Arjun K. Ghosh on Building Cardio-Oncology From Scratch and Why the Goal Is Almost Never to Stop Cancer Treatment

Professor Arjun K. Ghosh

A cappuccino sits within reach as Professor Arjun K. Ghosh talks—a coffee that keeps pace with a day split between heart failure, imaging, and the fast-evolving world of modern oncology. On screen, his mug carries the Arsenal crest, a quiet nod to North London roots and a family ritual of match days and season tickets. “I grew up near the stadium,” he says. “My parents’ house at the end of the street was the old Highbury Stadium.” He still remembers the day Arsenal won the league and “everyone was dancing in the street.”

Ghosh is a consultant cardiologist at Barts Heart Centre and University College London, and the first consultant in the UK specifically appointed to cardio-oncology. His job—and his project—has been to build services that protect the hearts of people with cancer while keeping the central purpose of cancer medicine in view: giving patients the best possible chance of cure and survival.

“I never once felt during the journey that I made the wrong decision,” he says. It is a simple sentence, but it carries years of risk-taking, resistance, and the slow work of changing how medicine thinks.

When Cardio-Oncology “Found” Him

Ghosh’s entry into cardio-oncology began near the end of cardiology training, when his clinical interests were already forming: heart failure and cardiac imaging. Then came a conference talk that reframed the landscape.

“I heard a talk at a conference on cardio-oncology,” he recalls. “This is a new area, and we’re bringing cardiology and cancer together.”

At the time, cardio-oncology looked different from what it is today. “From the cardiac side, most patients had heart failure,” he says. “That has changed dramatically now, but back then, it was really just heart failure.” Imaging was fundamental. “The imaging was integral to diagnosing these patients and treating these patients.”

The fit was obvious. “Given my background in imaging and heart failure, I really felt that this was a new area in cardiology that could combine both my skill sets.”

Then he gives a more personal reason—one that many clinicians might recognise. “I am probably the kind of person who gets bored easily,” he says, smiling. “The fact that this was new, interesting, and exciting. I felt it was unlikely that any two days would be the same. Everything was unknown.”

Choosing the Unmade Road

Cardio-oncology was not an established speciality in the UK when Ghosh entered it. That uncertainty and the opportunity within it were part of the attraction.

“I didn’t want to go down an established route,” he says. “I wanted to do something different.”

His desire to diverge goes back to his earliest identity in medicine. “Many people in my family are doctors,” he says. “Grandparents on both sides, aunts, uncles, cousins, they’re all doctors.” He could have chosen a traditional path and built a conventional career. But he wanted something else.

“I didn’t want to just be seeing lots of patients and being very successful in that,” he says. “I wanted to try and make a difference, do something more meaningful on a larger scale.”

He is careful here. “Of course, seeing patients is extremely rewarding,” he adds. “But I wanted to move the field forward.”

Clinically, he had seen the gap. “All cardiologists see cancer patients. That’s normal,” he says. “However, they weren’t being treated necessarily in an optimal way.” And sometimes cancer itself became the reason to abandon cardiovascular care. “If they had cancer, people would say, ‘Your prognosis is X months; there’s no point giving you cardiac treatment.’ There were a lot of misconceptions.”

The choice to pursue something new also carried risk. “It was a high-risk approach,” he admits, “but also a potentially high-reward approach.” He remembers senior doctors advising him to keep a safety net. “This is new. It may not work out. After a few years, this may all fade away.”

He listened and declined to step back. “You can respectfully disagree,” he says. “Thank you for the advice, but I think this is something I’m interested in.” And then the sentence that could double as a rule for any disruptive career in medicine: “If you’re going into a high-risk situation, you need to have a passion for what you’re doing, because there will be lots of ups, but there will be lots of downs as well.”

A Clinic With One Patient, and Then None

Innovation often begins in awkward silence.

“I still remember when we set up the clinic,” Ghosh says. “The first clinic, it was just me, and there was one patient.” The next one was worse. “The next clinic, it was just me with zero patients.”

It is the kind of early failure that forces you to decide whether a new idea is a belief or a fantasy. He chose belief. “You have to believe in the project,” he says. “You have to really be dedicated. It is a lot of hard work.”

The growth took years, but it came. “Now we have two clinics a week at Barts Heart Centre. We have three clinics a week at UCLH,” he says. “We now have five clinics a week, up from a point when there were zero patients.”

