When I started my fellowship in Italy, I knew I would meet Professor Andrea Ferrari, the Legend whose work I had studied line by line. I thought I was prepared. I had read his papers…

But nothing in the literature prepared me for the person behind the Legend.

There are days in your career that you never forget. For me, one of those days was a Wednesday.

I walked into Progetto Giovani for the first time, still trying to find my own footing in oncology, still convinced that serious work was conducted in meeting rooms, protocols, and labs.

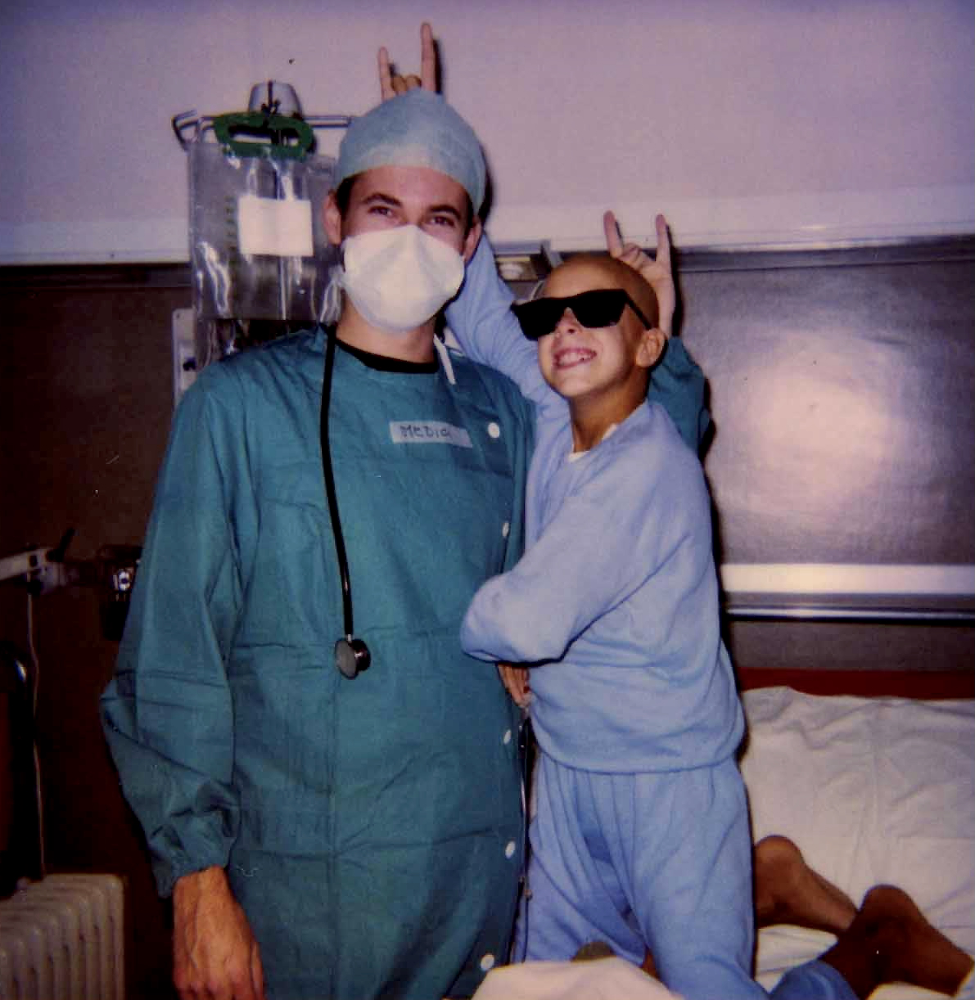

I saw a group of adolescents laughing loudly at something he had said, and there he was, sitting cross-legged in the middle of them, sleeves rolled up, eyes alive, wearing the kind of smile that fills a room without asking permission.

He wasn’t just a doctor.

He was present.

Nothing prepared me for how profoundly he would shape my understanding of medicine, empathy, and what it means to care for young people with cancer.

How Did the Journey Begin

When Prof. Ferrari talks about the beginning of his career, he repeats, “Often things come almost by chance and then become important.”

He grew up inside the San Raffaele Hospital, following his father, a cardiologist, one of the hospital’s first doctors, and a highly respected figure.

Prof. Ferrari remembers him with warmth: “I was full of pride for what my dad was doing. When I was little, we always went to San Raffaele’s parties, to San Raffaele’s retreats. It was a bit predestined, even though I always wanted to write”.

