In a remote, inaccessible and hilly area of the north-east Indian state of Assam, local residents of the Cachar district came together twenty years ago to form the Cachar Cancer Society for cancer prevention, detection and treatment. They felt a cancer centre was desperately needed in their region, as the nearest centre was in Assam’s premier city, Guwahati, which was 350 km away, and in those days took 20 hours to reach. At that time, most of the locals who developed cancer did not bother trying to get treatment, due to a combination of poverty, lack of knowledge, and lack of access. In an attempt to change that, Cachar Cancer Society established a treatment centre, as a charitable foundation, in the district capital Silchar.

Starting with a staff of only twenty-three, the Cachar Cancer Hospital and Research Centre (CCHRC) has expanded to employ more than 450 people today. It now has departments covering oncology, pathology, radiology, microbiology, epidemiology, tumour registry and palliative care, and other services and specialisations. It treats more than 5,000 patients every year, more than 4,000 of whom are day labourers employed in the rice fields and tea plantations or other agricultural work, with nearly 3,750 of them treated free or at subsidised rates. Perhaps the most remarkable statistic, for a population that cannot afford to live without their daily wage, is that more than 3,500 – 70% of patients – complete their course of treatment.

Much of the credit for this achievement goes to Ravi Kannan who, in 2007, left his post as head of surgery at a large and respected non-profit cancer in Chennai, one of India’s largest cities, to put his experience and expertise to the service of this under-served population. Credit should also go Chimoy Choudhury, the then director of Cachar Cancer Centre, whose determined efforts to convince Kannan to relocate to this small and remote facility finally paid off, and not least to Kannan’s wife Seeta, and his wider family, who supported the move – a brave act of commitment, given that “bombs and floods” was all they had ever heard about India’s North-East and Assam.

Their first trip to Silchar, in April 2007, was only meant to last a week. After countless phone calls and letters, the family had decided they should make the journey, to see the place for themselves. By the end of that week, Seeta Kannan was convinced that this was where “they were needed”, and they shifted base. That was 17 years ago. What Ravi Kannan, and his team, have achieved over that time is a source of hope and inspiration across India and well beyond.

Within two months of that visit, Kannan took over as the first oncologist director of the institute. While he knew a lot about operating on cancer and caring for patients, running a centre was a different ball-game. It took time for him to learn how to talk to different kinds of people, raise funds, and resolve conflicts. They solved problems as they encountered them, slowly, said Kannan. “We did not have a master plan, we did not have a corpus that would help us plan and implement everything in a time-bound fashion. We just grew organically.”

Step 1: Help patients to finish their treatment

One of the first problems Kannan noticed was that patients were dropping out of treatment. An internal study done in 2010 found that only 28% of the patients who came to them for treatment completed the course – an attrition rate of almost three in four. The data showed that 58% of the patients never came back to the hospital after diagnosis, and of the 42% who did return, most dropped out before the finishing line.

To address the problem, they provided treatment free of charge or at a nominal rate. Most of the treatment costs can be covered under state and national health insurance schemes for those below the poverty line, and the remaining costs were covered with the support of private donors and nonprofits like Indian Cancer Society and the US-based Care4Cure Foundation, which was set up specifically to support the Cachar Cancer Hospital.

To further ease the burden on patients they offered free meals and accommodation. But they soon realised that this was not enough, given that most patients were daily wage workers, whose families relied on their earnings of around $5–10 a day. Completing treatment for most patients meant taking six months out for chemotherapy, a further two months for radiation, and several more months recuperating from the treatment and getting back to strength. By that time, a year and half could have passed, which was not an option for them.

The hospital looked for additional ways to improve completion rates. It tried providing ad-hoc employment for the labourers, so they could continue to earn, it started calling patients the day before their scheduled appointments, to remind them to attend, and when patients dropped out, staff would visit them at home to try to persuade them to stick with the treatment. Around 2015, the hospital decided to waive the admission fees, which were already low. “Each time we adopted a measure, we thought it would be a game-changer and solve all our problems,” said Kannan, “but what it did was bring in a tiny bit of improvement.” They also adopted a policy that all patients who visit the hospital must be seen the same day – patients would have travelled long distances and spent a considerable sum of money to get there, so they shouldn’t be turned away for any reason and had to be accommodated.