He doesn’t frame this as a victory. He frames it as what happens when you persist long enough for the system to catch up. “At the beginning, it was extremely challenging,” he says. “But the rewards are there at the end.”

Being “The First” and The Responsibility of It

Ghosh was the first consultant in the UK to be specifically appointed to the field of cardio-oncology. Even naming the field could provoke skepticism.

“Cardio-oncology has only been around for three years, maybe four years,” he says. “And I was the first appointed specifically in cardio-oncology. That was my job.” He remembers how colleagues reacted. “People thought this was going to be a fad.” The questions came fast: “What is cardio-oncology? You got a job in that? Is that a thing?”

But he was watching oncology evolve, and he was certain the cardiac problem would not disappear. “Every day there’s a new drug that comes out,” he says. “The drugs are amazing from the cancer perspective, and they’ve massively changed outcomes for cancer patients. Unfortunately, many of these do have a toxic cardiac profile.” So, he says, “I didn’t think cardio-oncology was going to disappear. The problem may change, but there would still be patients who would have these kinds of cardiac issues.”

He never regretted it. “I never once felt that I made the wrong decision.”

What the role demanded, he says, was not only clinical delivery, but field-building: “writing guidelines” and “producing protocols” to define best practice. Yet the heavier responsibility, in his view, was toward those who come next.

“I feel I have a very big responsibility to the next generation,” he says, “to trainees who want to do cardio-oncology.” He helped write the cardio-oncology section of the UK cardiology curriculum. “Now, all trainees in the UK have to do cardio-oncology as part of their core cardiology training,” he says. “And if trainees specialise in heart failure, they also have to do cardio-oncology.”

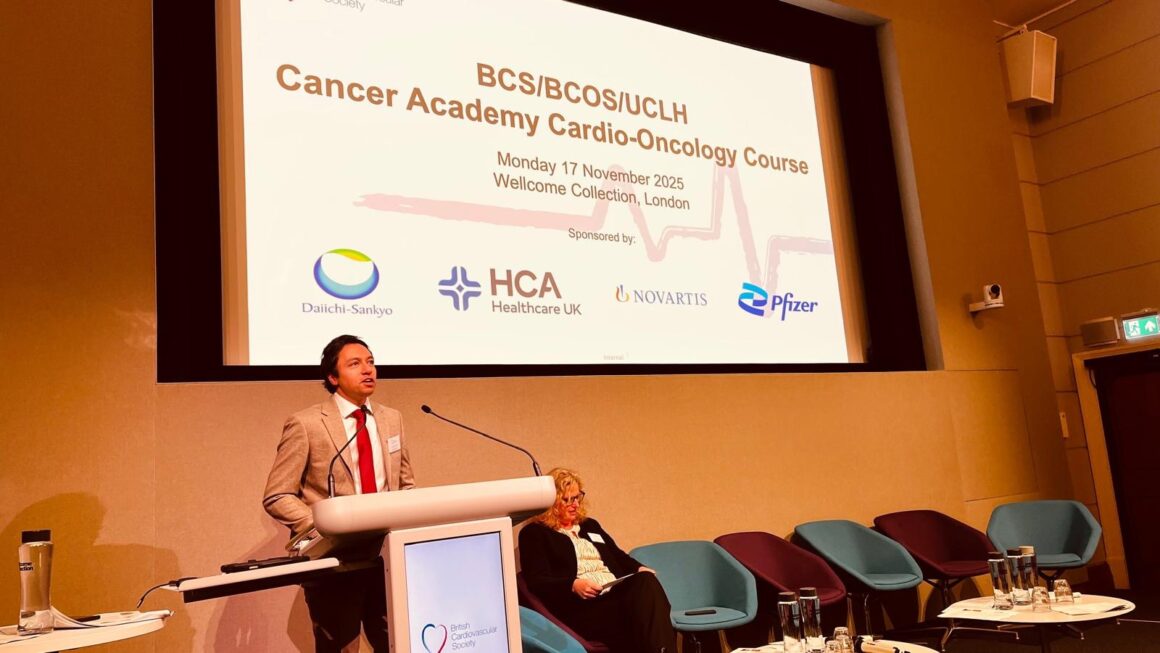

33rd Annual Scientific Congress, Hong Kong College of Cardiology, 6-8 June, 2025

He also refuses a cardiology-only model. “Cardio-oncology is a combination of cardiology and oncology,” he says. “So, I must not just train cardiology trainees, but also oncology trainees.” He describes one current example with pride: “I have an oncology trainee. He attends my clinic, attends the MDT meeting, and has passed his cardio-oncology exam. He’s a certified cardio-oncologist.”

