“I had very severe symptoms. I had jaundice, I had itching – symptoms that could definitely indicate something related to the liver, or quite severe disease – but because of my age I was repeatedly just shoved away.”

(Gabriel, eventually diagnosed aged 21 with biliary tract cancer with liver metastases)

“It came as a surprise in the middle of the neoadjuvant treatment that I realised I am starting to experience something like menopausal symptoms. I went to my radiation oncologist to talk about it, and she honestly admitted that she forgot to tell me about it, because she wasn’t used to treating young patients.”

(Lasma, diagnosed aged 33 with stage 3 rectal cancer)

“When you are diagnosed at a young age, every part of your life changes completely. You have to stop working, finances are affected, fertility is affected, the daily routine, even sense of identity is so complex. There is a whole process of grieving the life you have lost, that you need to go through. And it is a long process.”

(Natalia, diagnosed aged 23 with stage 4 gastric cancer)

Testimonies from patients took centre stage in discussions at ENTERO, a conference organised by Digestive Cancers Europe that asked why this group of cancers has been on the increase among younger people since the mid-1990s, and how to reverse the trend and improve the care and outcomes of patients and survivors.

The stark fact at the heart of the conference is this one: the incidence of digestive cancers in adults under 50 years old has surged by almost 80% over the past 30 years. And while a small part of this increase can be explained by changes in known risk factors, such as obesity, most of it remains unexplained. Intriguing differences in rates and trends between genders and between countries offer a way in to explore what could be driving the uptick in new cases, using a combination of powerful new tools.

But as the patient testimonies made clear, the knowledge and tools already available at a clinical level are still not being used effectively, resulting in late diagnosis, inadequate information and involvement in decisions regarding treatment options, and a failure to support patients’ quality of life at both a physical and mental level. Having their voices at the centre of every session kept the scientific and clinical discussions firmly rooted in realities.

It also gave a purpose to the conference beyond ‘academic discussions’. Changing things for the better – at the levels of prevention, early detection, treatment, care and survivorship support – requires advocacy, and the patient advocates in the room, and the thousands of others they work with, will be crucial to pushing for change in their own health systems.

Annual percent change in age-specific colorectal cancer incidence rates in Europe, 1990–2016

Source: Vuik FE, Nieuwenburg SA, Bardou M et al. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in young adults in Europe over the last 25 years. Gut 2019;68:1820–26 (top section of figure 2)

© Vuik FE, Nieuwenburg SA, Bardou M et al. 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY 4.0. Published by BMJ

What’s going on? Investigating the causes

Prevention is better than a cure. However, it is hard to prevent what you don’t understand. And the risk factors behind colorectal and other digestive cancers, at any age and specifically among early onset cases, remain elusive. Among the patient advocates in the room was at least one whose early-onset cancer was associated with Lynch syndrome – one among a number of genetic conditions that can raise the risk of digestive cancers. Others reported that their dietary and exercise patterns could have made their diagnosis more likely. But many reported exemplary lifestyles – no smoking, no drinking, good diet and plenty of exercise – and said no known genetic risk factors had been identified in their diagnostic work up.

This latter group, with no known risk factors to explain their diagnosis, constitute the majority of cases. The task of identifying the hidden drivers of their cancers has been taken up by DISCERN, a large EU-funded initiative that is focused specifically on illuminating the causes of colorectal, pancreatic, and renal cancers.

“Of the known risk factors, we can explain about 40% of colorectal cancer cases, maybe a bit less for pancreatic and kidney,” says Marc Gunter, one of the DISCERN coordinators, who introduced the project at the ENTERO conference. “Where is the rest coming from? It’s not genetics. Genetics plays a small role. There must be something else.”

