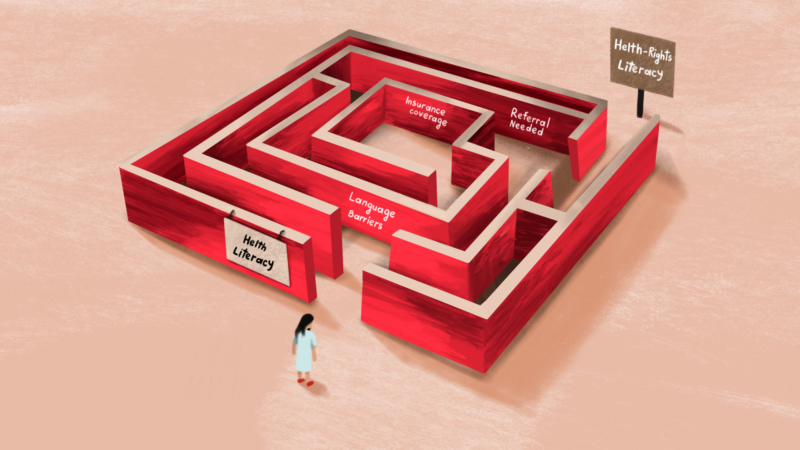

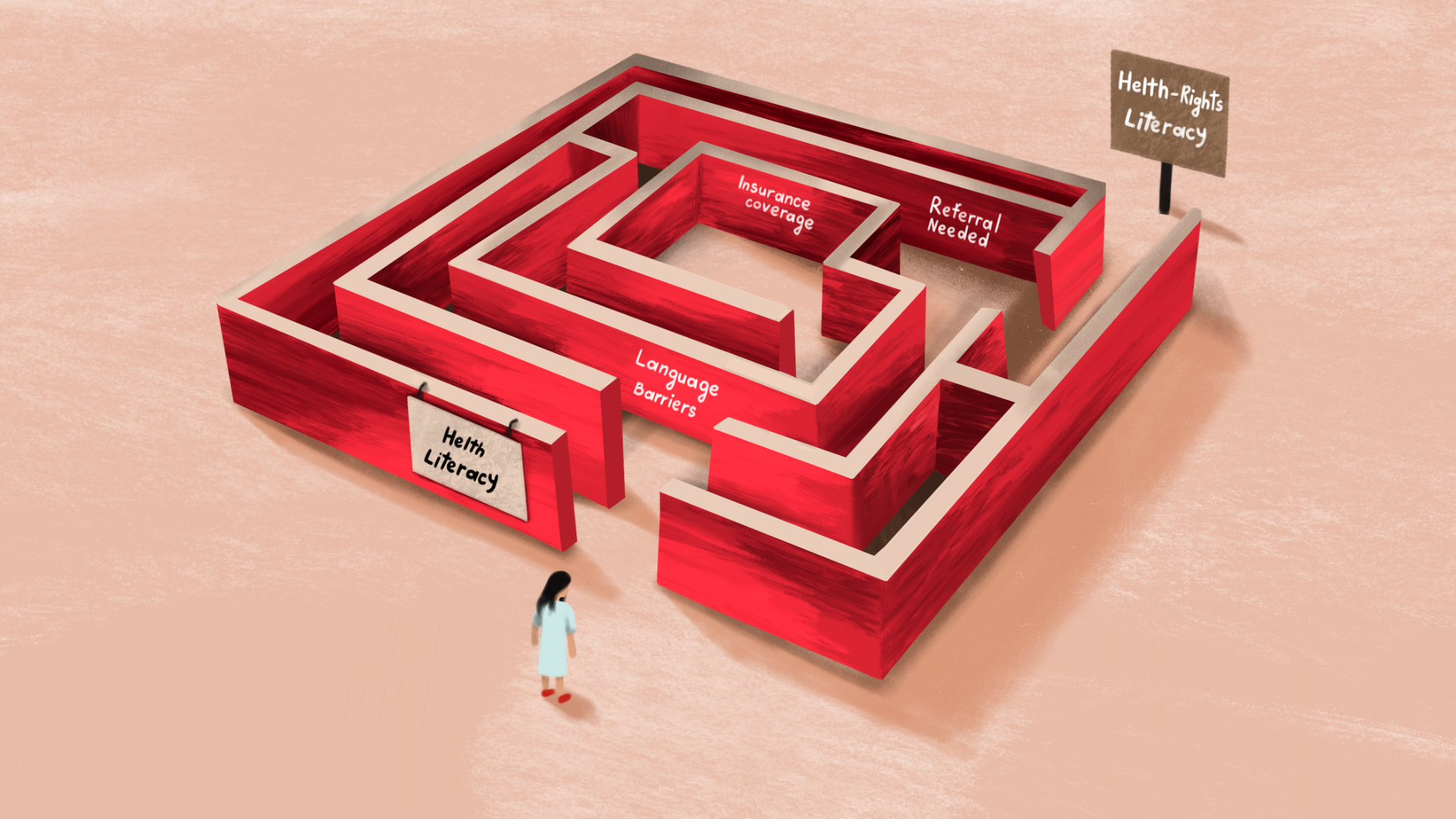

Across Europe, cancer-prevention messages have become increasingly visible: mammography after age 50, HPV testing at 30, colorectal screening from mid-life onward. These messages reflect years of investment in health literacy and promotion. Yet a critical question persists: when citizens know what to do, do they also know how to use this knowledge while navigating within their own healthcare system? To bridge this gap, it is useful to introduce a complementary concept: health-rights literacy. While “health literacy” concerns understanding health information, health-rights literacy encompasses knowing one’s entitlements, where and how to access care, what is covered, and which steps are required to use services without bureaucratic or linguistic barriers.

What the Evidence Shows: Awareness Is Rising, Navigation Still Lags

The European Union’s 2022 Council Recommendation aims for 90% of eligible citizens to receive organised screening invitations for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer by 2025 [1]. Evidence shows that participation improves notably when invitations are systematic, personalised, and easy to act on.

However, evidence suggests that improving awareness alone may not suffice. Studies have shown that health literacy did not strongly predict participation in three national screening programmes, stressing the need for actionable information for all recipients of health information, and particularly the most vulnerable ones [2,3].

For vulnerable groups, the barriers are deeper. A recent review focusing on hepatitis B and C screening in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) identified multiple barriers to the comprehension and uptake of screening recommendations among migrant populations in the region [4]. It appears that booking procedures, referral rules, insurance coverage, and communication formats can often be unclear.

The European Landscape: Geography, Language, and System Design Geographical Diversity

Across Europe, regional inequalities remain strong. Remote and island areas—from the Greek archipelago to Sardinia, the Balearics, and parts of rural Eastern Europe—often lack nearby screening facilities. Mobile mammography units exist in countries like Greece and Portugal, but covering the needs of the population in relation to their occupational and/or family obligations may be challenging. In Greece, island-based access has long been a challenge. Mobile units operated by public hospitals or NGOs, or private donors, periodically visit islands such as Naxos, Chios or Samos. Booking information is usually provided in calls available online – and presumably also offline in local press – but booking requires advance notice and local awareness campaigns. For many older women, booking online is not intuitive—even when the service itself is free.

