In the devastating health situation in Gaza, with a population continuously displaced, short of food and shelter, and living in trauma and fear, cancer patients need all the support they can get. Yet even when international aid can cross into the territory, the specific needs of cancer patients are overlooked.

What remains of Gaza’s Cancer Centre is now being run from a corner of a makeshift building in the grounds of the European Hospital, in an exposed area of the outskirts of Khan Younis.

The team – now reduced to one-fifth of its full complement of 250 staff – continue to care for cancer patients, despite being constantly displaced from one location to another. But lack of equipment and medicine means they are unable to use their skills and knowledge effectively, while the option of referring patients for treatment abroad, which worked for some in the early months of the war, came to a halt with the closing of the Rafah crossing in May. The situation is desperate for patients and staff alike, says Sobhi Skaik, Director of the Cancer Centre. “Always in our displacements, our patients are coming daily to the clinics, asking about care, about medicines, about referrals, and unfortunately, we cannot answer them. What to tell our patients? We are sorry we don’t have it? What does the word ‘sorry’ mean for a cancer patient? They will die in indignity. We cannot help.”

International aid agencies, understandably, focus on immediate trauma and the needs of children, but there are increasing calls for them to broaden their agenda to include care for people with non-communicable diseases, including cancer.

Pharmacist Suha Suleiman, who is the Cancer Centre’s lead for pain control, says “The humanitarian organisations and institutions are not so interested in cancer. Any projects involving [our] team and cancer patients are at the end of list.”

Cancer professionals are particularly frustrated, as they know that Gaza was on the brink of transforming oncology services for the better when the conflict broke out.

Gaza’s first national cancer centre had been established just south of Gaza City in 2020, at the Turkish Palestinian Friendship Hospital. This large, modern healthcare facility had originally been intended as a teaching hospital for the Islamic University of Gaza, but had first come into commission as a Covid hospital during the pandemic, and was afterwards assigned as a specialist cancer centre.

Plans had been finalised with the Health Ministry and international health agencies to develop the facility into a comprehensive cancer centre that would not only centralise diagnostics, treatment and holistic care services for adult cancer patients, but would also give Gazan patients access for the first time to radiotherapy and radioisotope scanning without having to travel to the West Bank or Egypt. The operational plan includes developing integrated palliative/supportive care, with a clinical nutrition programme, a psychiatric team, and palliative care and pain management unit with a mobile palliative care team. Under the plan, the centre also assumes responsibility for prevention and early detection programmes, as well as research and training.

Displaced services and desperation

All those plans are now on hold. With no electricity, no fuel for generators and having taken a direct hit that blew a hole in the third-floor admissions ward, on the night of November 1st 2023, Cancer Centre staff and patients were forced to evacuate the Turkish hospital premises, leaving behind the facilities and many supplies.

Skaik recalls the scramble to reach safety. “All the hospitals were flooded with injuries and displaced people. We couldn’t find a proper place for our patients. I had been calling the ICRC (Red Cross), WHO, UN – all of them – but those agencies could not help us at that time. We were obliged to leave the hospital forcibly, and under very unsafe circumstances. Ministry of Health ambulances came to pick up the patients and the staff with them. Some were shifted to Al Shifa hospital [close by, in Gaza City], some to Shuhada al Aqsa Hospital [in Deir al Balah, central Gaza].

“This night we lost four patients. Some were in intensive care, and there was no proper care for those patients; no professionals who could take care of them.”

“Each time the place we go to is not suitable for care of cancer patients, but we try to tailor the space, and find an area for chemotherapy”

The next morning, saw the start of a continuous series of displacements. They shifted first to the Dar Es-Salaam hospital in Khan Younis [southern Gaza]. That became unsafe, so they shifted to the Nasser Hospital complex, also in Khan Younis. When that became unsafe, they moved further south, finding a corner in the Abu Yusuf Al Najjar and then the Al Zahra clinic, both in Rafah, which had been designated a safe zone. When the military operation started in Rafah, they had to move back to Khan Younis, which is where they currently find themselves in the grounds of the European Hospital. “We have been in displacement, going from one place to another, at least nine or even 10 times. Each time the place we go to is not suitable for care of cancer patients, but we try to tailor the space in the room, and find an area for chemotherapy, if we can get hold of it. The patients come with us each time. My essential staff together with the remaining patients.”