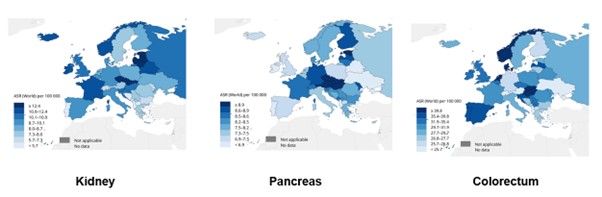

Putting it down purely to chance seems very unlikely, says Gunter, not least because of striking variations in incidence rates across Europe. “For example, kidney cancer – we see a cluster of countries with the highest rates in central and eastern Europe: Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, also some of the Baltic countries have the highest rates of kidney cancer, whereas as other countries have much lower rates. For colorectal cancer, we see the highest rates in Norway, Denmark the Netherlands and also Hungary. That variation might indicate there are some specific environmental factors that could be driving those cancers.”

While DISCERN is not only focused on early-onset digestive cancers, it is looking specifically at this subset, as the rising incidence rates in this age group would seem to indicate something specific is at play. Questions being asked include: Are the risk factors the same for early onset as late onset cases? Do the associations differ in magnitude and/or nature between early and late onset? Are there novel risk factors and susceptibility? Does rising incidence in younger age groups reflect a birth cohort effect?

Heat maps of incidence rates of kidney, pancreas and colorectal cancers across Europe

Source: Courtesy of Marc Gunter, co-coordinator of the DISCERN project (Discovering the Causes of Three Poorly Understood Cancers in Europe)

It will be a while before we start seeing results from DISCERN, as the study has a further three years to run. However, results from other studies using prospective epidemiological data and biobanked samples, such as the Colorectal Cancer Pooling Project (part of the US NCI Cohort Consortium) have already started to throw some light on potential differences in risk factors between early and late onset cancers.

That study found that, while known risk factors for this cancer in the general population play a role in early onset cases as well, their importance may not always be the same. High BMI, for instance, seems to play a stronger role in early onset colon cancer cases, as does larger waist circumference, particularly among men. Smoking and alcohol seem to confer similar levels of raised risk in early as in later onset – though a past history of smoking is a higher risk factor at an older age. Diabetes may be a higher risk factor for early onset rectal cancer.

Metabolic indicators – such as fasting insulin levels, as well as genetically predicted obesity – had a higher association with early onset than late onset colorectal cancers. Genetically predicted alcohol intake also showed a stronger association with early onset cancers, potentially pointing to changes in drinking habits in younger cohorts.

Already known genetic risk factors were confirmed to play the same role in early as in late onset cancers, though they account for a significantly higher proportion of colorectal cancers in younger patients, due to the much lower incidence of sporadic colorectal cancers in this age group. Two new genetic variants were also identified that are specifically associated with early onset colorectal cancer.

The DISCERN study

The DISCERN study uses data from very large population-based studies, such as the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), to look for factors that distinguish those that were diagnosed with colorectal, pancreatic or kidney cancer over the course of the study from those who were not. It also uses existing geospatial data that maps levels of air and water pollution across Europe. The data is then analysed to look for patterns of associations that could point to previously unidentified risk factors linked to dietary or lifestyle factors, or environmental exposures.

Any associations found are then explored in an experimental laboratory setting, using e.g. cell models and organoids, to understand whether the potential risk factors detected in the population-based studies are actually causing cancer, and if so, how?

Combining traditional epidemiology with new techniques such as proteomics and metabolomics to see what is happening at a cellular level, and mass spectroscopy that can screen for thousands of chemicals in blood and proteins, opens up important possibilities to identify risk factors that were previously hidden, says Marc Gunter, co-coordinator of the study, who is based at Imperial College London. “We’ve never been able to do that before. To apply that at a scale that we do in DISCERN, where you have thousands of people and a sufficient number of blood samples taken before the people got the cancer, that is what is really exciting.”

