Six years ago, Mada accompanied her daughter to the gynaecologist for an early pregnancy scan. Whilst she was there, the physician suggested Mada herself get a check-up.

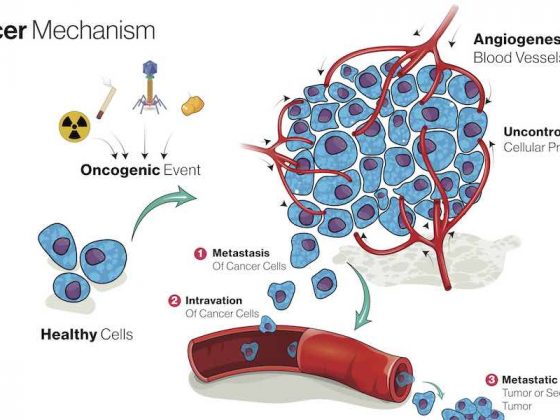

“The doctor at first thought I had a very large cyst on my ovary,” Mada recalls. “They later found out it was not a cyst, but that the ovary was swollen, and I had a tumour.”

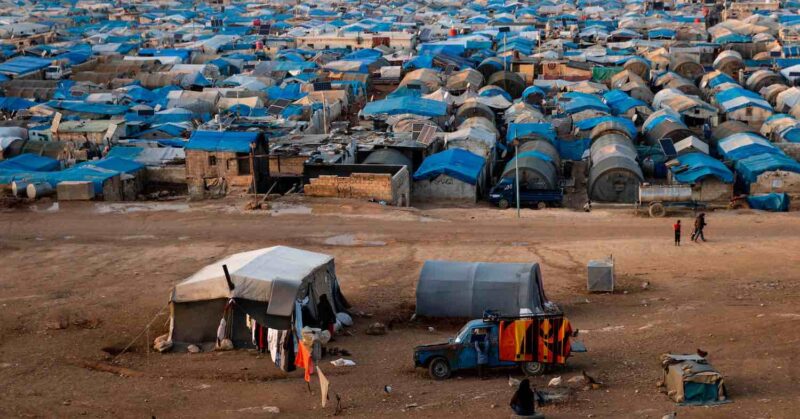

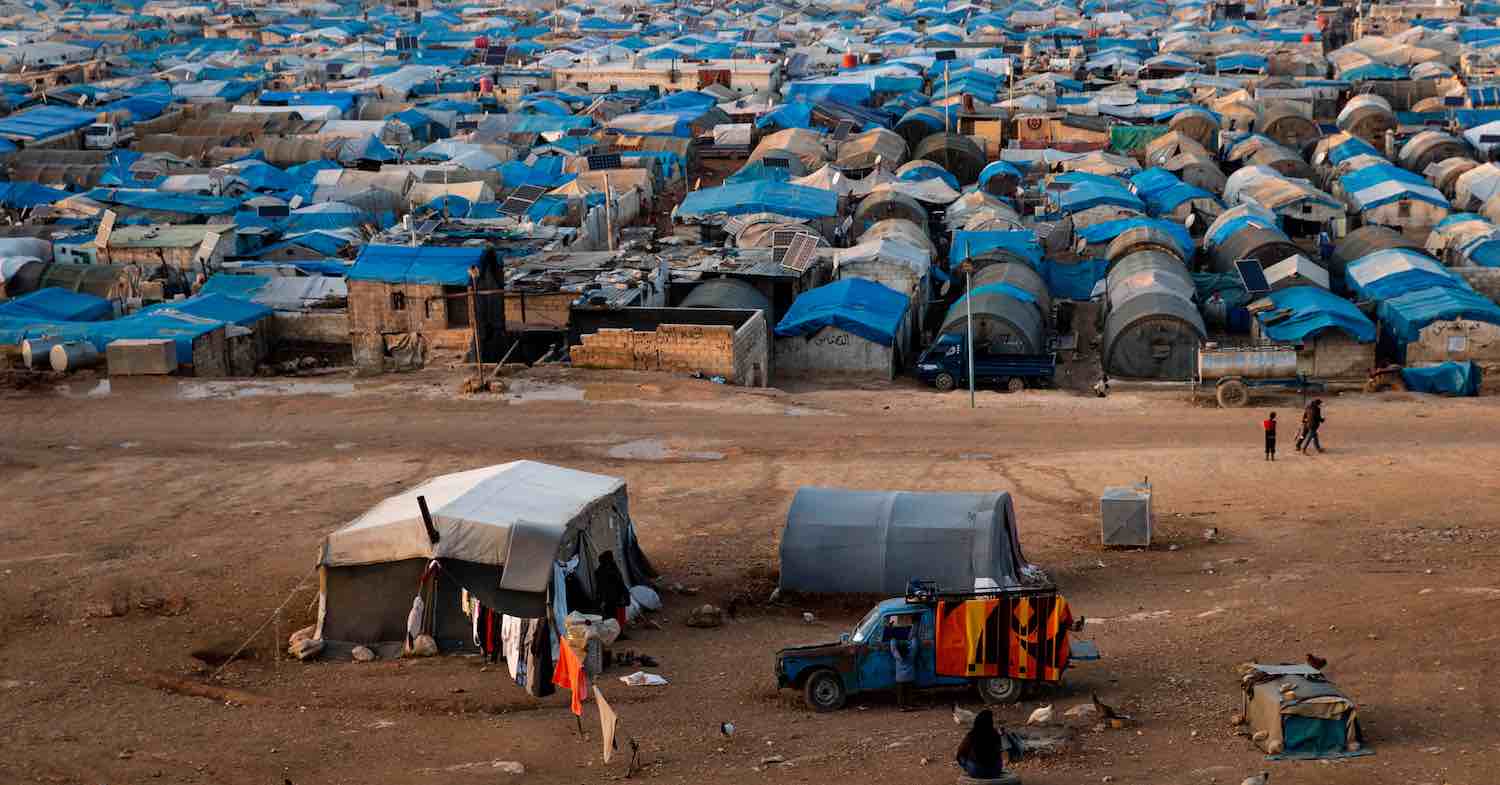

Mada is from Idlib in the northwest of Syria, home to almost 2 million people who were displaced from across the rest of the country, as the 11-year war razed thousands of homes to the ground and forced families to flee.

That lengthy civil war also devastated the healthcare system, including cancer care. “Radiotherapy is non-existent, chemotherapy is variable and cancer surgery is impossible,” says Richard Sullivan, Professor of Cancer and Global Health at King’s College London. “And there is no systematic data on what is happening in northwest and northeast Syria.”

So Mada crossed through the Syrian side of the Bab Al-Hawa border crossing and made her way to the Al-Amal Centre in Gaziantep, Turkey, where she stayed for nine months whilst undergoing chemotherapy at a Turkish state hospital.

With this, Mada became one of 9,000 cancer patients to be treated with the help of Al-Amal since it opened its doors in 2013 to help ensure access to cancer care for the millions of Syrians living in Turkish controlled northern Syria and as refugees within the borders of Turkey.

A novel approach to cancer care in a conflict zone

Al-Amal – ‘Hope’ – is a not-for-profit humanitarian organisation that was established to address an urgent problem that the European cancer community has become all too familiar with since the invasion of Ukraine: how to ensure that cancer patients in conflict zones get access to the treatment and care they need.

