For decades, cancer treatment has been anchored firmly within hospital walls, where the complexity and risks of chemotherapy seemed inseparable from clinical infrastructure. But as newer, less toxic therapies emerge, a quiet revolution is taking shape: the idea that certain cancer treatments may be safely delivered in the comfort of a patient’s home.

The motivation is clear: reduced hospital congestion, lower costs, fewer long commutes, and relief from the emotional and physical toll of repeated clinic visits. Yet this shift raises essential questions about patient selection, sterility, training, emergency preparedness, and logistics, issues that will ultimately determine whether home-based cancer care becomes a sustainable and equitable model.

Some of the treatments currently being explored for home use include oral therapies, subcutaneous and intramuscular injections, and select intravenous (IV) infusions that carry a low risk of extravasation, a complication in which medication leaks outside the vein.

In 2023, during a clinical study in Nairobi, Nimi Alibhai became the first Kenyan to receive cancer treatment at home, a milestone that brought global innovation directly into a Kenyan living room. “A single nurse would visit my mum’s room,” she recalls. “She’d begin with triage, my weight, temperature, and blood pressure, and each treatment session took about an hour.”

Nimi was receiving a subcutaneous combination therapy called Phesgo, used to treat HER2-positive breast cancer, which can be administered in minutes rather than the hours required for traditional IV infusions. “Before I started receiving the injections every three weeks at home, I had completed eight cycles of chemotherapy, followed by surgery and radiation,” she says.

At first, she was apprehensive. “I was nervous, but the nurse followed strict hygiene and sterility protocols during preparation, administration, and clean-up. Soon, home felt like the right place to heal, especially for anyone with mobility challenges or who values privacy.” The nurse remained in constant communication with her doctor. “Nothing started until the doctor gave the go-ahead,” she explains.

The benefits were profound. “The risk of catching infections from other patients was lower. My chemo port was flushed at home. And there was no travelling or waiting. I felt less like a patient. I could have a snack, rest on my sofa, laugh with my family, and it eased so much of the anxiety.”

Nimi’s experience reflects a growing global movement to decentralize aspects of cancer treatment. While hospital-based care remains essential for many therapies, advances in targeted treatments and supportive care have opened the door to safer, more patient-centred models.

Expert Comments

Prof. Mansoor Saleh, founding chair of the Department of Hematology and Oncology at Aga Khan University Hospital, highlights the time factor. Traditional IV chemotherapy regimens can take hours. He gives the example of two commonly used HER2-targeted therapies, originally administered as lengthy IV infusions. “Pre-medication is followed by a slow infusion that may need to be reduced further if a patient reacts,” he notes. “Altogether, the process can take nearly six hours.”

Newer subcutaneous formulations can be administered in minutes and maintain steady therapeutic levels in the bloodstream. This shift, from long IV infusions to quick injections, is one of the innovations making home-based delivery possible.

The home-health programme involved in the study targeted patients requiring minimal nursing support, physician oversight, physiotherapy, or mental health care. The fact that a targeted biologic therapy could be safely administered at home illustrates how far oncology care has evolved.

Still, Prof. Mansoor cautions that even subcutaneous treatments carry a risk of allergic or hypersensitivity reactions. Because of this, they cannot simply be administered at home without trained medical supervision. In hospitals, staff have access to emergency equipment such as crash carts, tools not typically found in household settings.

Patient selection is therefore critical. Clinicians must evaluate medical stability, home environment, support systems, and proximity to emergency services before approving treatment outside the hospital.

Globally, oncologists see this as part of a broader reimagining of cancer care. Prof. Matteo Lambertini, a medical oncologist and associate professor at the San Martino Polyclinic Hospital and University of Genoa in Italy, notes that the increasing use of targeted therapies, not chemotherapy, now places the greatest burden on infusion clinics. “For many treatments, such as subcutaneous anti-HER2 therapy and several well-tolerated oral agents, we still have patients coming every two or three weeks or monthly to the hospital, even when there is no real need for all these consultations,” he says.

Research continues to highlight the feasibility and safety of home chemotherapy. In one study exploring patients’ experiences with home treatment, participants reported being better able to adapt to their circumstances, use their time and energy more efficiently, avoid long clinic waits, and realign their resources with what mattered most.

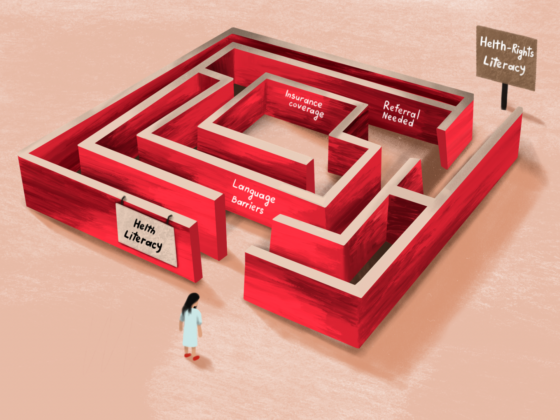

As promising as home-based therapy is, questions remain about equitable access. Not every household can accommodate medical equipment, and not every region has a strong home-health infrastructure, factors that may influence who benefits most from this model.

Yet the direction is clear. Together, emerging therapies and new delivery systems suggest that the future of oncology may be increasingly flexible, humane, and centred around the rhythms of daily life. For some patients, the journey through cancer may soon unfold not under fluorescent hospital lights, but in the quiet familiarity of home.

About the Author

Diana Mwango is an oncology journalist from Kenya, and a cancer survivor herself