Alcohol can be bad for your health. Most people know that. But what many people have yet to grasp is that ‒ like smoking tobacco ‒ drinking alcohol can significantly raise their risk of developing and dying from a wide range of cancers. According to the World Health Organization, in the EU+ countries, cancer was the main cause of deaths due to alcohol in 2016, accounting for almost 3 in 10 alcohol-attributable deaths, followed by liver cirrhosis, cardiovascular disease and injury.

Getting that message across, and changing behaviours, is a particular issue for cancer control in Europe, which leads the world in alcohol consumption.

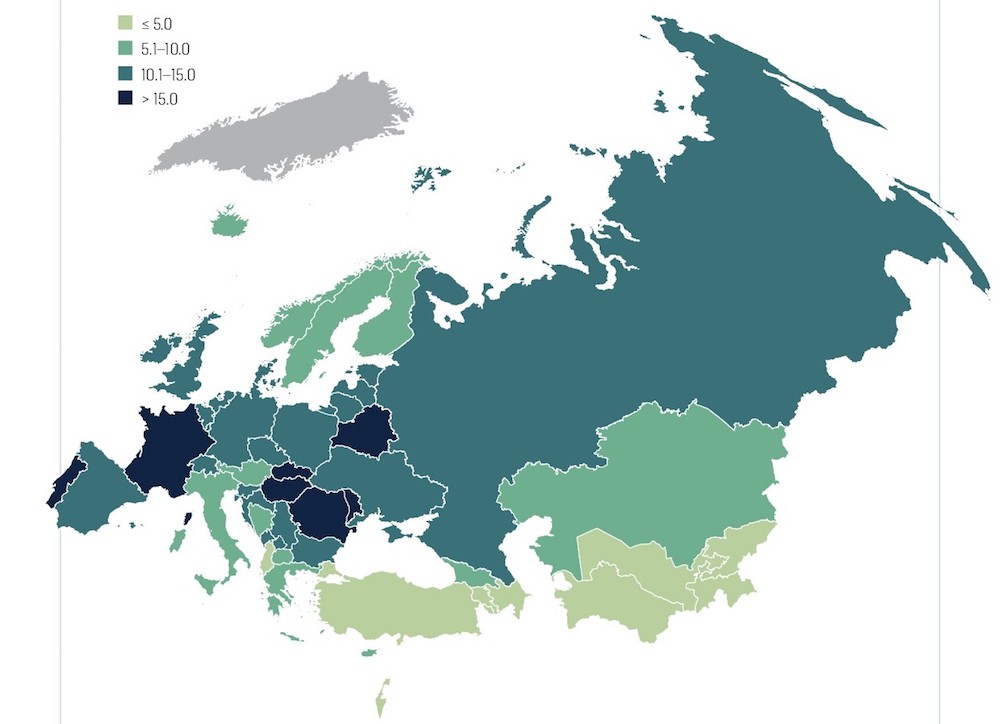

The World Health Organization estimates per capita consumption in its European region (2016 data) to be 50% higher than the global average (9.98 vs 6.4 litres/adult/year). Estimates from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) indicate that, of the 4.2 million cancers diagnosed in the WHO European region in 2018, 4.3% ‒ i.e. almost 1 in 20, or 180,000 in all ‒ could be attributed to alcohol. Those figures vary significantly between countries; in Turkey for instance, fewer than two per 100,000 people are diagnosed with a cancer attributed to alcohol, while in Hungary and Romania that figure rises ten-fold to almost 20 per 100,000.

Age standardised rates of cancer cases in the WHO European region caused by alcohol, per 100,000 (2018)

It was no surprise therefore to see alcohol control feature in the European Commission’s Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan, which was launched February 2021. The Commission has set a target to achieve a relative reduction of at least 10% in the harmful use of alcohol by 2025. To get there, the Commission says it will “increase support for the Member States and stakeholders to implement best practices and capacity-building activities to reduce it”. In addition, it will review EU legislation on the taxation of alcohol and cross-border purchases of alcohol by private individuals. This article will have a look at the alcohol policies of three EU countries with different experiences in alcohol regulation.

Alcohol and cancer

IARC classifies alcohol consumption as a human carcinogen in the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, oesophagus, colorectal, liver and female breast cancers.

