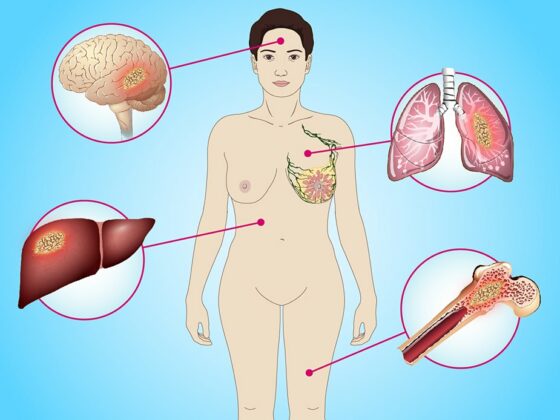

The speed of progress in breast cancer – not just survival, but also quality of life and survivorship – has been the envy of the wider cancer community for many decades. The factors contributing to this relative success are many – the role played by Hansjörg Senn, who died on January 13th, should be acknowledged as one of them.

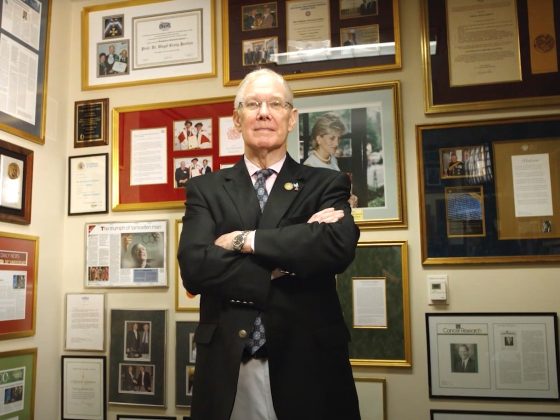

Born the son of a notary lawyer in a small town near Zürich, Senn graduated from Zürich University medical school in 1961, just as medical oncology was beginning to show what it could do. A year’s postgraduate residency in internal medicine at Duval Medical Center in Florida, followed soon after by a two-year research fellowship in the Medical Oncology and Hematology department, at Roswell Park Cancer Institute in New York (state), set him up for a career in oncology that began with a four-year stint as attending physician and senior investigator at Basel University Hospital’s Division of Onco-Haematology.

In 1973 Senn moved to St Gallen, a city overlooking Lake Constance, located around 70 km from his home town, with less than half the population of Basel, to take up a post as Co-Chair of the Department of Internal Medicine and Head of the Division Oncology-Haematology at the St Gallen cantonal hospital. If the name of the city sounds familiar – as it will do to almost any breast oncologist and advocate, and many more in the wide cancer community – it is because of Senn, and what he achieved while he was there.

It was Senn who took the lead in launching what would become the ‘St Gallen conferences’, where international experts gather every other year to review and reach a consensus on the latest evidence on the primary therapy of early breast cancers.

Convened for the first time in 1978 as a gathering of the pioneering triallists of adjuvant chemotherapy, those conferences have guided clinicians everywhere through the confusing rollercoaster that has transformed breast oncology from a one-size-fits-all treatment reliant on radical surgery and still plagued with high levels of recurrence, to the precision treatment approaches combining multiple treatment modalities in different combinations for different stages, subtypes and patient needs and preferences that are still in development today.

At a time when medicine was still heavily ’eminence’ rather than ‘evidence’ based, the ability – for which the Swiss are well known – to bring together an inclusive meeting of the respected opinion leaders and facilitate discussions to forge a consensus was crucial not just as an academic exercise, but for rapidly driving change in standards of care.

These authoritative consensus guidelines sent a clear message to breast cancer doctors, and to patients and advocates: whatever you may have been taught, whatever you may believe, this is how the latest evidence shows you should diagnose, treat and care for your patients. And while the conferences have now moved from St Gallen to a larger venue in Vienna, it continues to send out those clear messages every two years.

Breaking with consensus

Senn was not only a consensus maker. He was also prepared to break the consensus when the scientific rationale, evidence and potential benefit pointed in that direction. One his first initiatives, on taking up his post in St. Gallen, was to start a programme of giving adjuvant chemotherapy treatment to his patients with early breast cancers.

