Inequalities in social, economic and educational status are inherent in all societies, to a greater or lesser extent. The discovery that a person’s health and life expectancy are closely tied to their position in the social hierarchy opened up new opportunities to improve public health by addressing the inequalities, and specifically the factors that link social inequality with health – the so-called ‘social determinants of health’, which include, for instance, education, job opportunities, healthy housing and access to a nutritious diet and to opportunities for an active lifestyle.

Much of the pioneering work in this area was done by the epidemiologist Michael Marmot, whose influential ‘Whitehall Studies’, which focused on British civil servants, demonstrated the steep inverse association between social class and mortality from a wide range of diseases, and began to uncover some of the mechanisms at work.

Marmot has since been highly influential in informing policies aimed at promoting healthier communities and reducing health inequalities, both at UK and international level. More recently, the Marmot-led Institute of Health Equity has provided expert analysis and advice to individual cities and regions that want to prioritise reducing health inequalities within all aspects of their policies, including economic development, education, leisure, housing, and more. The cities that have signed up to this approach are known as ‘Marmot cities’. Many of them are in regions with severe deprivation in a high proportion of neighbourhoods. All of them see their ‘Marmot city’ designation as source of civic pride.

The question of what impact prioritising health equity in local and regional policy making can do for cancer remains to be seen. There are good reasons for optimism. That lower socio-economic status is linked to a higher risk of dying from cancer has been known for a long time, with the disadvantage kicking in from the point of prevention to early detection to accessing the best treatment, care and follow-up. The extent of that disadvantage was recently made clear in a 2023 study published in Lancet Oncology, which showed that, in the UK, men under the age of 80 are almost 80% more likely to die from cancer if they live in some of the most deprived districts compared with the least deprived, with women being at 74% higher risk.

Looked at another way, this means that improving the social determinants of health for people living in more deprived neighbourhoods could greatly improve their chances of avoiding or surviving cancer. That is one of the outcomes the Marmot Cities hope to see.

The Whitehall studies

In the 1970s and 1980s, Marmot conducted the influential Whitehall Studies, which explored the connection between social status and health using all ranks of the British Civil Service (based in Whitehall, London) as the study population. The research unveiled a distinct gradient in health outcomes based on employment grade, with higher-ranking officials exhibiting better health and lower mortality rates compared to their lower-ranking counterparts. This investigation led Marmot to introduce the concept of the ‘status syndrome’. The landmark studies showed that an individual’s health and life expectancy are not solely related to access to healthcare or individual behaviours, and that health inequalities exist across all levels of society below the top 1 percentile, not just between the richest and the poorest. The awareness of this gradient is fundamental to inform policies that benefit the whole society.

Social policy, health and medicine

While Marmot provided the first robust epidemiological evidence of the strong association between social status and health, he was not the first to highlight the issue. In the mid-19th century, Rudolph Virchow – best known among medics as the ‘father of modern pathology’ – highlighted poor social conditions as a key factor behind a major typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia (1847–48), and he advocated for the key role of social policy in improving public health. Virchow famously characterised medicine as a “social science”, and said, “politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale”.

One hundred years later, social medicine came under a global spotlight when the World Health Organization (WHO) – newly established in response to post-World War II public health and humanitarian challenges – adopted a constitution that formally characterised health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being.” While Cold War obstacles initially hindered the acceptance of the concept of social determinants of health, the 1978 International Conference on Primary Health Care marked a turning point. The Declaration of Alma-Ata, issued at that conferences, recognised that: “the attainment of the highest possible level of health is a most important world-wide social goal whose realization requires the action of many other social and economic sectors in addition to the health sector.” Successful community initiatives, particularly in developing nations, have since propelled social determinants of health into mainstream discussions.

These efforts were boosted with the launch of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health in 2005. Chaired by Marmot, its remit was to review evidence, stimulate societal debate, and recommend policies aimed at improving the health of the world’s most vulnerable populations. The report, titled Closing the Gap in a Generation, focused on three very broad social policy recommendations: improve daily living conditions of deprived communities; address the inequitable distribution of power and resources; and understand and measure the problem.