With each displacement, they would flag up their new location on social media. Staff were able to reach some patients by phone.

About 10,000 patients had been in active management or follow-up on the books of the Gaza Cancer Centre before it was evacuated. Many of those patients also had to keep moving from one ‘safe zone’ to another, and were being lost to the service. In addition, 2,000 new cases are typically diagnosed every year, and these unknown new patients are not being formally diagnosed, because the entire health service is on its knees, lab reagents are lacking, both of Gaza’s consultant histopathologists were killed, and diagnostic referral pathways have collapsed.

Cancer care services survive against the odds

In their corner of the makeshift clinic in the grounds of the European Hospital, the remnants of the cancer centre staff continue to provide what services they can, with almost no support from international aid agencies. Suleiman describes the challenge: “Our patients are very, very fragile – the war and loss of loved ones and homes and displacement – and having cancer makes their suffering more and more.”

Many patients have been living for months in tents in overcrowded encampments with a very poor diet and limited access to clean water. “Most of our food here is canned or processed meat. No vegetables. No fresh meat or fruit. All of these items have almost disappeared from the market.”

Simply being able to provide nutritional and hygiene support could make a big difference, she says, particularly for patients who have been through surgery or need chemotherapy.

Simply being able to provide that nutritional and hygiene support could make a big difference

Lack of analgesics is a huge problem. Many of the oral morphine drugs are not available, and oncologists are obliged to use intravenous morphine, which is not recommended in most cases. Even nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like celecoxib and diclofenac are not available. The pain team are obliged to prescribe gabapentin, which is designed for neuropathic pain, and is not suitable for cancer patients.

“Many, many patients now depend on morphine IV and on gabapentin tablets,” says Suleiman, “But we have no other choice. What can we do?”

