found that clinicians using subjective and “minimising” terms may undermine patient-centred care and hinder comprehensive treatment strategies. The language used to report toxicities of cancer therapies in clinical trials can minimise side effects, with terms like “safe,” “tolerable,” and “well-tolerated” being interpreted differently from person to person. This can make it difficult to compare results across trials as well as downplaying the risks and limitations of treatments.

The authors say that language describing patients “failing treatment” can no longer be considered reasonable.

Claire Saxton said that when she first came into patient advocacy, it was still regularly said that patients had “failed” therapies. “We still haven’t fixed that completely. But there are more and more healthcare providers who are much more likely to use words like ‘The therapy failed you’ rather than ‘You failed the therapy.’”

Christopher Recklitis also points to significant recent discussions about use of the term “cancer survivor”. “There are people who feel very strongly that the term cancer survivor should apply to everyone from the moment they are diagnosed and I definitely see that perspective. But I also see that some people having active cancer therapy don’t think that the term ‘survivor’ is appropriate until they’ve completed their curative therapy and they expect to survive for some significant period of time.”

The term “cancer survivor” also receives mixed reception from people who have metastatic cancer where, while treatment advances mean that they have a good chance of living with their cancer long-term, ‘cure’ is unlikely.

“I think a good question to ask, perhaps in a future survey, is who has permission to use these terms?” said Recklitis.