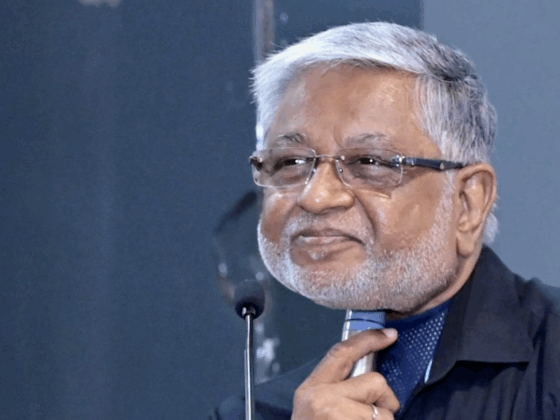

Trying to improve the survival chances for children with cancer is the day-to-day work of Kidzcan in Zimbabwe. Support and advocacy groups in Western countries supplement the work of their health services. By and large, we are those services. We have valued partners and supporters locally and globally, but from awareness raising and training primary healthcare workers to recognise suspicious symptoms, to accessing diagnostic pathology and imaging, providing treatment by paediatric oncologists and accessing cancer drugs, supporting the psychosocial, financial and nutritional needs of patients and their families – we are the ones who do that.

We know how to improve our survival rates, and it’s not as impossible as it may sound. What we need is more joined-up coordinated support at a global health level, and more buy-in from our government. Securing the former would help in securing the latter.

This is our reality

Let me give you an idea of the problems we face. I’ll start with access to drugs, because this shows why we need to be part of something much bigger. We used to purchase medication through the government pharmacy. But, due to the foreign currency crisis, from 2017 they stopped importing childhood cancer medicines. We had to buy it in from the private sector, but the cost was unsustainable. We then asked for a licence and permission to import what we needed direct from India. But that meant we had to overcome big logistical and bureaucratic hurdles – temperature-controlled transportation and storage, securing a ‘section 75’ waiver for permission to import chemotherapy drugs on the grounds that they are unavailable in the country and not manufactured, getting the government to waive the import duty.

We reached out to the National AIDS Council for assistance – they have secure funding derived from a 3% corporation tax – and they generously agreed to cover our medicine bills for the time being. (Kaposi sarcoma, associated with AIDS infection, used to be among the most common childhood cancers, as a result of babies being born with AIDS transmitted to them via maternal infection.) The National AIDS Council currently also pay for diagnostic imaging and pathology, which has to be done within the private sector because capacity in the public system is so run down.

“Our oncologists have to adapt the standard of care according to what is available to us”

Even so we struggle with access to many key drugs, including vincristine and asparaginase. It leaves our oncologists constantly having to adapt the standard of care in favour of protocols based on what we have available to us. Access to morphine is currently another very stressful issue, with supplies well below what the country needs.

It’s a major undertaking for a small foundation, and we end up paying a higher price because, unlike the government, we don’t have the resources to buy in bulk. We’ve had talks with pharmaceutical companies and with organisations such as the Clinton Health Access Initiative – which has a programme for accessing drugs at a discount – but again they require us to buy a minimum quantity in one go, which we cannot do. We’ve had to ‘think outside the house’, and we are now partnering with a local distributor, which imports on our behalf in large quantities, and we draw down as we go along throughout the year. We’re also in touch with the US-based National Children’s Cancer Society, which collect drugs nearing the end of their shelf life and make them available to foundations like ours, particularly to address our urgent morphine needs.

This is not huge amounts of money we are talking about. Childhood cancers are rare and rely largely on drugs that have been off patent for decades. While there is help out there, it is fragmented and uncertain and doesn’t always fit our needs. How hard would it be, we ask, to bring together all the different agencies and pharmaceutical companies and governments and global health bodies behind a single global fund that could streamline access to essential drugs for patients in countries that need help, as we do?

Closing the gap in early detection

While better access to treatments is essential in helping close the 25%–85% survival gap, the biggest impact we could make would be to improve our rates of early diagnosis. In Zimbabwe 60% of our children present late, and many are never diagnosed at all. But with the right support, we could do a lot better. We proved that, with a huge awareness campaign we conducted with the support of UNICEF back in 2018.

Zimbabwe has a functioning primary care infrastructure, though it is somewhat patchy in many rural areas. It is reasonably effective in delivering programmes for infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis. It has an important role in promoting child health, including delivering childhood vaccination programmes. Every child has a ‘Road to health’ card, which parents are given at their birth, which they present at local primary healthcare clinics, and is used to record vaccination status but also to monitor children for normal development and growth.

Our strategy was to focus on these primary care clinics, and share with the nurses knowledge and information on the childhood cancers they were most likely to come across. We partnered with our surgeons for educating about Wilms tumours, and with our eye specialists for retinoblastoma, and we taught the nurses the basic signs and symptoms. Each clinic was given a referral book. Our message was: Where you suspect it, just refer to the cancer centre. We said: even if you refer 100 kids, and one kid is diagnosed – that may look like 1% to you, but it is 100% to that child and their family.

