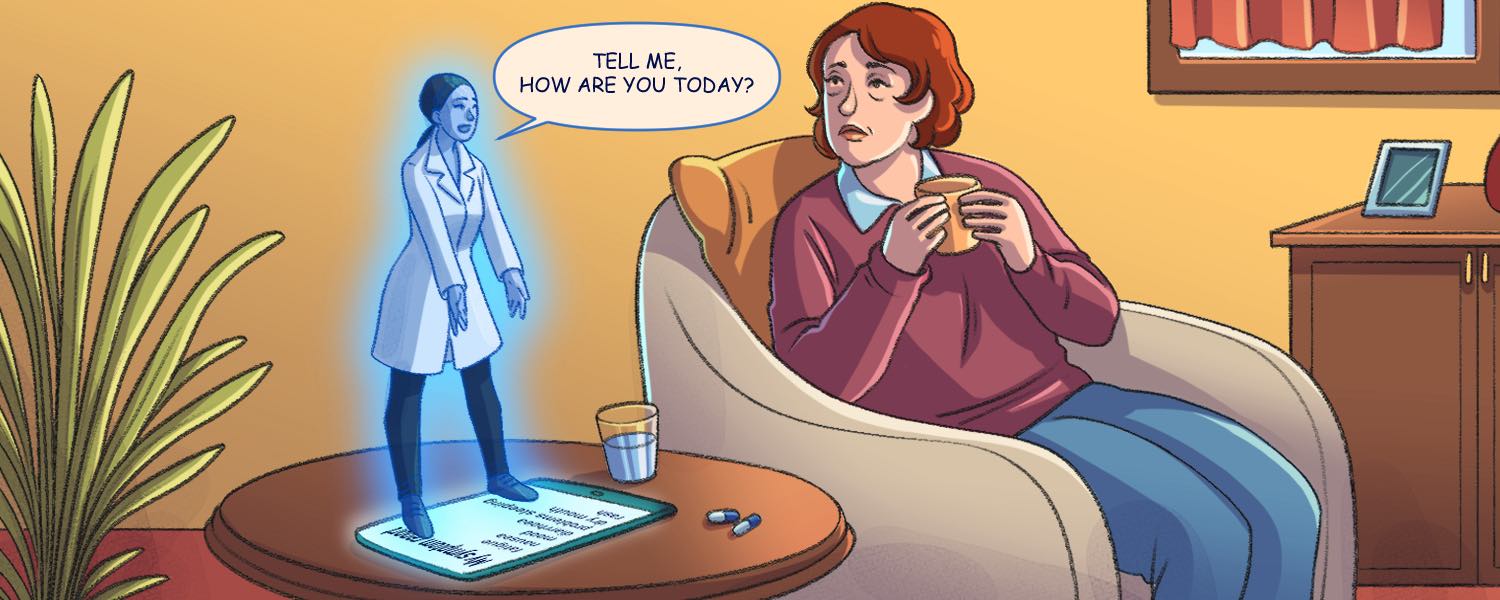

An older woman receiving treatment for breast cancer sits at home wondering whether to call her physician and go into the hospital. She’s on a new dose of a drug which she hasn’t had before and is struggling with nausea. Not unusual for a person with cancer on treatment, but it’s been days now and she’s getting increasingly fed up and struggling to eat enough. She gets a notification on her phone to fill in her daily symptom reporting survey and does so, truthfully reporting her symptoms.

At her oncology department in the nearest major city, some 200 kilometres away, a clinician gets a ‘ping’ about a patient to review, logs onto her computer and sees that the patient has been experiencing nausea for several days. She picks up the phone, talks to the patient and prescribes an anti-nausea drug which the patient can pick up at her local pharmacy, saving her the three-hour drive to the hospital, while ensuring her symptoms are effectively treated.

This fictional situation highlights the potential of patient reported outcomes (PROs), which are essentially a real-time snapshot about a patient’s status. They can take into account both physical and emotional metrics, and the information can be collected on paper, or increasingly via digital means.