He completed all six years of medical school at San Raffaele Hospital and had already imagined the next decades of his life there. That was the plan he had built.

He says clearly: “I certainly didn’t want to be a pediatric oncologist.”

During his oncology fellowship, he had to complete a mandatory rotation in the pediatric oncology unit.

He says, “That was the 1st of September 1994, a precise date, when I first entered into pediatric oncology unit, directed by Dr. Fossati Bellani. I didn’t want to go there, and Professor Rugarli told me, ‘Look, it is only six months, do the specialty, then come back.”

When he arrived, things changed quickly. “I remember that I fell in love within a couple of days,” he says. “With everything, with the concept of pediatric oncology, with the atmosphere in the department, with the way to interact with the young patients.”

He also remembers his first patient very clearly.

“The first patient they put in my arms was a patient I still see, with a rhabdomyosarcoma, one year old. I always say she is my patient “Number One”, Francesca.

But we were not pediatricians; we were oncologists, so I had never seen a child. It really opened my heart to think of children with cancer.”

What began as a six-month requirement became the field he chose for the rest of his life.

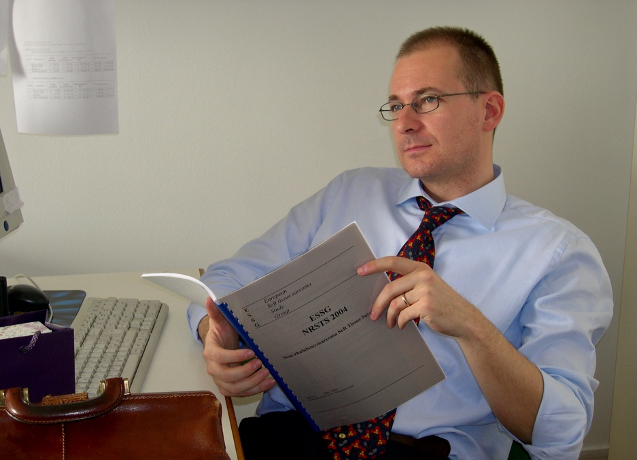

Early Leadership: Histology by Histology

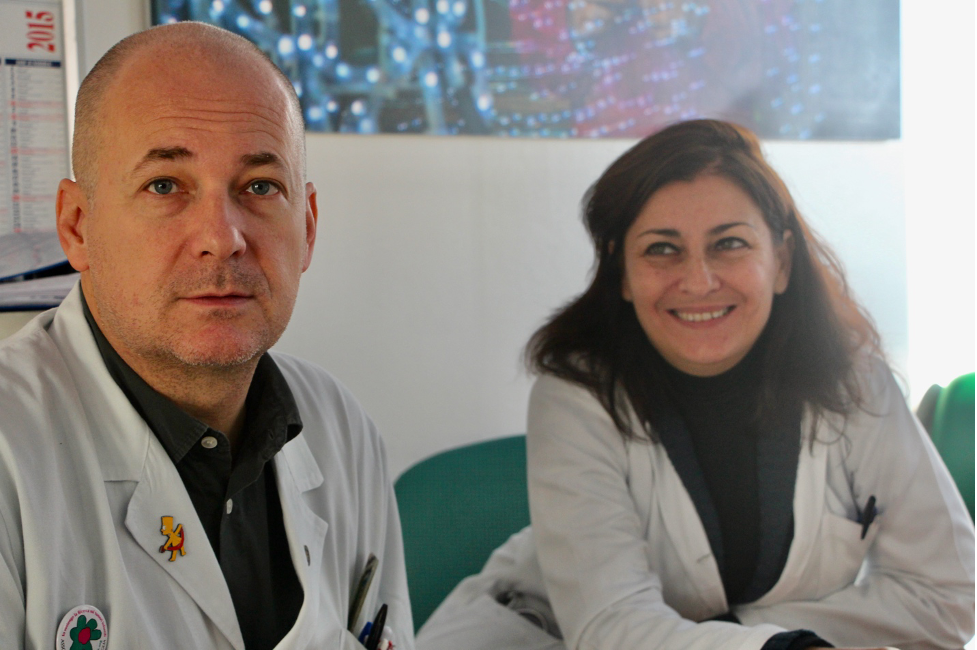

Prof. Ferrari describes the late 90s as a turning point not only for his career, but for European pediatric sarcoma as a whole. He was in his early thirties when he and Dr. Michela Casanova were invited into what would become the core group of the European soft tissue sarcoma protocols. This was the moment when the Italian, German, British, and French groups first joined forces. Few doctors had the opportunity to sit at that table. Ferrari and Casanova did, because by then they had already produced a volume of work that was unusual for their age.

