“One must imagine Sisyphus happy”

Albert Camus

Why me? This is probably the present-day question of every patient with cancer!

One of the consequences of our chaotic reality is cancer, which belongs to that class of diseases that impacts the mental health of the patient and their family; life after the oncological diagnosis will never be the same for any human being.

The first and most important aspect is that cancer influences the emotions of every patient, as well as the understanding in the eyes of every human being. Therefore, the common perception is that:

• cancer is fear – the word itself stirs up an imminent danger

• cancer is sadness – the word itself suggests the threat of loss

• cancer is anger – the word itself can bring to mind the thought of a limited life

In this regard, Psycho-Oncology is one of the first domains of health and clinical psychology that has been developed at the borderline of medicine and psychology. Hence, Psycho-oncology is gaining subspecialty status by currently bringing a set of clinical skills in counselling, behavioural and social interventions in oncology, by providing training programs that teach basic knowledge and skills in the field, and by creating a body of academic research concerning relevant clinical aspects in the care of cancer patients.

But, despite the progress in medicine and technology, cancer remains a relentless disease. The news that a person has cancer is terrible not only for the patient but also for the family members, and it can bring unexpected changes in the relationships with and between them. After such a diagnosis, there will be changes in responsibilities and priorities in any family life, and during treatment and recovery, there will be many other challenges.

HOPE to deliver quality results in minimal time

Regarding the field of psycho-oncology, the last IPOS congress theme from Maastricht 2024: Cancer in Context, was meant to illustrate an integrative approach regarding the oncological disease. Despite the optimism within panel discussions, there remains a practical and academic gap among psycho-oncological specialists, with a focus on Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) or the lack of trust in psychological counselling in the former Eastern European countries.

While in high-income countries, Artificial Intelligence and E-Health are the current topics of research, some other countries face food insecurity, stigma and inequity in cancer care, themes that should have been on the agenda, too. Moreover, research means huge investments (especially in the oncology field), though there are nations where primary care still can’t be achieved.

Unfortunately, we are living in the paradox of oncology: the development of medical sciences should have led to further discoveries in the field of cancer psychology, as well as the development of new methods of dealing with fundamental psychological problems and traumas. However, medicine and psychology seem to have gone in different directions.

This paradox was the starting point of my interview series Beyond the Cancer Diagnosis: in order to figure out how deep this gap is and if we can approach oncological disease from a psycho-social dimension. It was not an easy task, but the potential was promising.

I still remember my first interview with Patricia Moreno, clinical psychologist and Gilberto de Lima Lopes Junior, Associate Director for Global Oncology at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, shortly after the Princess of Wales’s diagnosis, when the world was both shocked and curious about the subsequent trajectory of the disease. It was for the first time that during an interview with a clinical psychologist and an oncologist, we approached terms like: coping with cancer, family support and hope over fear.

Thus, progressively, researchers, professionals, CEOs and patients have accepted this challenge to share knowledge and personal opinions on pressing issues in the oncology field, all from a psychosocial perspective.

Consequently, I have learned that we are all committed to the same aim: to improve the Quality of Life of every cancer patient with HOPE as the main trigger in searching for the meaning of life in this new reality or, as Harriet Cabelly, grief therapist and cancer survivor, pointed out very nice during our interview: I don’t want to come back empty-handed from hell!

What I learned during this year

Each person constantly contributes to their own state of health. The word contributes indicates the vital role each person plays in creating their own health. Most of us assume that healing is something that is done from the outside and if we have a medical problem, our responsibility is simply to go to a doctor. This is true to a certain extent, but it is only a part of the truth. We all contribute to our health through our ideas, our feelings and our attitude towards life in general and illness especially.

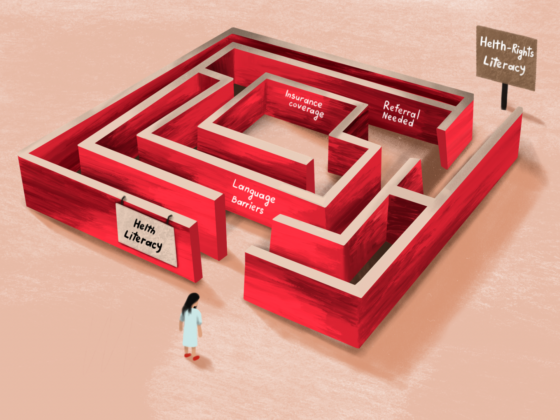

The problem arises when the resources regarding the situation (cancer treatment) far exceed those available to the person, and it is one of the answers to the question of why the majority of the world population doesn’t take part in screening campaigns. In this regard, Judy Medeiros Fitzgerald, an active advocate for breast cancer prevention and founder of the Sisters4Prevention project, explained that this phenomenon is based on the following reasons: the screening indeed is free of charge, but if the result is positive, everything is paid since cancer isn’t a low-priced disease. Therefore, the population avoids participating in screening campaigns because they can’t afford an eventual diagnosis.