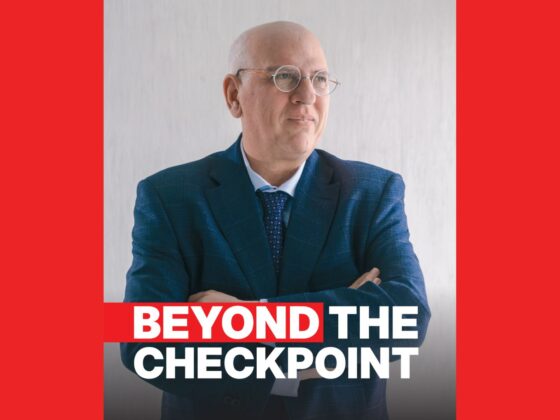

“In oncology, but also in many chronic illnesses, there are a lot of symptoms of disease and a lot of side effects of treatment,” says Ethan Basch, medical oncologist at the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and Chief of the Division of Oncology. “The way that people feel and function is essential to understanding if a drug works and if a treatment is effective. These quality-of-life measurements have been around for decades,” says Basch, who has played a leading role in promoting the PRO agenda for much of that time, including work with the US National Cancer Institute (NCI) on developing the PRO-CTCAE – the patient-reported outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (the traditional clinical tool for reporting adverse events in clinical trials).

With PRO monitoring, the information is sourced directly from the patient, giving clinicians direct data about how their patient is faring at any given time. This comes with the added benefit of avoiding potential unintentional bias being introduced by subjective interpretation of spoken, or non-spoken cues that patients may intentionally, or unintentionally give when communicating traditionally to clinicians.

For treatment regimens as complex as most people with cancer face, PROs introduce the possibility of monitoring often subjective metrics such as pain, nausea, fatigue and mental health, adherence with medications, and even financial toxicities. In the setting of trials of new drugs, new dosing regimens or new treatment combinations, these sorts of symptoms understandably get less attention from often busy and over-worked care teams than do potentially life-threatening or treatment-limiting side effects. They can, however, dramatically affect quality of life and even treatment outcomes. PROs allow researchers, patients, and clinicians to pick them up.

“I know breast cancer patients who get very little information about what to expect from a drug from their oncologists. They find what they need from other patients in online groups,” says Diana Chingos, a cancer survivor and patient advocate in research based in Los Angeles, who has participated in many projects on PROs. “Incorporating PROs into cancer research studies offers everyone a more comprehensive assessment of a drug, especially how it affects patients in their daily lives. Knowing what to expect is an extraordinary benefit.”

As she points out, given the marginal survival benefit offered by many cancer drugs, to make informed decisions, patients need good information about the potential impact the drug could have on their daily lives – and that information needs to be gathered routinely within trials. “Until survival endpoints can be greatly improved, the focus needs to be on quality of life,” she says. “I’ve witnessed the approval of drugs that demonstrate impressive scientific accomplishment but diminish quality of life so substantially that you have no life. That is not success in drug development, and this is not how people want their lives to end,” says Chingos, noting that many people who enrol in early phase clinical trials for new drugs have terminal cancer.

“Providing insights on a PRO survey is the least burdensome way for patients to contribute to a clinical trial, assuming reasonable survey frequency,” she adds. “Providing an opinion isn’t physically invasive and doesn’t require a potentially uncomfortable encounter in a healthcare setting. Cost isn’t an issue for the person taking the PRO survey. And it could potentially benefit the patient if knowledge is gained by the study physicians.”

PROs in routine care: the evidence

The use of PROs is now expanding to include more frequent patient assessment to improve the quality of patient care, says Basch. “Over the past 15–20 years, there has been growing interest in using patient reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine care, daily care, asking how we can use PROs to improve the care that we deliver and improve communication with our patients. That comes out of a recognition that probably more than half of the symptoms that patients experience during cancer treatment go undetected by us as clinicians,” he notes.

More than half of the symptoms that patients experience during cancer treatment go undetected by us as clinicians

A randomised controlled study of 1,191 patients with metastatic cancer across 52 oncology practices in the US, published in early 2024, showed that those who completed weekly surveys about their symptoms reported better symptom control, physical function, and quality of life.

There is some evidence that PROs contribute to improved survival, too. A meta-analysis published in 2022, which collated six studies, suggested that patients who had PRO monitoring had better overall survival than patients treated with the standard of care. The benefit was greatest in patients with advanced lung cancer.

Those findings are in line with evidence from an earlier study by Basch and colleagues, published in 2017, which found that patients with metastatic cancer who provided self-reports of 12 common symptoms had a median overall survival of 31.2 months – more than five months longer than patients who received only the standard of care, who survived 26 months on average. In the Canadian province of Ontario, a large retrospective study, published in 2022, looked at adults with cancer diagnosed between 2007 and 2015. The researchers paired data from each patient who had reported PROs with a patient who had not, but who had similar characteristics, generating 128,893 pairs. The study found that survival was higher in those who had participated in PRO monitoring at 1, 3, and 5 years after diagnosis, although the differences between the groups declined with time.