As he recalls: “We were 30 years old, and we were in the group writing the new generation of European protocols. We found ourselves in the founding group of the European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group (EpSSG), together with sarcoma superstar Mike Stevens, Modesto Carli, and Odile Oberlin. And we were 30 years old… in a world of the very first line.”

At the time, sarcomas were often treated as a uniform group, without distinction, following the standard approach adopted for rhabdomyosarcoma, the typical pediatric histotype. The lack of literature served as the starting point for their work.

As he recalls: “Michela and I started to analyze our center’s series, spending hours, often during the weekend, in reviewing charts. When I started writing, I reviewed everything available. There was nothing, except for papers published five years earlier by Alberto Pappo for each tumour type. We studied Pappo’s papers and learned from them.”

He continues: “So we began producing these publications, fifteen papers in three years, and now, I have reached 600 papers.”

Their publications, each dedicated to a specific histology, challenged the prevailing approach and formed the groundwork for separating soft tissue sarcomas by biology rather than treating them as a single category. He describes the process with characteristic modesty.

This scientific enthusiasm, achieved while both were still very young, placed Ferrari and Casanova at the centre of the emerging European sarcoma network. Their data and their insistence on biological distinction supported the shift away from managing all Non-Rhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcomas (NRSTS) “like Rhabdo.” This became a defining conceptual change in the early European protocols.

Then he continues, “This incredible thing of maintenance was born… scientifically, it was the most important idea, it was born at our house by Michela and me.”

He explains: “At the end of the ’90s, we started using vinorelbine in relapsed rhabdomyosarcoma. No one in the world was doing that. There was just an abstract from a Brazilian colleague with a few cases. We started with a case series of fifteen patients showing the efficacy of vinorelbine.”

When the European group convened, the issue was raised again, not as a polished proposal but as a practical question from two young clinicians who had observed something promising.

“We brought this idea as thirty-year-olds into the European group, and we were fortunate with Prof. Carli, Mike Stevens, and Odile Oberlin — senior people, but very intelligent.

The pivotal moment came when they had to decide where vinorelbine should fit in the treatment pathway: “We asked ourselves: where do we put it? And that’s when we said, let’s invent a maintenance.”

Maintenance therapy for rhabdomyosarcoma, now recognized as one of the most successful randomized results ever achieved in this disease, was born from that discussion, built on fifteen patients, two young investigators, and a rare environment of scientific openness.

Adolescents and Young Adults: A Different Way of Seeing Patients

When Prof. Ferrari speaks about adolescents and young adults (AYA), his voice changes. Even for someone who has shaped European sarcoma research, he is clear:

“If I think about my work, the biggest mark I have left is in Non-Rhabdos… but the AYA world is the most beautiful thing.”

His involvement in AYA oncology began almost by chance. He recalls attending a tiny 7 a.m. meeting at a SIOP congress in the mid-2000s:

“I didn’t know anyone. I went into a small room with maybe six or seven people. And there I met Ronnie Barr and Archie Bleyer.” He refers to them as mentors. “They were presenting early data showing worse outcomes for AYA compared with children, something very few had paid attention to.”

“The term ‘AYA’ didn’t exist. There were many publications on children, almost none on adolescents and young adults.”

That meeting opened a door. By 2007, Ferrari had organized the first Italian meeting on AYA, inviting Ronnie Barr and Archie Bleyer. What started as discussions on clinical trial access soon became something much bigger.

The Birth of Youth Project

Together with psychologist (and his great friend) Carlo Clerici, Prof. Ferrari began imagining a different kind of space for adolescents in oncology — a space that was not only medical.

It started almost playfully: “At the beginning, we wanted something colorful, something fun, something that could attract attention. If I tell a journalist that adolescents have a 46% survival rate instead of 65%, no one listens. If instead you make a Christmas song that gets 20 million views, people listen.”

What began as a creative idea soon turned into a structured program, Youth Project — a place where adolescents could meet, create, and share their experiences. The aim was simple but revolutionary:

“To use their words, their smiles, their eyes to send messages.”