Health-System Pathways

Countries with invitation-based programmes (e.g., France, the Netherlands) generally achieve higher participation rates. In systems with a central coordinating role reserved for primary care, the GP acts as a guide. These regional differences may affect the journey of expats or migrants to healthcare, especially in case their process of registering with local healthcare authorities/general practitioners is incomplete or subject to relocation/asylum seeking processes. Particularly with regard to displaced individuals, maintaining a continuum of screening and transferring health-related information from country to country may be challenging, as already reported in the context of pediatric care among migrants [5]. EU initiatives such as the EU Health Data Space (EHDS) prompting interoperability of healthcare services, are promising in this regard [6].

Language and Dialect Barriers

For migrants or linguistic minorities, barriers often relate not only to awareness but also to communication formats [7]. Countries such as Greece, Italy and Germany host substantial communities speaking Albanian, Arabic, Russian, Georgian, Armenian, Urdu and Farsi, yet most screening information remains monolingual, issued in the official language of the host country, or in some cases translated only into the official languages of the EU. Providing instruction in the languages used by migrants would enhance their ability to comprehend and participate in screening programmes.

The presence of a number of dialects of official EU languages must also be noted in the context of health-rights literacy. Providing audio-based content in dialects such as Cretan, Ionian or Pontic Greek, or Grecanico in Calabria (Italy), for instance, could strengthen trust as well as awareness among users of these dialects — especially older people and/or members of rural communities.

A further step in breaking communication and comprehension barriers — beyond and within languages — would include sociolects, defined as language varieties used by demographic or social groups. The so-called Gen Z “slang”, a dynamic mix of national languages and internationally used English terms, is a representative example of a sociolect. Exploring messaging in this format could enhance the actionability of information by using words closer to the audience’s everyday life, rather than a standardised and psychologically distant medical language.

