It isn’t over when treatment’s over. Even if, as far as the clinician is concerned, therapy has been successful and the cancer is effectively ‘cured’, cancer patients often experience a nagging – sometimes devastating – fear that their cancer will return, months, years or even decades afterwards.

While some fear of recurrence is considered a ‘normal’ response to having cancer, evidence suggests that 40–70% of cancer survivors experience it to a level that is enduring and debilitating. Researchers have associated it with impaired quality of life, high levels of anxiety, intrusive thoughts, fatigue and being hypervigilant and hypersensitive to bodily symptoms.

But what is the actual lived experience of fear of recurrence – not just for patients but for clinicians who encounter it in their daily work? Do those working in oncology recognise its significant impact on patients, and do they feel equipped to address and respond?

A survey carried out by Cancerworld has found that cancer clinicians regularly encounter fear of cancer recurrence, but usually leave it to their patients to raise the subject. Their most common response is to refer patients on to other professionals to address the issue. However, they would like more opportunities to understand the phenomenon and deal with it better.

Thirty-eight people involved in monitoring or follow-up of cancer patients responded to our online survey. More than two-thirds of them were cancer physicians or surgeons. Six in ten said that fear of recurrence was a significant issue for at least half their patients, impacting their everyday life – sleep, mood, ability to focus, intimacy and relationships.

How big is this problem?

However, only a fifth of the respondents routinely asked patients about fear of recurrence. The majority – 22 of the 38 – said they left it up to patients to mention their fear. Eight said they selectively asked, guided mainly by their perception of whether a patient was anxious or “psychologically fragile”.

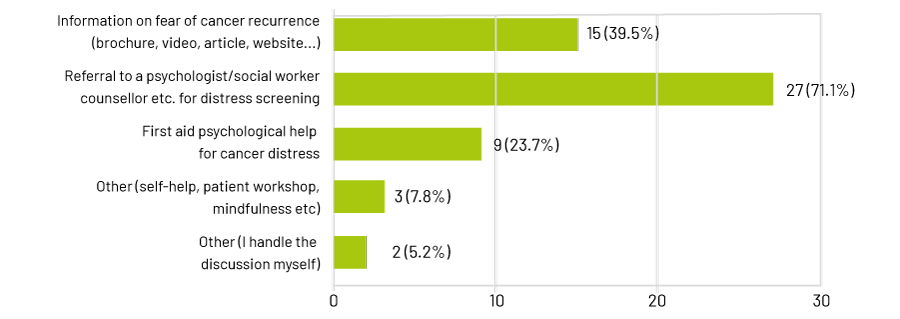

Clinicians generally describe themselves as “very confident” that they can help people manage their fears. However, their most common response to patient anxiety was referral to a psychologist, social worker or counsellor for distress screening (71%). Forty per cent said their response was to provide information via a brochure, video, article or website.

Can you help?

Interventions available?

“I openly communicate with and provide education about the support that is available to this cohort of patients from my first consultation,” said one respondent. “I provide time at our clinical visits to address fear of recurrence.”

Another said: “It is important to ensure them that they receive careful follow-up, to provide information on realistic recurrence for their malignant disease, to connect with a psychologist and share impressions over the patient’s stress.”

Their general confidence contrasts with the responses to another question. When asked whether fear of recurrence featured in any of their training or continuing education, 16 of the 38 respondents said, “not at all” and 16 said “only a little”. Nearly all respondents said they would value opportunities to understand more about fears of recurrence and how best to support patients.

Were you trained for this?

Would you value more training?

There is a clear gap here between the training clinicians feel they need, and what they actually get.

Patients want their fears recognised and understood

The findings of another new survey – this time, from the perspective of patients – also provides an impetus for action. Its findings suggest that clinicians tend to underestimate the severity of fear of recurrence among patients, and they are failing to respond effectively.

Of 183 people who responded to the patient survey, 54.1% said they were “very scared” of a cancer recurrence or progression. For more 40%, this fear had persisted for five years or more. But only 12% thought that medical professionals understood their fear of recurrence well. Mental health professionals scored particularly poorly, with less than 9% of respondents thinking they had a good understanding.

The patient survey was originated and co-ordinated by UK counselling psychologist Cordelia Galgut, who has written extensively about the long-term physical and psychological effects of having cancer. She started her fear of recurrence survey after a disturbing experience when attending a breast screening clinic.