Biology

The mechanisms by which alcohol exerts its carcinogenic effect have not been defined, because alcoholic beverages are complex mixtures, but ethanol is known to be the predominant agent responsible for carcinogenesis. A recent population study of the ‘Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption’, published in The Lancet (July 2021), notes several biological pathways by which the consumption of alcohol, such as ethanol, can lead to cancer, including “DNA, protein, and lipid alterations or damage by acetaldehyde, the carcinogenic metabolite of ethanol; oxidative stress; and alterations to the regulation of hormones such as oestrogens and androgens.”

Epidemiology

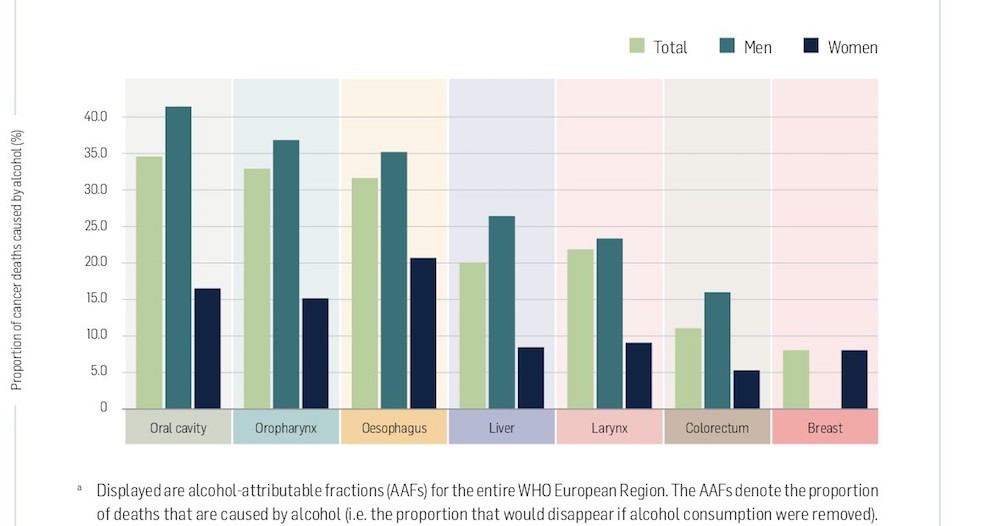

The risks vary by cancer type: the proportion of deaths accounted for by alcohol is higher for cancers of the head and neck than for any other type of cancer, but in terms of overall deaths, the biggest toll is in breast cancer.

Proportion of cancer deaths, per cancer type, that are attributable to alcohol (alcohol-attributable fractions), by sex, 2018

As the WHO points out in its 2020 briefing on Alcohol and cancer in the WHO European region: “all types of alcoholic beverages, including beer, wine and spirits, are linked to cancer, regardless of their quality and price,” with the risks of developing cancer increasing “substantially” the more alcohol is consumed. No level of consumption is entirely safe, it emphasises, with the equivalent of just a single glass of wine a day estimated to have accounted for more than 4,600 breast cancer cases in women in the WHO European Region in 2018.

According to the Lancet Global burden study, of almost 750,000 alcohol-attributed cases of cancer diagnosed worldwide in 2020, ‘moderate’ alcohol consumption (less than 20g per day) accounted for 103,100 cases (14%), ‘risky’ consumption (between 20 and 60g per day) accounted for almost 291,800 cases (40%) and ‘heavy’ consumption (more than 60g per day) accounted for around 346 400 (47%).

