May 31 is “World No Tobacco Day” Smoking is one of the major factors for tumors, not only lung cancer. This year’s World No Tobacco Day (WNTD) campaign aims “to reveal the strategies employed by the tobacco and nicotine industries to make their harmful products enticing, particularly to young people. By exposing these tactics, the World Health Organization (WHO) seeks to drive awareness, advocate for stronger policies, including a ban on flavours that make tobacco and nicotine products more appealing, and protect public health”.

WHO organizes the event: “Exposing lies, protecting lives: Unmask the appeal of tobacco and nicotine products”.

Our Co-Editor-In-Chief, Adriana Albini, in collaboration with Francesca Albini, PhD in Philosophy, explores the return of smoking in movies.

A Warning

In recent years, cigarette smoking has reemerged as a striking visual motif in cinema, occupying a space once thought to be fading from popular storytelling. Lit cigarettes dangle from lips in pivotal scenes, clouds of smoke curl through tightly framed shots, and tobacco becomes part of the visual language used to convey depth, rebellion, or intimacy. This resurgence is striking, not only for its aesthetic boldness but for its contrast with the preceding decade, during which the presence of smoking in film had markedly declined in response to growing public health concerns and policy interventions.

The renewed visibility of smoking in cinema has sparked concern among health professionals and researchers. Decades of evidence suggest that tobacco imagery in media can normalise smoking, particularly among adolescents and young adults. As filmmakers revisit the iconography of tobacco, often under the guise of historical realism or character authenticity, the question arises: Are we witnessing a cultural relapse with potential public health consequences?

A Historical Association: Tobacco and Cancer

The relationship between tobacco and cancer is one of the most well-documented—and hard-won—public health discoveries of the 20th century. While tobacco had been cultivated and smoked for centuries, its association with cancer emerged only gradually, and not without resistance.

