Opioid analgesics are essential for pain relief and pain treatment in patients with active malignant disease. Yet, in 2011, the World Health Organization estimated that, worldwide, 5.5 million people living with terminal cancer suffered from moderate to severe pain, because of inadequate access to controlled medicines (Vranken et al., 2016). Since that time, the consumption of opioid analgesics has increased globally, particularly in western countries, including western and central Europe. But access remains a problem in some countries and can be very patchy within countries, particularly where national pain and palliation services are underdeveloped or nonexistent. Many GPs and oncologists remain reluctant to prescribe opioids, and many patients remain resistant to taking them, despite strong evidence of their safety and benefit and authoritative guidelines on how they should be used. As a result, unnecessary suffering caused by poorly controlled cancer-related pain continues to be a problem.

“Pain relief is a fundamental human right”, emphasizes Tomasz Dzierżanowski, Vice-President of the Polish Society of Palliative Medicine. Dzierżanowski, whose day job is Assistant Professor at the Laboratory of Palliative Medicine at the Medical University of Warsaw, has been tracking the availability and accessibility of opioid analgesics in Poland since 2000. Over the past 20 years, per capita consumption has increased in Poland by more than four-fold, rising steadily from 36 mg oral morphine equivalents (OME) in 2000 to 103.4 mg in 2015, with the (as yet unpublished) figures for 2020 showing a further rise to 150 mg. The latest indication is that consumption levels were stable in Poland from 2018 to 2020. “All strong opioids are now available in Poland, with the exception of hydromorphone,” says Dzierżanowski.

A big change in opioid prescribing patterns was brought about two years ago when bureaucratic procedures involving special prescription forms for opioids were replaced by a mandatory electronic prescription system. Prior to that, the growth in opioid consumptions had been accounted for largely by fentanyl patches and, later also by buprenorphine, which in 2007 was approved as the only strong opioid available on regular prescription forms. “Every physician in Poland is [now] allowed to prescribe all available opioids, so this is no longer a barrier,” says Dzierżanowski, though buprenorphine and fentanyl transdermal formulations remain the most frequently used strong opioids in Poland, in terms of OME.

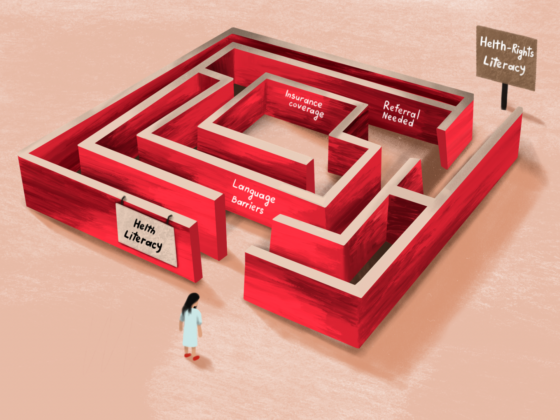

Regulation is no longer the main obstacle

Dzierżanowski sees the reduction in red tape involved in prescribing opioid analgesics as an important step in making available suitable analgesics for people suffering severe, and often chronic, pain. But other barriers remain, he says, which need to be tackled. One of them is anxieties around use of opioids that stem in part from prejudice, but often from a lack of knowledge and confidence in how to use them safely. “The barriers now are opiophobia, and especially morphinophobia, which is a slightly different aspect, on both doctors’ and patients’ sides… and an insufficient working knowledge of the principles and guidelines for the treatment of cancer pain – I think these are the biggest impediments to optimal pain treatment,” he says.

Reimbursement regulations can also present an obstacle, he adds, as they are not always compatible with guidelines for pain relief in cancer patients. He cites the cases of tapentadol, which is only reimbursed when morphine appears ineffective – “An absurd situation, as tapentadol is a weaker opioid than morphine. So we need to accept that tapentadol is not reimbursed for most cases of cancer pain.”

“Lack of training and awareness of health professionals was most often mentioned as an impediment, followed by fear of addiction”

The Polish experience bears out observations made by the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) in its 2018 report. Taking a global perspective, the report states that: “Comparing the responses provided in 1995, 2010, 2014 and 2018, it is possible to observe a decrease in the number of times that onerous regulations are mentioned as impediments to availability.” Fear of addiction as an impediment, it notes, declined sharply between 1994 and 2014, but increased from 2014 to 2018. “Lack of training and awareness of health professionals was the factor most often mentioned as an impediment in both 2014 and 2018, followed by fear of addiction.”