The Cachar Cancer Hospital and Research Centre branded itself ‘pro-poor’. “When we treat poor people, we have to earn their trust 10 out of 10 times, and we cannot slip even once,” said Kannan. They understood that first impressions count, and that patients won’t come back again if their first visit gives them a feeling that their treatment will be very expensive. So they designed the hospital to be clean but modest, without fancy amenities or expensive architecture, and the staff were trained to be respectful and friendly to the patients.

At first, there were some in the staff who disagreed with some of these policies, said Kannan, but once they started visiting patients in their homes, they understood the situation, and they got onboard, “Now, everybody is on the same page and does everything they can do to help, like finding a job for the patient,” he said. Given their budget and spending priorities, the hospital does not employ receptionists and secretaries, said Kannan, and colleagues often multi-task and take on multiple roles to get the work done.

It is the combined impact of all these policies that has seen treatment completion rates rise from a little more then one in four patients to approaching three in four today.

Step 2: Embrace technology

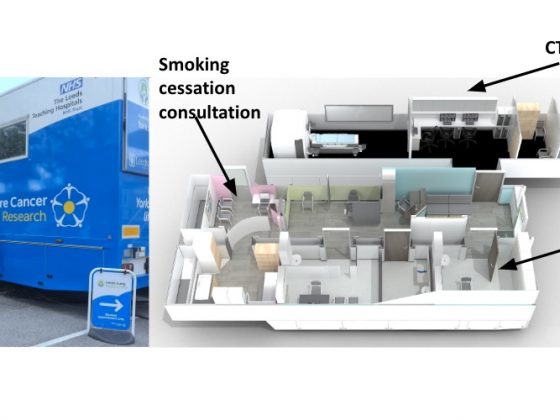

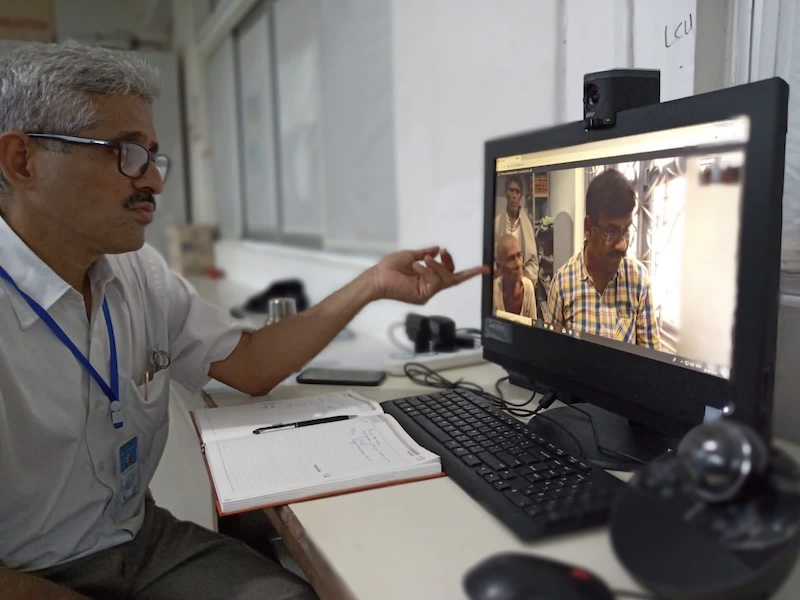

Despite his initial reservations, technology has proved to be a game-changer for the centre, said Kannan. Since 2014, the Cachar Cancer Hospital has set up five satellite clinics in hard-to-reach towns, where patients can receive chemotherapy and palliative care, and be monitored during follow-up, with remote support via video conferencing.

