The cost of cancer drugs in Turkey has escalated in recent months, putting some key drugs beyond the reach of most people. Legal routes to secure reimbursement are having some success, but that route is only available to some people, and it is adding delays, costs and stress, as Marwa Koçak reports.

An acute financial and economic crisis in Turkey has led to the value of the Turkish Lira plunging and domestic inflation soaring, reaching almost 70% in March.

The resulting price surge in imported cancer drugs is hitting cancer patients very hard, with many facing bills from US$1,000 to 4,000 a month to access drugs that are not covered by Turkish social security. These include immunotherapies such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, which are included in the WHO Essential Medicines complementary list.

Patients’ families are increasingly resorting to legal action to force social security to help cover their costs – with considerable success. As a result, access to cancer drugs is now being determined in part according to who has the capacity to bring these law suits, while pursuing these court cases is placing an added burden on families at a time when they need to focus their efforts on navigating the emotional and practical challenges that come with a cancer diagnosis.

How the law gets involved

Government social security support in Turkey is administered by the Social Security Institution, the social security SGK. Most healthcare services and medical test fees in Turkey are covered by the SGK, although a fee is also charged to individuals benefiting from statutory health services, with SGK covering 80% of the medication cost for employed people and their dependents. For people in retirement and their dependents, 90% of the costs are covered.

For cancer patients, the problem is that dozens of important cancer drugs are not on the list of reimbursed treatments. While this means large numbers of patients were never able to afford them, the recent massive price hikes put them out of reach of all but a tiny minority. This is why so many patients’ families are now taking court action to force the SGK to include the drugs on their reimbursement list, in line with what they believe is its legal responsibility.

The legal issue in contention here revolves around the criteria and methodology used for determining which drugs should be reimbursed, says Şeker Pınar Özcan, the President of the Istanbul Chamber of Pharmacists.

“While national and international treatment guidelines are taken as the basis in determining the items for the payment of drugs and treatments, economic parameters also have a significant impact on the reimbursement system in our country,” she says.

As a result, issues arise concerning the coverage of certain high-cost medications, leading to situations where patients, despite possessing the necessary documentation and prescriptions, face obstacles in getting the SGK to reimburse them.

MG Law in Kadikoy, Istanbul, is one of many law firms that are dealing with cases brought by patients and their families to force the SGK to reimburse them for cancer drugs that they have been prescribed, in line with national and international guidelines, but are not on the list for reimbursement. Lawyers Mete Gençer and Muhammet Deniz say they have supported many such lawsuits. Their legal efforts have succeeded in obliging the SGK to reimburse payments for more than 50 funded drugs currently excluded from the list, including: nivolumab, pembrolizumab, durvalumab, atezolizumab and other cancer drugs.

The trouble is that these cases are taken on a patient-by-patient basis, rather than a class action, and no standardised procedure or regulation has been implemented that would ensure the same access for all patients, explain the lawyers. As a consequence, they say, right now, only citizens who file lawsuits can obtain their rights.

The lawyers accept that the rising numbers of cancer patients securing reimbursement for treatments not currently on the SGK list is putting considerable financial pressure on the fund, which can translate into delaying reimbursement to patients.

The latest statistics show that SGK’s health spending in 2023 was TL 178.3 billion (US$ 5.5 billion) – nearly triple what it was in 2021. Medical costs account for the largest chunk of this expenditure, with cancer drugs accounting for the highest part of that, totalling an expenditure of TL 41.6 billion (US$ 1.3 billion) in 2023.

They argue, however, that “it’s essential to remember that providing these medications to patients at no cost is a responsibility of the state, aligning with the principle of a social welfare state.”

Limitations of legal action

The success of these actions can come at a price, however, as the story of a son’s efforts to secure reimbursement for a cancer drug prescribed for his mother demonstrates.

Umut Ak comes from Samsun, the largest city of the Black Sea Region. When his mother was diagnosed with lung cancer, genomic tests indicated that she could benefit from pembrolizumab, and the drug was prescribed accordingly by her oncologist.

As the drug was not on the SGK list, the family could only access the drug if they paid the whole cost from their own pocket, which they were unable to do. While in 2023, two boxes would have cost TL 80,000 (US$ 2,500). Thanks to the high inflation and deteriorating exchange rate, by March 2024 that cost had increased to TL 140,000 (almost US$ 4,500).