This was only a year or two after the start of the pioneering adjuvant breast cancer trials led by Gianni Bonadonna in Milan and Bernie Fisher in the US. Speaking to Cancer Futures (the forerunner to Cancerworld) in 2004, Senn remembered how isolated they were in those early days. “At that time adjuvant treatment wasn’t seen as innovative, it was seen as absolutely crazy, and we were heavily criticised by the medical oncologist community. We were ostracised for putting healthy women on chemotherapy.”

It was the need to gather and make sense of the totality of evidence being generated by increasing numbers of adjuvant breast cancer trials that prompted the first international gathering of breast cancer specialists in St Gallen. Bonadonna and Fisher were there, together with Aron Goldhirsch, Richard Gelber and Alan Coates – all leaders within the breast cancer clinical research community.

This was in 1978, with 78 people on the attendance sheet – all of them triallists. The exercise was repeated in 1984 and then again in 1988, which is when the consensus format was adopted. And the attendance expanded well beyond the group of triallists for whom it was originally intended. “We began to realise that breast cancer is not just treated by triallists, but by virtually every hospital across the world,” Senn told Cancer Futures. That realisation is key to the enormous impact the St Gallen conferences continue to wield.

As systemic cancer treatments entered the market at an increasing pace, Senn played a key role in efforts to pull together many of the larger breast cancer collaborative trials groups to build a critical mass of academic researchers. He was one of the founders of the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) and he led it as first Foundation Council President between 1990 and 1995. This study group, which now includes groups across Europe, Australasia, Africa, Asia, North and South America – together with the overarching organisation the Breast International Group BIG – can take much of the credit for the relatively rapid progress made in breast cancer treatment and care over those decades. It allowed academic researchers a level of influence in driving the research agenda – determining which questions to ask, how to ask them, how to report the results – that has long been the envy of researchers and advocates in other parts of the cancer community.

Gelber, who worked closely with Senn in international breast cancer research over four decades, and who remains the senior biostatistician for the IBCSG, says the founding of the IBCSG was driven by Senn’s commitment that a decision to close the Ludwig Breast Cancer Study Group – which had been key to their international collaborations – would not spell the end of their international breast cancer collaborations. “In 1990, Hansjörg invited Aron Goldhirsch and me to lunch at a hotel in the mountain town of Splügen, Switzerland. Hansjörg informed us that ‘no matter what’ he would find the means to continue the work started by the Ludwig Group – and that we should continue the impactful research under the name of the International Breast Cancer Study Group.”

Championing quality of survival

Pivotal though he was in coordinating international efforts to push up survival in early breast cancer, Senn was also quick to recognise the damage done by chemotherapy, and the need to develop strategies to manage toxic effects. In his 2004 interview with Cancer Futures, Senn talked about a growing recognition, by the early ‘80s, that the rapid progress in finding new cytostatics able to cure some disseminated cancers, such as leukaemias, lymphomas and testicular cancer, was beginning to “plateau out”, and there were a lot of patients for whom treatment would remain palliative, “so the balance between effects and side effects was coming increasingly into question.” He credited Agnes Glaus, chief nurse at St Gallen’s Interdisciplinary Cancer Centre, where Senn was chairman between 1982 and 1997, for driving home to him the importance of this issue.

His response was to convene a meeting to share knowledge and best practice and foster international collaboration around this topic. Together, Senn and Glaus searched the literature for anyone who treated and managed pain, or nausea and vomiting, or infections, and in February 1987 they convened a meeting on Supportive Care in Cancer Patients. It was the first such international meeting ever held. Around half of the 700 people who attended were specialist nurses, particularly from the US and Australia, and around 75 countries were represented in all.

His response was to convene a meeting to share knowledge and best practice and foster international collaboration around this topic. Together, Senn and Glaus searched the literature for anyone who treated and managed pain, or nausea and vomiting, or infections, and in February 1987 they convened a meeting on Supportive Care in Cancer Patients. It was the first such international meeting ever held. Around half of the 700 people who attended were specialist nurses, particularly from the US and Australia, and around 75 countries were represented in all.

This was the beginning of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC), which continues to lead efforts in the practice, education, and research of supportive care in cancer, with its journal Supportive Care in Cancer, which was formally established at that first meeting, and started publication in 1993, with Senn as Editor in Chief.