Experiences in Serbia tell a similar story. Snežana Bošnjak is now Professor at the Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia and leader of its Supportive Oncology and Palliative Care Service. When she started work at the Institute, back in 1992, there was no such supportive service, and the situation regarding pain relief was dire: only tramadol and transdermal fentanyl were available for cancer patients in Serbia, and the country faced an acute shortage of oral morphine.

In 2006, Bošnjak was selected for an International Pain Policy Fellowship at the WHO Collaborating Center for Pain Policy and Palliative Care at the University of Wisconsin’s Carbone Cancer Center, which involved addressing regulatory barriers to cancer pain treatment with opioids. “When I started my fellowship, I needed to change laws and to change policies. For one physician, without any knowledge about policies, this was frightening, but also inspiring and challenging. It was quite a journey.”

“When I mentioned morphine, patients started to cry, because they associated morphine with end-of-life care”

By that time, however, she had already spent years trying to address patients’ unmet need for pain relief. “At the beginning, patients suffered in silence. They thought cancer must be painful and hesitated to report pain. When I mentioned morphine, patients started to cry, because they associated morphine with end-of-life care, with death,” Bošnjak recalls. “And there was no service to treat pain in patients who received anti-cancer treatment, only the management of cancer pain at the end of life was recognised.” In these years, Bošnjak worked to highlight the need of cancer patients to receive proper pain management during anti-cancer or antineoplastic therapy. “It was about bringing the patient experience into the focus, to ask cancer patients about pain and enable a service to respond to their needs for pain management.”

Improvements in Serbia were lauded by the INCB in its 2010 report.The Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia recognised the value of the consultations for hospitalised cancer patients experiencing pain by establishing a dedicated supportive and palliative care service, which now employs specialists from a wide range of disciplines to treat pain and other side effects of cancer and cancer treatment. This multidisciplinary approach is necessary, says Bošnjak, because pain is multidimensional, “but opioids treat only the somatic side of pain”. In addition to treating this somatic side, psychologists, social workers and a priest in the team also provide psychological, social and spiritual care for patients.

Thanks to her work with the International Pain Policy Fellowship, Serbia endorsed the medical use of opioids for treating pain in a new law on psychoactive-controlled substances and a new National Palliative Care Strategy was implemented that recognised opioids as essential for palliative care. This has been accompanied by a significant change in attitudes and knowledge among doctors and patients about the use of opioids as analgesics, says Bošnjak. “Now, in Serbia, the topic of pain is recognised. It is understood that cancer patients need proper management of pain, not only when they are at the end of their life, but throughout their journey, including survivorship. The system is now recognising the patients’ need.” All opioids recommended by the guidelines for treating cancer pain are currently available in Serbia and the right to relief of pain and suffering is recognised as a patient right she adds.

However, regional differences persist. The IORS where Bošnjak is practising, situated in the Serbian capital Belgrade, is an ESMO designated centre for integrated oncology and palliative care. The Supportive Oncology and Palliative Care Service treats every patient with cancer pain, and includes an acute Intensive Care Unit for intensive pain treatment, an outpatient service and a mobile consultation team. But not all cancer patients in Serbia benefit from this patient-centred, integrated care. “We would like to be a model for other cancer centres in Serbia, for them to recognise the need to integrate tumour-directed and patient-directed approaches in oncology. When these two approaches are integrated, patients live longer and better. The main focus now is to integrate these two approaches in all cancer centres.” Bošnjak’s wish is for other centres to also establish a service to respond in a timely manner to patients’ needs and provide help for cancer-induced symptoms and treatment-induced complications.

Fear of morphine persists

Nowadays, patients react differently when morphine is prescribed. “Morphine and other opioids are accepted as essential and effective pain medication,” she says, but adds that fear of morphine is still an issue: “They prefer when their analgesic is not called morphine.” Added to the perceived connection with end-of-life, she feels many patients are still afraid of becoming addicted. “Sometimes, they perceive morphine as so strong that you have to have very severe pain in order to get morphine. They don’t understand that morphine can be given for patients with moderate and severe pain, on the so-called second and third step of the analgesic ladder as per the guidelines.”

In Poland, Dzierżanowski experiences similar reactions. “When I say ‘morphine’, patients say ‘no, no, no, not morphine’. When we switch to oxycodone, that’s okay. Or fentanyl? which is 100 times more potent? That’s okay. But morphine – no.”