The hospital has also set up tele-ICU to give patients treated on its own premises access to specialist critical care expertise. High-definition cameras have been set up in the intensive care unit, allowing every patient to be monitored by a intensivist in Bangalore, 3,200 km away, through a healthcare company specialising in remote intensive care services. “We were among the earliest adopters of this technology in the world,” says Kannan. “Our newest experiment is in telepathology, with a group in Hyderabad.”

Virtual tumour boards are conducted via Zoom to get input from specialists across the country on individual patient cases. The hospital is also part of India’s National Cancer Grid – a network of 250 cancer care centres that support each other in many ways, including training and pooled procurement of cancer drugs.

Technology fixes have also been adopted to save time and money, said Kannan. To reduce patient waiting time, the hospital uses frozen section biopsies that take half the time for results compared with conventional biopsy. To save doctors’ time, CT scan-guided biopsies are taken by a technician rather than a doctor, as evidence shows that the outcomes and complications are similar for both. Pathology staff use kitchen extractor hoods in the laboratory as fume hoods, as a more affordable way, to protect themselves from formalin fumes.

All equipment and other facilities are upgraded through the support of Corporate Social Responsibility funds and through tie-ups with non-profits.

Step 3: Innovate in prevention and palliation

More than 50% of cancers in India’s North-East region are preventable, and can be attributed to chewing areca nuts, tobacco, alcohol and dietary practices. Educating the population about what causes cancer and how to reduce exposure to risk factors is a very high priority for Kannan – and one where technology is far less useful than human-to-human contact. The hospital recently adopted a Prevention Early detection and Palliative (PEP) programme, which builds on an existing long-running palliative care programme that involved staff visiting homes of patients who cannot make it to the hospital.

Under the new programme, staff also educate villagers during the visit about early signs of cancer, cancer prevention, and treatment options. This improves awareness and dispels myths about the disease, said Kannan, and can be done by staff without medical qualifications. “Both early detection and palliative are low-cost but high-impact activities that save lives and improve quality of life, and you do not need doctors or nurses to do it. Anyone can be trained to do these activities,” he said.

A global role model

The ideas that work in Silchar can work in many parts of the India and across the world, said Kannan, who identifies being open to collaborations as the key to success, “not only with those in the medical field but also economists, social scientists, IT professionals, to bring forth ideas to improve lives.” As the institute has grown and become better known, raising funds to support their work has become easier.

Kannan’s achievements have earned widespread recognition and many awards, including the Padma Shri, one of India’s highest civilian awards, in 2020, and most recently the 2023 Ramon Magsaysay award, which is known as ‘Asia’s Nobel Prize’. It is to his family, his colleagues, well-wishers and funders that he credits his laurels.

“Whenever I receive the awards, the whole community is happy because they have contributed to it,” said Kannan in his acceptance speech at the Magsaysay award ceremony, where he asked his two colleagues to take the stage with him. He welcomes the awards, in so far as they bring attention to the work and help it grow, but insists every success is about teamwork rather than individual achievements. “Friend-raising is far more important than fundraising; friends, colleagues, collaborators together can make a difference that one person can never make.”

A few years ago, colleagues at the Cachar Cancer Hospital and Research Centre brainstormed about the mission and core values of their organisation, which they would wish for all their colleagues to imbibe. They came up with compassion, an appropriate attitude, teamwork, developing an attitude of gratitude, scientific innovation, and delivering evidence-based care. Among these, Kannan considers compassion to be the most important.

Whether it is providing care to a small child with cancer, or a physician remembering that his patient loves singing Hindi songs, or one sick person providing care to another sick person, “Compassion has so many hues, so many varieties, but it is always about providing comfort,” he said. For Kannan, that is the most important yardstick for all the work he has done so far, and for what he hopes to achieve going forward.

The opening image shows Ravi Kannan sharing the joy of the Holi festival with one of his young patients.

All photos are courtesy of the Cachar Cancer Hospital and Research Centre (CCHRC). © CCHRC