If you are interested in cancer care in low and middle income countries we also suggest:

Africa

- Regional cancer centres to boost access to cancer care across Uganda

- Not just a climate issue: cutting cancer rates through cleaner cooking fuels in Africa

- Cancer drugs for Africa… from Africa?

Asia

- Pooled procurement of drugs saves millions for Indian cancer centres

- Precision medicine for all!

- AI-generated radiotherapy planning could boost access to high-quality treatment across the globe

Latin America

- Geriatric oncology: how physicians in Latin America are personalising treatments and changing attitudes

- Unpaid women carers: recognising their contribution and their needs in Latin America

Calamities and war zones

Rahul Jain and his mother Shashi were in Pune – 1,000 km from their home in Ashoknagar, in the neighbouring state of Madhya Pradesh – when they were told there was no hope. They had undertaken the long journey together to get treatment for Shashi’s breast cancer. But after her primary tumour was removed, they were informed that the cancer had spread and was now stage IV. So Rahul brought her home.

He’d been advised that palliative chemotherapy could relieve some of her symptoms and slow disease progression, but that was only available at a private hospital in Pune, at the cost of Rs. 1 million ($12,000), which the family could not afford. The government hospital near their home had told Rahul that, given the advanced stage of his mother’s disease, there was nothing they could do. Shashi was getting steadily more unwell and had a severe cough.

In desperation, Rahul travelled to three different states for herbal medicines that could give her relief. When he heard about Chandramauli Tripathi and the work he was doing with cancer patients in Ujjain – a city in his home state, only 300 km away – he rushed straight there.

“I spoke to sir [Tripathi] on the mobile, he saw her reports and said it is advanced cancer, but they will try treating her,” Rahul told Cancerworld. Now, on her fifth chemotherapy cycle, Shashi Jain is feeling much better.

The Jains are among thousands of families finding hope and treatment at Ujjain’s Cancer Care Centre. The facility doesn’t look like much – it’s a British-era building on the opposite side of the road from the Ujjain District Hospital, with an outpatient department at the front, connected by a long corridor to a ten-bed daycare centre. There is construction work going on to build an operating theatre. But this unassuming building is where cancer patients across the Ujjain district and other districts in Madhya Pradesh come when they have spent all their savings and have been told they have run out of treatment options.

Starting in 2014, the centre has treated more than 6,000 cancer patients for free. This is unusual, because cancer is not treated at India’s district hospitals, which are the closest public tertiary care centres to most rural residents. That’s because the focus has always been on infectious diseases and maternal and child healthcare.

Cancer is usually treated only at larger specialised centres in major cities – or in private hospitals. This is why cancer treatment in India is inaccessible for most of the population. It is also helps explain why most cases are not detected until they reach advanced stages.

This highly centralised model began to change when Dinesh Pendharkar – a medical oncologist and now the Director of the Sarvodaya Cancer Institute, in Faridabad (Delhi) – launched a ‘District Cancer Care Programme’, starting with Madhya Pradesh. Working pro-bono, he trained the existing medical officers posted in district hospitals, most of them with only MBBS degrees, in the basics of cancer and cancer care – including early diagnosis, ordering investigations, counselling patients and delivering chemotherapy – to enable patients to access cancer services without having to travel to distant cities and spend tens of thousands of rupees.

Through hard work and advocacy, the programme has now spread across India. Pendharkar and his team have trained more than 200 doctors in eight states, working in 151 operational district cancer centres like the one in Ujjain, providing cancer care to a population of 380 million.

The model is now attracting strong interest across the globe in countries looking for ways to improve access to cancer care among their own populations.

How it started

Why was an oncologist from the city interested in solving the cancer challenges of India’s hinterland? Dinesh Pendharkar says that it was his frustration at seeing patients delay or forgo treatment due to limited access, money, time, and family support that prompted him to search for ways to bring cancer care close to their homes. He chose district hospitals because they are closest to the patients and the tertiary care units near villages. He wanted to ensure that the most essential cancer drugs would be available in these hospitals free of cost.

The idea came to him 2003, while working at Batra Hospital – a private hospital in Delhi. The hospital is one of hundreds of facilities empanelled to provide care for the massive workforce of Indian Railways, and every day large numbers of patients would visit the hospital for chemotherapy. Pendharkar wondered whether Indian Railways could save money by providing chemotherapy in the organisation’s own hospital, under the supervision of specialists.

He trained a doctor posted in the Indian Railways hospital in the basics of chemotherapy, and Indian Railways procured their own medicines. Within a few weeks, the centre proved to be a success, and the four-bed centre was expanded to six beds. With the money saved, they were able to install air conditioning and all modern amenities. The doctors there are able to consult specialists over cases where they feel advice is needed, but otherwise the care is delivered by their own medical staff: “This centre now conducts over 100 chemotherapies a day,” says Pendharkar.

