Miriam Espinoza, a food vendor from Michoacán, Mexico, still remembers the day she received her cancer diagnosis in 2019. After months of waiting for a CT scan and several visits to gynaecologists, who told her that the lump in her breast was fibrosis, she was finally sent for an emergency oncological consultation. The doctor told her she had stage 3 breast cancer – she was 39 years old. That day, a battle began to secure treatment within a healthcare system that is struggling to deliver in the face of fundamental restructuring.

Since 2019, thousands of cancer patients in Mexico have been affected by shortages of medicines and treatments in the public health care system, that have been widely attributed to failures in the planning and implementation of major changes to the purchasing, distribution and treatment systems that were introduced by the Government of Andrés Manual López Obrador (see for instance Lancet 2021 398:289–290; Health Syst Reform 2022, 8 (1), e2084221).

Reform to the healthcare system was one of the flagship policies that brought López Obrador – known as AMLO – to power in the 2018 general election. The promise was to tackle corruption and widen access to healthcare. A major policy plank involves moving towards a universal healthcare system in which citizens not covered by social security can access all health services, to be delivered – not just paid for – by public providers. Centralising control over purchasing, including medicines, is another key plank aimed at reducing corruption and maximising value for money.

However, the new system passed around the responsibility for purchasing medicines for public health institutions between organisations without clear guidance on how to do it. It went from the Mexican Institute for Social Security—until then in charge of consolidating the purchases of medicines— to the Treasury, then to the newly created Health for Wellness Institute (INSABI), then to the United Nations Office for Project Services (which helps UN countries implement national initiatives in culture and health), and finally it landed on the desk of Birmex, a state company in charge of producing, importing and developing vaccines. This year the government has announced that the responsibility will revert to INSABI and the Ministry of Health, after the problems with purchasing medicines also extended to the process of distributing them.

As part of these reforms, INSABI – which had been created to guarantee free access to healthcare for everyone – replaced the Seguro Popular health insurance system introduced by previous governments, which had widened access to many healthcare services, but fell far short of universal health coverage.

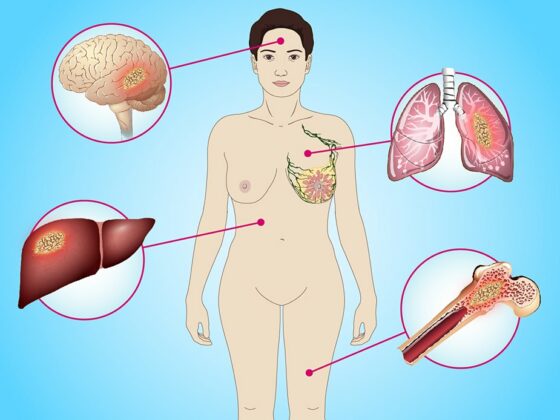

Critics of Seguro Popular argued that 20 million Mexicans – around one in five of the population – were not covered by that or any other insurance, and that even with the insurance, out-of-pocket expenses remained unaffordable for many (Health Syst Reform 2020, 6(1): e1763114). The number of conditions for which treatment costs could be claimed under Seguro Popular was also limited; while a few cancers including breast, cervical and all childhood cancers were covered, the insurance would not pay out for treatments for melanoma or cancers of the lung, liver, pancreas, stomach, head and neck cancers, certain leukaemias and more. Many healthcare providers were also reluctant to provide treatment even for conditions covered by Seguro Popular, because of the often lengthy delays in getting reimbursed by the system.

Despite its limitations, however, Seguro Popular did help people like Espinoza access the treatments they needed for their breast cancer diagnosis. That access is now far less reliable as a consequence of the lack of clear guidelines for INSABI’s operation and the failure to get the new drug purchasing and delivery systems up running effectively– not to mention trying to do all that in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Like many other cancer patients in Mexico, Espinoza cannot afford the chemotherapy, laboratory tests, scans, and other procedures to treat her disease. She has three children to support with her monthly income of US$200. One chemotherapy dose costs at least $250.

“It’s a devastating disease, and then it also affects you financially,” she says, remembering the first time she was told that the clinic didn’t have cyclophosphamide and she couldn’t have her complete treatment. “That takes an emotional toll on you.”

She and other patients began organising social media groups to help each other. They would share information about people who had a spare dose of medications, or about when doses might become available at clinics. They began complaining and demanding their rights to treatment – something that the medical authorities from their clinics and hospitals didn’t like.

They would share information about people who had a spare dose of medications, or about when doses might become available at clinics

“A hospital deputy director told us to disband this group because they were going to take away our medical insurance if we didn’t,” Espinoza remembers.

According to the Mexican patient advocacy group Nosotrxs, the number of dispensed drugs decreased by 24 million between 2019 and 2020. During the first quarter of 2022 the level of dispensing was at its lowest for six years. Cancer was the most impacted disease and the Covid-19 pandemic made matters worse. Oncological appointments for women fell by 57% between 2019 and 2020. In the same period, medical referrals for children with suspected cancer fell by 52%.

Tensions in the country built. In 2019, a group of parents of children with cancer blocked the national airport in Mexico City, protesting that their children were dying because of lack of medicine. Protests continued in the years that followed. In August of 2022, a group of parents and patients marched through the streets in Mexico City.

The issue has become a wider political flashpoint, with one Government minister saying that “We see this idea of children with cancer who do not have medicines increasingly positions as part of a campaign … of international right-wing groups seeking to create this wave of sympathy in Mexicans with an almost coup-like vision.”

While this may be true, the disruption in access to treatments among those well served by the previous system, and the stress and suffering, and potentially fatal consequences, for many patients is real.

