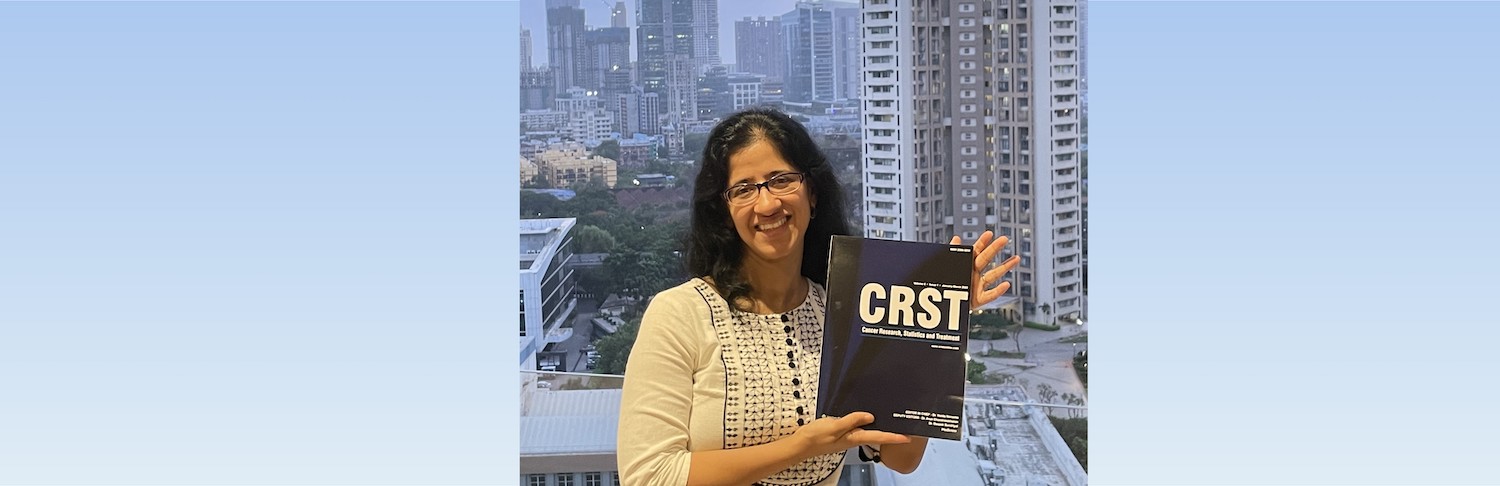

We launched Cancer Research, Statistics and Treatment at the internationally renowned Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, in 2018. It was my colleague, Professor of Medical Oncology, Kumar Prabhash, who prodded me to start the journal. I had already been the Editor-in-Chief of South Asian Journal of Cancer, but had stopped to focus on my clinical commitments and research. With his support, I took on the task of starting a journal that published Indian research and reflected the realities of patients in low- and middle-income countries.

We decided not to position it as a ‘global oncology’ publication, because our aim was to be the best high-quality resource for oncology. We thought, if the New England Journal of Medicine can start from Harvard as an institutional journal and become the definitive medical journal for the entire world, what’s stopping us? We have more than a billion people, why can’t there be a high-quality journal from India?

Most reputed medical journals come from Western countries and are based on their populations and their evidence. We can’t just ‘cut and paste’ those data and guidelines for our patients, because we differ based on our ethnic background and even our genetic make-up. One way to solve this is to conduct studies and produce the data, and the second is to disseminate the data. That’s where we come in.

If the New England Journal of Medicine can start as an institutional journal and become the definitive medical journal for the world, what’s stopping us?

There is a lot of Indian data, but most high-quality global journals are European or American and there is often an implicit publication bias where they do not view Indian studies to be on par with those conducted in the West. At the moment, there aren’t enough high-quality Indian journals. The problem is most editors in India are clinicians and not trained in editing. Since there is no dedicated team that works on the journal and no incentive, everyone does editing in their spare time. With their own clinical workload, editing is relegated to the sidelines and the quality of the journal suffers.

Our unique offerings

With most Indian journals, the timelines are long; the turnaround time for articles can be upwards of a year or two years. To put that in perspective, if my study finds something relevant to the care of patients it should inform the care of patients in the clinic now, it is unethical for it to remain unpublished with a journal for two years before it gets disseminated. In CRST, our timelines for first decision – to review or reject – is 30 days, and the time for final decision – to accept or reject – is 40–45 days. We follow up with our reviewers to ensure the timelines are maintained.

Our target readership is everyone who takes care of cancer, so primarily doctors, and we also have certain niche sections in our journal for patients, for caregivers, for trainees etc. We are positioning ourselves as being somewhat of a broad journal. Most of our readers are from the United States (32.1%), followed by India (21.4%) and United Kingdom (6.4%). Among the top ten cities with the most readers, New York and Chicago feature among other Indian cities, which was very heartening for us.

“Most of our readers are from the United States (32.1%) followed by India (21.4%)”

At the moment, we get more submissions than we can possibly accept. This is probably the situation for most journals, but not for new journals. One of the reasons is indexing. We are currently indexed in Scopus and we will shortly be applying to PubMed. Our Scopus cite score – a measure of how often articles in our journal are cited – is 4.8. That’s an achievement, if you compare it with other Indian oncology journals such as the Indian Journal of Cancer, which has been published for 40 years and has a cite score of 1.6, or the South Asian Journal of Cancer, whose cite score is 1.5, or the Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology, at 0.5. This shows that our readers find us valuable.

Challenges

One of our main challenges is finding people who are willing to put in the effort, because all of it is unpaid labour. In the whole process of publishing the journal, the only people getting paid are the publishers. The editorial board doesn’t get paid. We don’t charge authors for submissions and we don’t charge for access to our journal. Indian clinicians do not have a strict requirement to publish a certain number of articles. If there were an incentive to publish, it would be easier to get more financial support. Our journal is owned by the Cancer Research and Statistics Foundation, but we get limited funds and most of it is used to pay the publishers. There is no money to pay additional supporting staff. I had considered closing the journal last year but Rajendra Badwe, Director of Tata Memorial Hospital, stepped in and funded two editorial assistants through the institute.

We need funders to come forward and fund us so that we can hire trained staff who can help edit the journal. We are confident that once CRST becomes a definitive journal among the top in the world, more people will be willing to join us. To sustain the publication till then is the challenge.

Vanita Noronha is Professor and Medical Oncologist, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai and the Editor-in-Chief of Cancer Research Statistics and Treatment.