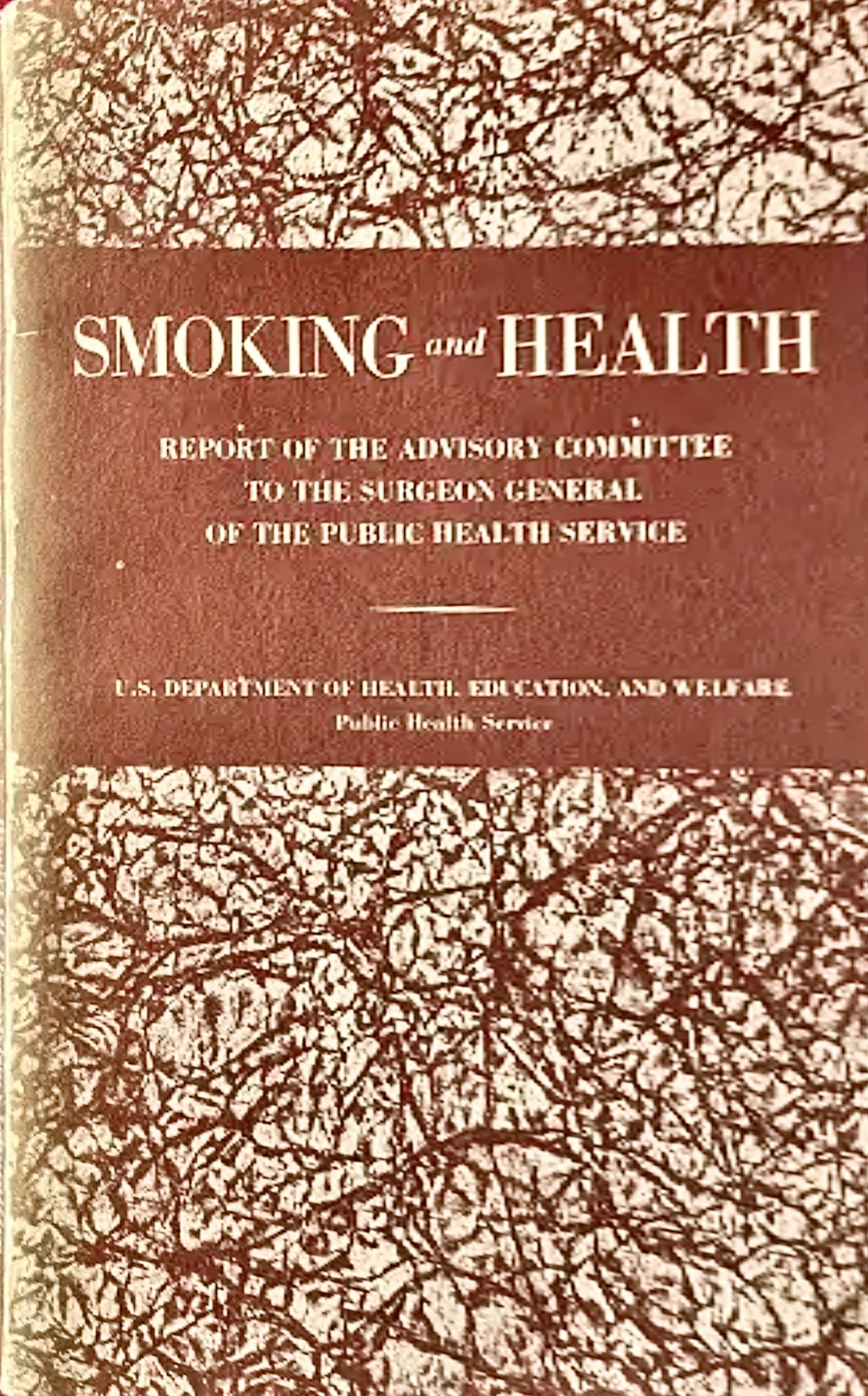

By the early 1900s, physicians in Europe and North America had begun noticing a rise in lung cancer diagnoses, a disease that had previously been rare. Suspicion fell on the growing popularity of cigarette smoking, but early observations lacked the rigor to counter the formidable influence of the tobacco industry. It wasn’t until the 1950s that landmark epidemiological studies provided compelling evidence of causality. In the UK, Richard Doll and Austin Bradford Hill conducted a prospective study of British doctors that established a strong link between smoking and lung cancer. Around the same time in the US, Ernst Wynder and Evarts Graham published case–control studies showing a significant correlation between cigarette use and cancer risk.

These findings culminated in a historic moment in 1964, when the US Surgeon General’s report officially declared cigarette smoking a cause of lung cancer. The report galvanized public health efforts and marked the beginning of a new era in tobacco control. In subsequent decades, further research expanded the list of smoking-related diseases to include cancers of the larynx, esophagus, pancreas, bladder, kidney, cervix, and stomach, as well as myeloid leukemia.

Furthermore, the link between smoking and cancer was not limited to direct users. By the 1980s and 1990s, studies began to show that second-hand smoke exposure also increased cancer risk, leading to widespread public smoking bans in workplaces, restaurants, and, eventually, film sets and studios.

The cultural response was just as significant. Smoking, once glamorised in media and film, began to lose its sheen. Public campaigns reframed it as an addictive, deadly habit rather than a symbol of sophistication. Cigarette advertising was banned from television and sports sponsorships. The tobacco industry, once deeply entwined with Hollywood, was gradually pushed out of mainstream visibility. However, the story is far from over.

Tobacco in Hollywood: From Glamour to Backlash

For much of the 20th century, smoking was not only common in everyday life—it was a cinematic shorthand for allure, danger, introspection, and control. Hollywood’s Golden Age stars, from Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall to James Dean and Marlene Dietrich, lit up on screen with a cool defiance that was both aspirational and carefully constructed.

