Jayasree K. Iyer doesn’t pause when asked what keeps her awake at night. “It’s unacceptable that today we have treatments when 80% of the world’s population doesn’t have access to them,” and then she adds. “Why are we celebrating progress in development and stopping there?”

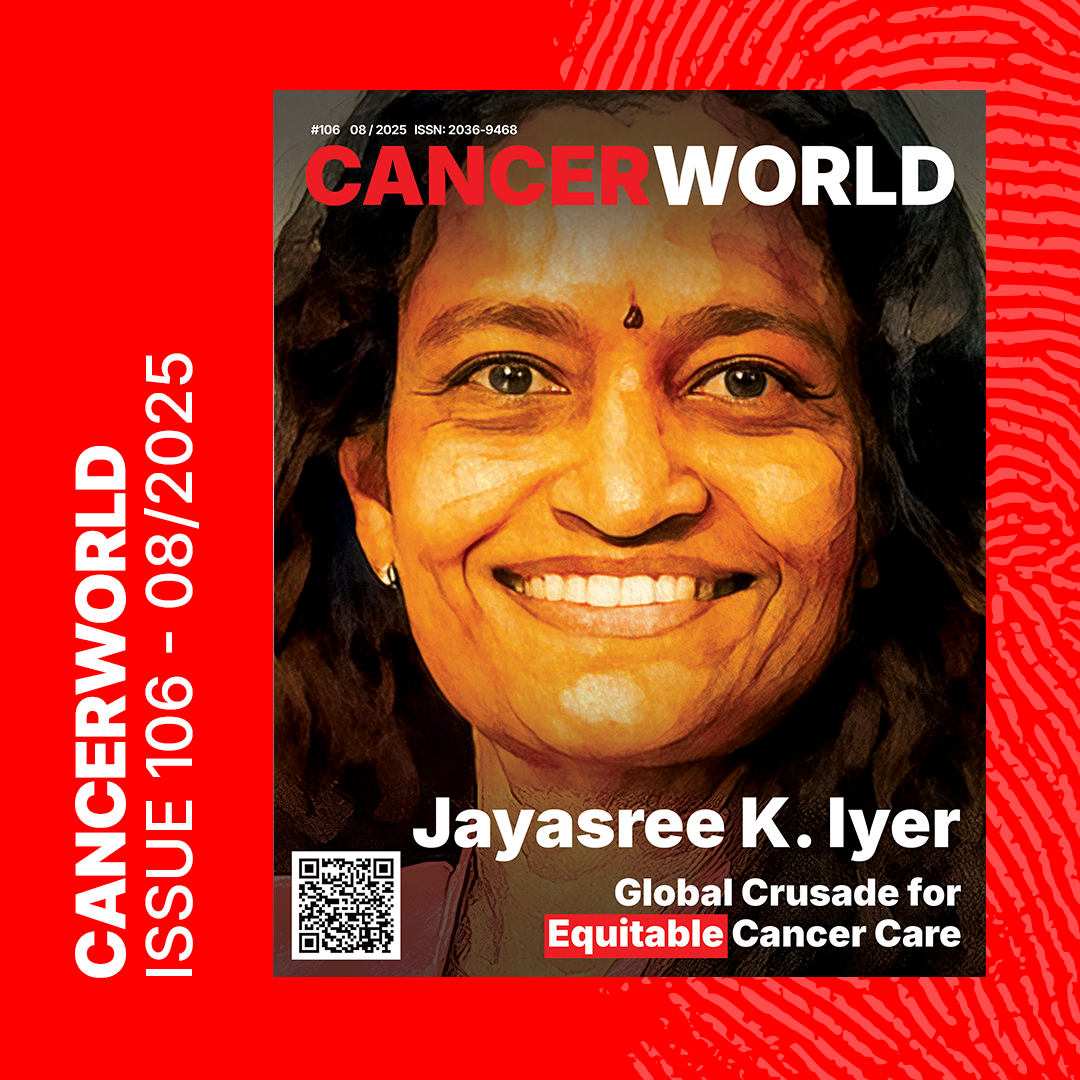

This is not rhetoric. As CEO of the Access to Medicine Foundation, Iyer is at the helm of a quiet revolution, one that targets the pharmaceutical industry’s uncomfortable blind spot: the vast chasm between medical innovation and who actually receives it.

In this profile article, CancerWorld will take you into a conversation that pivots effortlessly from Iyer’s childhood in Singapore’s hospital corridors to systemic failures in global cancer access.

A story and a fight for equity.