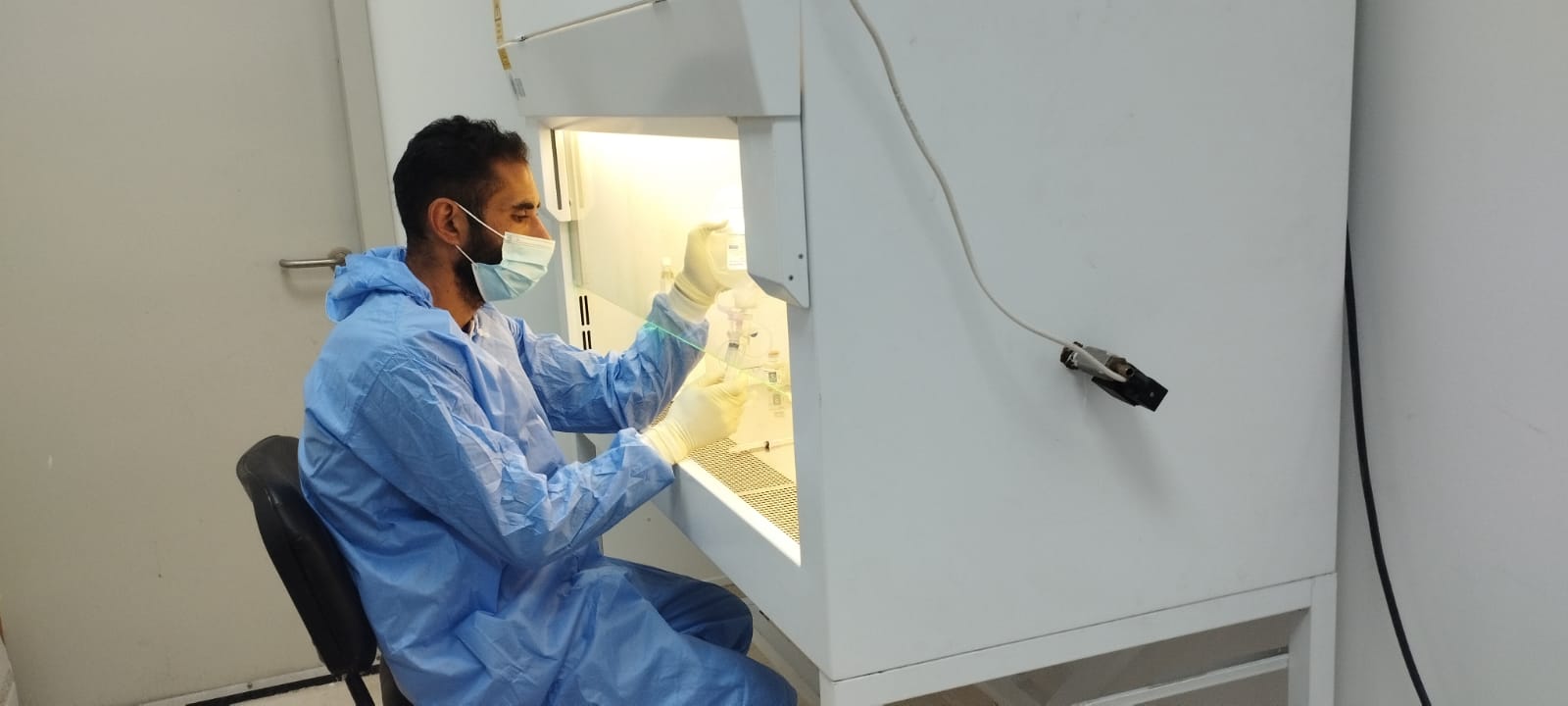

There has been a slight improvement in access to some treatments for breast cancer and to a lesser extent for colorectal cancer. The team innovates and one of the skilled pharmacists prepares the medications in a room they have made “as sterile as possible”.

However, lack of basic logistics makes everything less safe and more onerous and the health ministry computerised system for health records has collapsed.

Suleiman emphasises the mental and emotional stress her patients are under. “They need psychological support. Spiritual support.” Among the 50 strong staff are many who had undergone palliative care training as part of the Cancer Centre’s capacity building programme, and Suleiman is proposing that they start offering that service again, by accompanying doctor’s morning rounds to offer psychological and other palliative support.

But no cancer service can run on compassion alone, and as Suleiman freely, and tearfully, admits “We are all exhausted.” Almost all the staff have faced displacements, many have lost loved ones, many still have family in the north of Gaza where UNICEF recently characterised the entire population as “at imminent risk of death”. They need more international support.

Championing cancer care in a conflict situation

The failure to support the efforts of skilled and dedicated teams like the staff of Gaza’s Cancer Centre in humanitarian emergencies is an issue that has been on the radar of global cancer organisations for more than a decade, and was first covered in Cancerworld back in 2016. In conflict situations, some medical supplies get in, but not for cancer patients. Highly efficient field hospitals are set up – but not for cancer patients. Pain medications can get in – but don’t reach cancer patients.

In February 2024, spurred by experiences in Yemen, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine, Sudan, and Gaza, a WHO high-level technical meeting formally recognised for the first time the imperative for aid agencies to address the needs of the patients with non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

WHO Director-General Tedros Ghebreyesus concluded that people living with NCDs in humanitarian crises are more likely to see their condition worsen. “We must find ways to better integrate NCD care in emergency response.”

Richard Sullivan, Director of the Institute of Cancer Policy and Co-Director of the Centre for Conflict & Health Research at King’s College London, points out that this requires NCD management in emergency situations to extend beyond primary care settings. “We need to work out how we can deal with complex NCDs. That means looking at ways to move from acute humanitarian responses to more complex models and pathways.”

