Precision medicine is transforming the way we treat cancer. Oncology is evolving from treating purely on the basis of a broad indication to a tailored approach that is based on a tumour’s molecular characteristics, and usually requires complex combinations of therapies. But precision medicine doesn’t just affect approaches to treatment, it also requires a change in the approach to patient care, says Johan De Munter, nurse manager at the University Hospital Ghent Cancer Centre and president of EONS, the European Oncology Nursing Society. “Precision treatment is something we cannot achieve if we don’t work in a multidisciplinary approach. We need every health care professional’s expertise and competencies.”

Precision nursing is an emerging concept that De Munter highlighted in his closing speech at the EONS conference in 2021. He talked about the concept of ‘precision health’, which “uses big data and patients’ individual variables to create and apply a programme of prevention, detection and intervention that is tailored to an individual.” Cancer nurses, he argued, “can play a key role in exploring the possibilities of precision health to improve the treatment for cancer patients and reduce the cancer burden.”

For Yvonne Wengström, cancer nurse and Professor of Nursing at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, precision health and precision nursing are about personalising all aspects of healthcare, with an emphasis on supporting patients to have the best health possible. “With the increase in the precision of the treatments we are giving, we also need to increase the precision of interventions to support patients to manage the treatment,” she says.

Cancer nurses are important touchpoints in contact and communication with patients, as de Munter points out. They complete comprehensive assessments, examine a patient’s lifestyle, assess symptoms. This ‘symptom science’ is an area in which nurses play a particularly important role, says Wengström. “We have a lot of symptom science knowledge within nursing. Especially with new drugs, it is extremely important to understand what kind of symptoms patients are going to have and how we are going to support patients to handle this treatment.”

In this regard, she urges a greater use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in daily nursing practice, as well as more research into which PROMs might be appropriate for which symptom or side effect. “There might be specific PROMs required for a specific treatment or symptom, but we have just started our journey towards using PROMs.”

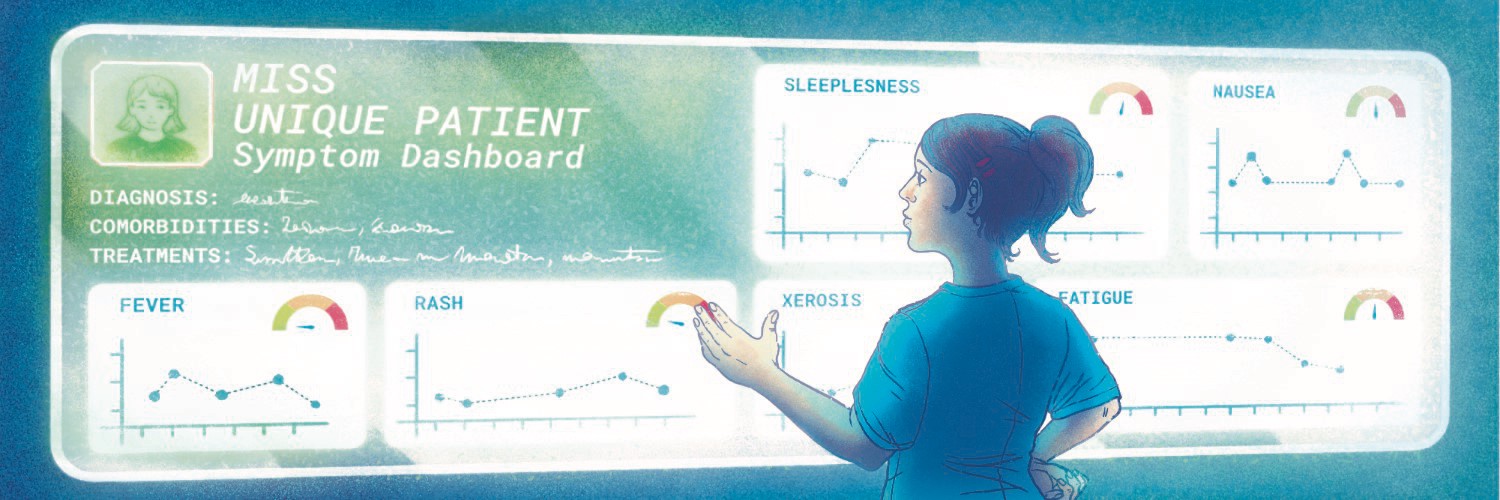

Assessing which of multiple treatments might be responsible for a given side effect, and which concern is the most pressing, can be particularly difficult, says Wengström – especially as symptoms like anxiety, fatigue and sleep disorder are interconnected. She envisages a type of control panel for each patient that provides immediate feedback at the level of symptoms. “We need to get a dashboard up for each patient and see: What is the main concern right now? Why is an intervention not working? and immediately follow up. If we have this knowledge and direct feedback on symptoms and side effects, we can be much more proactive.”