The opportunity to roll out this model within the public health system came in 2014, in the form of a chance encounter with the health secretary of Madhya Pradesh, who wanted to start treating cancer in the districts (in India, responsibility for healthcare lies with each state). The initial plan was to run a pilot in 12 districts. Pendharkar started by inviting medical officers to Mumbai for a month-long training under him. The Madhya Pradesh government went ahead and publicised that cancer would soon start to be treated at the district level. Sceptics, however, questioned whether doctors could safely provide care for cancer patients based on only one month of training, says Pendharkar.

So a team of specialists, including medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pharmacists, and more, were sent by Madhya Pradesh officials to test these newly trained doctors. They were impressed to find that all of the doctors passed written tests and vivas, where the examiners posed questions in person. The state officials, says Pendharkar, were assured that their patients were in good hands.

“Pendharkar has pushed the envelope in terms of the kind of services that a district hospital can provide”

Tripathi, the ‘nodal cancer officer’ from Ujjain, was among that first cohort of doctors trained up by Pendharkar, and has since become his trusted deputy, training and supporting staff running the model across the states.

Gauri Singh, who took on the role of health secretary of Madhya Pradesh in 2016, two years after the launch of the District Cancer Care Programme, says, “[Pendharkar] has pushed the envelope in terms of the kind of services that a district hospital can provide, and has proven that you do not need a MD degree to provide chemotherapy – any doctor who is willing to work can do it.”

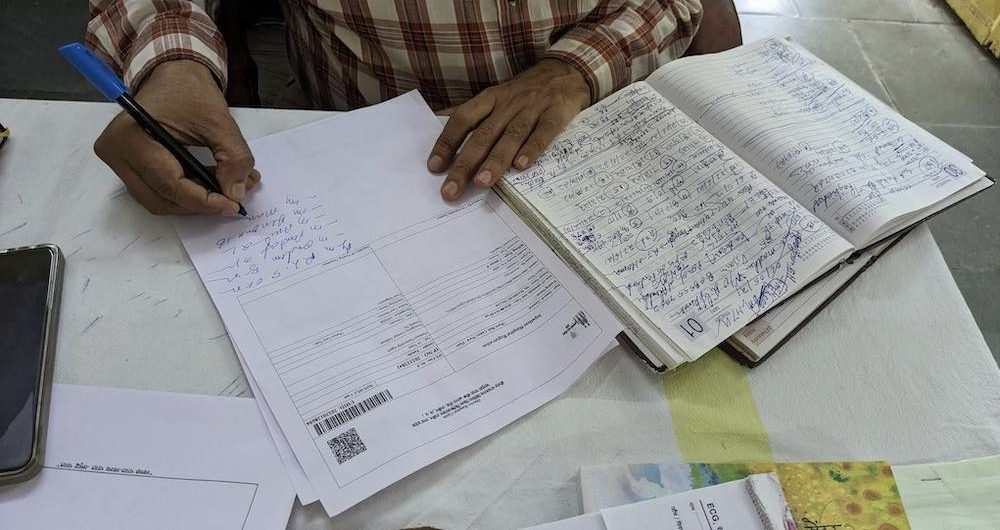

Photo credit: Swagata Yadavar ©

After the successful pilot, the programme was implemented in all 51 districts in the state within a year.

With a population of more than 72.5 million people, Madhya Pradesh is the fifth largest state in India – but it is only one of 28 states, each of which make their own decisions about how to run their health systems. Pendharkar therefore spends considerable time advocating to convince other states to adopt the model.

The first state to do so after Madhya Pradesh was Odisha, followed by Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Gujarat – with a combined population of around 380 million.

Pendharkar’s work has been documented in the ASCO Educational Book, as well as in the Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics and elsewhere. A 2021 paper in the Journal of Clinical Oncology showed how the district cancer care programme was able to continue providing crucial care for cancer patients during the Covid pandemic lockdown.

How it works

Pendharkar calls his model, ‘techno-mentoring,’ where the doctors are mentored both online and in person. In the one month of in-person training, which is now led by Pendharkar or Tripathi in Ujjain, doctors learn about cancer, oncology drugs, the investigations to order, treatment protocols, and – most importantly – how to write the medical summary. This is followed by mentorship by telephone and video conferences and virtual tumour boards, backed up by an active community through a WhatsApp group, which Pendharkar says is available to the doctors “24/7”. This gives them confidence that they can safely deliver cancer treatments, he says, knowing they can always consult a specialist if they feel they need advice.