“I’d had many messages from men and women in response to my books and blogs, telling me how desperate and undermined they have felt while struggling with fear of recurrence, even to the point of feeling suicidal,” she said. “People have said that just reading some recognition that it is normal to feel terrified has pulled them back from the brink.

“And then I went for my annual mammogram. I still have it, 18 years after first being treated for breast cancer – and I find they get more terrifying than ever. Perhaps I feel I’ve got more to lose. It’s not just a fear of dying. There’s also the dread of having more treatment and suffering.

“So at the mammogram clinic, people normally just sit there in the waiting room, often in terror, praying they’ll get through it okay. Opposite me was a woman who was understandably beside herself. She was saying that she really couldn’t bear it, and that this was hell for her. So I told her I knew how she was feeling, and talked to her and then asked her if she would like a hug. She said yes, and she seemed happy with that.”

“There was something about the combination of this experience and the messages I’d received that made me want to do something”

“I went in for my mammograph, and everything was fine for me. Then she went in after me, so I went off to find the breast cancer nurse, because I thought she should know that the woman was understandably in a bit of a state. The nurse just said: ‘Oh yes, I know her. Don’t worry: she’s like this every year.’ And she seemed so judgemental and dismissive about what is a normal reaction of a woman living with fear.

“There was something about the combination of this experience and the messages I’d received that made me want to do something. This felt really important.”

One of the aims was to add a patient perspective to the sketchy body of research about fear of recurrence. The current evidence suggests that check-ups, monitoring, treatment anniversaries and seeing others develop cancer or experience progression can all trigger or exacerbate these fears. There’s little evidence that it is associated more with some types of cancers than others, but some studies have suggested that fear of recurrence is more commonly experienced by women, younger people, people of lower educational achievement and people who are employed (Psycho‐Oncology 2022, 31:879–892; J Cancer Surviv 2013, 7:300–322).

When it comes to how clinicians should respond, the research generally recommends screening with validated questionnaires and then psycho-social interventions. But exactly how these should be applied is unresolved. As a new educational paper on fear of recurrence, for the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), concludes: “A range of studies are evaluating interventions for FCR [fear of recurrence] and associated symptoms of distress and depression in patients with cancer. As results are reported, we anticipate greater clarity on personalized evidence-based interventions for FCR.” The value of promoting discussion, reassurance, education, cognitive behaviour therapy, mindfulness, and various online and app-based self-management programmes are all being researched.

Local contexts

But talking to individuals who responded to our survey, it is clear that clinicians face practical and cultural issues which mean that finding effective ‘interventions’ may be complex, and vary from country to country.

A radiotherapist from Bucharest, Romania, who prefers to remain anonymous, says that cultural factors may mean that patients’ response to cancer’s long-term consequences in her country may differ from other parts of Europe.

“In my country, some patients think that if you have cancer you are dead,” she says. “They are always afraid. For some, this may settle down after treatment, but others are very scared. If they have a headache or a pain, they think it is cancer coming back.”

She thinks this may be related to a historic attitude in Romanian patients: some don’t want to know about their illness or take control, they just want doctors to do what they think best.

“I also worked in Switzerland, and it is totally different there. The patients are more sure of themselves, know exactly what disease they have and what treatments and medicines are available. In Romania, if you ask patients, they don’t know. Very often patients say: ‘I don’t understand. Do what you know, do what is best for me.’

“I think that very often, when radiotherapy is over, patients feel they are abandoned. I remember one patient who had a treatment: she went home, and after two weeks her daughter called me and told me she thought her mother was dying. ‘But your mother is okay,’ I told her. She said her mother stayed in bed all the time and wouldn’t eat or drink. I asked her to put her mother on the phone, and I told her: ‘You are okay, there’s nothing wrong.’ And she got out of bed, and from that day she was fine. At the follow-up, she told me that over the course of treatment I had become like her mother, and felt that I had abandoned her, and that was why she was so afraid.”

Another difference between countries and regions may be the availability of referral infrastructure: whether psycho-oncologists and other support services are easily available.

But one respondent to our survey raised the question of whether screening and referral was the main priority for cancer clinicians when faced with fear of recurrence.