One reason he identified was the fear of respiratory depression caused by direct or indirect overdosing

Recently, Dzierżanowski surveyed the attitudes of palliative care specialists and other physicians towards opioids. “In palliative care, we don’t have opiophobia on the doctors’ side. But other specialists hesitate to prescribe opioids.” One reason he identified was the fear of respiratory depression caused by direct or indirect overdosing. “That said, morphine also brings the connotation of drug dependence, and doctors do not want to produce drug dependency in their patients.”

Building knowledge and confidence

Bošnjak and Dzierżanowski both see raising awareness and promoting education about opioids’ role in pain management – among both healthcare specialists and patients ‒ as an important element in improving pain control, together with expanding palliative care services. “We need postgraduate, continuing medical education programmes on pain treatment,” emphasises Dzierżanowski.

“Most regular doctors do not know those guidelines. We need them free-of-charge, translated and disseminated by local organisations”

Although ESMO and NCCN have published guidelines for treating cancer patients who experience pain, these international guidelines remain inaccessible for many doctors, Dzierżanowski adds. “Most regular doctors do not know those guidelines, that they exist or what they mean. We need them free-of-charge, available to everybody, translated and disseminated by local organisations – otherwise, they will be only a scientific article somewhere in the cloud.”

The emphasis on access to knowledge is strongly echoed by Silviu Brill, Director of the Pain Institute at the Tel Aviv Medical Center, and Honorary Secretary and Chair of the Cancer Task Force at the European Pain Federation (EFIC). “We need patient education, we need to lead them through social media, through the cancer institutes, through all avenues, so that they recognise the right of patients to be treated. We need education also for young doctors and trainees, teaching about cancer pain, pain assessment and pain treatment. I think those can really make a difference for adequate pain treatment.”

As he points out, the addiction crisis that blew up in the US has made that task harder. “The reluctance and fear we see towards opioids, both from patients and doctors, are a result of the opioid crisis that crossed the ocean, from America to Europe. But for severe pain, opioids are still the gold standard of treatment.” Across the continent, countries and healthcare systems face different challenges, he argues, which may also differ between hospitals.

“There is not just one thing to address. We should go in every country, or every big cancer centre, to visualise the barriers. Because they can be very, very different: not enough doctors, not enough nurses, doctors without knowledge about adequate pain treatment, and cultural differences – where one doctor might be very open towards treating patients with opioids, another one, in a nearby hospital, might never give opioids, ever.”

A position paper on the Societal Impact of Pain Platform – an initiative by EFIC and Pain Alliance Europe, the European umbrella organisation for people with chronic pain – argued that pain needs to be included among the indicators for assessing the quality of a healthcare systems across Europe. Brill points out that pain does not just cause discomfort, it can also impact severely on people’s social life and ability to function. “Assessing also the social impact of pain, not treating only the pain, but looking multifactorial at the quality of life and activity of patients, will be a strong thing that can improve the quality of our treatment,” he says.

Similar to the approach Bošnjak is championing at the IORS, EFIC is proposing a multi-professional approach towards treating cancer pain. “Treating only pain is an old-fashioned way of looking at the issue. We need to treat the patient as a whole, this needs other professions, such as psychologists, physiotherapists, and also rehabilitation – all the resources available.”

“We would need to set high standards that can be easily measured: Are patients asked, every time they see a doctor, whether they experience pain? How long does it take for patients to be seen in a pain unit? And how long until their pain is reassessed? Are patients asked about side effects of pain treatment? These are examples of quality indicators that can be easily implemented and can make a difference. Once we have quality control and set a high standard, the issue will be improved dramatically.”

Cannabinoids – the new(er) kids on the block

While patients are sometimes afraid or reluctant to take morphine, attitudes towards cannabinoids tend to be vastly different. “Somehow, patients are more open towards using cannabinoids than morphine or other guideline-based opioids,” Bošnjak observes. “Of course, we are very open to explore every possibility to find new medications to treat pain. But patients are maybe too optimistic about or not careful enough with cannabinoids, and the actual data about their efficacy in cancer pain management.”

In early stages of cancer, cannabinoids might be seen as an option, says Dzierżanowski. “They may appear an alternative for moderate pain and accompanying symptoms such as chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, spasticity, seizures, mood disorders or loss of appetite.” However, the evidence is still too weak to recommend their use as a first-line treatment for chronic pain, he says. “Approaching cannabinoids, we should avoid the reluctance that was typical towards opiates in the past decades, which appeared not rational. But we still do not have standardised cannabinoids, and oral formulations like pills or solutions, that would be easier to administer. And further randomised clinical trials are necessary to confirm or redefine the role of cannabinoids for the treatment of cancer pain and in palliative care settings.”