Guidance for policy makers: the ‘Marmot principles’

In 2008, the British government sought Sir Marmot’s expertise to translate those recommendations into practical applications for England, conceivably one of the most unequal societies in Europe. The result was the influential report Fair Society, Healthy Lives, commonly known as ‘The Marmot Review’. Published in 2010, it featured six policy objectives, or ‘Marmot Principles’:

1. Give every child the best start in life

2. Enable all children, young people, and adults to maximise their capabilities and have control over their lives

3. Create fair employment and good work for all

4. Ensure a healthy standard of living for all

5. Create and develop healthy and sustainable places and communities

6. Strengthen the role and impact of ill-health prevention

A second report, Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On,” added two further principles:

7. Tackle racism, discrimination, and their outcomes

8. Pursue environmental sustainability and health equity together

These eight principles were formulated by identifying what Marmot refers to as “the causes of the causes.” To identify and prevent the causes of illness is very important, he argues, but equally important is to identify and prevent the causes of the causes. In the case of modifiable cancer risks, for instance, while information campaigns on the benefits of a healthy diet, exercise, attending screening and so on are essential, many people lack the capacity to make the necessary changes in their lives due to a range of interconnected factors including income, education, employment, living conditions.

Marmot offered a graphic example of this in a presentation he made at the 2023 World Oncology Forum. For people in the poorest quintile of households, he explained, adhering to the healthy eating guidelines that are recommended to lower your risk of cancer and other chronic diseases would require spending 50% of your household income on food, which could make it impossible to also cover other essential needs, such as rent and heating. In contrast, those in the top quintile need only allocate 11% of their household income to maintain a healthy diet.

The challenge of addressing these ‘causes of causes’ goes beyond identifying the specific policy goals defined in the ‘Marmot principles’. The bigger question, perhaps, is how to ensure the measures to improve the social determinants of health benefit the more deprived and marginalised parts of the community that are most in need.

The ‘Marmot Review’ cautioned against using ‘means testing’ to restrict support to those who can show they fulfil specified needs-based criteria. Given that issues of low social status and lack of empowerment are part of the problem, it argued, the solution cannot involve providing support in a way that stigmatises and further exacerbates those social distinctions. That objection came on top of logistical arguments relating to the high administrative costs, misclassifications, under-coverage, and ‘leakages’ (recipients who do not meet the criteria for assistance).

Marmot argued instead for an approach based on ‘proportionate universalism’ – universal interventions that are weighted proportionate to individuals’ level of disadvantage. This approach recognises that while universal policies benefit everyone, additional targeted measures are necessary to address the specific needs of disadvantaged populations and reduce health inequalities.

Social determinants at a time of austerity

Published in 2010, the Marmot review came at what turned out to be a bit of a turning point for public health in the UK and much of the developed world – and not in a good way. The decade that followed saw severe cuts in funding public services, as governments sought to recoup the large sums they had spent on bailing out the banks following the financial crash in September 2008. Public sector expenditure in the UK fell from 42% of GDP in 2010 down to 35% by the end of the decade.