Prof. Ferrari remembers that they were lucky because they immediately had the support of the Pediatric Oncology Unit director, Dr. Maura Massimino, and of the charity Associazione Bianca Garavaglia, who made new ideas their own.

The weekly Youth Project meeting on Wednesdays became the center of Prof. Ferrari’s work:

“You can take away everything else, but not Wednesday.” He describes his commitment as almost protective: “I have a great sense of protection toward these young people.”

What is the success?

“The atmosphere is the key. When you enter, everyone is on the same level, adults and adolescents. They know they are listened to.”

And the second reason: “Because there is a doctor who does this as his main commitment, not as a hobby. In other places, someone gives five percent of their time. I do the Progetto Giovani as my main work.”

This doctor-led model gives adolescents something rare: “They see you as a person, not only as a doctor — with dreams, family, football, travel. You sit on the floor with them, joke with them, and take their hands. Protocols are essential, but they are not enough.”

Over the years, the Youth Project grew into a creative laboratory: music videos, photography, writing workshops, even an original sitcom.

Prof. Ferrari says: “Every year we discover what the adolescents can do, and every year we create something better. We learn from them. We walk together, from the

development of artistic laboratories to the publication of the projects in scientific journals.”

The project is now recognized internationally and has become a model for other institutions. Still, he returns to what matters most: the adolescents, the atmosphere, the simple human contact that defines the project.

“Every Wednesday is a story. Just as we say, we don’t want to treat a patient; we want to treat a person.”

The Place and The People

When Prof. Ferrari looks back at what shaped his career, he says, “What influenced me most was the place where I worked. Not just a hospital, but The INSTITUTE — in the strongest sense of the word. The training, the atmosphere, the environment were vital, beyond any single person.”

He adds: “All the colleagues I found, even those with whom I argued, left a mark. Of course, I must recognize the two chiefs of units, Dr. Franca Fossati-Bellani and Dr. Maura Massimino. They formed what you become.”

He remembers a decisive moment with Mike Stevens. When the EpSSG needed a coordinator for the NRSTS 2005 protocol, choosing an Italian was politically difficult because Dr. Bisogno had already been indicated for the rhabdomysarcoma protocol. Nevertheless, Mike Stevens insisted, “No, we’re not discussing this. Even if he is 35 years old, Andrea does it.” That support allowed him to take on responsibility very early.

Speaking about Alberto Pappo, he says, “Even without having met Alberto Pappo, in my first years I considered him as sort of a mentor.” When they eventually met in the United States, the exchange became a defining moment:

“I told him, ‘In Italy, my wife calls me the Alberto Pappo of Italy.’ And he said, ‘That is incredible. Do you know what my wife calls me? She calls me the Andrea Ferrari of the United States.’” Prof. Ferrari adds, “I laughed for an hour. I loved him immediately — not because it was true, but because he was so generous.”

He mentions Carlos Rodríguez-Galindo: “We met by chance at a congress in Guatemala. We became friends, spending nights talking, not about work, but about books, films, life.”

He also talks about friendships that came naturally over the

years: “Our scientific career is a long trip, and along the way you find friends.”

He speaks warmly about Daniel Orbach: “Another very good friend of mine.”

About Gianni Bisogno, he says: “I’ve probably argued more with Gianni than with anyone else. But I truly respect him. We did everything together. He is like your twin, the one you fight with, but he is someone you’ve trained a lot with.”

If he needs to think about a special person in his hospital, he thinks about Stefano Chiaravalli: “With Stefano, there is harmony in everything. His passion for the clinic allowed me to take a little less care of the clinic and more of the science.”

In the end, his message is simple: oncology careers are shaped by places, by people, and by years of shared work. No one builds anything alone.

The Chapter Not Written in Protocols

Prof. Ferrari has a lot of hobbies. But he explains them in his own way: for him, the things he shares with adolescents are simple and human: traveling, football, books, and writing. They are the parts of his life that help them see him as a person

“In my opinion, hobbies exist to create a compartment where work doesn’t enter, even when you love your work so much that it could fill everything. It’s not about escaping something you dislike; it’s about protecting space for the rest of your life.”

He explains that oncology is very invasive — “in a good way,” — and that every doctor needs a space untouched by the hospital. For him, that space became very structured.

This is why long intercontinental trips became essential: “For two weeks, nobody writes emails, nobody asks about cases. You are far away, and the world does not enter.