Early Roots: Hospital Walls and Unseen Worlds

Born and raised in Singapore in the 1970s, Iyer’s early life unfolded inside the walls of a hospital campus, where her father worked as an anesthesiologist. “We lived right there,” she recalls. “I basically grew up running in and out of a hospital until I was in my teenage years.”

This setting gave her a front-row seat to the practice of medicine, and to its limits. “Singapore was developing then. And it’s a very multicultural country,” she explains. “People had very different understandings of what ‘medicine’ meant. Traditional Chinese medicine, Malay herbs, Indian home remedies, they were all part of the patient’s journey.”

Even in a modernizing city, many clung to belief systems that diverged from Western models. “You’d have someone with a tumor see a traditional healer, not realizing they needed a surgical intervention. Meanwhile, cancer was a death sentence back then. Nobody even talked about pathology.”

That contrast between what medicine could offer and what people received etched itself into Iyer’s conscience. Her experiences weren’t limited to clinical encounters. Her family stood out as a rare Indian household in Singapore at the time, isolated from most relatives who remained in India. “It’s a twist of fate,” she says. “We were the only ones who lived abroad. And you realize that access to care is not about merit or need, it’s about geography, economics, and sometimes gender or sexual identity.”

These early impressions would later evolve into a global perspective shaped by academic rigor and professional conviction.

The Dinner Table Diagnosis: A Family Immersed in Oncology

To understand Iyer’s stamina, you need to understand her world. Her brother is a head and neck surgeon. Her sister-in-law, a radiation oncologist. Her husband, also an oncologist. Even her father, back in Singapore, used to narrate his day’s surgical cases at the dinner table.

“Cancer was always there, not in a tragic way, but as a constant part of conversation. As a child, I’d see patients being wheeled out. Sometimes I’d deliver food to the OR. It wasn’t dramatic. It was just daily life.”

Access to care wasn’t an abstraction. “Every conversation was about what wasn’t available, what treatments someone couldn’t get. Or what someone had to give up to afford care. It was always around us.”

The Science of Strategy: From Pathogens to Policy

Years later, Iyer trained as an infectious disease scientist, captivated by the intellect of microorganisms. “Pathogens are incredibly smart,” she says. “They replicate, evolve, survive. They use the host’s own biology to keep going. That fascinated me.”

Her voice lifts slightly as she makes a surprising parallel. “Cancer is the same. It’s a highly intelligent disease. The difference is that it spreads internally, not from person to person. But it’s just as tactical, and just as devastating.”

The insight that cancer and infectious disease both manipulate biology, both evolve with uncanny precision, gave Iyer a long-range view of what it means to fight disease. “And yet, in both cases, prevention matters. You can often stop both early, but only if people know what to look for, and can afford the care.”

then President of the whole Johns Hopkins University, William Brody

She studied at Johns Hopkins, where a mentor once led her through the ICU. “We stopped in front of a nun in a coma with cerebral malaria. Then, a woman with metastatic cancer. He asked me to think: how could we have prevented this?” she recalls. “I was taking notes furiously, but also thinking, this is what I grew up seeing every day.”

That moment sharpened her resolve. “I realized I didn’t want to just identify disease. I wanted to fix the systems that failed people.”

Her academic background taught her how resilient disease mechanisms are. But her real-life experiences taught her that inequity, not biology, is often the bigger killer.

The Weight Doctors Carry, and Why It Must Change

Iyer emphasizes the compounding pressures faced by clinicians around the world. “Doctors aren’t just responsible for diagnosis and treatment anymore,” she says. “They also have to be educators, cultural translators, and financial negotiators.”

She explains that many patients approach disease through the lens of traditional healing, misinformation, or social stigmas. “It’s advising patients and caregivers about lifestyle choices,” she says. “A lifestyle where they’re used to traditional medicines, or to smoking, or to someone telling them something about a disease that they think is the absolute truth.”

Add to that the complexity of cultural sensitivity and limited medical infrastructure, and it becomes overwhelming. “A medical doctor has to have a lot of knowledge of how to treat a disease, and on top of that, be compassionate to sort out the different cultural differences that people have,” she says. “And now, on top of that, they’re also supposed to talk about price and affordability, because they cannot prescribe things that people are unable to pay for.”

That final burden, access, cuts deepest. “Access to medicine is more important now than ever before,” she concludes. “We are asking too much of our doctors while doing too little to fix the systems around them.”