“We need to get a dashboard up for each patient and see: What is the main concern right now? Why is an intervention not working?”

Wengström and de Munter both recognise, however, that patients are not just passive recipients of care – they play a critical active role in helping manage their own health. As the health professionals who interact most closely with patients, and on a regular basis, nurses have a key role in giving patients the tailored support, advice and information they need to do that as effectively as possible, says de Munter. “One of the biggest tasks of cancer nurses is to increase the healthcare knowledge of patients, so they can use it in self-management, as precision healthcare has to be adapted to a patient’s lifestyle, the psychosocial environment and other contexts.”

Wengström adds that cancer nurses are important to increase health literacy and enable patients to play a part in creating personalised strategies that work for them, and to make clear decisions about treatment. “In the future, we will need to include patients in a totally different way, right from the beginning, in developing how we care for them, what is meaningful and important to them – wherever they are in the cancer trajectory”, she says.

While involving patients in their own self-care is desirable in itself, Wengström argues that it is also becoming a necessity, due to the shortage of nurses, which will worsen in future. “We have a steady decrease in nurses, and no matter how many we educate now, we are not going to be able to catch up with this decrease,” she says. “We need to find new ways to support patients and their families, because we are going to expect them to care much more for themselves.”

If that approach is going to work, Wengström argues, such nursing staff as we do have will need to understand treatment in a much deeper way, so that they can educate both patients and their families in how to care.

Nursing education for the precision era

Wengström worries that current curricula for training nurses often fail to give them the knowledge they need to deliver precision care. “I don’t think that in many countries, precision medicine is part of nursing education. We have a generation of nurses coming in who don’t really know what it is and how precision medicine is going to impact their job in the future.” She argues that nurses do need to understand precision medicine in some depth. “If they don’t know the mechanism, how are they going to treat symptoms or side effects and support patients?” The Karolinska Institute, where she works, is currently developing education for nurses about precision health, including web-based training as well as seminars and workshops around patient cases.

“We have a generation of nurses coming in who don’t really know what it is and how precision medicine is going to impact their job”

De Munter agrees that education and training need to be rethought to enable nurses to play their full part in delivering precision oncology as part of a multidisciplinary team. “One mission of EONS is that all patients can have treatment from a well-trained, educated cancer nurse that works in an evidence-based way and has the ability to be involved in the multidisciplinary team, and to deliver high quality personalised health care,” he says.

Realising this vision has some way to go in many areas of Europe, De Munter acknowledges. “We know there is a massive discrepancy between cancer nurses’ roles across Europe.” Traditionally, the more northern countries in Europe are more advanced in cancer nurse roles, he says – a disparity that was highlighted a few years ago by the findings of EONS’s RECaN (Recognising European Cancer Nursing) project, which compared roles and recognition of cancer nurses across several European countries. The research showed that, while the UK and the Netherlands have clinical nurse specialists, as well as different roles for nurse consultants who play a role in precision medicine, that level of recognition is lacking in many other European countries, particularly in southern Europe and the Balkans. In these countries, says De Munter, “nurses have a massively important role, but are not recognised as serious in their role, and as bringing added value to the treatment… That’s why it is so important we invest in education across Europe.”

To strengthen the training of nurses, specifically for future challenges in oncology, EONS is participating in an EU-funded project, INTERACT-EUROPE, which brings together many stakeholders, including the European Cancer Organisation and European School of Oncology, around efforts to develop a European inter-speciality cancer training programme. “In this framework on cancer education, we define the minimum basis of evidence-based knowledge that nurses must acquire so that they can be involved in the multidisciplinary approach, to create precision healthcare for patients with cancer,” says De Munter.

Getting education and collaboration right for precision medicine in oncology could be just a first step towards a more universal involvement of nurses in precision health, adds Wengström. “Cancer is at the forefront of precision medicine, but precision health is increasing in other diseases as well.”

Illustration by: Sara Corsi