“We must find ways to better integrate NCD care in emergency response”

That meeting signals an important change of tone, which will hopefully lead to change on the ground, sooner rather than later. Its impact has yet to be felt within Gaza, however, where almost every one of the international medical teams that have served vital shifts over the past year come from a trauma surgery background, or occasionally gynaecology and obstetrics.

Among the rare exceptions is Mhoira Leng, an expert in palliative care who has spent much of her career helping health services in ‘fragile’ countries to build their palliative care capacity. It was Leng who, through a partnership of NGOs and universities, worked with Skaik on the programme to develop integrated palliative care capacity at the Gaza Cancer Centre. The first cohort to enrol in Gaza’s Palliative Care Diploma course – most of whom were from the Cancer Centre – were set to graduate in November 2023.

In March–April of this year, Leng was able to return to Gaza for two weeks, to see how her former students were coping, and assess what was needed to support the care of patients whose problems are not primarily related to trauma injuries or maternal and child health. She was pleased to see how effectively that training was being put to use.

At the time of her visit, Rafah was designated a humanitarian zone, and was hosting hundreds of thousands of refugees. Leng describes what she found when she visited a hospital that normally had around 60 beds, but was trying to care for 600 inpatients, with an acute shortage of many essential medical supplies, and a continuous stream of new patients.

“Some of the inpatients were sleeping outside, with drips, coming in for top-ups. If you had a cancer-related problem, you came to emergency like everybody else. So, you are in this massive queue. Every so often there was a bomb blast, and obviously the attention went to the emergency trauma injuries, quite rightly,” Leng recalls.

“When you’re under such pressure it is very hard to take on board lots of other suffering, you are just coping, just surviving” says Leng.

“I think palliative care is even more relevant when you don’t have anything else left”

She recalls watching Amjad Eleiwa, one of the doctors she had trained in palliative care, telling a family that their elderly father, who had been brought in after a seizure, had advanced lung cancer, metastasised to the brain. “The son breaking down in tears, and my lovely colleague gripping his hand so tight you can see the whiteness on his hands. Just a moment of human connection and care in the midst of this mayhem.”

“I think palliative care is even more relevant when you don’t have anything else left,” says Leng. “That sensitive compassionate clear conversation did help with some of the suffering, also giving steroids to sort out some of the swelling, and counselling to support the family. That is brilliant oncology palliative care happening in the middle of conflict.” On that same day Eleiwa got a call to say his brother-in-law had been killed in northern Gaza, while out trying to find food for the family.

When Leng reported back on her needs assessment, she did find a listening ear. At the weekly coordinating meetings run by the WHO, which include primary care services, the field hospitals, and international agencies such as the Red Cross and Médecins sans Frontières, discussions centred around the principle of forming NCD hubs that could plan and deliver complex care for patients situated in from primary care or general hospitals.

In terms of specifics to enable those hubs to function, Leng listed support for staff – both at the hub and primary and secondary referral settings – as the top priority. Then came a list of priority facilities, equipment and supplies required at primary and secondary settings as well as for the Cancer Centre itself.

In effect, those discussions were an attempt to put into practice some of the aspirations outlined at the February WHO high-level meeting.

Discussions centred around the principle of forming NCD hubs that could plan and deliver more complex care

At the point that Leng left Rafah in April, it still had two (just about) functioning government hospitals, and a primary care service. There was the beginning of NCD hubs and some non-trauma (in addition to the trauma injury) surgical care, as well as three or four field hospitals. Sadly, “these nascent chinks” were abruptly closed, says Leng, when the military operation moved in on Rafah. “Every single one of those had to close, or was destroyed, including the place where all these WHO meetings were held.”

A cancer field hospital (or two) for Gaza

So what is it that the international community should be trying to deliver?

“We must find ways to better integrate NCD care in emergency response.” Skaik, Suleiman and their colleagues could not agree more with the statement by the WHO Director General.