Addressing barriers to early detection

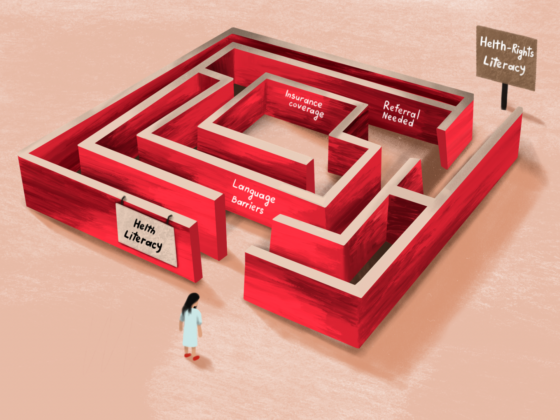

Digestive cancers are notoriously hard to diagnose because many of the symptoms are so similar to other digestive complaints that are much more common. The problem is magnified in younger people, because, while incidence rates have been growing, digestive cancers remain a rare occurrence, so doctors don’t expect to see them – and young people are not aware that they may be at risk. A survey of people diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancers have shown that younger people delay longer before seeking medical attention, and two-thirds of them see two or more physicians prior to the diagnosis. More than 70% of early onset colorectal cancers are diagnosed at stage 3 or 4, which is significantly more than in older populations.

There is also some evidence to show that symptoms of digestive cancers in younger people may differ in some ways from in older populations. In oesophagogastric cancers, for instance, pain and change in bowel habits are significantly more frequent presenting symptoms in younger patients, while weight loss and swallowing difficulty occurred more frequently in the average-age onset group.

The struggle to get to the point of diagnosis was a theme that was common to all the patients’ stories. One survivor of colorectal cancer described visits to her GP over more than a year reporting blood in her stools, which she observed with increasing frequency, to the point that it was present every time she went to the toilet – and still the GP refused to investigate and told her not to worry. A young survivor of cancer of the bile duct talked about having jaundice, with levels of bilirubin that were way above normal, and being wrongly diagnosed with hepatitis and told – despite his denials – that it must have been the result of unprotected sex.

A factor common to all of these stories was a growing certainty on the part of the patients that something was seriously wrong, coupled with a failure on the part of the doctor, over many months and multiple visits, to listen and give credence to their concerns.

A factor common to all of these stories was a growing certainty on the part of the patients that something was seriously wrong

Doctors need to be better at listening to and communicating with their patients, was a point strongly made in the discussion about how to speed up the pathway to diagnosis for this group of patients. Education for GPs was another suggestion, to raise awareness that these cancers can strike at an early age. Also education of citizens, to raise awareness that cancer can strike at a young age, and that they have a right to have their concerns taken seriously, “Even to the point of being demanding. Who cares? It is our life.”

Getting the diagnostic pathways right was also seen as key – guidance on which tests to use to investigate which sets of symptoms and, crucially, easy access to refer patients for those tests. An advocate from Bowel Cancer UK reported on their “Never too young” campaign, which succeeded in getting a change to the UK guidelines about how young people with bowel cancer symptoms should be referred. “GPs must now have access to FIT tests [faecal immunochemical tests] etc. We are seeing a difference.”

A longstanding problem concerning the causes of late diagnosis, which was highlighted in Cancerworld in a 2002 exchange between a GP and oncologist Eric van Cutsem (who later went on to co-found Digestive Cancers Europe), has been the limited options for conducting further diagnostic tests, where the suspicion for cancer is low, but still needs to be ruled out.

Addressing that problem within the colorectal cancer setting is now the focus of the EU-funded OncoSCREEN project, which “will provide… an integrated diagnostic decision support tool for clinicians,” and aims to make available a variety of new non-invasive methods for risk-stratified colorectal cancer screening.

Early detection initiatives for other digestive cancers include the TOGAS initiative, part of the EU4Health programme, which is researching options for screening and prevention programmes for gastric cancer, and the development of the Cytosponge, a simple technique for obtaining biopsy samples to screen for ‘Barrett’s oesophagus’, a condition that indicates raised risk for oesophageal cancer.

The issue of whether the EU should change its guidelines on colorectal cancer screening to start at age 45, in line with the US, was briefly raised. That proposal is not currently on the EU radar, because the incidence in that age group is considered much too low to for the benefits to outweigh the risks. It is worth noting, in this context, that coverage of colorectal screening even among the older population where risk levels are much higher remain very poor across much of Europe.

Getting the right treatment and care

Treatments for digestive cancers can lead to long-term potentially life-changing side effects that impact on one’s daily function, self-identity, sex life and fertility. The good news is that treatments, particularly for colorectal cancers, together with an understanding of how to tailor them to the precise characteristics of each cancer, and the priorities of each patient, have been improving markedly in recent years, leading to longer survival and better long-term quality of life.