In the decade that has passed since the start of Syria’s civil war, however, the challenge has morphed into something requiring a more long-term holistic approach. Control along Syria’s northern border remains contested and split between various players, with Turkey – by agreement – controlling a region in the northwest covering a population of around 4.5 million Syrians. A further 3.7 million Syrians are still refugees within Turkey.

Al Amal, which serves Syrian populations in both northern Syria and Turkey, is taking on some cancer control responsibilities for these populations that would normally be fulfilled by a state health service. These include providing prevention and early detection services – awareness, screening – that are the cornerstones of tackling cancer.

It’s evolved into an impressive operation, as Abdulrahman Alzinou, Chairman of Al-Amal explains. “Now, the Al-Amal Association is considered a primary party that plays the state’s role in northern Syria, serving many people, more than, for example, a population of a country such as Qatar,” says. “We play the role of a government agency but with minimal international support. Our most important priority now is the prevention and early detection of the disease. We are trying to intensify our efforts on awareness, education and early detection because these things save hundreds of patients and relieve us of the burden of treatments.”

Al-Amal operates a clinic in Akhtarin, in northwest Syria, staffed with a range of oncology professionals and equipped to deliver screening and diagnostic services and some cancer treatments and care. Support from the Turkish healthcare services remains an essential component, however. The organisation has a formal agreement with the Turkish Ministry of Health that gives them a pathway to refer people from northern Syria, like Mada, for cancer treatment in Turkish hospitals – though that pathway is becoming increasingly precarious. It also has four centres in the Turkish cities of Antakya, Gaziantep, Adana, and Ankara, which care for patients before and after they undergo surgery and chemotherapy in Turkish hospitals, providing accommodation and professional psychological support.