They look at the field hospitals supported by international agencies, where the urgent needs of trauma patients are met, at least partially, through sophisticated planning backed by logistical support, high-level equipment, and international teams to supplement Gaza’s own extensive expertise.

The Director of the Cancer Centre, Skaik, is pushing very strongly for something similar. “Currently we are looking to have some special place for cancer patients, like a field hospital, to have most of the facilities there: admission wards, a lab, an outpatient clinic, a place to prepare chemo, to give palliative care to patients.”

He says they need two such field hospitals – one in the south, and one in the north, where there is currently no cancer care provision or indeed any functional hospital at all. “Daily, we used to have 500 patients in our outpatient clinic. Daily, we had more than 140 chemo infusions. Daily, more than 70 patients being admitted. So where are those patients? Nothing is being given for them. So, we must find a place for them.”

Suleiman is just as emphatic. “We need to establish a field hospital – a complete field hospital that includes all oncology services,” she says.

Leng calls for a funded coordinated programme to support NCD services as a whole. A field hospital as a specialist hub, with all the expertise, logistics, data capacity and access to supplies makes good sense. But she also flags up the importance of support for diagnosis and care in other settings, particularly at the primary care level, working as a ‘hub and spoke’ model with a field hospital.

“There is a large gap between people being aware of [the needs of patients with NCDs] and it being part and parcel of a response”

While she welcomes the WHO’s stated commitment to supporting NCD care in conflict settings, she says more must be done to develop understanding with those who head emergency responses. “When push comes to shove, the people who run the emergency programmes in any country almost all come from the trauma environment. There is a large gap between people being aware of [the needs of patients with NCDs] and it being part and parcel of a response.”

Supporting NCD teams in emergency settings will pay off, she says. “Look after your staff, particularly in a place like Gaza where you have great staff. They know their setting, they are good at it, and they also know how to do it under conflict settings because they’ve done it for years.”

She also calls for access to diagnostic tools and referral pathways. Cancer patients cannot benefit from specialist oncology services if their disease remains undiagnosed, as is currently the case for the majority of new cancers in Gaza.

An essential medicines list is needed, both for ease of administration and to minimise patients’ need to travel, which is dangerous and very costly given extreme fuel shortage. Slow-release hormonal treatments that can be given as a single injection every three months are especially useful. Drugs for symptom control, including opiate and non-opiate pain killers, and other essential items for supported and palliative care are also on the list. Dressings for fungating wounds and mattresses to guard against pressure sores are urgently needed. Patients with open wounds can die from sepsis with the risk increased by lowered immunity due to malnutrition and unchecked skin infections, and the sheer amount of open wounds which are a breeding ground for multiresistant bacteria.

Momentum does seem to be building around including cancer and NCDs in an international humanitarian response. In August, a Manifesto for Improving Cancer Care in Conflict-Impacted Populations was launched by many leaders in global health, including the WHO Director General, and the WHO leads for NCDs and for cancer, together with signatories from St Jude’s Children’s Hospital (Memphis), the European Cancer Organisation, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, the Institute of Cancer and Crisis, in Yerevan, the King’s College London Centre for Conflict & Health Research and Institute of Cancer Policy and many more.

Its demands include: “to advance inclusive strategies and care models for cancer patients in humanitarian settings, addressing the complexity of cancer disease entities, the specific requirements for palliative care,” and that the Geneva Convention be “fully respected… in protecting medical personnel, in prohibiting attacks against medical units, and in preserving the rights of sick people, including those diagnosed with cancer”.

The question for Gaza’s cancer patients and staff is who will help them translate those demands into actual support.

“We need help. It is not a matter of begging. It is a matter of working as human beings together,” says Skaik. “Health is a right. Let us give them a right to health.”

All photos courtesy of Suha Suleiman. The images show Cancer Centre staff at their current location in part of a temporary building constructed in the grounds of the European Hospital in Khan Younis.

This is the second article in a two-part series on care for Gaza’s cancer patients. In the first part, four patients tell their stories.