A range of targeted drugs including angiogenesis and EGFR inhibitors, as well as immunotherapies, have expanded treatment options. Technological developments in delivering radiotherapy and surgery have reduced the damage to patients. Evidence generated from clinical research offer clinicians and patients important new data to better tailor the aggressiveness of treatment to the level of risk.

A nationwide cohort study, published in JAMA Oncology in 2023, into the survival impact of ending routine use of neoadjuvant radiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer that was not locally advanced, showed that “an absolute 50% reduction in radiotherapy use for nonlocally advanced rectal cancer did not compromise cancer-related outcomes.”

A similar picture is found for omitting routine surgery, in favour of a ‘watch and wait’ approach, in cases of rectal cancer that show a complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation. The approach can avoid long-term functional damage from potentially unnecessary surgery. Regular surveillance is required, because there is a raised risk of local recurrences; however, so long as these are identified early and surgically removed, the survival impact is very small – between 1% and 2%.

Whether that is an acceptable trade-off is something every patient needs to decide for themselves, says Geerard Beets, a surgeon at the Dutch National Cancer Institute who specialises in colorectal surgery. He warns that clinicians can be too ready to make assumptions about patient priorities, especially with younger patients. This is particularly problematic given the evidence that clinicians tend to wrongly assume that patients prioritise cancer outcomes above quality-of-life considerations. That evidence comes from a study done in a general population of rectal cancer patients, and it may be that younger patients do place a higher priority on survival outcomes, he accepts. But it is also true that clinicians are much more inclined to go for more aggressive treatments in younger patients, potentially at the cost of their long-term quality of life. The important thing, Beets stresses, is to always have that conversation, “Don’t assume. Spend time talking and listening.”

These conversations are particularly important, argues Beets, because, while the instinct to opt for the most aggressive treatment may be understandable, particularly among patients diagnosed at a young age, the risk of long-term serious damage can be quite high compared to what is gained in chances of survival.

“Everything was done without me saying ‘yes, let’s do that’. I wasn’t prepared for what was going to happen”

Failure to discuss these things through with patients in advance denies patients their right to be in control of serious and consequential decisions about their own health and wellbeing. It also makes it harder for them to accept the lasting damage that may be done to them, as one patient who was diagnosed with rectal cancer at the age of 33 testified. “Everything was done without me saying ‘yes, let’s do that’. I wasn’t prepared before the treatment for what was going to happen. Everything came as a surprise and most of the things I had to sort out myself,” she said. “Please doctors talk to your patients about these issues. Talk before the treatment. Because [if I’d had that discussion] it would be much easier for me to accept that I will not have children and that I will probably live with LARS [lack of bowel control and/or regularity] for the rest of my life.”

Much can be done to mitigate the impact of treatment, for instance, on fertility, and to help patients manage side effects, for instance through advice on diet and psychosocial support.

Eric van Cutsem, who heads up the Digestive Oncology division at University of Leuven, in Belgium, stressed that patients should only be managed in settings that can care for all the patients’ needs, including on sexual health and fertility, psychological impact, potential toxicities, financial toxicities and survivorship follow-up.

Living with a digestive cancer

Survival, particularly for people just starting out in life, is not so much something to be achieved, as something that requires constant effort. Learning to live with uncertainty and anxiety, developing strategies to overcome the restrictions of limited bowel control, or a stoma, or fatigue, grieving for the person you once were and the life you had planned, finding ways to get back on track, jobs, children, travel, readjusting relationships, and handling unfair obstacles on the way – in access to work, insurance, and mortgages.

These are all areas where patients could do with some help. Several patients mentioned in their testimonies how valuable psychological counselling had been in helping them manage intrusive thoughts and catastrophic expectations, allowing them to focus on the reality of their situation and on aspects of their lives they could control. Several mentioned how important getting the right advice on nutrition and diet had been for their quality of life, or advice on exercise, or on optimising the way they took their medications. Others spoke of advice on rights at work, and on strategies for getting a job after a cancer diagnosis.

In almost every case, however, that help and advice was something the patients had had to seek out for themselves, often enduring severe physical and mental suffering for many months before they found what they needed.

