The two largest cities in Türkiye have stepped in to promote HPV vaccination at a local level, including free inoculation for young people from the poorest families, as the state fails to deliver on its commitment to add HPV to the national vaccination programme.

On International HPV Awareness Day, March 4th, the Turkish government faced renewed calls to add HPV vaccination to the list of inoculations provided free to all citizens under the national vaccine calendar.

In 2022, the government announced its commitment to rolling out a national HPV vaccination programme, in line with the recommendations of the World Health Organization. So far, however, that pledge has remained unfulfilled.

In the absence of progress at a national level, Istanbul and Ankara – the two largest cities – launched their own initiatives to boost vaccination rates. The capital city of Ankara was the first to provide qualifying residents with free access to HPV vaccination, starting in March 2024. Istanbul followed two months later with its own free vaccination service.

Speaking to Cancerworld, a spokesperson for Health Affairs at the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality said the purpose behind the programme was “to increase awareness among citizens about the importance of HPV vaccination, and to ensure that all citizens throughout the county, including those who cannot afford the vaccine, have easy access to the vaccine.”

Istanbul residents aged between 9 and 26 who wish to benefit from the vaccine and who qualify for free access on the grounds of socio-economic deprivation are now able to request free HPV vaccination using an online form on the Municipality’s website.

Data on uptake rates have not been made available; however, the spokesperson reported that the scheme, which was promoted via social media, news outlets and other channels, has proved very popular, prompting the Municipality to extend the campaign throughout 2025.

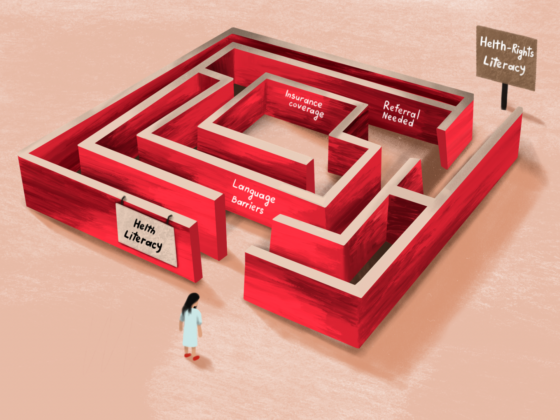

Istanbul and Ankara between them are home to a little under one-quarter of the country’s entire population. The great majority of Türkiye’s citizens, however, still do not have that access to free vaccination, nor to HPV awareness campaigns explaining the benefits.

Living with an incurable, threatening virus

A cervical screening study carried out by the Ministry of Health on a population of four million asymptomatic women, published in 2020, found a prevalence of infection with the HPV virus of almost 4.5%. HPV type 16, which accounts for 50%–60% of cervical cancers, was the most commonly detected. Though some of the infections picked up in that study will have been transitory, and resulted in no harm, there will have been many cases of chronic infection among them.

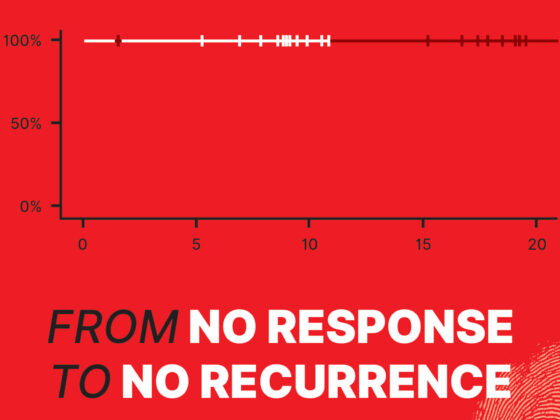

Fatoş, a cervical cancer survivor in her mid-40s who resides in the northeastern province of Rize on the Black Sea, lives with the realities of a chronic HPV infection every day. Her original cervical cancer was successfully treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy – though only after doctors had looked for, but failed to find, suspicious lesions during more than two years of frequent bouts of heavy continuous bleeding and weight loss.

However, medicine is not able to cure underlying cause of the problem – the chronic HPV infection and resulting inflammation. Since that initial operation, a further lesion developed which also had to be cauterised, and Fatoş remains at permanent risk of new cancers developing. “The only option is to extend the process through regular check-ups and careful monitoring,” she says. “Although my symptoms aren’t at an extremely high level right now, they are still present. For example, I still have irregular bleeding. I know that this is still ongoing.” One of those symptoms is persistent uterine infections. “These infections occur frequently, and when they start, they come with an intense odour.”

Since that initial operation, a further lesion developed which also had to be cauterised, and Fatoş remains at permanent risk of new cancers

Though HPV vaccination came in too late to protect Fatoş, she has paid out of her own pocket to get her older son vaccinated, and will do the same for her younger son, when he reaches 13 years of age. “I think the Ministry of Health should make this vaccine mandatory for everyone – for the sake of humanity and for the sake of our youth,” she says.

She doubts, however, that Rize province would initiate the sort of awareness campaigns and free vaccination policies that are now running in Istanbul and Ankara, partly because social stigma is a much bigger deterrent outside big cities. “The problem is that people won’t go to the municipality to ask for it, they would fear running into someone they know, and worry about what they might think. People are judgmental here,” she says.

Why the delay?

Including HPV vaccination within the national programme will be essential to extend protection to the whole country, argues Polat Dursun, Consultant Gynaecologist and President of the Turkish Gynaecological Oncology Association. Speaking to Cancerworld, he argues that there are a number of reasons that this is not currently happening, the most important of which is the cost. A single dose of the HPV vaccine costs about $100, which is very expensive compared to other vaccines, says Dursun.

Exacerbating factors, he adds, include pressures on the country’s health budget resulting from the global and national economic crises that followed the Covid-19 pandemic, together with Türkiye’s high levels of inflation, and the plummeting of the exchange rate, which is leading to huge price rises in imported medicines.

A survey conducted by Dursun and his team, of almost 1,500 women attending hospital appointments across four provinces in 2009, showed that, even back then, levels of awareness and acceptance of the vaccine were relatively high. Responses to their 22-item questionnaire showed that 45% of the women stated that they had heard about the HPV virus; 70% reported that they would accept HPV vaccines for themselves, 64% for their daughters and 59% for their sons.

While no national data are available for rates of HPV vaccination among the population targeted by the World Health Organization recommendations, rates are believed to be extremely low. Dursun argues that vaccine manufacturers should review their pricing policy, to make it more affordable.

He also points out that Türkiye has been ahead of the curve in implementing a national cervical cancer screening programme based on HPV tests rather than the much more widely used Pap smear tests. The HPV testing, carried out at Cancer Early Diagnosis Screening and Education (KETEM) centres, has increased uptake by around five-fold compared with the previous Pap-smear based screening programme, and is also more accurate, he says.

So, while the failure to follow through on promises to include the HPV vaccine in the national vaccination calendar is denying young people protection from a preventable cancer, Dursun stresses that good progress is being made in efforts to ensure that, where HPV is present in cervical cells, that is detected, and any resulting precancerous or cancerous lesions get picked up in time to be successfully treated.