Alcohol and Europe – different cultures, different policies

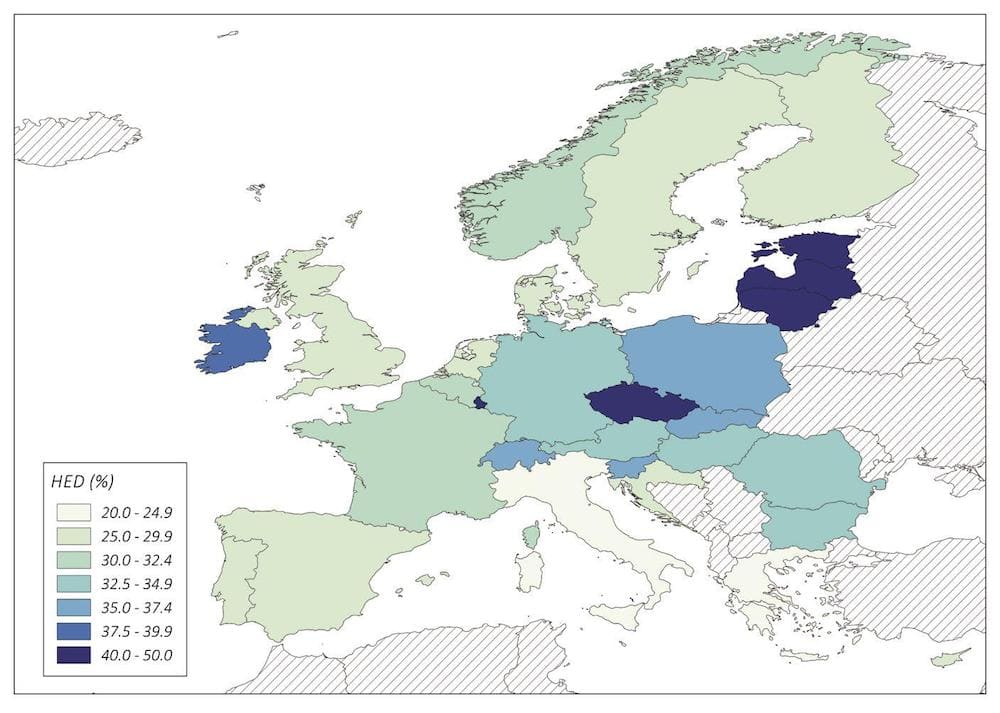

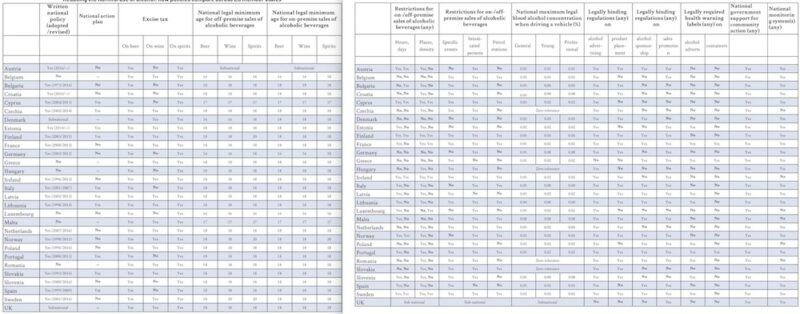

What we drink, how much we drink, and drinking patterns vary across Europe, as do policies and regulations designed to control the use of alcohol. In general, for instance, ‘binge drinking’ episodes (heavy episodic drinking) are more common in Northern European countries, while Mediterranean countries drink more wine with their meals. Different countries make different use of various policy options for controlling alcohol consumption, such as excise tax, restrictions on advertising, age limits, limits on where or when alcohol can be purchased, and drink driving legislation.

Prevalence of ‘heavy episodic drinking’ (HED). Percentage of adults with at least one occasion of a minimum intake of 60g pure alcohol ‘in past 30 days’ in EU+ countries, 2016

Reducing the harmful use of alcohol: how policies compare across EU member states

If EU member states are to achieve the goal set down in Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan to reduce harmful use of alcohol by at least 10%, they will need to assess and build on their existing policies and work out the most effective way to change existing drinking cultures for the better. While there can be no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution, member states can certainly learn from each other’s experiences ‒ both bad and good.

Below, we look at the experience of three countries: Lithuania, the country with the highest per capita consumption in the EU, Slovakia, where alcohol consumption is around average for the EU, and Italy, which per capita drinks less than any other EU member state.

Notable differences between the countries, as documented in the comprehensive WHO Global status report on alcohol and health 2018, include what is drunk, and patterns of drinking. In Italy, wine accounts for 65% of all alcohol consumed, while in Lithuania it accounts for a mere 7% and in Slovakia 21%. Spirits, by contrast, account for only 10% of alcohol consumption in Italy, compared with 37% in Lithuania and 42% in Slovakia.

Episodes of binge drinking are also more rare in Italy, where, in 2016, 37% of men and 8% of women reported drinking the equivalent of at least 60 grams of pure alcohol “on at least one occasion in the past 30 days”. This compared with 71% for men and 32% for women in Lithuania and 56% of men and 18% of women in Slovakia.

Lithuania: a roller coaster ride

Lithuania is not only one of the countries with the highest alcohol consumption, but also a country where the benefits associated with controlling alcohol consumption can best be observed. Consumption indicators have undergone dramatic changes with changes in its policies since Lithuania gained independence from the USSR.