“Survivorship needs to be factored in from the point of diagnosis,” argued Johan de Munter, a specialist cancer nurse and past President of the European Oncology Nursing Society. “Survivorship is about knowing your patient. Who is that person who is sitting before you? What will that person need during treatment? But also afterwards? What will they need to move forward?”

He stressed the importance of well-trained community nurses who can help patients navigate through treatment and survivorship and make sure they do get access to all the types of advice and support they need along the way. Patients shouldn’t have to go out looking for help, he said, “Healthcare should be offering it.”

“Survivorship is about knowing your patient. What will that person need during treatment? What will they need to move forward?”

While not all of that support will be needed up front, psychological counselling does need to be in place from the start, as a key element in the treatment and care plan, argued Luzia Travado, head of psycho-oncology at the Champalimaud Foundation in Lisbon. Reaching the best decision about treatment options requires patients to be receptive to information and able to make complex assessments of pros and cons, which is not going to be possible if the experience of their diagnosis has left them feeling overwhelmed and consumed with fear.

She also pointed to evidence showing that high levels of chronic stress can also have a direct negative effect on cancer outcomes. “Patients who do better can resolve the depression, learn to deal with their anxiety they will have better survival. So it is not a luxury anymore to have psychological support,” she said. She called on ministries of health to put the resources in place to ensure every patient gets access to the psychological support they need, when they need it. “Psychosocial care has always been under the carpet, because it is silent suffering,” said Luzia. “This is a long journey, so patients need to be helped to be prepared to foster their own resources and mechanisms. They need to know how to decrease the catastrophe ways of thinking… One of the things we help patients focus on are what are my solutions, what can I hope for what can I believe in to carry me forward?”

Advocating for a better future

The ENTERO conference was about more than describing current realities and challenges. As indicated by its full title, ‘Enabling New Treatments, Education, Research, and Outreach for early-age onset digestive cancers’, it was about fostering change.

In a final session, speakers from the worlds of European and national policy making and clinical and translational research presented upbeat reports of significant progress, with the Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan, the Cancer Mission, the Health4Europe programme, national cancer plans, and a vibrant European and global research environment.

Ensuring those policies and that research address the needs of all patients, regardless of where they live or what age they may be, will require involving patients and patient advocates and working with them. This was the take-home message delivered by Andi Carlan from Romania, who was diagnosed with stage 3 colon cancer at the age of 36 and, following five years of gruelling treatment, some of it done abroad, is now living with advanced disease.

“As patients we want testing and treatments that fit us like a glove,” he said, “and personalised medicine is offering that – but only if you can actually get it. In Romania and many parts of Europe, not everybody has access to these cutting edge treatments… We need to work together to make sure that every patient, no matter where they are from or what their background is, has equal access to these life-saving treatments and to the best possible care.”

Working together means including the patient voice not just in decisions regarding their own care, but also in decisions that shape policy and research that could have an impact on their care and their outcomes. “One of the things I’ve learnt in this journey is that patients are often left out of the conversation when it comes to research and policy making. That is like being invited to a dinner part but told you can only watch everyone else eat,” he said.

“I believe that patients should have a seat at the table when it comes to clinical trials, research design and policy decision making. After all we are the ones living with the consequences of these decisions. We need to make sure that the treatments being developed reflect our needs and priorities. That means extending the conversation beyond just prolonged survival aiming for the best possible care and quality of life.

“It’s about how we live and what kind of life we want. If patients are part of the process we end up with solutions that work for us.”

16 Stories of courage and resilience

To help shed light on the alarming spread of early-onset colorectal cancer, Digestive Cancers Europe has published an e-book, You’re Young but it might be Cancer, where 16 patients talk of their experiences. The stories unfold across six chapters, reflecting a different part of the patient’s journey. Starting from the unexpected diagnosis and its profound impact on a young individual’s life, the book explores the physical and mental consequences of treatment and how it affects daily life. The young protagonists also share invaluable advice they wish they had received and are now sharing with the public to help those facing similar situations.

Opening illustration shows the faces of some of the patient advocates and others attending the ENTERO conference. Photo credit: Jelena Dragutinovic