Efforts to raise awareness about cancer risks and prevention, and the importance of early detection and attending screening, depend heavily on teams of volunteers, who work in the refugee camps on both sides of the border, delivering leaflets, lectures and seminars. Two mobile clinics, based 30‒40 km either side of the Akhtarin centre, visit population centres in the Idlib region, spreading the word about prevention, and offering diagnostic services including mammography, ultrasound and essential lab tests.

The Al-Amal mobile clinics

On the back of a converted lorry, a strip of posters provides general health advice, including on cancer prevention: no smoking, it warns, and no prolonged exposure to sunlight. To the side of the van, a group of women gather with their children under an awning. They are waiting to enter the lorry – Al-Amal’s mobile clinic – which comes with a mammography unit, ultrasound equipment, a basic pathology lab and clinical, imaging and pathology diagnostic specialists.

“In the north of Syria, we discover about 100 cases per month,” says Kheder Diri, an endocrinologist who works at the clinic. Diri is from Daraa, a city in the southwest of Syria, close to the Jordanian border, known as the ‘cradle of the revolution,’ as it’s where Syria’s Arab Spring protests began after a group of young students were tortured for scrawling anti-government graffiti on a wall.

Diri singles out childhood leukaemia ‒ now curable in 9 out of 10 children with access to high-quality care – as one of the big cancer killers in the northwest region. “There is a high percentage of leukaemia in children. These numbers did not exist before the war. The situation was much better.

“Treatment was provided free of charge, and there was a large, well-equipped hospital in Damascus for cancer that provided all services, including treatment, diagnosis, follow-up, and operations. But now the situation is very difficult,” he says. He adds that cases of kidney cancer have also risen, which he puts down to the polluted water in the refugee camps. “These cases were very few before the war.”

Even pre-conflict there was little early diagnosis, however, especially for poor people or women, says Sullivan: “There was just not that health literacy and outreach that we have in many other countries.”

Broken pathways, fatal delays

Organising screening and treatment for cancer is complicated enough within a functioning state, where citizens are signed up with a GP and can be referred for treatment immediately if something is detected. Delivering all that within a conflict zone is a huge challenge, says Sullivan, who talks about ‘unique therapeutic geographies’ that can change rapidly and be hard to predict.

“Patients move around all over the place, pathways which work for a while and then get stopped, it may be stopped because of security reasons, or because of financial reasons. So it makes it incredibly hard to do any form of top down planning.”

“If you’re displaced or you’re a refugee, your greatest enemy when it comes to cancer is time”

Despite the formal agreement with the Turkish health authorities, referral pathways for northern Syrians diagnosed with cancer are far from quick or easy. “I would like to highlight that some tumours begin as small masses, and while waiting for Turkish approval to obtain permission for the patient to enter Turkey for a period of two months, the tumour grows and becomes more complex,” says Diri. “Time is a very important factor for cancer patients.”

“You’re picked up with stage two and by the time you get treated you are stage four,” agrees Sullivan. “This is the brutal reality. The more data we’re collecting, the more we realise this is what’s going on. So, time is against people. I think what I say to people is, if you’re displaced, or you’re an IDP [internally displaced person], or you’re a refugee, your greatest enemy when it comes to cancer is time.”

Meeting the costs of cancer

Three years ago, Inoud El-Hussein’s five-year-old son, Abdrabbo, was misdiagnosed with multiple sclerosis, which eventually turned out to be leukaemia. She packed her bags, left her six other children in Syria with her husband and travelled to Turkey with her son. Neither of them had a passport.

Once in Turkey, Abdrabbo was transferred to Adana hospital where he received chemotherapy. Al-Amal provided the accommodation, food, transport, medicine, and a translator. “I couldn’t have afforded to stay in Turkey without Al-Amal’s help,” says El-Hussain. “If we had stayed in Syria without medication, he wouldn’t have made it until now.”

This story underscores another challenge that Al-Amal and their patients face – money. The cost of cancer care is $12,000-$13,000 per patient, says Sullivan, and what’s worse, the more advanced the stage, the more expensive the care is. “The rule of thumb is that it quadruples between stage one and stage four.”