A Broken System

Last year, the Access to Medicine Foundation hosted 40 patient advocates from around the world. The message was depressingly uniform: unaffordable drugs, unregistered medicines, forced travel to neighboring countries, reliance on black markets, and late-stage diagnoses.

“The fact that I heard the same stories from 50 countries… It was heartbreaking. But also clarifying. The system is broken at a structural level.”

She’s especially critical of the industry’s over-reliance on organizations like the Max Foundation, which distributes free drugs to low-income patients.

“The Max Foundation does incredible work. But free drugs for a few people can’t be our solution. We can’t pat ourselves on the back for that while the rest of the world waits.”

Her voice is firm: “Charity is not scale. Compassion must be designed into systems, not outsourced to goodwill.”

The Geography of Access and the Irony of Innovation

Across the conversation, one truth keeps surfacing: the pharmaceutical industry’s progress means little if its products stay locked behind paywalls or national borders.

“It’s tragic. We have treatments. We have science. But the average patient in a low-income country will never see those drugs. Geography has become a death sentence.”

She describes hearing from patients who cross borders, drain their savings, or turn to informal black-market channels just to stay alive. “Some make it, most don’t. That is not a functioning system. That’s global negligence.”

Even clinical trials, often a backdoor to advanced care, remain confined to high-income nations. “If trials aren’t diverse, if access to innovation is unequal, how can we ever claim success?”

Access to Medicine Foundation’s Work and Impact

Under Iyer’s leadership, the Access to Medicine Foundation has grown into a globally influential force that holds pharmaceutical companies accountable, not just for what they invent, but for whom those inventions serve.

The Foundation produces rigorous, public-facing research on how the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies perform when it comes to ensuring people in low- and middle-income countries can access essential medicines. Their most recognized outputs include the Access to Medicine Index, the Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Benchmark, and the Access to Oncology Medicines report, each of which critically assesses industry behavior and spotlights best practices.

Their work spans a wide range of diseases, both communicable and noncommunicable. This includes cancer, diabetes, hypertension, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, maternal health, childhood vaccines, and neglected tropical diseases. More recently, the Foundation has also explored access barriers in areas like mental health and emerging infectious diseases.

“We don’t just point fingers,” Iyer explains. “We track where change is happening, highlight what’s working, and push for collaboration between companies, regulators, governments, and local health systems.”

The Foundation’s impact is both practical and political. Their data have been used by procurement agencies and funders, from Gavi to the Global Fund, and even by governments reshaping their national strategies.

One of the organization’s key initiatives is spotlighting which companies are registering drugs in low- and middle-income countries and where the gaps remain. Another is mapping where local manufacturing or supply chain resilience can be strengthened, especially in light of COVID-era disruptions.

“Access can’t be a side project. It must be embedded in the business model,” Iyer insists. “We’ve seen companies do it well when they have clear leadership, local partnerships, and the will to act. The blueprint exists. It’s a matter of scaling it.”

As global health conversations shift post-pandemic, Iyer wants to see the industry move beyond charity and toward accountability. “Free drugs for a few is not a solution. It’s a stopgap. We need systems built on justice, not generosity.”

Advocate, Not Activist

When asked if she considers herself an activist, Iyer demurs. “I’m not an activist. I’m an advocate,” she says. “I use evidence to push for change. But at some point, we need activists too. Because we’re not doing enough.”

The difference is more than semantic. Where activism demands, advocacy negotiates. And Iyer, with her command of data and fluency in diplomacy, understands the language of both pharma executives and disillusioned patients.

“Whether it’s HIV, cervical cancer, or leukemia, access is still dictated by geography, income, gender, and even sexual orientation. That’s not just a medical issue. That’s a moral failure.”

Her mission is clear. “I’m not here to shame. I’m here to solve.”

What’s Next?

She believes the pharmaceutical industry can do better, because she’s seen glimpses of it. “There are models that work. But they need to be replicated, scaled, incentivized. The whole reward system needs rethinking.”

More cross-border regulatory alignment. More local manufacturing incentives. Better licensing terms. Lower entry barriers for generics. Universal pricing transparency. These aren’t dreams, they’re policy blueprints.

What gives her hope are the people: the policy-makers who listen, the regulators who adapt, and most of all, the patients who persist.

“To the patients who feel ignored: you’re not alone. Your voice matters. Don’t stay silent. That’s how we break the system.”

In Jayasree Iyer, the global health community has more than a watchdog. It has a strategist. A bridge-builder. And yes, a crusader, one who doesn’t raise her voice, but raises the stakes.

And perhaps that’s what makes her unstoppable.