PROs in routine care: how it works

“We’ve used patient reported outcomes on things like quality of life as endpoints for a very long time,” says Gabrielle Rocque, medical oncologist and Associate Professor of Medicine in the Divisions of Hematology & Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “What’s different in my mind is the shift towards using patient reported outcomes as interventions, as screening tools and part of the care delivery system, not just at the end for evaluation.”

Her programme involves patients on active cancer treatment receiving a weekly questionnaire via text or email about their symptoms. If the questionnaire highlights anything moderate or severely concerning, the patient receives a call from a nurse to discuss their symptoms further.

“We are the main NCI designated cancer centre in Alabama and some of our patients travel four or more hours to get to us. We’ve had patients who have reported their symptoms remotely and we’ve then been able to help them manage them at home. The key is bridging communication gaps to improve patient care,” she says.

Previously, paper questionnaires were often used to collect this data, but with great advances in digital health, many PROs are now collected using phone apps, tablets, or online portals, which patients can access as inpatients or outpatients. This data can automatically be added to electronic health records, with trends and changes over time instantly accessible to the patient’s care team. Making it routine can also reduce barriers to patients reporting things that may be bothering them, she says.

“Using PROs in this way normalises the experience of reporting problems that has the potential to be really meaningful for patients. Patients don’t have to ask themselves whether it’s worth bothering their physician with a phone call, it becomes routine. I think it takes away some of the power dynamics that can be really problematic in medicine.”

“Patients don’t have to ask themselves whether it’s worth bothering their physician with a phone call, it becomes routine”

As with many areas of virtual care, remote symptom monitoring has been highlighted to have the potential to reduce cancer disparities, by reducing certain barriers to access – including unhelpful power dynamics. However, the requirement of being digitally literate and having a phone or computer, and an internet connection, can be significant barriers in themselves.

“We are definitely seeing that technology and digital literacy and digital health literacy is a huge barrier to these interventions. Many people are still not that comfortable with technology. Everything we do must be done with purpose and with the needs of every patient and not just the patients for whom it is easy to reach,” says Roque.

At her institution a clinical navigator helps patients through the process of signing up to use the PRO system, shows them how to navigate the questionnaire, and goes through an initial survey with them. But a more general awareness about digital literacy in the community is also prudent, as Roque has found out through an American Cancer Society funded project on digital health literacy.

“We’ve actually had to take a few steps back, because we realised our community needs really basic education,” she admits. “For example, I can’t put up a QR code and expect them to go get that information. We need more digital literacy training in the community, to reach the public, particularly older adults, who may not have the same levels of skills, and help to train them.”

Chingos adds that PRO tools can themselves have limitations. Asking patients to record, on a Likert (numerical) scale, the severity of a symptom over “the previous 7 days”, for instance, may capture extremes, but not the whole story. Reducing complex pictures to a simple number “may optimise its use for research” – or indeed analysing trends in a single patient’s symptoms history – “but [it] may not optimally capture the patient’s experience.”

“There should be a way to write in a personal report where appropriate, and for that to be included in the analysis,” she says.

PROs in routine care: the future

Despite these challenges, the arguments in favour of integrating routine collection of patient reported symptoms into patient care are widely accepted, Roque believes. “I think if you ask the majority of physicians, people can recognise the potential benefit of patient centred outcomes. I don’t think there’s a lot of oncologists that would say, ‘Oh, this is totally useless.’ But what I think is tricky is: how do you operationalise that? And how do you bring that into practice and into workflow?”

“I think we do need to be really thoughtful about workflow, design and resourcing”

She acknowledges concerns among some clinicians about whether collecting PRO data will create increased workload for them and their staff, and what value will be added by this extra work. “I think there’s more hesitation about those aspects than there is about using patient reported outcomes as a concept. Some of those concerns are very legitimate and very fair. And I think we do need to be really thoughtful about workflow, design and resourcing,” she says.

But change is definitely on the horizon. The FDA (US regulators) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (which provide government healthcare insurance) are observing the ongoing work led by Roque and Basch closely, and the FDA recently issued guidance on using PROs in cancer clinical trials.

Roque has no doubts that integrated PROs are the future both in research and in clinical care. “Once we get the basic systems into practice, I think we’re going to end up in such an amazing place to be able to think about how we customise systems to get different [PRO] questions to different patients based on their disease, and their previous treatment responses and toxicities.”

Illustration by Alessandra Superina