Alcohol consumption was relatively low during Soviet times, due to a very restrictive anti-alcohol campaign launched in 1985. In 1990, when Lithuania declared its independence from the USSR, all foreign laws were banned. Accession to the European Union in 2004 resulted in a rise in disposable income, and this, combined with the very weak alcohol control policies, is seen as a major factor contributing to the rapid rise in alcohol consumption, which almost tripled from 5.56 litres of pure alcohol per person 1990 to 15.4 litres in 2010.

That rise was reflected in growing death rates from alcohol-attributed cancers, which by 2016 accounted for 280 deaths per 100,000 men and almost 135 per 100,000 among women.

In the last three decades, alcohol control policies have undergone a roller coaster in which there have been cycles of stricter control and stages in which consumption has been liberalised.

During the early ’90s, nearly all the alcohol control laws vanished. There was no regulation of production, import or sale of alcohol until 1995. The Alcohol Control Law, the main policy document, was adopted that year. But 63 amendments came into effect between 1995 and 2020, making it the most frequently reformed act in Lithuanian democratic history.

“Let’s say alcohol consumption was a well-developed culture,” says Mindaugas Štelemekas, from the Health Research Institute of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. “The very first law prohibited home-brewed alcohol beverages, but not those naturally fermented below 18% [alcohol by volume] and 9.5% in the case of beer,” he says. Sales were restricted to people over 18 years old and were forbidden for intoxicated people and uniformed officers. Sales of alcoholic drinks were also banned in healthcare, education or sports facilities, shops selling stuff for children, petrol stations and vending machines.

The foundation of all future changes in alcohol policy came with a norm criminalising drink-driving in 2000, says Štelemekas. But a year after, an amendment came into effect allowing alcohol to be sold in petrol stations. It was not banned again until 2016, when Lithuania renewed its commitment to alcohol control, with the establishment of the State Fund for Public Health Promotion. Alcohol consumption in that year was 15 litres per capita ‒ almost triple the level for 1995 ‒ and accounted for approximately 7.6% of total deaths in Lithuania. This was the first time community action toward alcohol prevention harm was publicly supported, says Štelemekas.

The first real demonstration of political commitment to alcohol control had come almost a decade earlier, in 2008, which was declared the ‘Year of Sobriety’. But it wasn’t until the end of 2018 that the country adopted its National Programme for Drug, Tobacco, and Alcohol Control and Prevention 2018‒2028, which for the first time developed a public health response, with the perspective of a decade.

The legal minimum age to purchase alcohol was increased to 20 years and retail hours were reduced from 10 am until 8 pm on Mondays to Saturdays, and from 10 am to 3 pm on Sundays, “[though] we still have a huge problem with people going drunk to work on Monday morning,” Štelemekas comments.

Štelemekas contributed to an expert review of the Lithuanian Alcohol Control Legislation between 1990 and 2020, which was published in 2020, in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, with the aim of informing effective policies going forward.

“The main problem is that the alcohol control policy in Lithuania focuses on laws, rather than documents developed by experts”

“The development of alcohol control policy in Lithuania reflects the complexity confronting decision-makers in balancing the economic and public health interests,” he says, and he argues strongly in favour of investing in and listening to expert advice to inform policy making. “The main problem is that the alcohol control policy in Lithuania focuses on laws, rather than documents developed by experts,” he says.

There are signs that this approach may now be changing. The most recent amendments to alcohol control laws came about through a transparent and democratic parliamentary process, which Štelemekas sees as a welcome sign that his country is going in the right direction.

Slovakia: targeting adolescent drinking

Slovakia has a mix of two diverse cultures regarding alcohol consumption. It has many vine growing areas, where wine is part of daily life, as it is in Mediterranean countries. But at the same time, the consumption of spirits is quite high, and often results in intoxication, according to a 2011 study on alcohol-related mortality in regions in Slovakia.

In contrast to Lithuania, alcohol consumption in the country has been slowly decreasing since the ‘Velvet Revolution’ took the country (then part of Czechoslovakia) out of the USSR in 1989. It remains relatively high, however, at 10.4 litres per capita per year in 2016 (compared with 13.8 in Lithuania, and 7.1 in Italy, the same year). The incidence of alcohol-related cancer deaths is the highest of the three countries, with 305.9 deaths per 100,000 men, and 155.8 for women.

Studies agree that the rate of unemployment has a lot to do with the high rates of alcohol consumption and the related mortality. Until 1989 the unemployment rate was almost zero, but it rose to a peak of 16% in 1998, before dropping back to around 8% in 2007, and then rising again to almost 13% in the wake of the global financial crisis.