This aspect is particularly important for the reason that we enter the field of self-stigmatization. Stigma became a topic of intense debate due to the lack of psycho-education. Concerning this issue, Foluke Sarimiye, Clinical Lecturer in Radiation and Clinical Oncology at the University of Ibadan and University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria, argued that children in Nigeria do not touch another one having cancer because they believe that cancer is a contagious disease. Unfortunately, Nigeria is not the only country where this mentality prevails.

As for the psycho-education in the field of oncology, Marianne Arab, Provincial Manager of Psychosocial Oncology, Palliative and Spiritual Care with the Nova Scotia Cancer Care Program, argued that even though executive education is important and school curricula are improving gradually, “we have a lot of work to do in educating the general public, and in educating ourselves, and then I think we’ll have made some inroads in how do we talk to kids about it”.

At this time, Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA) are the most vulnerable category of cancer patients. Lauren Fryzel, the Senior Manager of Patient and Community Outreach for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS), explain this vulnerability in common terms, because “patients are getting diagnosed too late, because both the patient themselves are like, oh, it can’t be cancer, I’m too young for that. And making assumptions about their health or being afraid to go to the doctor because they don’t want to know what’s going on. And the other side is the provider side of it can’t be cancer, they’re too young for that, right?”

Moreover, AYA faces multiple barriers to achieving access and equity in cancer care. In this connection, Betty Roggenkamp, a recognized specialist in cancer care quality improvement, points out the main barriers as follows:

1. Access to care that recognizes their unique life stage and needs.

2. Financial burden, as cancer-related costs can impact their short and long-term financial stability for decades.

3. Late and long-term effects – physical, mental, financial, and oncologically that follow them well beyond treatment.

Thus, as professionals, we have to deliver transparent and sincere information about the patient’s situation. The fact that he/she is young is not an excuse and doesn’t mean that they will not find out what is really happening to them. There is a lot of information on social media and Google that can be easily accessed, but the problem is that there is also a lot of misinformation and, especially, disinformation, which should make us vigilant.

Presently, there are three issues that are most disputed among psycho-oncologists and not only:

1. Denial of cancer diagnosis – broadly speaking, denial as a coping strategy varies considerably: ambivalence and ambiguity are often used in the service of denial. Nevertheless, it appears that as long as denial does not affect the patient’s adherence to medical instructions, it has great potential to improve their quality of life. Mila Ogalla Toledo, a young colorectal cancer survivor and AYA (Adolescents and Young Adults) cancer patients advocate, expresses this by sharing her own denial experience: “It is not easy, and I think it changes. Like, I’ve been maybe better in the past, and I might get the worst anxiety of my life next year. I do not think that you can control that or manage that. But if you can remind or do your best to remember that it’s okay to have those moments, and it’s okay that every single time that you’re going to get an appointment or you’re going to do a test, you might feel different about them.”

2. Positive attitude/thinking – keeping a positive attitude does not guarantee a better chance of survival among cancer patients, since there is no scientific proof with regard to this issue. Moreover, some researchers talk about the contemporary tyranny of positive thinking, which sometimes victimizes people. Definitely, defining what constitutes a truly positive attitude is a complex issue. But, being “too positive” all the time can lead to denial, which can prevent you from getting the medical information and treatment you need. A common approach is shared by Prof. Cristian Ochoa, Clinical Psychologist in Psycho-oncology Service and Chief of the Digital Health Program at the Catalan Institute of Oncology; in his view, “cancer patients don’t need to be positive. Positiveness is not a mandatory enemy that people have to maintain in such an adverse situation. Positive is sometimes the way that we explain in a popular way how to find our best version, how we can live, fully live in this situation, but it’s not mandatory, it’s not a kind of tyranny of the patients. It’s a kind of natural response.”

3. Too much HOPE is a false hope – there are a lot of debates about what hope really is: an emotion, a strategy, a mirage, etc. During my interview with Taryn Greene, PhD, Director of Research at Boulder Crest Foundation and the home of Posttraumatic Growth (PTG), she defined the nuances of hope as follows: “I imagine the cancer area of work is a place where that candle, that flame of hope is especially important … What I like to say about hope is that sometimes you know that people lose hope, that is a piece that happens in traumatic situations and losing a focus on hope can feel like you’ve lost it and that you’re never going to find it again… Hope has been defined in the psychological literature as more of a kind of goal-centred concept where folks have identified goals and are able to kind of identify pathways of getting there and are able to access motivation to move towards those goals again we’re talking about looking forward.”

To sum up, when faced with negative daily events, people may choose to suppress negative emotions or express them. While there can be benefits to suppressing or avoiding these, there can also be downsides. During this year I have learned a lot and faced many challenges walking on this path but the greatest achievement is the words of Dr. Alberto Costa, CEO of the European School of Oncology (ESO) which always come into my mind: you can’t be a good (psycho)oncologist if you don’t know how to handle the why me question!