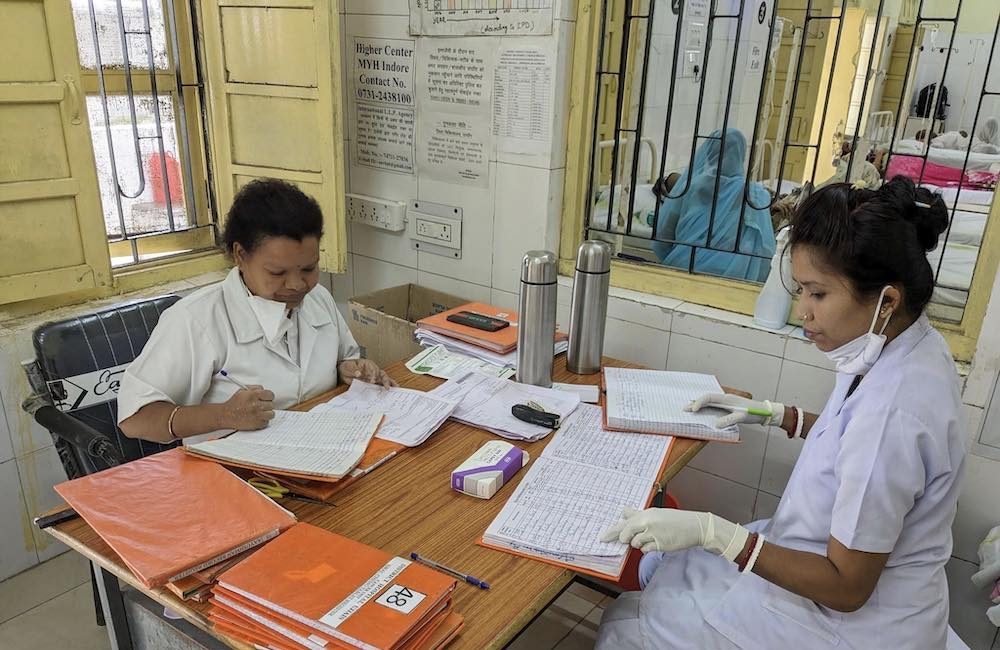

Each state takes responsibility for procuring 25 cancer drugs, which are paid for from their own health budget, and which they can select from the essential cancer drugs list. The state is also responsible for providing a few beds together with trained nurses to work at the district cancer centres.

To monitor quality, nodal cancer officers conduct ‘cancer camps’, where they consult the patients in the presence of Pendharkar

“The idea is not to replace cancer specialists, but to assist cancer patients,” says Pendharkar. In addition to delivering chemotherapy, the trained doctors do early detection, order investigations, counsel patients, refer them to the right hospital, and provide chemotherapy and palliative services in the hospital. After the training, the nodal cancer officers are expected to conduct ‘cancer camps’, where they consult patients in the presence of Pendharkar, to ensure that they are all being managed appropriately.

Attending these cancer camps, to ensure the quality of the care, means Pendharkar often has to take more than 10 days a month off from his private hospital job. To cover the large distances in areas with poor transport connections, Tripathi and Pendharkar both tend to travel at night, and cover three to four neighbouring cancer camps during the day, which is how they succeed in covering most of the districts of their newly trained doctors.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Chandramauli Tripathi

Ajay Parmar, District Nodal Cancer Officer at Junagarh, in the state of Gujarat, says it was during his initial six months in the role that he really needed Pendharkar’s guidance. After that he felt he was well versed and could manage the 400 or so patients who attend his outpatient department every month on his own.

The biggest difference in the service they provide, compared with the private sector, he says, is how they communicate with patients. “We tell patients what stage they are, and what kind of treatment will work for them. This information is not given to them anywhere else, and it gives peace to the family,” he told Cancerworld. At Parmar’s initiative, their district hospital is the only one in the state of Gujarat to run a 30-bed palliative cancer centre, where patients who are suffering complications or who need pain management can be treated. “Our patients are convinced that they won’t get this kind of time or emotional support anywhere else,” he says.

The respect from patients and their superiors is one of the reasons why trained doctors are so keen to do this work, says Pendharkar. They become the go-to person for everything to do with cancer – from getting patients railway concessions to travel, to securing them referrals to specialist centres or palliative treatment at home.

“Our patients are convinced that they won’t get this kind of time or emotional support anywhere else”

Also important is the central role played by nursing staff, who are given responsibility for administering oral drugs, and are able to specialise purely in caring for cancer patients. Tripathi has trained more than 400 nurses from different states since the beginning of the programme – including Kachan Kahar Mehra, a nursing officer who has worked in palliative care at the Ujjain cancer centre since 2018. “We are not rotated out of cancer wards, so patients and nurses form an emotional bond,” she says. She loves the work, which she says gives her job satisfaction and a sense of service that she never felt working in other departments.

The right care, at the right place and the right price (free)

Cancer is usually detected in advanced stages in India where the prognosis is poor. The tragedy is that families frequently end up spending money they don’t have, to secure treatment that may offer little benefit, and frequently takes patients and carers far from the comfort and support of their own homes.