In 2008 the Slovakian parliament passed the Act on the Protection from Alcohol Abuse and Establishment and Operation of Detoxification Centres. This was reinforced the following year, to strengthen provisions on under-age drinking, with measures banning people aged under 15 from public places that serve alcoholic drinks after 9 pm, unless accompanied by their legitimate guardians.

The effectiveness of this approach was questioned in a 2011 study conducted by public health experts from Slovakia, Belgium and the Netherlands. “In the Slovak Republic, unlike the legislative steps taken in recent years leading to a restriction on smoking in public and to a health protection of non-smokers, the field of alcohol consumption still lacks effective actions which would have a positive impact on the health of inhabitants,” wrote the authors. They recommended greater use of price deterrents: “as alcohol is cheaper than soft drinks, politicians should consider the tax instrument to be used in the fight against avoidable alcohol-related mortality.”

In 2013, local municipalities were given powers to add places where the selling of alcohol was prohibited to those defined at the national level, such as healthcare premises or education centres.

This was the year that Slovakia first approved an official alcohol control policy based on the approach recommended by the WHO, which sees it as a public health priority. The policy aimed to promote activities to reduce social tolerance toward alcohol consumption, especially among younger people.

A further significant amendment, in 2018, explicitly banned drinking under the age of 18, strengthening existing regulations that banned selling to and serving this age group. This was an important step, because access to alcohol among adolescents was, and remains, a significant issue, according to a 2021 study that looked specifically at ‘Alcohol Use and Its Affordability in Adolescents in Slovakia between 2010 and 2018’.

The study found that, among 15-year-old schoolchildren, more than one in five boys and more than one in ten girls admitted to having drunk alcohol at least once a week in 2017/2018. In an echo of the findings of the Lithuanian review, however, the authors, with backgrounds in medicine, healthcare and social work, flag up the limitations of relying too heavily on legislation to control alcohol consumption.

“The impact of measures to control adolescent drinking is affected by the prevalence of drinking among adults, family influences, and peer pressure”

They note that, while control measures focused on adolescents play a crucial role in preventing the health and social impact of excessive alcohol use, “their impact is significantly mediated by an overall social environment, namely prevalence of drinking among the general adult population, together with culturally/historically based drinking patterns, family influences, and peer pressure”. Nowadays, they conclude, preventive measures still have a “relatively weak effect”.

Italy: changing the drinking culture

Mediterranean countries have done well in reducing alcohol consumption over the past three decades. The success has been particularly marked in Italy, where per capita consumption decreased from 12.4 litres in 1990 to 7.6 litres in 2014. It is reflected in rates of death from alcohol-attributed cancers that are one-third lower than the equivalent rates in Slovakia for men, at just over 190 cases per 100,000, and around a quarter lower for women, at around 120 per 100,000 (2016 data).

The key to the country’s relative success in reducing alcohol consumption compared to the rest of the European Union is widely seen to lie in early adoption of a paradigm shift towards treating alcohol as a central issue in the national health strategy.

Prevention has been at the core of every programme linked to alcohol abuse in Italy since 1998. By 2000 it had reached its two main targets: to reduce by 20% the prevalence of male and female drinkers consuming respectively more than 40g and 20g alcohol a day, and to reduce by 30% the prevalence of drinkers consuming alcohol between meals. The fact that wine is the most widely preferred drink for Italians is a sign that they drink alcohol mainly while eating.

The key to the Italy’s success lies in its early paradigm shift towards treating alcohol as a central issue in the national health strategy

Italy followed recommendations from international institutions, such as the WHO’s European alcohol action plan reduce harmful use of alcohol and the WHO Declaration on Young People and Alcohol in drawing up its National Health Plans ‒ national public health plans agreed with regional authorities every three years, which were first introduced in 1994. The approach is multidimensional ‒ a combination of actions in different areas such as information, drink driving, legislation or advertising. Crucially, it includes monitoring, reporting and dissemination in its core strategies.

To monitor success in meeting health targets, in 2000 Italy defined key indicators. Experts advised that ‘per capita’ alcohol consumption was a poor metric, because it reflects overall alcohol sales, and does not identify the distribution of consumption among individuals and the related patterns of consumption. The ‘per capita’ metric was therefore substituted by ‘prevalence and trends’ in daily alcohol consumption, alcoholic beverages consumption between meals, and crude quantities.