He quotes Bruce Chatwin’s concept of distance, the concept of being far enough that your mind breathes differently. Not as an escape from something unpleasant, but as a way to protect passion from burning out.

To keep his worlds separated, he even created a pseudonym years ago:

“Gaetano Pappuini was born to give me a space where I could put other things.”

It helped him balance life at home as well. He and his wife are both pediatric oncologists, two people fully immersed in the same demanding field: “We couldn’t go home and talk about patients or protocols after dinner.”

Gaetano Pappuini became the door he could close when medicine needed to stay outside for a while.

One of his passions is writing.

The scientific book about Adolescents and Young adults with cancer by Andrea Ferrari and Fedro Peccatori. The story of his first novel book began almost by accident. He tells it with a kind of amused affection.

“It was ten years ago, I had two aunts in their nineties. Every Saturday, I went to visit them. They only asked about pain and medicine. He tried to keep the conversations alive.

“One day I told them, ‘Tell me about the past.’” continues “I opened closets full of incredible documents, the testament of my grandfather, a prison diary from the First World War, photographs from the 1800s… an unbelievable amount of material.”

He gathered everything and created a large book for the family: “I simply photographed everything and added short captions.”

Years later, during COVID, the book took a different turn. That strange combination of lockdown, insomnia, and a pile of family notes pushed him back to the book.

“I don’t even remember how it happened… I started transforming all those notes into a novel.” At the beginning, he didn’t plan to publish it. It was something private, something he did for himself. But now the book is published, with the title “Wars are always lost”, and is having a good success in Italy.

Michela Casanova

Prof. Ferrari says: “We both had our own stories. It wasn’t that we fell in love immediately. But from the very first weeks working together, we created a professional feeling that was really unique.”

He describes the early period as intense, shaped by exhausting shifts and constant responsibility

“In those years, the department had many changes. We were very young, doing shifts of 24 consecutive hours. They were very heavy. When Michela was on shift, I went to help her. When I was on shift, she came to help me.”

One night, he says, remains the symbol of how their bond formed.

“There was this boy, Claudio. We were both there at night, giving morphine, sedatives, trying to let him sleep. He weighed 100 kilos. We were desperate, but also moved. These experiences shape you. These stories and these bonds are the strongest part of everything, even the difficulties.”

He is direct about how challenging it is for two oncologists in the same field to stay balanced. “It’s not easy. You deal with the same things. You risk internal competition. And there is the danger that one becomes strong and the other becomes subordinate.”

“But that did not happen. It has never been like that. Not for a second. I think we were very good at this. And certainly love helped us. She and our son Pietro are the deepest meaning of my life.”

The Passion

When asked what he tells young doctors, he answers immediately: “Passion.”

“I think the strongest message I try to give is the passion for your work,” he says. “Medicine, not only oncology, is a job of passion. You can’t be a doctor without passion.”

He often reminds students of the energy they had at the beginning: “I remember the face we all had when we graduated. We couldn’t wait to enter the world. That was the passion you had at 25.”

“In this job, you risk losing the flame. The work is tiring, difficult. Administrative things wear you down. Disappointments wear you down. Expectations wear you

down.”

The challenge, he says, is not starting with passion; it’s keeping it.

The Journey

Prof. Ferrari is clear-eyed about the stage he is in.

He has just begun his university appointment and finds real joy in teaching.

“I like teaching a lot. Dedicating myself to young people, I care about that deeply.”

At the same time, he carries two enormous responsibilities: the EpSSG, where he will become Board Chair. “I would like to take a step back from the heavy scientific work

and offer more vision, governance, relationships, the direction of things, AND Network of Expertise (NoE) on AYA developed within the Joint Action JANE, which he co-coordinates. “It takes a huge amount of time. It’s policy work, but it is very important.”

He never complains about the clinic; in fact, the opposite.

“I would never give up my clinic. People say the outpatient work is tiring…But I would never want to lose it.”.

His message is simple, and he quotes Calvino to make it clear:

“The greatest fortune a person can have is to find a work that you truly love.”

From the Author

I have read every protocol and paper he ever wrote.

But the most important thing he taught me isn’t written anywhere.

It is the way he treats young people as whole human beings.

The way he protects Wednesday like something sacred.

The way he keeps passion alive when the work becomes heavy.

As his mentee, that is the chapter I carry with me the one not written in the protocol, but written directly into my heart.