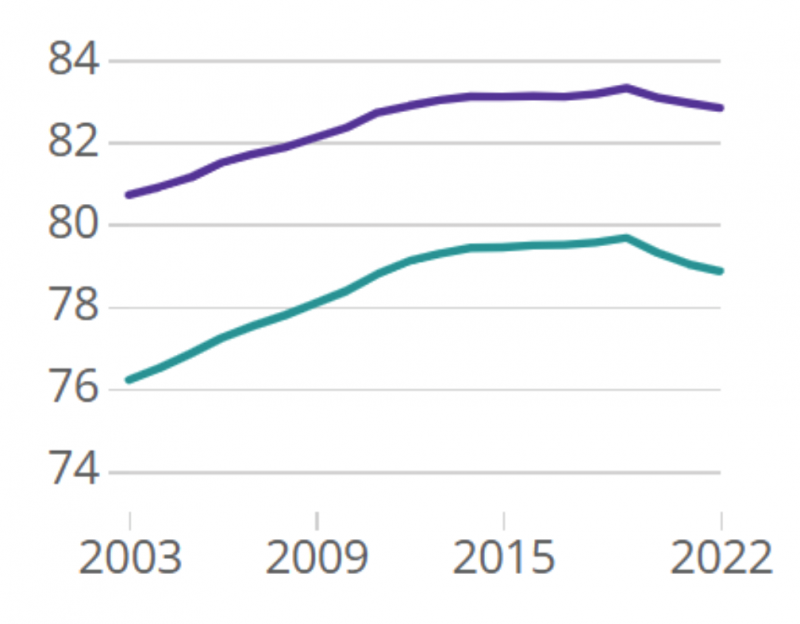

So, when Marmot came to write the 2020 Marmot Review, 10 years on, far from being able to report a reduction in the health inequalities relating to social deprivation, he pointed instead to evidence that it was getting worse. Between 2010 and 2018, the difference in life expectancy between the most and the least deprived deciles had increased from 9.1 to 9.5 years for men, and from 6.8 to 7.7 years for women. During that decade, the steady increase in average life expectancy, which had been a feature since the 1920s, had levelled off, but that ‘average’ concealed major differences by deprivation level. In every region, men and women in the least deprived 10 percent of neighbourhoods had seen increases in life expectancy, while in the most deprived 10 percent of neighbourhoods life expectancy for women actually declined in most regions, while male life expectancy in these neighbourhoods either decreased or remained pretty much level. For both men and women, the largest decreases were seen in in the most deprived 10 percent of neighbourhoods in the North East and the largest increases in the least deprived 10 percent of neighbourhoods in London.

Marmot argued that the deterioration in many of the social determinants of health over that period was a contributory factor that explained the widening inequalities and faltering growth in life expectancy: “While attributing causation is complex, it is likely that some of the key social determinants have affected health inequalities in recent years – although because many are experienced early in life, it may be too soon to see impacts yet.” In the period 2018 to 2020 the life expectancy curve has actually started to drop, with the biggest drops occurring in men living in the north east, which could lend further weight to that line of argument.

Life expectancy in England

Office for National Statistics (2021)Life expectancy for local areas in England, Northern Ireland and Wales: between 2001 to 2003 and 2020 to 2022

Studies commissioned as part of the 2010 Marmot review indicate that reducing spending on public services and welfare could constitute a ‘false economy’ due to the costs associated with the resultant increase in health inequalities, as well as the slowdown in economic activity resulting from reducing levels of demand. Figures suggested at the time were around £31–33 billion a year ($40–42 billion) lost in productivity, a further £20-32 billion per year ($25–40 billion) lost in tax revenue and higher welfare payments, and a further £5.5 billion per year ($7 billion) in additional costs to the health service. Those amounts would be considerably higher in today’s money.

The first Marmot city

It was against this background of cuts in public services that the concept of the Marmot City was born. A key step came in 2011, when University College London (UCL) established the Institute of Health Equity under the Marmot’s leadership. UCL had been Marmot’s academic base, where he was Professor of Epidemiology for the majority of his career, from the Whitehall II study onwards. With the Institute of Health Equity, Marmot and his team were able to move beyond generating evidence and recommendations to also get involved in shaping “the development and delivery of interventions in Marmot Places [see box] and in organisations that have impacts on health to ensure they have health equity at their heart and address the social determinants of health.”

A Marmot Place

A Marmot Place is defined as a place which recognises that health and health inequalities are mostly shaped by the social determinants of health (SDH): the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, and takes action to improve health and reduce health inequalities.

In 2013, Coventry – a city that inspired the Specials’ 1981 hit ‘Ghost Town’, after the collapse of its industrial base in the previous decade – became the first to sign up to be a Marmot City, in an effort to boost the health of residents living in the most deprived areas. In practical terms, this meant that the City Council committed itself to shape its policies – including economic, education, leisure, housing and more – around improving the social determinants of health for the most deprived using the principle of providing universal services weighted towards those most in need. It also meant having access to advice and expertise from the Institute of Health Equity, which helped the Council to assess local health inequalities, develop and implement targeted interventions, and strengthen partnerships across sectors to create sustainable change.

In the following years, more cities and regions signed up to become Marmot Places. Many are in the north of England, where average life expectancy is persistently poorer than in the south; these include Greater Manchester, Gateshead, Cheshire and Merseyside, Lancashire and Cumbria, and Leeds. But they also include areas in the more affluent south of the country, where higher average life expectancies conceal large and growing disparities between wealthy and deprived neighbourhoods that may be located within a few miles of one another. The south east region of Kent/Medway, which has the highest life-expectancy in the whole of the UK, is in the process of joining that list.

Andy Burnham, a former UK shadow Health Secretary, and now the Mayor of Greater Manchester, argues that efforts to improve standards of health, particularly among the most vulnerable, need to be led by local authorities. “As Secretary of State for Health, you can have a vision for health services. As Mayor of Greater Manchester, you can have a vision for people’s health. There is a world of difference between the two.”

In the aftermath of the Covid pandemic, the Institute of Health Equity collaborated with Greater Manchester on developing policy recommendations to address the widening inequalities, with the stated aim of not just ‘building back better’ – a widely adopted aspiration after the pandemic – but to ‘build back fairer’. The report focused on addressing disparities in children’s early years and in educational engagement and attainment, rising youth unemployment and deteriorating mental health among young people. On the basis of that report, the city adopted policies to reduce digital exclusion; improve mental health; optimise travel support; and increase pre-employment apprenticeships and work placements. The analyses and recommendations developed for that and other Marmot Places are all available on the of the Institute of Health Equity website.