We taught them how to use a torch to check for signs of retinoblastoma, and we gave a torch to every clinic. And we brought children with Wilms tumour to the clinics, some at a pre-operative stage and some post-operative, so the nurses could touch and feel for themselves what that lump feels like. And we got the nurses to incorporate some of that symptom awareness into their routine ante-natal classes, to share the information with the mothers.

We covered 51 primary health clinics in total – every clinic across the capital city Harare and our second largest city Chitungwiza. During that three month campaign, 61 children with suspicious symptoms were referred for further diagnostic tests.

We also started to engage with the traditional healers, who are sometimes the first place parents go for help when they have concerns about the health of their child. In 2019 we were fortunate to be awarded a grant by the Tearfund Australia, which enabled us to do a national campaign to raise awareness and educate health workers and traditional healers on childhood cancers, which we found to be very effective. Sadly that work was disrupted by the Covid pandemic.

“Systems are in place for malaria and tuberculosis. We need that extended to childhood cancers”

We’ve shown that training and educating healthcare workers and those responsible for child and maternal health does have an impact. But that’s not a responsibility a small foundation like ours can shoulder year after year. Systems and processes are in place for malaria and tuberculosis and other diseases. We need that extended to childhood cancers. The current nursing curriculum has nothing on childhood cancers, social workers learn nothing about childhood cancers. Medical doctors get no training in childhood cancers, or if they are asked to do a childhood cancers module, it is not examinable, they don’t take it seriously. Doctors who choose to come to Kidzcan for a three month rotation get the benefit of two weeks expert training, thanks only to regular visits by paediatric oncologists from the world leading St Jude’s Children’s Hospital in the US.

We also focus heavily on supporting families to stick to the full treatment regime, which can be hugely burdensome. For many it means losing income they can ill afford to lose. A major project for us has been building a “half-way-home” accommodation – our Rainbow Children’s Village – to enable disadvantaged children living far away, with no relatives or friends in Harare, to spend time recovering from their chemotherapy treatment and building their strength before the journey home. On February 9th this year we opened our doors to the first three guests. It felt like a life-changing moment for children with cancer in Zimbabwe – an emotional day.

We currently have three paediatric oncologists at Kidzcan, all of them trained in top hospitals in South Africa, in first-world settings. Though they could work anywhere, they want to work here… but it only makes sense if they can make an impact. At Kidzcan we are doing everything we can to create the conditions to maximise that impact – earlier diagnosis, better access to treatments, helping families stay with the treatment regime. But we are a small foundation heavily reliant on volunteers. It takes more than us.

Hopeful signs

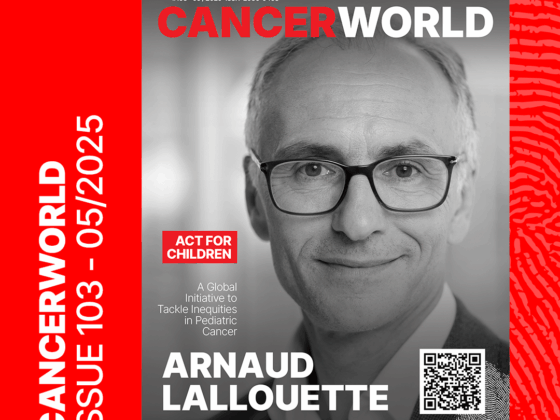

We need immediate help to establish secure access to diagnostics and treatment. More important, for the long term, is help convincing our government to build childhood cancer training and services into the health service at every level. We have high hopes that the Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer, which was launched in 2018 by the World Health Organization in collaboration with St Jude’s Hospital, will help make that happen. We were delighted that in 2022 Zimbabwe signed up to be a focus country for the Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer, which formally signals government support for collaborating to raise survival rates from the current levels of around 20% up to 60% by 2030.

We hope that support will be more than words. They announced a fund for childhood cancer. A year on, that has yet to materialise. Healthcare for all children up to the age of five is supposed to be free in Zimbabwe. That is not happening. The government must live up to what it signed up to. We hope too they will take advantage of the help offered through the Global Initiative for capacity building, planning and implementation of services.

We hope too that Zimbabwe will be chosen as one of the 12 countries that St Jude’s has committed to support with access to drugs, for a period of six years. For us that would make a huge difference. Imagine us no longer having to buy our own drugs. That would change the way we look after our children. We can put that extra funding into diagnostics or to awareness. If St Jude came on board, and the government came on board to take care of the facilities and the tools in the hospital, we can then look after the wellbeing of the child and raise more awareness throughout the country.

That way we can get more children presenting early and the tools and facilities will be there.

That is my dream and my hope.

Let’s close this equity gap of haves and have nots. Lets be the first initiative where we will come together and make sure the world is equal and we all reach this target. It’s a global WHO initiative, and we believe the WHO can carry more influence than we do to convince the government to really come on board with this.

Despite all the challenges and gaps, we continue to fight for childhood cancer in Zimbabwe. We’ve shown that, with help from others, we can make lives better. How much more could we achieve with more structured and sustained backing from our government and global health bodies? Anyone can dream, but how many live their dreams? We do.