End of treatment conversations are key

Stefan Bielack was until recently head of the Department of Paediatric Oncology, Haematology and Immunology at the Stuttgart Cancer Centre in Germany. As a paediatric haemato-oncologist, he is well aware that fear of recurrence needs to be addressed in those who have cancer early in life. All too easily it could have a crippling influence on what should be many decades of good quality life after treatment. So access to psychologists – for both parents and their families – has to be an intrinsic part of support.

But it is not everything, says Bielack. It is the conversations that all patients have with their oncologists and other clinicians at the end of their treatment that are key.

“As a specialist paediatric oncology centre, we’re in the privileged situation of having psychologists for every level of patient. Unfortunately, even here, they are often busy. It’s routine to involve the psychologist at the end of treatment talk, but it doesn’t always work out.

“The talk at the end of treatment is very important. During chemotherapy, the worries of patients and families are sort of put somewhere behind – they’re busy with the practicalities of how to get to hospital, what to do if the child has a fever and so on. There’s always something going on. The fear of the cancer itself and the fear of recurrence is stored away somewhere.

“You feel that your child is a sitting duck. It is extremely important for the patient and family to know that they are not alone with this”

“However, when you near the end of treatment, you suddenly get to feel that you or your child is like a sitting duck. It’s like someone is taking aim and there’s nothing you can do to protect yourself. So at the end of treatment, I think it is extremely important for the patient and family to know that they are not alone with this – that this is normal, and everybody goes through it.”

Bielack makes a point of addressing this fear. “I say: ‘I know that you’re happy that treatment is over, but your worries are not less than before.’ And then I go over the follow-up schedule and try to be positive about the future – to try to show the route back to normal life.”

It is then important to raise the subject of fear of recurrence at every follow-up meeting, adds Bielack, particularly as this is a prime time when anxieties are likely to peak. “When patients are at home, they are busy with school or work, and they get less concerned. But when they come back for their check-ups everything resurfaces. And again, I feel that it helps them to say: ‘I know this is a panicky situation, that this is terrible for you.’”

Bielack’s point is that the most important thing that clinicians can do to minimise fear of recurrence is to normalise it, and that this is something that can be done with all cancer patients, not just in paediatrics. “Once patients hear that their fears are normal, it’s easier for them to live with it and put it into perspective.”

This is exactly the point that Galgut makes, concluding on the patient responses to her survey. For all the research on interventions, referral needs and screening procedures, what’s actually required is something very simple.

“Screening for anxiety and involving psycho-oncologists is fine, but it’s a medicalised perspective. Fear of recurrence is entirely normal”

“The whole idea of screening patients for anxiety and involving psycho-oncologists is fine, but it’s an entirely medicalised perspective. My point is that fear of recurrence is not a mental health problem. It’s entirely normal. But as soon as you say an assessment is necessary, and it’s something that can be diagnosed, you’re pathologising it.

“I want clinicians to see what they are doing wrong, and what they can do differently to support patients. Perhaps the single most useful thing you can do is validate how they are feeling. The experiences of the people who provided personal statements in the survey demonstrate clearly that failure to openly recognise fear of recurrence has a very negative impact on people’s lives.”

The main requirement then, seems to be on individual health professionals as much as on health systems. It’s the simple requirement not to stigmatise – as happened to the woman in the breast screening clinic – but to inform, empathise and normalise.

One of the respondents to our clinicians’ survey put it best, when asked about the lessons they had learned about fear of recurrence from their own clinical experience.

“A lot of clients appreciate simple validation of what they are experiencing, and then the common humanity that they can experience via a self-help group or opportunistic discussions with other patients. Being there for them without judgement seems to really help.”

Thanks, and next steps

We’d like to thank everyone who took the time to respond to our survey and share their experiences and tips in relation to this challenging topic. On reading the responses, one significant point that stood out for us was that fear of dying, and of death, is universal and it can be hard to distance one’s own feelings when acknowledging the fears of patients. This is a topic we think might be interesting to explore in a future Cancerworld survey.

We’d like to thank everyone who took the time to respond to our survey and share their experiences and tips in relation to this challenging topic. On reading the responses, one significant point that stood out for us was that fear of dying, and of death, is universal and it can be hard to distance one’s own feelings when acknowledging the fears of patients. This is a topic we think might be interesting to explore in a future Cancerworld survey.