What could Marmot cities do for cancer?

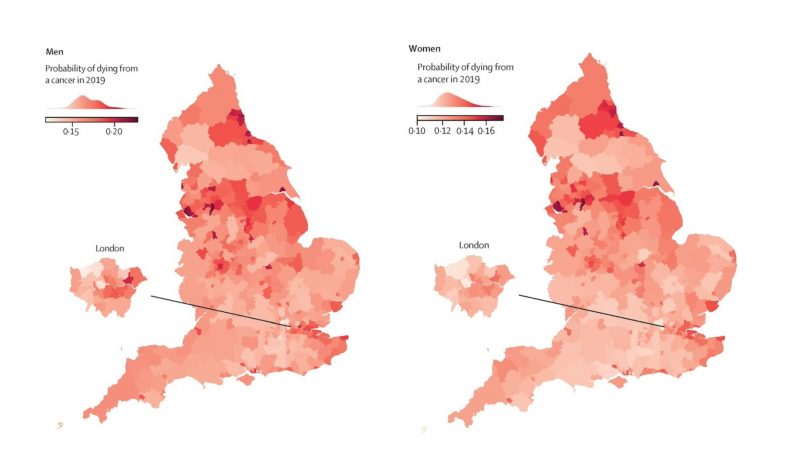

The close link between socio-economic deprivation and cancer has been understood for decades. It was starkly demonstrated in a 2023 report published in Lancet Oncology, which showed that men under the age of 80 are almost 80% more likely to die from cancer if they live in some of the most deprived districts compared with the least deprived, with risk levels in women being almost 75% higher.

They found that, “Although overall cancer mortality decreased in all districts of England [between 2002 and 2019], the reductions were unequal, with the largest declines almost five times that of the smallest. Some of the largest inequalities across districts in mortality, and the widest variation in change in mortality from 2002 to 2019, were observed for cancers strongly associated with behavioural and environmental risk factors, and those for which screening for precancerous lesions is available.”

The cancers showing the least geographical inequality in mortality across districts, they added, were those “with more heterogeneous and weaker associations with modifiable risk factors (i.e., lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and leukaemia)”.

T Rashid, JF Bennett, DC Muller et al. (2023) Mortality from leading cancers in districts of England from 2002 to 2019: a population-based spatiotemporal study. The Lancet Oncology. It is published here under a Creative Commons CC-BY. © 2023 The authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd

That finding highlights the key role that disparities in social determinants of health play in fuelling inequalities in cancer mortality. It also flags up huge opportunities to reduce cancer mortality by taking effective measures to improve those social determinants.

Interestingly, the authors echo the views of the Mayor of Greater Manchester, in advocating for those measures to be devised and implemented locally. “Our results on heterogeneous trends in mortality, particularly for cancers with modifiable risk factors and potential for screening for precancerous lesions, indicate that reducing these mortality inequalities will require factors affecting both incidence and survival to be addressed at the local level,” they say.

If that is the case, then the ‘Marmot City’ approach could have a lot to offer.

Marmot on the international stage

While the ‘Marmot City’ approach has so far only been piloted in the UK, the Institute of Health Equity at University College London, led by Michael Marmot, was and is involved in many international projects, including:

- The Commission on Equity and Health Inequalities in the Americas, set up in 2016 by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), which resulted in a report, Just societies: Health equity and dignified lives, that outlines drivers of health inequalities in the Americas and offers practical recommendations for addressing them.

- The Regional Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, established in 2019 to review health inequities in WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Region. The findings and recommendations were published in the report Build Back Fairer: Achieving Health Equity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region.

- A project with the Chinese University of Hong Kong involving a series a studies, the first of which has been published under the title Build Back Fairer: Reducing Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health in Hong Kong.

The Institute of Health Equity is also involved in the current WHO Special Initiative for Action on Social Determinants of Health for Advancing Health Equity, which aims to address the root causes of health inequalities by developing reliable strategies, models, and practices that can be adopted by WHO offices, UN staff, and country leaders. The Multi-Country stream of this initiative targets improving the social determinants of health for at least 20 million disadvantaged individuals in 12 countries by 2028. During 2024, COVID-19 recovery policies in health, social, and economic fields in six countries will be informed by impact assessments that include social determinants of health equity.