“It’s a privileged position to be the first,” he adds, “but not the last.”

Teaching as Legacy, and Exporting a Service Model

Ghosh speaks about teaching not as an obligation, but as an identity. “The word doctor comes from teacher,” he says. He mentions his own formal training in education. “I’ve got a master’s in medical education.”

What seems to energise him most is the global spread of the work. “In my clinic, I always have some visiting fellow,” he says. “We’ve had visiting fellows from South America, from Mexico, from all over Europe, from Asia, from India, from China, from Singapore, from Bahrain, from the Middle East, and from Australia.”

Professor Arjun K. Ghosh with his fellows and colleagues

And the goal is not a certificate. It is replication. “The aim of the fellowship is that when they go back home, they set up their own cardio-oncology services,” he says. Then he lists the places where it has already happened: “Sydney, Melbourne, Singapore, Mumbai, Bogota, Mexico City, Portugal, Madrid, Salamanca, many places all over the world.”

This, he implies, is what turns a new area into infrastructure: “spread awareness” through “trainees all over the globe.”

The Speed Mismatch and a Guiding Rule

Cancer care moves at extraordinary speed. Cardiology is trained for caution. How do you reconcile them?

Ghosh is honest about limits. “We cannot keep up with the rapid changes on the cancer side because it’s too fast,” he says. And cardio-oncology isn’t one disease site; it is all of them. “We deal with breast cancer, renal cancer, haematological cancers, radiation-induced problems,” he says. “It’s next to impossible to keep on top of everything.”

So, he uses a guiding rule that is deliberately broad, designed for a world where new therapies arrive faster than comfort. “Any cancer treatment can cause any cardiac problem,” he says. “Some problems are more common, and some are less common.”

That rule, he explains, prevents complacency. “When a new treatment comes, we should not be saying, ‘This is new, this cannot be the cause,’” he says. Instead, cardio-oncology has to stay alert to signals and then work with oncology to interpret them without panic.

He points to CAR-T therapy as a recent example. “CAR-T was still trial therapy just before COVID, and now it’s a normal NHS therapy,” he says. Because UCLH was one of the trial centres, “we were involved from a cardiac point of view at the very beginning.”

The advantage of being embedded in trial centres is proximity to the frontier. “We are involved at the beginning,” he says, “so we are in touch with the latest advances.”

Trust is the Missing Ingredient in Collaboration

When asked about the biggest barrier to collaboration between cardiologists and oncologists, Ghosh answers quickly: misunderstanding.

“The biggest issue was oncologists thinking we were going to stop the treatment,” he says. “We were going to interfere with the cancer treatment.”

Then he states the field’s purpose in a sentence that feels like a manifesto: “The whole point of cardio-oncology is never to stop the cancer treatment unless it’s an extreme situation,” he says. “The whole aim is to get the cancer patient to complete the optimal treatment with support from our side.”

Before cardio-oncology, the response to toxicity could be abrupt. “If there was cardiac toxicity, the oncologist would just stop the treatment,” he says, moving patients onto “second line, third line, less effective treatment.” Cardio-oncology exists to prevent that: “keep the patient on the primary, most optimal treatment with our support.”

He has seen the same suspicion in other countries. “I’ve helped colleagues all around the world set up cardio-oncology services,” he says, “and I’ve never once seen anywhere where the oncologists have said, ‘This is great, please start the service.’ Often, there is suspicion and hesitation. Very quickly, it changes the other way.”

Context matters. In India, he notes, “it’s the oncologists more than the cardiologists who are driving cardio-oncology,” and the problem is the opposite: “to find a cardiologist who is interested.” Incentives shape interest. “If you work in a healthcare system incentivised by procedures, cardio-oncology doesn’t have procedures for cardiologists,” he says. “So, they may not be so interested.”

But he returns to what he has learned from experience: “If you keep at it and provide a good service, most people will understand there’s a benefit.”

Not “Side Effects”, the Entire Cancer Journey

Cardio-oncology is often framed as the management of side effects. Ghosh calls that outdated.