This enabled the system to better identify people who were exposed to alcohol as a risk factor. Monitoring trends with year on year data also helped to put alcohol consumption on the political and public agenda. Public awareness campaigns have been running since 2001, when Italy designated April as Alcohol Awareness Month. The Ministry of Health supports a coordinated effort that brings together national, regional and local governments along with NGOs, media, and civil society.

Having done the right things early, Italy is now ahead of the game. Emanuele Scafato, Director of the WHO’s Centre for Research and Health Promotion on Alcohol-Related Issues, and part of the Italian National Institute of Health, says, “In the last years, we got to the next step: a change of behaviour. Even the industry understood that drinking less was an important target to reach. And the consumers moved, and especially the younger generation, to a healthier lifestyle.” Marketing communication evolved towards depicting drinking behaviours that project moderation and responsibility. The most recent Commercial Communication on Self Regulation, from 2017, strengthened the stipulation that marketing must not encourage uncontrolled consumption. Guidelines specify, among other things, that marketing messages may not depict alcohol as a solution to personal problems or as a means to promote clear thinking or enhance sexual performance. Any implication that not consuming alcohol indicates social inferiority is also counter to the guidelines.

“I want to provide all the arguments so people can choose with valid information. And health is a choice”

In contrast to Lithuania and Slovakia, the Italian approach is not heavily reliant on regulation, though policy measures do include a minimum purchase age of 18 years or vending regulations that prohibit shops from selling alcoholic drinks between 9 pm and 2 am in most municipalities. “I will never tell someone not to drink, but I want to provide all the arguments so people can choose with valid information. And health is a choice,” says Scafato.

How can Europe do better?

As the recent Lancet population study of the ‘Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption’ concludes, “alcohol use causes a substantial burden of cancer, a burden that could potentially be avoided through cost-effective policy and interventions to increase awareness of the risk of alcohol and decrease overall alcohol consumption.” The authors recommend strategies such as those included in the WHO’s ‘best buys’ for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: reduction of availability, increase in price via taxation, and a ban on marketing.

Speaking to Cancer World, a spokesperson for the European Commission stresses that alcohol-related harm is a major public health concern in the EU. “This is why we are including a clear target to achieve a relative reduction of at least 10% in the harmful use of alcohol by 2025, a target also supported by the WHO.”

Given that, between 2010 and 2016, the European Union achieved only a 1.5% reduction in total alcohol consumption, the target of a 10% reduction in harmful use over the coming five years might be seen as a suitably ambitious one. Nonetheless, it would still stop woefully short of achieving average per capita alcohol consumption rates in line with the 20g/day used in the Lancet study, for instance, to define ‘moderate’ as opposed to ‘risky’ or ‘heavy’ drinking.

Using the WHO 2016 data for the average per capita consumption among drinkers in 30 EU+ countries of 15.7 litres of pure alcohol a year ‒ which translates to approximately 33g a day ‒ a 10% decrease would reduce average consumption to 29.7g/day. That average, however, disguises major gender disparities, with the average per capita daily consumption among male drinkers estimated closer to 22 litres per year, or 47g per day. A 10% drop would only reduce this to 42.3g/day, more than twice the limit defined as ‘risky’ in the Lancet study. It also disguises major disparities between member states. While male drinkers in Italy average 16.5 litres a year (35 g/day), the equivalent figure for Lithuania is 27.9 litres/year or 60g/day, which with a 10% reduction would fall to 56g/day.

Asked about strategies to reach that 10% target, the European Commission spokesperson acknowledged that policies to tackle harmful alcohol consumption “are complex and require trade-offs.” She stressed the value of learning from past experiences across the EU, building on the work done by the Steering Group on Health Promotion and Prevention ‒ a Committee with representatives from health ministries of the different member states which, in 2020, identified 16 best practices. “One of them specifically targets alcohol consumption, while others promote a generally healthy lifestyle and so indirectly prevent addictions too.” Some of these best practices, “selected with the involvement of the Steering Group,” will be co-funded in 2021 and 2022 under the new EU4Health Programme, she says.

Emanuele Scafato believes member states could do well to follow the lead of Italy, with a strong focus on educating and convincing populations to change the whole culture around drinking. All EU health ministries are aware that alcohol is related to cancer, but there is no such awareness among citizens, he says. He argues for much greater urgency in collecting data to understand perceptions and consumptions patterns, and then developing and applying the best communications strategy tailored to each situation.