“Continuing to foot the bill for Syrian patients is becoming an increasingly contentious issue within Turkey”

For the first seven years after it was established, Al-Amal was doing well. Women turned up for their screenings, people in the camps responded to the lectures, and Turkey – along with many neighbouring countries – was generous in absorbing referrals into their state hospitals. However, with the lack of any planning or budget for cancer treatment coming from the UN bodies or international health organisations with responsibility for displaced populations, continuing to foot the bill for Syrian patients is becoming an increasingly contentious issue within Turkey. Al-Amal is increasingly having to step in to help patients fund their treatment.

“The bottom line is that the budget impacts are quite massive per annum if you are hosting refugees in the country. And so what we saw over time is, right at the beginning you saw by and large most people not having to pay for anything,” explains Sullivan. “And as the years have been going on, more and more people are now being asked to pay for their care, or they’re given free surgery but then told you have to pay for chemotherapy, or they’re told you have to pay for your diagnostics but will operate on you for free.”

Then the coronavirus pandemic hit. Healthcare systems around the world faced the most serious of challenges. As the focus fell firmly on mitigating the effects of the virus, the EU limited support to Syrian refugees and it became harder and harder to secure treatment inside Turkey.

“More than 300 patients died because they could not be treated,” says Al-Amal’s Alzinou. “We appealed to the Turkish government and met with officials from the Turkish Ministry of Health, who allowed us to use the hospitals again for free if the medicine was in the hospital. Still, mostly now, the patient is obliged to provide his or her own medicine to the hospital at their own expense.”

Some of them were able to do so for a while, he says, but others could not afford it and returned to Syria. “Some of them died. We now have more than 1,200 cancer patients on the waiting list who need cancer medicine unsubsidised by the Turkish government or the European Union.”

Supplying cancer therapies

Imatinib is delivered to a young leukaemia patient living in a refugee camp in Idlib. This child will need a monthly supply of the drug for the foreseeable future, so Al-Amal runs a ‘sponsor a cancer patient’ programme to ensure she gets it. The organisation relies heavily on sourcing generic drugs like this one to keep costs down. Turkish hospitals were generous for many years in covering treatment costs, but popular support for shouldering that burden is waning, particularly with the ending of EU funding and the pressures of the Covid pandemic.

As Turkey approaches elections next year, at the forefront of the agenda is refugees. Roughly 3.7 million Syrian refugees live in Turkey, and anti-refugee sentiment is on the rise, propelled by a severe economic crisis which has sent the lira crashing and inflation to an all-time high.

“Once socio-political sentiment changes against refugees, you have a problem, because it makes it very difficult for the hospitals to operate, because they’re under political pressure,” says Sullivan. “It makes it very difficult for anyone to speak honestly about issues and deal with problems and referral pathways. It makes it very difficult to collect data and do intelligent planning, because nobody wants to collect the data.”

“Popular pressure on the Turkish government may affect the support and treatment of patients, especially at this critical stage before the elections,” adds Alzinou. “Most cancer patients and some incurable cases are buying medicine at their own expense.”

A model for when state and aid institutions fail?

With the EU limiting support, no funding from UNHCR (the UN body with responsibility for refugees), and a swell of right-wing sentiment across Europe, Syrian refugees have been pushed down the priority list.

“Groups like Al-Amal are going to be essential for as long as we can see,” says Sullivan. “They’re the only organisation that can adapt rapidly to a situation and without them there’s zero hope. The problem is that what you need to address this is a highly organised, highly centralised referral system that can move really quickly. No one’s willing to invest. No one’s willing to give up power, no one’s willing to be transparent about what they can and can’t do.

“So the next best thing you can get is these patient-driven organisations that have the political and social connections, know how to navigate these rapidly changing therapeutic geographies and basically do all the heavy lifting for patients around accommodation and transport. I’ve seen no other model in the world that can do that, apart from the golden model which is something organised through a UN system or a very, very large NGO like the International Committee of the Red Cross.”

Al-Amal has tried to turn their association into a model for other countries struggling to provide cancer care to patients in a war-torn environment, including in Yemen, but with little success. “We offered the Yemenis to do the same project for them,” says Alzinou, “focusing on prevention, awareness, early detection, and securing some cheap medicines, such as the Indian ones. We have been using Indian drugs for three years, and they were effective and are much more affordable, ten times cheaper. But the project was not completed because no organisations were ready to do this task. But we are prepared to transfer the experience to any country in need.”