Moving Forward: Integrating System Literacy into Every Screening Effort

A more actionable and equitable approach to cancer screening requires that every awareness effort move beyond information provision to concrete guidance. First, campaigns must be operational, providing clear instructions on where screening can be accessed, how appointments are booked, whether referrals are needed, whether the tests are free, and what happens next.

Second, campaigns should communicate across languages and dialects. Public messages ought to be available not only in multiple and commonly spoken languages, with additional audio adaptations in local dialects for radio or television in regions where dialects remain widely spoken. Such communication acknowledges the country’s linguistic diversity and reinforces the principle that screening is a universal right, not a privilege reserved for speakers of the dominant language.

Third, messaging needs to be linked to local services. Effective campaigns integrate municipal health offices, mobile mammography units, primary care structures, public hospitals, and civil-society organisations. When recipients of a campaign know precisely which local service they can turn to—and how to reach it—awareness is transformed into access.

Finally, the strategic use of digital governance tools can significantly enhance participation. Digital health wallets, SMS reminders, secure online portals and pre-booked appointment slots have already demonstrated impact in countries such as Greece [8]. Extending these tools to additional screening domains—for example, mailing FIT kits for colorectal cancer screening with QR-code–based activation—can streamline pathways, reduce inequalities, and ensure that individuals are supported at each step from invitation to follow-up. Caution should be exercised to match the complexity of the intervention with the digital literacy and access of the target population.

Conclusion

Europe has built a strong foundation for cancer-screening awareness. The next step—necessary, achievable, and equity-enhancing—is embedding navigation support into every message. Health-rights literacy captures this shift: it recognizes that people do not only need to know why screening matters, but also how to use their rights within a real healthcare system.

Briefing Box

Turning Awareness into Access: Four Steps to Strengthen Health-Rights Literacy

- Always include practical instructions.

Public campaigns should explain how to book a screening, whether it is free, and if a referral is needed. - Reach people in their language.

Provide materials in national languages, local dialects, and key migrant languages (Arabic, Albanian, Serbian, Ukrainian, Turkish, etc.). - Connect campaigns with real services.

Work with community clinics, mobile units, and primary-care providers to offer locally relevant pathways.

Use digital tools to simplify access.

SMS invitations, digital health wallets, integrated booking systems, and personalised reminders significantly increase uptake and reduce inequalities.

About the Author

Christos Tsagkaris, MD, MPA, MSc, is a medical doctor from Greece working as a clinician and researcher in Switzerland. In parallel, he is involved in institutional bodies and civil society organisations working on cancer prevention, control and crisis preparedness

References

- European Commission Council Recommendation on Cancer Screening (2022).

- Oldach BR, Katz ML. Health literacy and cancer screening: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(2):149-157. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.001

- Helgestad ADL, Karlsen AW, Njor S, Andersen B, Larsen MB. The association between health literacy and cancer screening participation: A cross-sectional study across three organised screening programmes in Denmark. Prev Med Rep. 2025;53:103022. Published 2025 Mar 14. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2025.103022

- Moonen CPB, den Heijer CDJ, Dukers-Muijrers NHTM, van Dreumel R, Steins SCJ, Hoebe CJPA. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators for hepatitis B and C screening among migrants in the EU/EEA region. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1118227. Published 2023 Feb 15. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1118227

- Tsagkaris C, Eleftheriades A, Moysidis DV, et al. Migration and newborn screening: time to build on the European Asylum, Integration and Migration Fund?. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2022;27(5):431-435. doi:10.1080/13625187.2022.2088729

- Stellmach C, Muzoora MR, Thun S. Digitalization of Health Data: Interoperability of the Proposed European Health Data Space. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2022;298:132-136. doi:10.3233/SHTI220922 .

- Evenden R, Singh N, Sornalingam S, Harrington S, Paudyal P. Language barriers for primary care access in Europe: a systematic review: Priyamvada Paudyal. Eur J Public Health. 2022;32(Suppl 3):ckac129.724. Published 2022 Oct 25. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckac129.724

- Kontogiannatou A, Liaskos J, Gallos P, Mantas J. Usefulness, Ease of Use, Ease of Learning and Users’ Satisfaction of E-Prescription and E-Appointment Systems for Primary Health Care. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019;262:210-213. doi:10.3233/SHTI190055