“It is very easy for a family of a cancer patient to move from being above the poverty line to below the poverty line – we do not want that to happen,” says Tripathi.

Most of the patients cared for at the outpatient department of the Ujjain Cancer Centre have an advanced stage of cancer. “Many of these patients live one or two years (under their care), [even though] they were sent away from other hospitals, saying there is nothing to be done,” says Tripathi, adding that palliative chemotherapy is not made available to most patients in India who need it.

This model is also meeting the need for home-based palliative care for cancer patients that is unavailable in most parts of the country

Patients seen by Tripathi are given prescriptions for chemotherapy on the spot, and they receive chemotherapy and can go home by 2 pm the same day. It’s the patient’s convenience that is of utmost importance, says Tripathi. He advises patients to call him the day before they plan to visit, so that he can manage his caseload in a way that minimises waiting time.

This model is also meeting the need for home-based palliative care for cancer patients that is unavailable in most parts of the country. The trained doctors counsel family members, and advise them where to contact a local physician or nurse, who is then advised by the cancer centre on how to treat the patient in the comfort of their home. “A family easily spends Rs. 30,000 [$362] per day in an intensive care unit of the private hospital,” says Tripathi. “Most Indian families cannot afford to do that.” He says it is because they are able to offer this kind of service that families keep in touch with them long after the patient has died.

Photo credit: Swagata Yadavar ©

Fixing the wider system

While the district cancer centre model seems to be highly effective in widening access to many aspects of cancer care, patients do still have to travel long distances to access radiotherapy and surgery. Despite having a population of more than 70 million, there is not a single linear accelerator (LINAC) in a government hospital anywhere in Madhya Pradesh, so patients needing radiotherapy are forced to go to the private sector or go without. And with little support or guidance available to help them navigate the system, patients often find themselves sent from one centre to another to access treatment.

Many patients Cancerworld spoke with at the Ujjain outpatient department also said that they had not been able to use their Ayushman Bharat cards [government health insurance cards for the poor], to pay for the diagnostics and treatment they received before they came to Ujjain, and had been obliged to pay from their own pockets.

“Pendharkar has demonstrated that the model works, which is a giant step forward”

Furthermore, the district cancer centres do not always get the support they need from the state administrations, says Pendharkar. He worries that state health departments lack a sense of ownership of the programme. There is a problem with high-performing doctors being transferred out of the cancer hubs, while underperforming doctors are not replaced.

And despite the undoubted success of this model, which, in Madhya Pradesh alone, has delivered treatment to more than 60,000 cancer patients over ten years, and to around 190,000 patients across the eight states where it is currently in operation, there’s still a long way to go before it is rolled out to the entire country.

One of the crucial questions is whether the model would continue to function without the constant support and advocacy of Pendharkar? “Nobody will need me if we create a system,” Pendharkar. Like the Railway Hospital, which would treat cancer patients on its own, district hospital doctors would be able to treat cancer patients by themselves, under the guidance of an oncologist.

Former Madhya Pradesh health secretary Gauri Singh believes the dramatic change involved in bringing cancer care to districts required a champion like Pendharkar, and says he has demonstrated that the model works, which is a giant step forward.

Pendharkar himself is optimistic and excited that some states are building on his work. For example the eastern state of Odisha, which is mineral rich but underdeveloped and poor, has already pledged $120 million (Rs 1000 ‘crores’) for creating 11 comprehensive cancer care units in the state, so that “no patient from Odisha needs to travel outside the state for cancer treatment.” It seems Pendharkar’s endless advocacy could be showing results.

The opening illustration shows Dinesh Pendharkar (left) and Chandramauli Tripathi (right) jointly consulting patients at the Ujjain Cancer Centre, Madhya Pradesh. Photo credit: Swagata Yadavar ©

India’s rural population needs better access to cancer care

Cancer is the fifth leading cause of death in India. There were an estimated 1.3 million cancer patients, with 851,000 deaths, in India in 2020 according to Globocan. This number is expected to double by 2040.

Nearly 95% of cancer care facilities in India are in urban areas. While the incidence of cancer in rural India is half that in urban India, the mortality rates are double.

Most cancer treatment is funded out of patients own pockets and most seek treatment in the private sector, where the cost is much higher than in the public facilities.

Cancer is a leading cause of catastrophic health spending, distress financing and increasing expenditure before death in India.

Approximately 40% of cancer costs are met through borrowing, sale of assets and contributions from friends and relatives.

3 comments

Dr. Pendharakar has developed phenomenal program for cancer care in under privileged population and setup an example where there is will there is way.

Congratulations

This is such a incredible step, Cancer care facilities can be provided in such way, never thought about this. This is just wow.

Great

Comments are closed.