“That’s an old-fashioned view,” he says. Cardio-oncology, in his telling, covers the whole timeline. “We assess patients before cancer treatment,” he says. “At that point, there are no side effects yet.” They stratify risk: “low risk, medium, high.” They monitor during treatment “to try and prevent” toxicity. They treat it if it happens. And then comes the frontier: survivorship and late effects.

“There is a late effect time,” he says. “I’m writing a national UK late effects guideline, which looks at how we can manage the long-term toxicities of cancer survivors.”

Then he offers his definition: “Cardio-oncology is the journey before treatment, during treatment, and after treatment. It’s a holistic coverage of the patient.”

Ethics, Uncertainty, and the Grey Zone

As therapies accelerate, the ethical tension sharpens: saving lives now while avoiding preventable long-term disease later. Ghosh brings the discussion back to the patient.

“At the end of the day, they need to make the decision,” he says. “We can guide them and explain the risks, but the patient needs to decide.”

He describes two broad groups: those who say, “I’m happy to take the risk because I want to live,” and those, often older, who do not want a high-risk intervention that offers only a short extension of life.

The cardio-oncology role, he says, is informed consent and risk minimisation. “Our job is to help with informed consent,” he says. “If the patient wants to go ahead, we help to minimize the toxicity.”

He is also clear about boundaries. “We are not oncologists,” he says. “We are not experts in cancer prognosis.” So, hard cases become the subject of shared decision-making. Many patients sit in what he calls the grey zone. “There is no definite evidence or guideline,” he says.

The tool for that is the multidisciplinary meeting. “We discuss these patients with the oncologist,” he says. “We have cardiologists covering imaging, intervention, and electrophysiology. We have cardio-oncology nurses. We have the oncologists.” The goal is simple: “a holistic view” of the best options.

If Resources are Unlimited

When asked what an ideal global model would look like with unlimited resources, Ghosh answers with a paradox: unlimited resources can be dangerous.

“If you have unlimited resources, you may do too much,” he says. “Just because you can do it does not mean it is required.”

Still, his vision is specific: rapid access and the right amount of surveillance. “You should be able to see the patient the same week,” he says, because delays in cardio review can delay cancer treatment. On monitoring, he wants the optimal number of tests, not the maximum. Too much testing can “cause the patient anxiety.”

Late effects are the hardest dilemma: follow indefinitely, or risk medicalising survivorship forever. “Do you want to completely medicalise this cured patient forever?” he asks. “What about the mental effect of knowing that every year I have a heart scan?”

Then he widens the lens. “A patient told me there was a lack of psychological support,” he says. Cancer patients have major non-medical needs: “workplace support, financial support, psychological support.” He is frank: “We provide excellent medical care, but maybe we are not so great at providing the rest.” Unlimited resources, he says, “would help with that.”

Blitz round: Who is Professor Arjun Ghosh?

- Personal motto: “Have a strategy, but take calculated risks.”

- Favourite city: “London and Kolkata, the two cities closest to my heart.”

- Favourite book and movies: One Hundred Years of Solitude, and childhood classics like Star Wars and Indiana Jones.

- Best advice: “If you don’t go to the party, you’ll never get a chance to dance.”

- Something surprising: “I used to play football. I played with older kids, broke my collarbone, and that was the end of my football career.”

- Most inspiring person in oncology: “Many of my patients.” One survived four cancers and remains “very funny” and “always very positive.”

- Biography title: “A Novel Path With Risks.”

The Field He Built is Bigger than the Heart

As we end, the conversation returns to teaching, not as an accessory to clinical work, but as its continuation.

“The biggest reward I could get is if my trainees and fellows learn and give the optimal care to their patients,” he says, “and if they can be inspired to take the field forward.”

Professor Arjun K. Ghosh speaking at his course

Ghosh has built a clinic, a curriculum, and a fellowship pipeline. He has also helped create a new default: that cancer patients should not have to accept cardiovascular damage as the price of survival, and that cardiology should not treat cancer as a reason to do less.

In the end, cardio-oncology is not simply a medical sub-speciality. It is a refusal to choose between a life-saving cancer therapy and a heart strong enough to live the life that follows.

About the Author

Vahe Grigoryan is a final-year medical student at Yerevan State Medical University, Assistant Managing Editor at OncoDaily. He hopes to pursue a career in oncology, with a strong interest in science, people and stories behind cancer medicine.