Cigarettes weren’t just props, they were character cues, emotional punctuation marks, and marketing tools. Behind the scenes, the tobacco industry actively cultivated these portrayals through extensive product placement and covert sponsorship. Archival documents from the 1930s to the 1950s reveal deliberate collaborations between tobacco companies and studios. Actors were paid to endorse cigarette brands in magazines and newsreels, while screenplays were peppered with smoking scenes that reinforced brand familiarity. This wasn’t coincidental, it was a strategic extension of advertising into the emotional core of film. As a result, generations of viewers grew up equating smoking with strength, sophistication, and sexual appeal.

But the cinematic glamour of tobacco began to unravel in the latter half of the century. As scientific consensus about the harms of smoking solidified, advocacy groups and public health organizations turned their attention to the screen. The juxtaposition was becoming untenable: while governments issued warnings and restricted cigarette advertising, films continued to depict smoking without context or consequence.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, mounting pressure led to change. In 2003, the World Health Organization adopted the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), whose article 13 called for restrictions on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship, including indirect forms such as product placement. Around the same time, research emerged showing that adolescents exposed to smoking in films were significantly more likely to try smoking themselves. A study published in The Lancet in 2003 estimated that smoking in films could be responsible for 52% of smoking initiation among young people in the United States.

In response, major studios began to revise their internal policies. The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) introduced guidelines flagging smoking as a content consideration in film ratings. Several studios pledged to eliminate smoking in youth-rated films unless historically justified. The number of tobacco depictions in top-grossing movies began to fall, especially in films aimed at younger audiences. By 2010, the depiction of smoking in mainstream cinema had declined sharply, and it seemed that the once-glorified habit had been relegated to the margins of popular storytelling.

A Quiet Comeback: Smoking in Contemporary Cinema

Despite a clear decline in tobacco imagery through the 2000s and early 2010s, recent years have seen a notable—if understated—resurgence. Smoking is reappearing in arthouse dramas, independent films, and prestige productions. Titles such as Lee (2023), The Brutalist (2024), Oppenheimer (2023), and Blonde (2022) feature cigarette use prominently, not only as a historical or stylistic detail, but often as part of the emotional or visual identity of central characters. This resurgence is not confined to adult-rated films. Analyses by groups such as the Truth Initiative and the University of California, San Francisco, have shown that smoking has also returned to streaming platforms, especially in series popular with adolescents.

Several factors may help explain this quiet return. One is the shift from traditional studios to streaming platforms, which has loosened regulatory oversight. Unlike theatrical releases, streaming content is not held to consistent content rating standards across countries. Guidelines tend to vary between platforms, and decisions about showing tobacco often come down to individual directors or producers. Another reason frequently cited is the pursuit of realism. Period dramas, in particular, rarely avoid cigarettes, with many filmmakers arguing that omitting tobacco from a mid-20th-century setting would compromise historical credibility.

Smoking is also still used as a visual shorthand for mood or personality: to convey defiance, introspection, or instability, especially in stories about artists, outsiders, or troubled lives. But aesthetic realism may also be masking a deeper trend. In a media landscape increasingly shaped by risk-aversion and algorithmic content delivery, smoking may be regaining traction as a visually arresting, emotionally loaded, and narratively efficient tool. It requires no dialogue to convey tension or rebellion. It signals interiority and danger. And in a post-pandemic, post-truth world, smoking—ironically—can feel transgressive again.

Whatever the reason, the reappearance of smoking on screen matters. Studies consistently show that visual exposure to smoking, especially when portrayed by protagonists or romanticized characters, increases the likelihood that young viewers will try smoking themselves. Even when the character is morally ambiguous or the context is historical, the act of smoking on screen remains a behavioural cue. The risk is not just theoretical: tobacco use among adolescents in several countries has plateaued or increased in recent years, with media exposure identified as a contributing factor.

Visual Exposure and Cancer Risk

The relationship between onscreen smoking and public health is not merely associative—it is causative, cumulative, and of direct concern to oncology. Repeated exposure to tobacco use in media, particularly film and streaming platforms, has been shown to increase smoking initiation among adolescents and young adults, a pathway that directly contributes to long-term cancer risk.