In 2022, a group of protestors went to the Palacio National in Mexico City, the seat of the federal government, to bring their grievances to the health secretary Jorge Alcocer, but were angered when he refused to meet with them. Fewer than ten people were allowed in to talk to him. Espinoza was one of them.

“He said that all the oncological drugs had been one hundred percent supplied,” she recalls. When she heard this, she interrupted. “I told him that this was a big lie because there were none in Michoacán.” Her lawyer, Andrea Rocha, was also there.

Rocha had lost her grandfather when she was little, because her family couldn’t afford the medicine. When the cancer drugs shortage began in 2019, she stepped in. She met the parents at the first protest in the airport and offered to help them file an amparo, a legal tool that seeks the protection of human rights established in the constitution. The parents were sceptical, and they were scared they would lose their health insurance as retaliation. Still, a few went through with it, and they saw some results.

“The few medicines that do arrive [to the clinics] are, unfortunately, given to the parents who seek the amparo,” Rocha said.

“I never imagined that this would go on for so long and I still can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel”

Since 2019, she has provided free legal help to more than 240 patients from all over the country. “When I filed the first amparo, I never imagined that this would go on for so long. I never imagined such indolence on the part of the authorities,” Rocha said. “It’s a long night for me, and I still can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

The pandemic worsened the situation by further disrupting manufacturing and distribution systems for medicines. The government had to redirect the budget destined for healthcare services, 6.5% of its GDP, to treat COVID19 patients.

The medical community is struggling too. Bianca (not her real name), a doctor at the National Cancer Institute in Mexico City, has seen medical supplies get lower and lower. She recalls the case of a young breast cancer patient who started her chemotherapy course among a group of 15 women. “Because there was no chemotherapy, of that group of 15 there were seven left at the end. The others didn’t come back or died.”

Talking with her oncology colleagues, she keeps hearing about all the patients they are losing because they are unable to treat them. It upsets her every time. But she, like her colleagues, is fearful of speaking out, being identified and facing the consequences at work.

Other oncologists, however, particularly those whose patients were never covered by the Seguro Popular system, remain optimistic about what the new system could offer.

Haematologist Tomás Guzman (not his real name), who spoke to Cancerworld in 2021 about the implications the health system reforms would have for his patients, said “Before there was imatinib in the pharmacy but the patients had to buy it, the medicine was there and there were many patients who, even if it was the cheapest price, could not buy it. Now what I am seeing, and this is something I like, is that if a diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukaemia is made and the drug is in stock, I can immediately indicate it and the patients will no longer be worried because they cannot afford to buy it at the moment, but they go to the pharmacy and there they receive it.

“The problem is when it runs out or in the hospitals it still does not arrive, and this is the problem because if it is not possible to buy it cheaper or if it is not available in the pharmacy, then the patient has to find a way to get it and buying it outside in a pharmacy at public prices is impossible for most patients.”

Guzman wants to see the new system develop and function properly. “I believe that the diseases included in Seguro Popular, those diseases did benefit quite a lot, but it definitely did not include all of them… If they said to me ‘well, what do you want, a health system where only certain diseases are covered or a health system where all diseases are covered and patients can have free access to the drugs they need? Well, I would opt for the second paradigm. But, obviously, that it works well, that it is not half-baked, because otherwise, neither one nor the other is solved.”

According to Octavio Gómez-Dantés, lead author of a 2022 paper on the lessons from recent changes in pharmaceutical procurement in Mexico, “the problem is that now there’s not even clarity about who should be held accountable for deaths related to the shortages. “The procedures for medicines and everything else are not being carried out as required by law,” he says.

Before the changes, there was a system in place to track public sector medicine purchases called CompraNet. “Until 2018 we were able to follow in a timely manner how many drugs they were buying, how much they had cost us, to whom they had been distributed, how many belong to public health care institutions,” said Gómez-Dantés.

Now, the information has become scarce. The CompraNet website crashed in July 2022, and the Government wants to eliminate the system altogether. “We have a problem of bad procurement, we have a transparency problem, and we have an accountability problem.”

We went from a situation where there was corruption, but there were medicines, to one where there are no medicines and we don’t know if there is corruption”

There are some lessons to be learned from the past four years, Gómez-Dantés believes. The first is that something as complex as the purchase and distribution of medicines needs to have a solid system in place based around expert clinicians, pharmacologists, health economists and managers who know the drug market very well. The second is that any modification to the purchasing and distribution system must not jeopardise the supply of medicines.

“We went from a situation where there was corruption, but there were medicines, to a situation where there are no medicines and we don’t know if there is corruption,” Gómez-Dantés says.

“What had to be done was to fight corruption, not to take apart a system that had generated good results,” he says.

Guzman disagrees. “I believe that all these bureaucratic issues that may be holding up access to drugs are the ones that should be solved,” he says, and said that in the case of imatinib for treating chronic myeloid leukaemia, supply issues started improving back in 2021 – though not fast enough. “Now there are already patients with recent diagnosis, at least in some hospitals, who are already being able to receive free treatment… Medicine is starting to arrive from the hospitals themselves… But, it is not homogeneous in all the hospitals of the Ministry of Health.”

Like Gómez-Dantés, he said he would like to see greater transparency about what is happening and why. “I talk to many colleagues and there are some where it still does not arrive. And I do not know why it is so heterogeneous. Ideally, access to these drugs would be guaranteed in all hospitals.”

In August 2022, AMLO promised that the country’s new healthcare plan would be optimally functioning as of the first trimester of 2023. “We are reversing all that was delayed [with the pandemic],” he said.

Meanwhile, Espinoza and other patients are still locked in a day-to-day battle for survival. Whenever a patient contacts her because they can’t get their medications, she offers her help. “The treatment is one more day of life. It’s the hope to have one more good day to live with your family.”