“It’s entirely context dependent,” says Sullivan. “In a sense, Syrian refugees are lucky because they have Turkey. Turkey has pretty much fully transitioned, high income services, systems, and it’s right on their doorstep. They also have an extraordinarily proficient, well-governed cancer care workforce. By and large you don’t see much predatory activity going on.”

Lucky compared with Yemenis needing cancer care, maybe. But in a worse position by far than those caught up in a conflict in Ukraine. Unlike on the Syria-Turkey route, there are no delays for cancer patients leaving the country to seek help. Ukraine is surrounded by countries with money and power, says Sullivan, and there is a wealth of funding for patient organisations, medicine and industry. While it was somewhat chaotic in the first four months of the Russian invasion, now the system works well and patients easily move across borders.

“Somebody got to Moldova, to Chisanau, and they were immediately diagnosed, and it was stage 2 breast cancer, but they had no way to treat them there because they haven’t got the technology. And a day and a bit later they were at Cluj, the Romanian cancer centre, being treated. That’s how fast these organisations work. Why? They have money, power, and easy access across borders. So in a sense it’s the same model but it’s all about context.”

“The outstanding operational results are due to patient organisations adapting very quickly to the needs on the ground and working between the patient and the care provider,” he adds. “Exactly what Al-Amal do. So what they’re doing essentially is adaptive behaviour. In the world of conflict that is quite a normative thing to do, because of the way these therapeutic geographies change so much.”

Source: Al Amal

One of the many tragedies of the situation, as Alzinou points out, is that Syria, before the conflict, was considered one of the pioneering countries in the region in the treatment of cancers, and people had access to care. “Syrian doctors and hospitals used to provide cancer services for free and with a high cure rate.” The country had one of the largest specialist facilities in the region for manufacturing chemotherapies, but sanctions have set back much of that work, he says.

Also disrupted was the ability to monitor trends in cancer incidence, but from their own experience, Diri’s team of oncologists believe rates of cancer have risen since the start of the war, and they blame it on environmental factors that may have a specific link to cancer, or may work through more general impacts on people’s health. “The numbers increased because of the living conditions, because of the chemical weapons and toxic gases used against civilians. The migration, deportation, lack of nutrition and instability, lack of hygiene, pollution, the burning of tyres, plastic shoes, rubbish, and papers to create heat in winter. All of this led to weak immunity,” says Diri.

It will take a lasting political solution to address these many problems. But in the meantime, four days a week, Diri and his colleagues in Al-Amal’s medical team set off in their mobile clinic and drive around the neighbourhoods of Al-Bab, a city 40 kilometres northeast of Aleppo, and the surrounding villages, seeing up to 35 patients a day, relentlessly screening for cancer among the population.

Al-Amal

Al-Amal is a not-for-profit organisation that provides prevention, screening and diagnostic services for a population of around two million in parts of northwestern Syria currently under Turkish control and for the estimated 3.7 million Syrian refugees still in Turkey.

Al-Amal is a not-for-profit organisation that provides prevention, screening and diagnostic services for a population of around two million in parts of northwestern Syria currently under Turkish control and for the estimated 3.7 million Syrian refugees still in Turkey.

It has two mobile clinics equipped with diagnostic and screening facilities.

It employs 60 full-time staff, including specialists in oncology, haematology, internal medicine, gynaecology, gastroenterology, and paediatric oncology, as well as a team of specialist nurses, psychological support staff and administrators.

It has capacity to carry out certain treatments, and can refer patients to Turkish hospitals, by agreement with the Turkish ministry of health, though referrals can take time and costs are often not covered.

It runs one health centre in northern Syria, and four centres in Turkey – in Antakya, Gaziantep, Adana and Ankara – which care for patients before and after they undergo surgery and chemotherapy in Turkish hospitals. The centres serve around 180 patients every day.

Since 2013 it has served around 9,000 cancer patients.

Education and awareness activities are conducted mainly by volunteers.

Funding relies on donations, which have become harder to secure since the Covid pandemic. Current major partners include Qatar Charity, the World Assembly of Muslim Youth, and the Kuwaiti Tanmia Association.

The image shows delivery of financial assistance to the family of a cancer patient living in Maarrat Misrin refugee camp in the Idlib region. Source: Al-Amal

Amelia Smith contributed to this report

1 comment

Thanks alot for Alamal assosiation that delivered the voice of patients,and serve,and dedicated supporting womans,children,and elderly faithfully

Comments are closed.