A landmark 2012 report from the US Surgeon General concluded that “there is a causal relationship between depictions of smoking in the movies and the initiation of smoking among young people.” Since then, multiple large-scale studies have quantified this effect: adolescents with the highest exposure to tobacco use in films are roughly two to three times more likely to begin smoking compared to their least-exposed peers. A 2020 meta-analysis found that for every 500 tobacco impressions viewed in movies, the odds of adolescent smoking initiation increased by 39%.

Tobacco remains the leading preventable cause of cancer worldwide. It is implicated in at least 15 types of malignancy. Globally, smoking is responsible for over 1.8 million cancer deaths per year, according to the most recent IARC estimates. Among these, lung cancer remains the most lethal, accounting for more than 80% of tobacco-related cancer mortality.

What makes onscreen exposure especially potent is its ability to normalize smoking without showing its consequences. In most films where smoking is depicted, there is no mention of addiction, disease, or death. Characters smoke without coughing, without diagnosis, without repercussion. This discrepancy reinforces the myth of the “social smoker,” the illusion of control, and the separation of smoking from its long-term health outcomes.

From a public health perspective, exposure to tobacco imagery in entertainment is now widely recognized as a modifiable cancer risk factor. Both the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have issued recommendations urging the film and streaming industries to reduce or eliminate tobacco portrayals, especially in content accessible to youth. Suggested measures include:

- Assigning adult ratings to films and series with smoking

- Including anti-smoking PSAs before content with tobacco imagery

- Requiring clear labelling of tobacco use in content advisories

- Ending public subsidies for productions that depict smoking

While voluntary adoption has been uneven, the rationale is clear: limiting onscreen tobacco exposure is a form of cancer prevention.

Vaping and the Visual Shift

While vaping has surged among adolescents and young adults, its depiction in film and television remains relatively limited. Unlike cigarettes, vaping devices lack the cinematic weight that once made tobacco a storytelling tool. When e-cigarettes do appear, it is often in the margins: a futuristic flourish in science fiction, a visual shorthand for tech-savviness, or a throwaway joke in teen comedies. Rarely are they framed with the same emotional or aesthetic significance once reserved for cigarettes.

This absence is notable given the scale of the vaping epidemic. In many countries, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom, e-cigarette use among adolescents has surged over the past decade. According to the CDC, more than 2 million middle and high school students reported current e-cigarette use in 2021. In the UK, similar trends have been observed, with a notable rise in underage vaping, often facilitated by flavoured disposable devices.

The oncological concerns around vaping are twofold. First, while e-cigarettes may contain fewer carcinogens than combustible tobacco, they are not harmless. Heating elements in some devices produce formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acrolein, compounds with known mutagenic and cytotoxic properties. Moreover, flavouring agents such as diacetyl have been implicated in chronic respiratory conditions, and emerging studies suggest that chronic e-cigarette exposure may lead to DNA damage, impaired repair mechanisms, and oxidative stress—hallmarks of carcinogenesis.

Second, and perhaps more critically, vaping often serves as a gateway to smoking, particularly among youth. Longitudinal studies have shown that adolescents who begin with e-cigarettes are significantly more likely to transition to combustible tobacco products, a progression that reopens pathways to the very cancer risks that decades of tobacco control sought to close. The World Health Organization and major cancer research agencies have therefore taken a cautious stance, warning against the normalization of vaping, particularly in media accessible to young audiences.

In response to these concerns, the European Union has implemented comprehensive regulations on the marketing and sale of vaping products. The Tobacco Products Directive (2014/40/EU), effective since May 2016, prohibits cross-border advertising and promotion of e-cigarettes in various media, including television, radio, print, and online platforms. It also mandates health warnings on packaging, restricts nicotine content, and requires child-resistant packaging for e-cigarette products.