They decided to take the legal route, to force the SGK to reimburse them. But the process was complex and lengthy, and his mother’s health was steadily deteriorating. By the time they won their case, it was too late. “It was a very difficult process, finding a lawyer, covering court costs – a total waste of time for a cancer patient,” says Ak.

Disappearing drugs

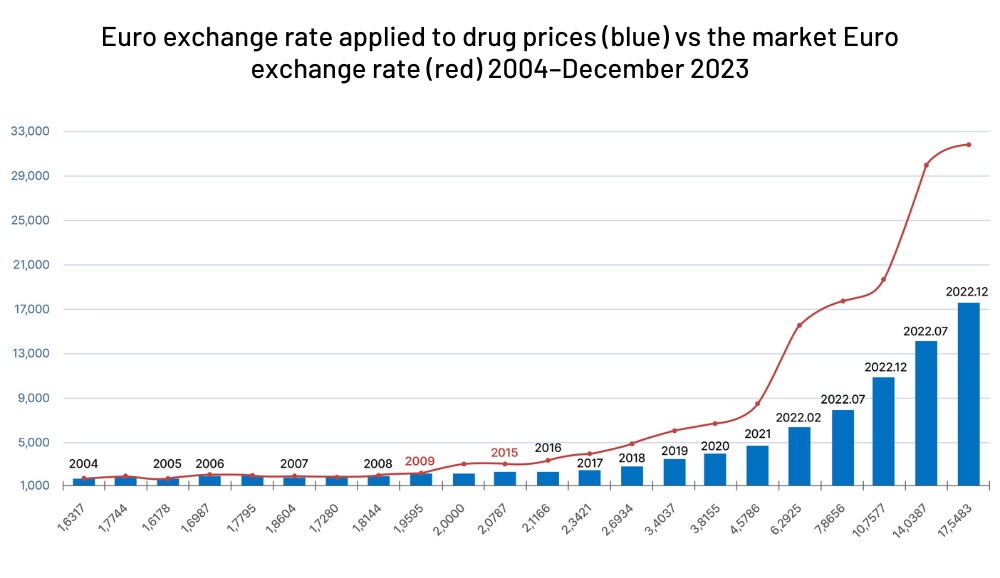

The access problem extends well beyond drugs not currently on the SGK list for reimbursement, says Özcan. The Turkish Ministry of Health determines a fixed Euro exchange rate, under the Drug Pricing Decree (İFK), when pricing reimbursed medicines every year, which they calculate on a fixed exchange rate. That exchange rate has been diverging markedly from the market rate over recent years, meaning that the euro price received by the pharmaceutical companies has been markedly reduced.

As a consequence, companies have started withdrawing drugs from the Turkish market. In August 2023, Roche decided to cease supplying a critical drug used in post-organ transplant care. In December, Novartis announced it would be halting distribution of 14 drugs including drugs for managing severe conditions such as epilepsy. Some of those drugs have no equivalents in the Turkish market, says Özcan, while others do exist but are rare and difficult to obtain.

“The devaluation of drug prices in the face of inflation leads to economic challenges for pharmacists, distributors, and manufacturers alike,” she says, “Furthermore, the scarcity of drugs in the market results in considerable hardship for patients.” Current pricing and purchase arrangements need urgent updating to reflect the huge drop in the value of the Turkish lira, she says, “The Euro exchange rate set by the İFK, and many other articles in the same decree have lost their validity,” Özcan argues. “Given the current circumstances, it is urgently necessary to update the İFK to reflect the new economic conditions.”

How Turkey’s currency crisis is impacting on drugs prices and availability

The exchange rate set by Turkey for purchasing drugs, under the Drugs Pricing Decree, is currently fixed at 1 Euro=17.6 TL. However, due to the currency crisis, the actual exchange rate, as of 7 May 2024, is 1 Euro= 34.7 TL. The difference is resulting in many drugs being withdrawn from the Turkish market. Drugs not on the reimbursement list, which include some important cancer drugs, do not have their prices regulated by the Government, but the drop in the value of the lira means that their already high prices has effectively tripled in recent years.

The chart shows the significant increase in the gap between the actual exchange rate of the Euro and the fixed rate set by the Drug Pricing Decree over time, particularly notable from around 2018 onwards, with sharp rises in 2022 and 2023.