Always looking for strategies to minimise unnecessary pain and suffering, Senn was also a big believer in prevention and was deeply immersed in research to define genetic and other markers of risk and issues in screening and medical prevention. In 1988, he left his post at the head of St Gallen’s Multidisciplinary Cancer Centre to found an independent clinical institute, the centre for cancer diagnosis and prevention (ZeTuP), in the same city (which last year became part of the Eastern Switzerland Cancer and Breast Centre). He was General Secretary, and then Treasurer of the International Society of Cancer Chemoprevention (ISCaC) for many years, from 2003, and co-chaired a series of St Gallen conferences on cancer prevention, which were cosponsored by the major European, US and international professional, educational and research societies. Conference proceedings were published as part of the ‘Recent Results in Cancer Research’ series that Senn edited for more than 25 years.

Spreading the knowledge

Senn’s impact, within European oncology in particular, was magnified by his lifelong commitment to helping educate younger generations of physicians and nurses alike to master the scientific, human and ethical knowledge and skills required to give patients everywhere the full benefit of this complex and rapidly developing field of medicine.

He led the German-language educational programme of the European School of Oncology between 1996 and 2010. The opportunity to learn in ones native language he recognised as essential for nurses, most of whom were not university educated in those days, at least in German-speaking countries. But even among physicians, Senn argued that English was fine for medical discussion, but when it came to learning about how to break bad news and conduct sensitive discussions about prognoses and options, that had to be done in the mother-tongue.

As Glaus remembers, the 1970s, when Senn first started working in St Gallen, was the era when health professionals in Europe really started learning about how best to care for cancer patients, “as it was only then when cancer wards were opened in European hospitals.” Many European oncologists, like Senn, had spent time training in US cancer centres, where they had seen specialist cancer nurses at work, and they were very thankful, she says, to find nurses back home who wanted to care for cancer patients.

“Truth telling was a major challenge,” she says, “and we learned that an interdisciplinary team was needed to provide best treatment and supportive care. It took only a short time until it was clear that specialisation in oncology was essential. Hansjörg Senn supported all efforts to establish postgraduate education in the early ‘80s for nurses and for physicians. He was a good teacher and leader and enjoyed seeing professionals becoming competent colleagues.”

Glaus remembers Senn as someone who was hard working and always full of initiative – “nothing was too much for him”. He enjoyed caring for very ill patients, she says, but also was happy to do research to develop more successful treatments. “He also enjoyed seeing the light and bright sides of life and his sense of humour helped him a lot to live with reality. No question that his strong Christian faith was a solid pillar in his life.”

Diagnosed with malignant lymphoma in 2016, aged 82, Senn wanted his treatment to be done at ‘his’ cancer centre, says Glaus. “He wanted to live!” The treatment was really tough, she says, but he got through it, and “became a survivor!” Despite other health issues that gave him pain and impaired is mobility, Senn remained active and enjoyed life until the end, she says. “Even in the last months of his life he enjoyed short walks at the Bodensee [Lake Constance] – looking at the other shore of the lake and enjoying the wonderful scenery.”

Gelber remembers Senn as a doctor and researcher who always wanted the best for patients and was a pleasure to work with. Now Professor of Biostatistics at the Harvard T H Chan School of Public Health, and Professor of Biostatistics and Computational Biology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Gelber numbers himself as one of “countless investigators who was inspired by Hansjörg Senn to do their best by fostering breast cancer clinical trial research to improve patient care.”

“Hansjörg was a true gentleman, who was respectful, thoughtful, and always considered the well-being of his patients and all of those who worked with him. He created environments in which, together, he and others could have a profound impact to improve the lives of patients worldwide,” says Gelber. “In addition to his leadership of the IBCSG as its first Foundation Council President, I will always be grateful for Hansjörg’s creation of the St Gallen Breast Cancer Conference. I was fortunate to work closely with him, Alan Coates and Aron Goldhirsch to develop the format for this extraordinary, worldwide guidelines-setting conference. Hansjörg was an inspirational leader; we owe him our deepest gratitude.”

Hansjörg Senn is remembered by the team at the St Gallen Oncology Foundation (SONK) as “a deeply respected colleague, physician and warm-hearted friend. We will remember him for his kindness and his wisdom, his commitment to excellence in cancer care. As a dedicated cancer researcher and physician, he made the world a better place.”

Senn’s many awards include the 2003 European FECS/Pezcoller-Award for Lifetime Achievements, the European Society for Medical Oncology 2011 Lifetime Achievement Award, and recognition by the German Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics as one of “The Big Four of the Millennium”, alongside Umberto Veronesi, Craig Jordan and Harald Zur Hausen.