Building upon these measures, Belgium has taken a pioneering step by becoming the first EU country to ban the sale of disposable e-cigarettes, effective January 1, 2025. This decision, approved by the European Commission, is part of Belgium’s broader anti-tobacco strategy aimed at protecting public health and the environment. Health Minister Frank Vandenbroucke emphasized that disposable e-cigarettes are particularly attractive to young people due to their low cost and appealing flavours, leading to increased nicotine addiction among youth. Additionally, the environmental impact of these single-use devices, which contain plastics and lithium batteries, contributes to hazardous waste. Following Belgium’s lead, France enacted a similar ban on February 26, 2025, prohibiting the sale and distribution of disposable e-cigarettes, commonly known as “puffs.” This legislation aims to protect adolescents from nicotine addiction and address environmental concerns associated with these devices. In Italy, while a complete ban on disposable e-cigarettes has not been implemented, the government introduced stricter regulations in January 2025. These include increased taxation on nicotine-containing e-liquids and a ban on the online sale of nicotine products, measures intended to curb youth access and align with traditional tobacco product regulations.

The United Kingdom has also announced a ban on the sale and supply of single-use vapes, set to take effect on June 1, 2025. This measure, part of the broader Tobacco and Vapes Bill, aims to address the environmental impact of disposable vapes and reduce their appeal to young people. The legislation prohibits the sale of single-use vapes across England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, with businesses required to deplete their stocks before the enforcement date.

While cinematic depictions of vaping remain limited, social media platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube have filled the visual void. Vaping tutorials, lifestyle content, and influencer marketing have created a parallel universe of visual exposure, often devoid of regulatory oversight. The narrative may have shifted from the silver screen to the smartphone, but the implications for public health and cancer prevention remain pressing.

Whether the film and television industry will begin to reflect the ubiquity of vaping in real life, or consciously avoid it as part of a harm reduction effort, remains to be seen. In the meantime, the muted presence of e-cigarettes on screen may represent a rare window of opportunity: to prevent the glamorization of a product whose long-term health consequences are still unfolding.

Policy, Prevention, and Public Responsibility

The return of smoking to film and television is not just a stylistic or narrative development—it raises important questions for public health, particularly in the context of cancer prevention. For oncology professionals and researchers, how tobacco and vaping are portrayed in popular media remains a relevant and unresolved part of the broader effort to reduce avoidable cancer risk. Public health bodies have long recognized the media’s role in shaping behaviour. The WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) explicitly calls for a ban on all forms of tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship, including indirect promotion through film and streaming content. Despite this, enforcement has been uneven, particularly in the digital age, where content transcends borders and platform accountability remains limited.

In the European Union, the Tobacco Products Directive remains the cornerstone of e-cigarette regulation. While it addresses advertising and labelling, it does not yet cover the nuanced depictions of vaping and tobacco use in entertainment media. Health advocacy groups, such as the European Cancer Leagues and the European Respiratory Society, are now calling for the inclusion of visual tobacco exposure within broader cancer prevention strategies. The European Beating Cancer Plan, launched in 2021, recognizes tobacco control as a key pillar of cancer prevention, but its implementation in media policy is still evolving.

Tobacco remains the leading preventable cause of cancer in Europe, responsible for approximately 700,000 deaths annually. Every measure that reduces smoking initiation, particularly among young people, directly translates to future reductions in cancer incidence and mortality. Reducing visual exposure is one such measure.

Several Recommendations Have Emerged from Public Health Agencies, Including:

- Assigning adult ratings to films and series that depict smoking or vaping, except when used to portray its harmful effects or for historical accuracy.

- Requiring disclosure statements that certify no tobacco industry influence or funding.

- Including anti-smoking messages or disclaimers before films containing tobacco imagery.

- Prohibiting public subsidies for productions that include smoking without a public health justification.

- Expanding media literacy campaigns to educate young viewers on how smoking and vaping are used as narrative devices.

As the cultural pendulum swings, the window to prevent a new generation of tobacco-related cancers may narrow. The cinematic comeback of smoking is not yet a crisis, but it is a cautionary signal. In the face of evolving media habits, shifting aesthetics, and emerging nicotine products, cancer prevention must extend beyond the clinic and into the cultural spaces where risk is quietly rehearsed and behaviour takes root.